During World War I facial injury was often portrayed as the “worst loss of all” – a loss not just of appearance, but of identity, and even humanity. Suzannah Biernoff looks back at the surgeons and sculptors involved in the experimental work of facial reconstruction.

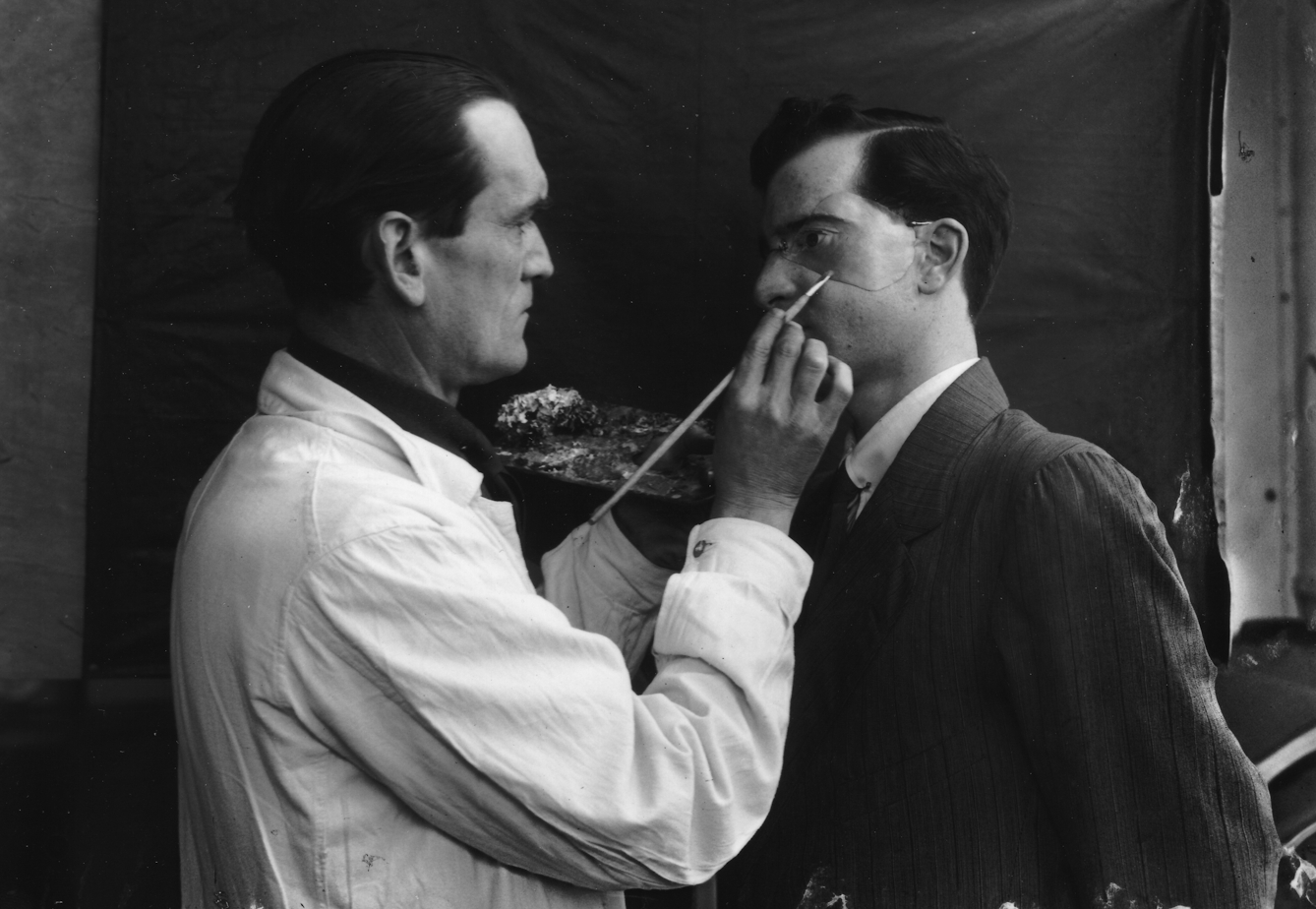

As Official Photographer of Great Britain during World War I, Horace Nicholls was commissioned to make a record of the war at home: the great munitions factories and shipyards, training camps, new recruits and soldiers on leave. A handful of these photographs record the laborious crafting of facial prosthetics undertaken by the sculptor Francis Derwent Wood, who had persuaded the commanding officer of the Third London General Hospital in Wandsworth to let him make bespoke masks for severely disfigured servicemen. Here we see Wood completing his artwork – a perfect fragment of cheek and eye.

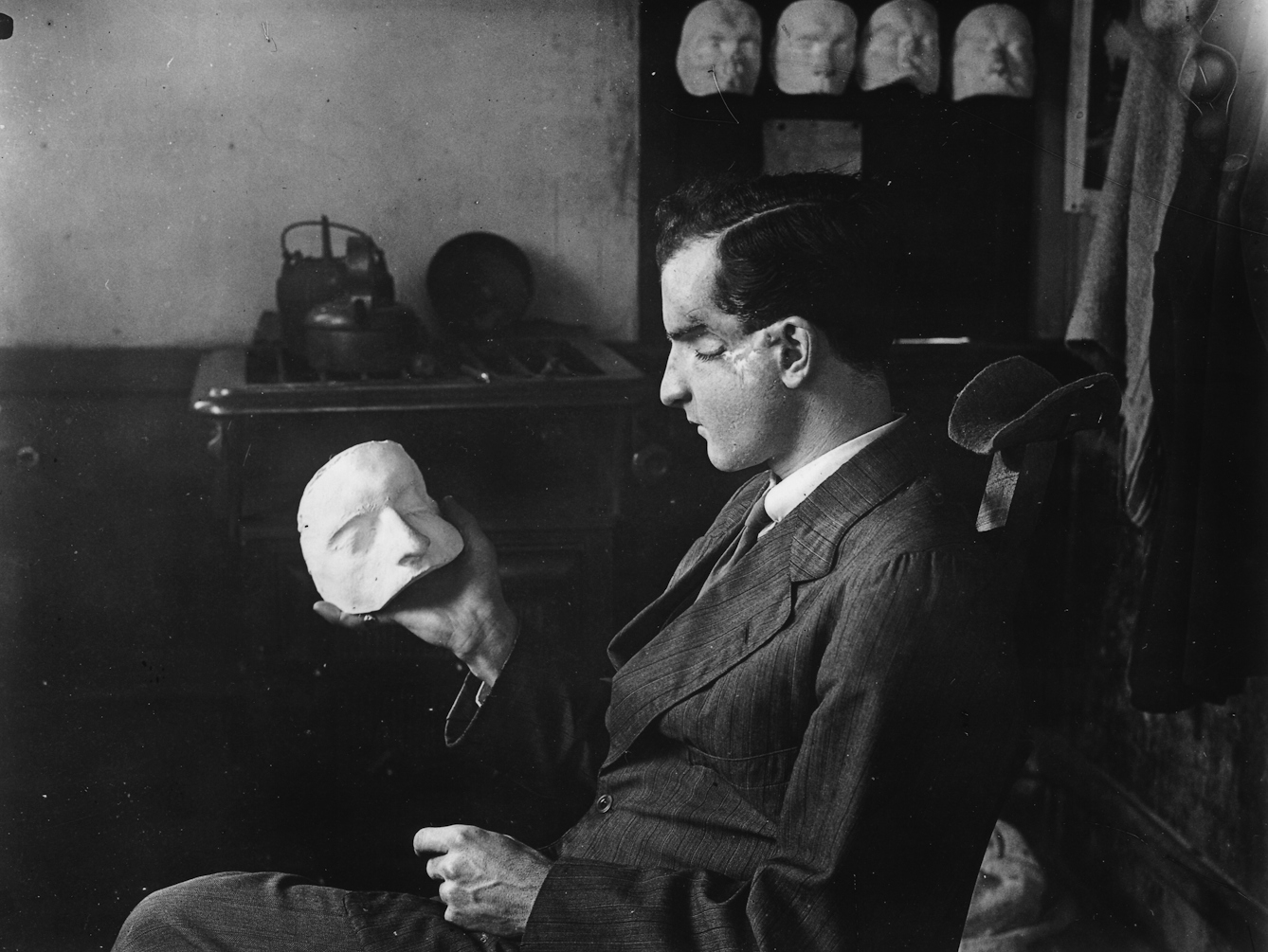

Wood’s ‘Tin Noses Shop’ employed four sculptors, a plaster-mould maker and a casting specialist. Wood and his colleagues would painstakingly recreate the patient’s original appearance from remaining features and pre-injury photographs. Here the patient and his ghostly plaster double come face to face. This plaster mask would then be coated with silver and painted to match the texture and tone of the patient’s skin. Eyebrows were painted on hair by hair and eyelashes of thin metallic foil were tinted, curled and soldered in place.

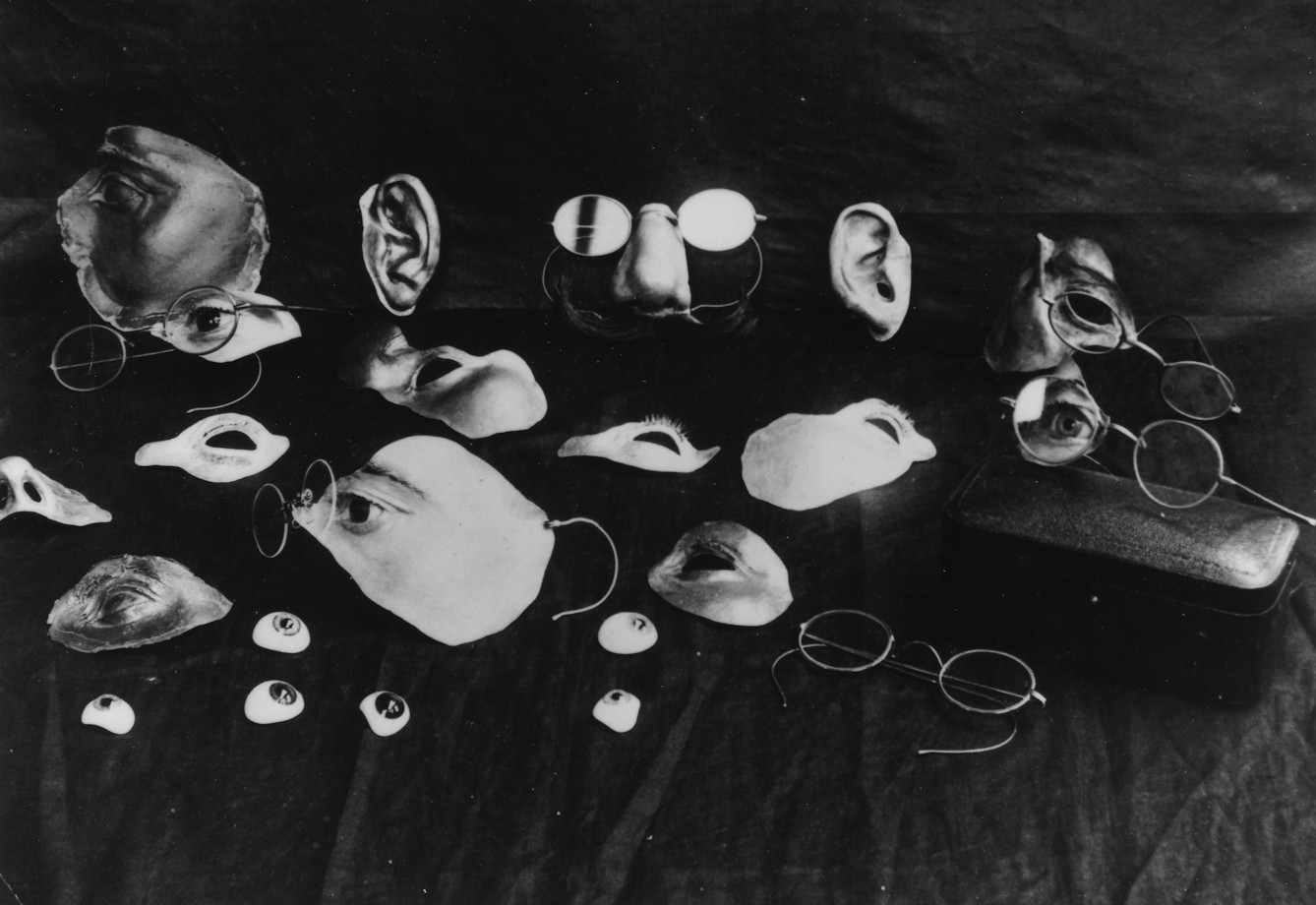

A final print shows an array of plates and masks at various stages of completion. Each plate was effectively a part-portrait of the sitter, meticulously brought to the verge of life. Although the masks could not restore physical function, Wood believed they had the potential to ameliorate psychological pain and social isolation.

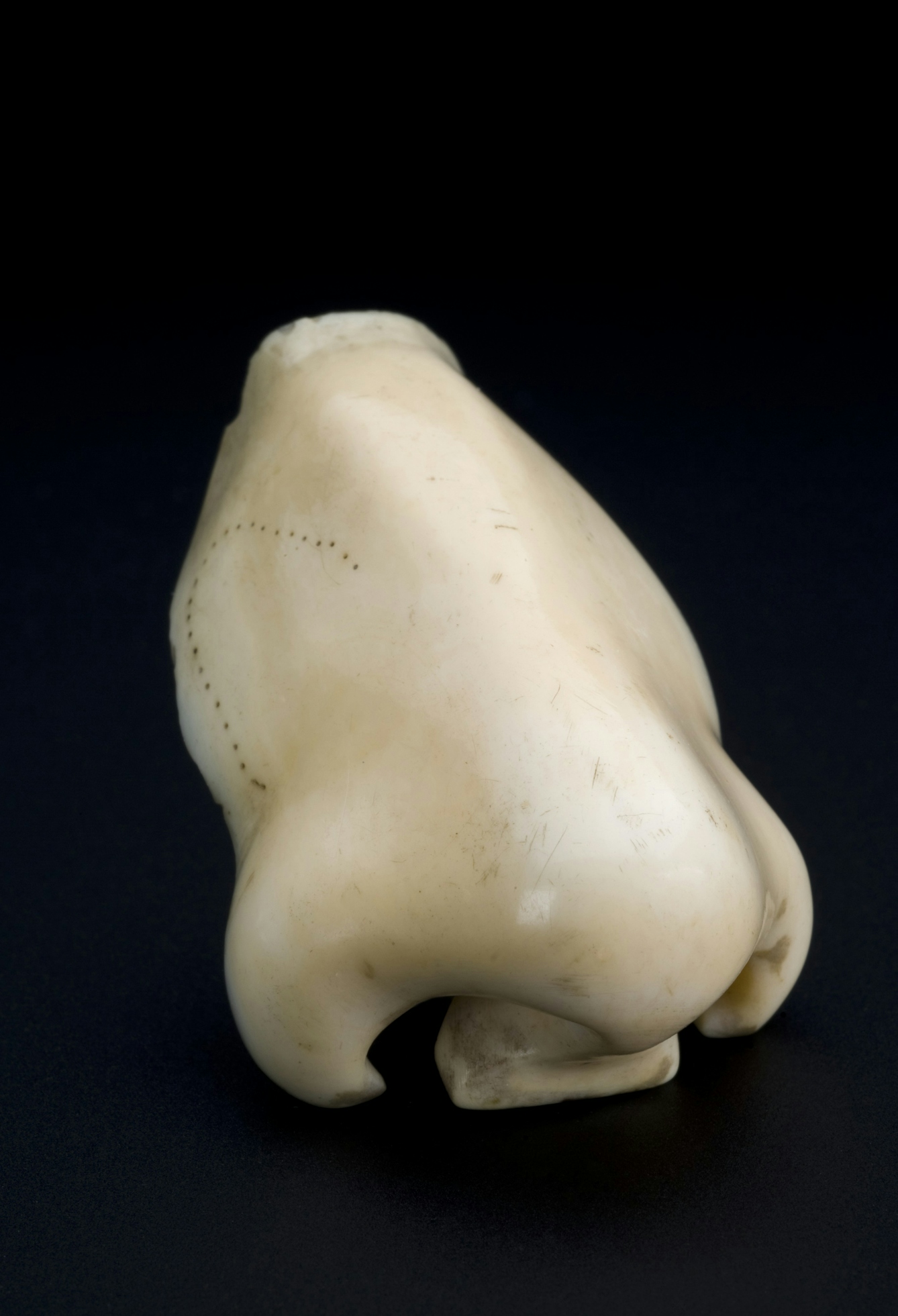

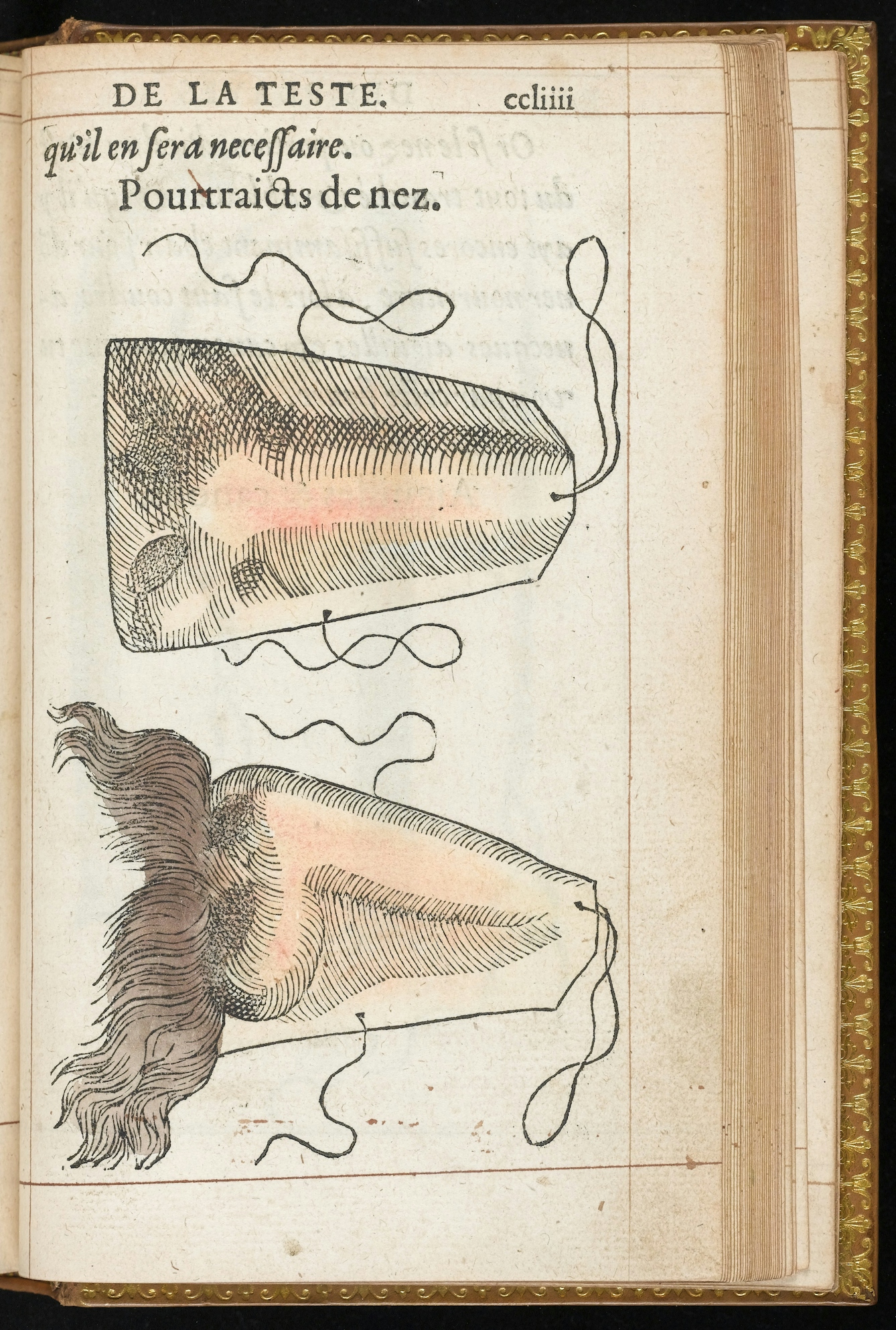

Facial masks, patches and artificial noses had been made for centuries to cover the disfiguring injuries caused by disease and combat. Henry Wellcome collected half a dozen noses like the one pictured here. The 16th-century French surgeon Ambroise Paré tells the story of a young man whose silver nose is a source of hilarity among his friends. He sets out to find a “master remaker of lost noses” in Italy and returns with a nose that everyone agrees is a great improvement.

Paré’s writings contain illustrations of enamelled eyes, prosthetic ears and noses, palatal obturators (which covered an opening in the roof of the mouth), mechanical limbs and an artificial penis crafted from wood or tin. Nicholls and Wood were most likely unaware of this longer history of facial repair, but they would have been attuned to the stigma of the missing or sunken nose associated with syphilis. In Gaston Leroux’s ‘Phantom of the Opera’, the Phantom‘s disguises include a “long, thin, and transparent” nose and another made of pasteboard with a moustache attached.

Facial injury was rarely depicted in the illustrated press and almost never in official war art or propaganda. John Hodgson Lobley’s orderly paintings of the Queen’s Hospital in Sidcup are an exception, showing the patients learning carpentry, bookkeeping and toy making in the hospital workshops. An official war artist for the Royal Army Medical Corps, Lobley portrays individual faces, some of them visibly scarred. Bandages suggest a process of healing, and conceal the most disfiguring injuries.

Henry Tonks was a surgeon before his success as an artist and instructor at the Slade School of Fine Art in London, and his pastel studies of plastic surgeon Harold Gillies’ patients before and after reconstructive surgery lie somewhere between medical illustration and portraiture. Tonks never thought of these intimate drawings as ‘war art’, but they portray the violence of war – and the transformative impact of injury – in a way that still has the power to shock.

A second workshop for portrait masks opened in Paris in November 1917 under the auspices of the American Red Cross. Its director, Anna Coleman Ladd, had established a name for herself as a sculptor before the war, with portrait commissions from society figures, including prima ballerina Anna Pavlova. Ladd and her associates took over a large fifth-floor artist’s studio in the Latin Quarter: a bright, high-ceilinged room decorated with posters, flowers and an American flag.

In a silent film commissioned by the American Red Cross, the studio at 70 Rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs comes to life. Three uniformed mutilés are having new features sculpted, painted and fitted. One of them takes the cigarette from his mouth, reaches behind his ear and, with a smile, removes his chin. His compatriots seem just as comfortable in the company of Ladd’s assistants, nodding and chatting while the sculptors make adjustments.

The Paris Studio for Portrait-Masks served a social as well as therapeutic function. There was a regular Tuesday tea, and at any one time there might be half a dozen visitors: the men we see in the photographs and film, but also surgeons and curious members of the public.

Ladd recollected that the men, who often arrived with flowers, would stay on for a game of dominoes or checkers: “The blind ones played dominoes and the others checkers. We served them chocolates, cigarettes and their favourite vin blanc ... They were never treated as though anything were the matter with them. We laughed with them and helped them to forget.”

One wall of Ladd’s studio was decorated with rows of plaster casts; finished plates were arranged on a makeshift tablecloth with a vase of lilies. These strange, exquisite artefacts are an object lesson in how the war-damaged face was understood at the time as a psychological and social wound. Though short-lived, the portrait mask experiment shows facial injury and repair being collectively managed, by surgeons and artists, in ways that challenge our assumptions about the purpose of both science and art.

About the author

Suzannah Biernoff

Suzannah Biernoff is a Reader in Visual Culture in the School of Historical Studies at Birkbeck, University of London. Her publications, focusing on ideas of the body and the self, include ‘Sight and Embodiment in the Middle Ages’ and ‘Portraits of Violence: War and the Aesthetics of Disfigurement’. She is currently working on a history of imperfection, tracing connections between early 20th-century plastic surgery and psychotherapy, changing understandings of disability, and contemporary discussions of self-care and authenticity. Arguing that imperfection is a foundational modern idea, the book will suggest new ways of thinking about the cultural preference for flawless perfection.