The social unrest that characterised the UK of the 1970s perhaps inevitably affected its largest employer, the NHS. The established order in the service was disrupted by a wave of strikes initiated by every echelon of staff, generating reassessment and change.

NHS strikes and the decade of discontent

Cal Flynaverage reading time 7 minutes

- Serial

Industrial action of any kind was rare in the NHS until the early 1970s. But as the new decade dawned, tensions that had been building over a period of years finally came to a head – in tandem with increasing social unrest across the country. A series of strikes affecting every level of the NHS took place. These challenged the assumptions that formed the very basis of the service and prompted re-evaluation of the roles played by support staff, and women more generally.

“It [the NHS] had been a sort of dictatorship of the doctors,” explains historian Jack Saunders, Research Fellow with the People’s History of the NHS project. “Its hierarchical nature – the sense that you shouldn’t question those with expertise – meant that employees hadn’t tended to think in confrontational terms. But anger over pay, and growing unionisation, made people in the NHS become more aware of collective movement.”

Workers in the health service have traditionally been reluctant to withdraw their services, for understandable reasons. Could patients’ lives be put at risk by their actions? Strike organisers therefore had to make careful strategic decisions to mount ethical but effective campaigns – causing logistical or administrative nightmares without interfering with acute and emergency care.

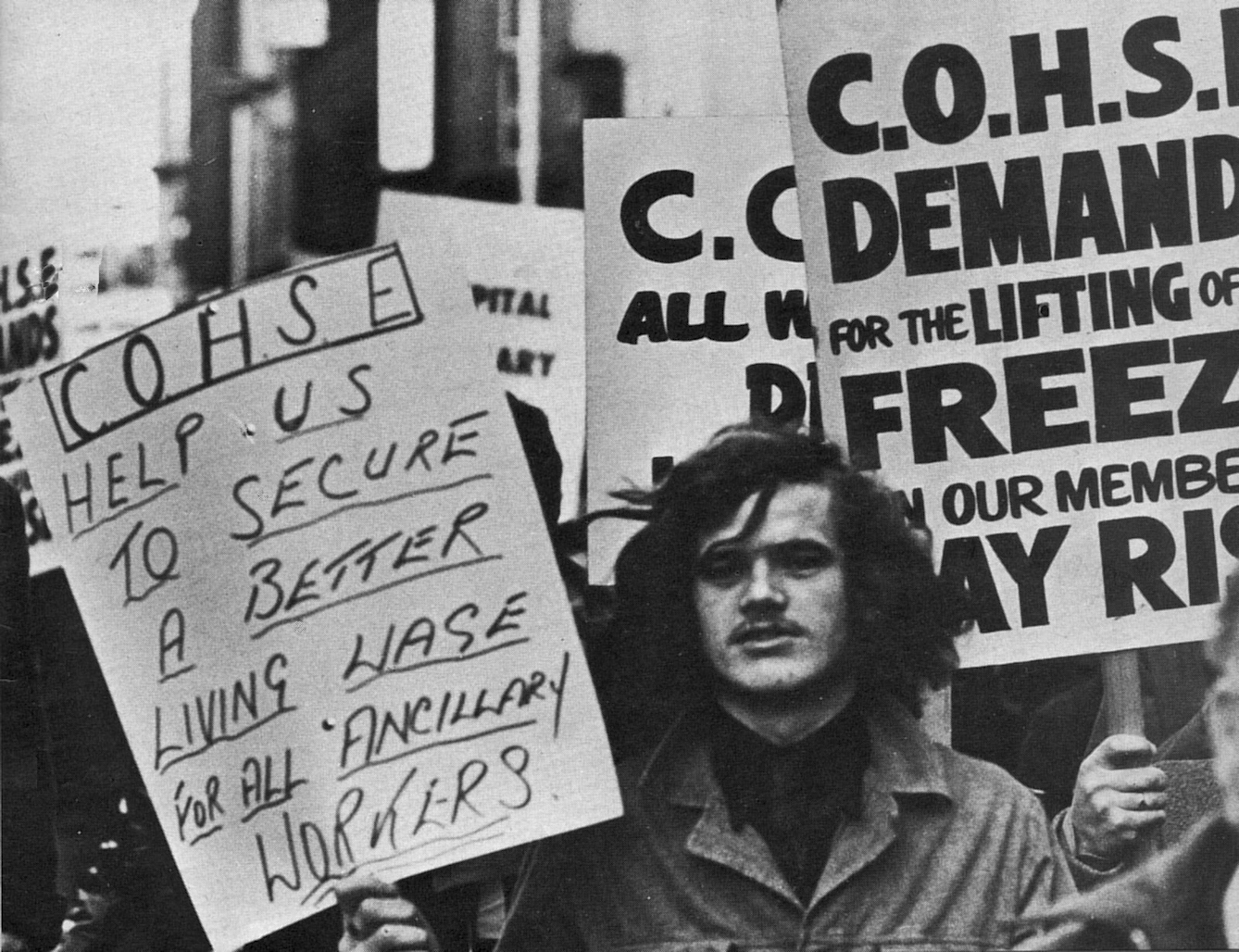

Ancillary workers went on strike after being passed over for a pay rise.

Striking for change, 1973

Of all jobs in the NHS, it was the ancillary roles (porters, laundry workers, catering staff and so on) that were the most poorly remunerated. Successive government reports had found these positions to be among the worst-paid jobs in the country. “The Service has for a long time been able to get by on the goodwill of its employees,” the Department of Employment warned in 1972.

And goodwill was wearing thin. Rising inflation meant already low salaries weren’t going so far. Then when local government staff received a pay rise while NHS workers were passed over, for many it was a bridge too far. Unions agreed a campaign of selective strikes, overtime bans and ‘working to rule’ (doing no more than the minimum specified on their contract), in an action that lasted six weeks and affected 300 hospitals. Although the strikes did not win immediate concessions, they constituted a watershed moment within the NHS. Ancillary workers had proved they were intrinsic to the function of the NHS – and without them, wards and even hospitals would close.

As Jonathan Neale, a hospital porter in London and a steward with the National Union of Public Employees (NUPE), recalled, “The strike itself was no great victory, but it changed the way workers felt. At the end of the strike… The cleaner who hadn’t had a mop in three years got one. The porters got a fridge in their restroom. Now, nobody could be fired out of hand because their face didn’t fit.”

Nurses were next to strike: they received a great deal of sympathy from the public and the pay rise they had requested.

An “awkward kind of strike”, 1974

The decision to strike was a particularly anguished one among nurses, who prided themselves on their values of self-sacrifice, patience and kindness, synonymous with the job since the days of Florence Nightingale.

They were also a very disparate group, divided along the lines of rank, gender and class. Psychiatric nurses, for example, had traditionally been male – assisting in the restraint of difficult patients – and considered themselves manual workers, while elsewhere the position was becoming increasingly professionalised.

State-registered nurses, the most prestigious group, tended to join the Royal College of Nursing, and they were constitutionally barred from striking. But those belonging to other unions were free to do so – and in 1974, they did. “It was an awkward kind of strike,” explains Saunders. “There was a constant dialogue about what nursing was and what sort of knowledge it required. Was it a menial role – a doctor’s handmaiden – or a profession in its own right, with a deep skill base? In a sense it was a debate over how women’s work should be valued.”

The nurses’ calls were sympathetically received by the public: they received a million letters of support, and in 1974 a parliamentary committee awarded pay increases of an average 30 per cent. Later, a new class of specialist nurses would also be introduced, expanding the scope for advancement.

Faces of the NHS: 1970s

Jacynth Ivey began her nursing training in 1978. She was told “Girls like you do very well at State Enrolled Nursing” (meaning black girls), but her father had told her to insist upon State Registered Nursing, and she was glad because “being a State Registered Nurse allowed you to become a Sister, to progress.” She would strongly recommend nursing as a career today. “It's a fantastic career... there are so many options when you've done your nurse training... If you love working with people, if you love justice, fairness, equity, if you love caring for people, it's the right career for you.”

Brian Wilson joined the NHS as a dentist in 1976. For him, the variety of different patients and jobs that he encountered were central to his love of the job. He explained, “If you enjoy the job and have a buzz for your job, and you have a really bloody day, you pick yourself up the next day and you go in... In dentistry, you're only as good as your last patient!” He notes that NHS staff play a key role in shaping the service: “If you don't enjoy it, it's in your hands to change it.”

Professor Dr Shiv Pande had planned to become a cardiothoracic surgeon when he joined the NHS in 1971, but he faced discrimination that blocked this career path for him. He ended up working as a general practitioner, which he strongly recommends as a career path because “no two patients are similar. Every condition is different.” He is proud of his work as Treasurer of the General Medical Council because “a happy staff is a better staff.”

One of the arguments made by striking medics was that healthcare should be valued more than nuclear weapons.

The suspension of goodwill, 1975

The next dispute was very different: as much an internal fight between classes of staff as it was a row with the government. Since the establishment of the health service, consultants had been allowed to maintain a number of private patients on NHS premises – a lucrative source of income and one of the key concessions won from Aneurin Bevan in 1948.

But now the newly empowered nurses and ancillary staff complained that these private patients increased their own workload – without bringing a fair share of the rewards. Workers began to boycott these private patients, including a group at Charing Cross Hospital in London led by the “battling granny”, Esther Brookstone, then Branch Secretary of the NUPE.

The quarrel between consultants and lower-status staff was the latest development in a broader disagreement of principle: should wealthy patients be allowed to jump the queue? The Labour government had pledged the abolishment of these ‘pay beds’, but when health secretary Barbara Castle announced plans to do so she faced stiff resistance, culminating in the consultants suspending all ‘goodwill activities’ between January and April of 1975. The action was called off when Castle relented, allowing part-time consultants to continue private practice; her plan to phase out private beds over a period of years also had only limited success before Margaret Thatcher’s election victory in 1979 brought it to an abrupt end.

What became clear was that senior doctors still kept a very tight hold on the running of the NHS, and they would continue to do so until the 1980s.

The decade of the power-shift

When the doctors returned to work in January 1976, theirs would not be the last strike to take place in the NHS, but it did draw to a close the most conflictual period in the NHS’s history – when the workforce, particularly those in the lower ranks, felt their collective strength for the first time. They, too, questioned the assumption that NHS staff simply would not challenge their employer, reflecting a power shift across the UK as a whole, as workers demanded greater rights than ever before.

In 2016, junior doctors were on strike once more.

Protesting proposed pay cuts, 1975–6

Junior doctors – that is, doctors who were qualified but yet to attain the status of consultant or GP – were in a somewhat less powerful position. Prior to 1975, they worked an average of 85.6 hours a week, during around half of which they were on call. Under new plans, it was proposed that their overtime pay would be cut by two thirds.

In response, junior doctors mounted actions across the country over several months – including strikes and walkouts – until the government found a further £2.3 million to fund the overtime. One of the ringleaders was Dr Wasily Sakalo, who argued that his sister, who had qualified only one year before in Australia, was earning double what he was after seven years: “It made me determined to try to obtain the same work conditions for British doctors,” he said.

His words echoed the doctors’ increasingly international outlook – and raised the possibility of a ‘medical brain drain’, a spectre that would be raised again in 2016, when junior doctors were again on strike.

About the contributors

Cal Flyn

Cal Flyn is a writer and reporter from the Highlands of Scotland. She writes across the British press, including the Guardian, the Sunday Times, the Daily Telegraph, Prospect and New Statesman. Her first book, ‘Thicker Than Water’, was published by William Collins in 2016, and selected by the Times as one of the best books of that year.