The spectrum of homesickness runs from mildly disquieting to seriously debilitating. In the first of six articles exploring the subject, Gail Tolley recalls the unsettling feeling of childhood homesickness and takes a closer look at what the experience actually is.

The complex longing for home

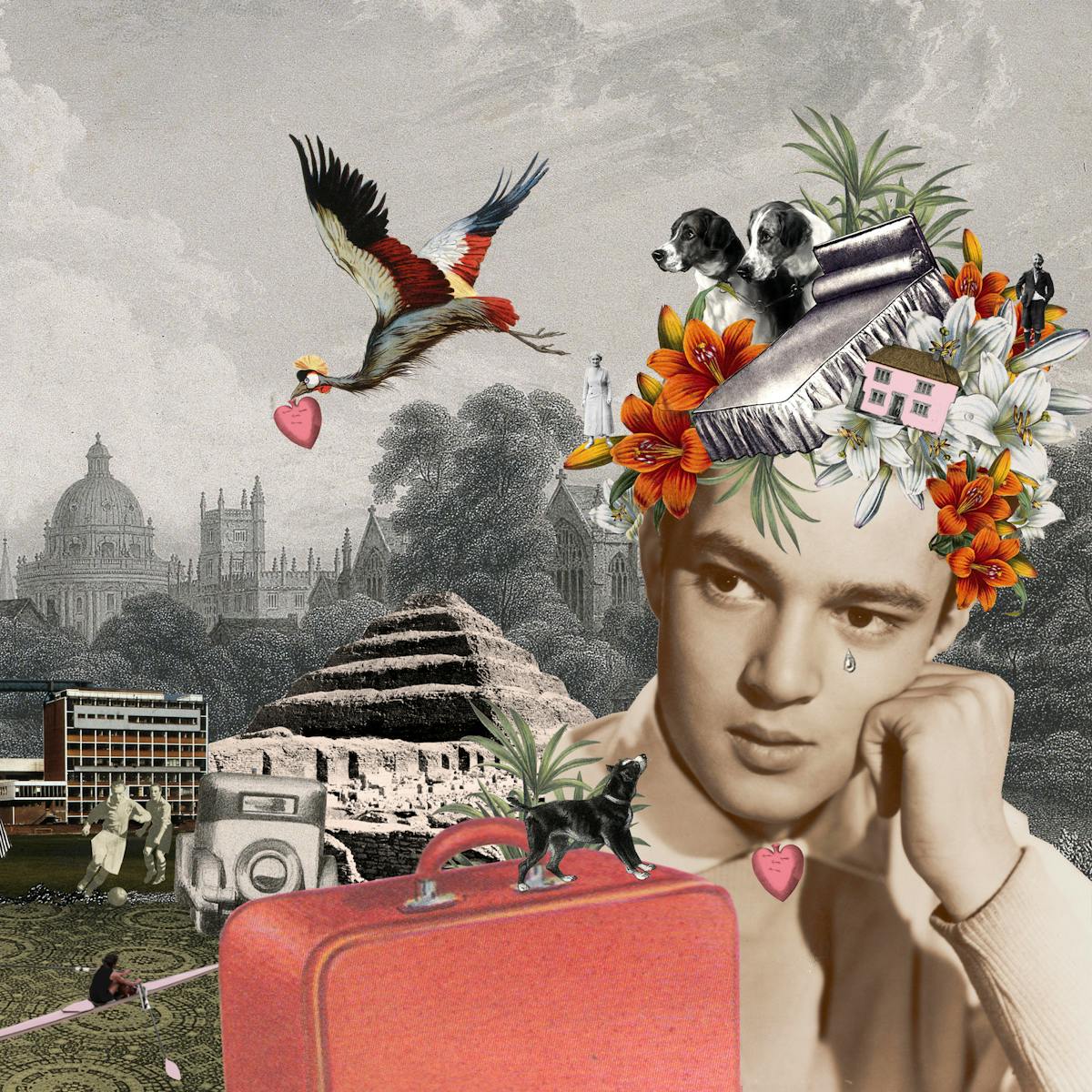

Words by Gail Tolleyartwork by Maria Rivansaverage reading time 6 minutes

- Serial

It is 1994, I am nine years old and I have just had an invitation to a sleepover. Sleepovers in the mid-1990s involved watching ‘Mrs Doubtfire’ on VHS and making friendship bracelets, while another child’s mother served up neon concoctions made with a SodaStream. In short, it should have been every child’s dream weekend. And yet I am feeling mostly dread. You see, as a child I suffered from terrible homesickness. The thought of even one night in a bed that wasn’t my own was terrifying.

Thankfully, as an adult, I’ve managed to shake off that unsettling fear. And now, ironically, I’m obsessed with travel. I’ve even managed to make it part of my job as a writer. But despite my newly acquired love for a nomadic life, I’ve never forgotten the feeling of homesickness that had such a grip on me. In fact, I’ve become increasingly intrigued by it.

In 2013 BBC reporter Tom Heyden wrote a feature on adults suffering severe homesickness. It was the first piece I had come across about the experience that explored it as a genuine, debilitating affliction. The article included the story of footballer Jesus Navas, who suffered from homesickness so badly that it stopped him playing for Spain. And Olympic rower Kate Copeland, who almost quit the sport after being struck with homesickness when she had to relocate from Teesside to the south of England for training.

I wanted to know more about what homesickness actually was. In popular usage it has an almost poetic connotation, but if it has the power to scupper dreams and stall careers, then maybe it's something more potent? Is it a psychological or medical condition? And why, for some of us, is it such an all-consuming feeling?

“Footballer Jesus Navas suffered from homesickness so badly that it stopped him playing for Spain. And Olympic rower Kate Copeland almost quit the sport after being struck with homesickness when she had to relocate to the south of England.”

Disconnection and existential loss

Dr Fred Cooper is a research associate at Exeter University. He’s currently working on a project about loneliness among students, which is part of the Wellcome Centre for Cultures and Environments of Health. Although he’s a historian, his work also draws on disciplines including geography, cultural studies and public health. I was intrigued to see what he’d make of homesickness from an academic perspective.

There’s something about where you grew up and the place you’re homesick for that is really psychologically complex.

“It’s one of those words that everyone thinks they know what it means. But when you unpack it, it actually relates to so many different things,” he explains. “There’s something about where you grew up and the place you’re homesick for that is really psychologically complex and working on lots of different levels.

“So homesickness could be feeling disconnected from the people who make a place a home. But there’s also so much about an environment and where and how people feel like they belong. It’s something that comes up with students all the time.

“They talk about belonging as being an antidote to feeling lonely. Sometimes that’s belonging in terms of a group, or going to the pub, or spending time with friends. But sometimes it’s the feel of a place or how people react to a new city.”

Another person who’s spent a lot of time thinking about the idea of home and what it means to leave it is psychotherapist Sarah Temple-Smith. She works for the Refugee Council and oversees the My View project, which provides help for child refugees in the UK. Like Fred Cooper, she emphasises that the idea of home is a complicated one that permeates every part of our lives.

“Homesickness could be feeling disconnected from the people who make a place a home.”

“We talk about loss of home for refugees as existential loss. When a young person sits in the therapy room and their body slumps and tears roll down their face, that’s what they’re experiencing – if you’ve lost your home, you’ve lost everything.” She goes on to explain that home incorporates far more than the building you grew up in. It’s also more than your familial relationships – home is how we relate to everything around us.

“To have your home shut its doors to you – for whatever reason – it’s like someone’s cut your legs off. You can no longer stand upright, you can no longer move yourself. It’s attachment in its absolute sense of being part of your world.”

Nomads of the 21st century

I had never heard someone describe home in such a profound way, but Sarah Temple-Smith’s explanation gave me an insight into why homesickness could be so destabilising. It is also clearly something that is experienced on a spectrum, and at its milder end it’s also incredibly common.

One study from 2002 by researchers at Utrecht, Oxford and Cardiff universities, published in the British Journal of Psychology, found that in the UK as many as 80 per cent of students missed friends and family, and found it difficult to adjust to college life. And while homesickness is often associated with students, it’s not something that’s unique to those populations.

Despite the widespread and sometimes significant impact of homesickness, there is surprisingly little research into it. Searching through the ‘Oxford Dictionary of Psychology’, I found that homesickness is not mentioned once. And I’m not alone in my impression that the topic has been overlooked.

Dr Fred Cooper again: “I never hear enough about it, and when I do, it tends to be thrown about in a really uncritical way, a bit like loneliness. People use the word and then they don’t really do any deep thought about where it comes from or what it actually means.”

“Home incorporates far more than the building you grew up in. It’s also more than your familial relationships – home is how we relate to everything around us.”

And that – from the perspective of 2020 – seems strange, because the 21st century has seen more people upping sticks and moving to a new city or country than at any other point in history. A Gallup World Poll published in December 2018 found that 15 per cent of the world’s adults would move to another country if they had the opportunity.

That’s 750 million people ready to pack their bags and say goodbye to their home town. And a lot of individuals who could feel the effects of homesickness. Could homesickness be due a moment in the spotlight?

A complex experience

And what about our relationship with home right now? The Covid-19 pandemic has caused many of us to think about home in a different way. Some have been stranded abroad, desperate to get a return flight. Others have found isolation – confined within the same four walls – more than they can stand. How we think about home is morphing in front of our eyes.

Over the next five chapters I’ll be poking and prodding this term ‘homesickness’, attempting to find out more about what it actually is and looking closely at what it can tell us about life in the 21st century.

Taking in epidemics of nostalgia in the 18th century, NASA scientists looking at homesick astronauts, and generations of homesickness in refugee camps, this series will consider why home – and leaving it – is a far more complex experience than you might ever have considered.

About the contributors

Gail Tolley

Gail Tolley is a travel and culture writer based in Edinburgh. She has twice been the editor of popular culture magazines: Time Out London (2017–19) and The List (2012–14). She has contributed to National Geographic Traveller, the Independent and BBC Radio 4. Alongside working as a freelance writer and broadcaster, she also works in TV development.

Maria Rivans

Maria Rivans is a contemporary British artist known for her Surrealism-meets-Pop-Art aesthetic. With its unique approach to collaging, her artwork intertwines fragments of vintage ephemera, often with reference to film and TV, to spin bizarre and dreamlike tales. She exhibits work throughout the UK as well as internationally, including Hong Kong, New York and across Europe. Notable solo shows include the Saatchi Gallery, London and Galerie Bhak, Seoul.