From the first documented case of mouth-to-mouth resuscitation in 1732, through the 20th century’s polio epidemic, to coronavirus patients today. Find out how developments in breathing support have been driven by the doctors encountering victims of smoke inhalation, near-drowning and debilitating viruses.

It was a cold morning in December 1732. In Alloa, Scotland, James Blair made a descent into the depths of the local colliery, along with several other miners. Weeks before there had been a fire in the mine, prompting the authorities to seal it off in order to smother the flames. When the mine was reopened, Blair was among the first to enter its access shaft.

As the miners reached the bottom, however, they began to choke on thick smoke trapped in the deepest chambers. The men scurried up the ladder, gasping for air. As they reached the top they realised that Blair was still 60 metres below ground.

William Trossach, the town’s doctor, arrived at the scene just as a team of rescuers pulled Blair from the shaft. The miner was not breathing and had no detectable pulse. Trossach later described what he did next: “I applied my Mouth close to his, and blowed my Breath as strong as I could, but having neglected to stop his Nostrils, all the Air came out at them.”

After a faltering start, Trossach realised that pinching the nostrils would prevent the immediate escape of air, and so he tried again. Blair soon regained consciousness and was able to return to work a week later.

Although he didn’t invent the technique, Trossach’s description provides one of the earliest documentations of a person being successfully revived by mouth-to-mouth resuscitation.

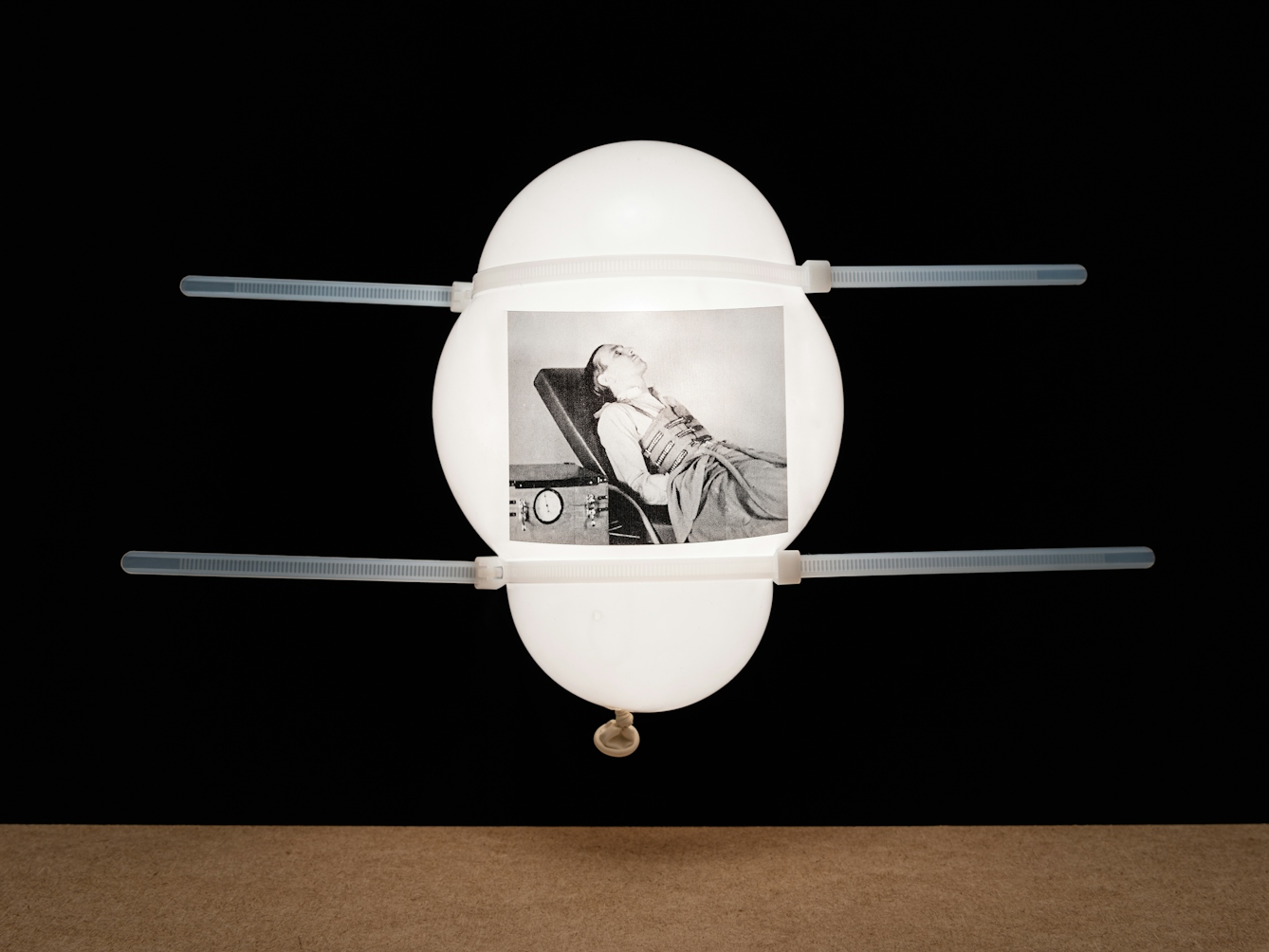

With the Bragg-Paul Pulsator, the patient is not enclosed. Instead they lie in an elevated position with their chest rhythmically subjected to positive pressure. Still from the film ‘Artificial Respiration’ (00:06:35), made in the 1940s.

The simple act of breathing, which is so vital to life, is something that we take for granted. And in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, compromised respiration is now at the forefront of everybody’s minds. But finding better and more efficient delivery systems for life-giving air to the lungs has been a preoccupation of the medical community for hundreds of years.

Experiments on dogs and drowning victims

Long before Trossach successfully performed mouth-to-mouth resuscitation on James Blair, the Flemish anatomist Andreas Vesalius described an early form of positive pressure ventilation, which he performed on a dog in 1543. Vesalius made an opening in the animal’s trachea and inserted a reed tube. It was through this conduit that he then blew air into the dog’s lungs.

Today, medical professionals would recognise this technique as a tracheotomy. Vesalius’s experiment demonstrated the power of mechanical ventilation – though it would not be incorporated into widespread medical practice for several more centuries. This was partly due to the fact that doctors did not yet fully understand the purpose of respiration.

At various points along the River Thames the organisation placed resuscitator kits containing bellows that could be used to blow tobacco smoke into the lungs, the stomach, or even the rectum!

A breakthrough arose in the 1770s, when the chemists Wilhelm Scheele, Joseph Priestley and Antoine Lavoisier independently discovered oxygen. Shortly afterwards, this element’s essential role in respiration was realised. Ironically, this led to the temporary discontinuation of mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, since doctors worried that exhaled air might lack the vital agent, oxygen. (In reality, exhaled air contains 16 per cent oxygen. Although this is lower than atmospheric air, which contains 21 per cent oxygen, it is still sufficient for resuscitation.)

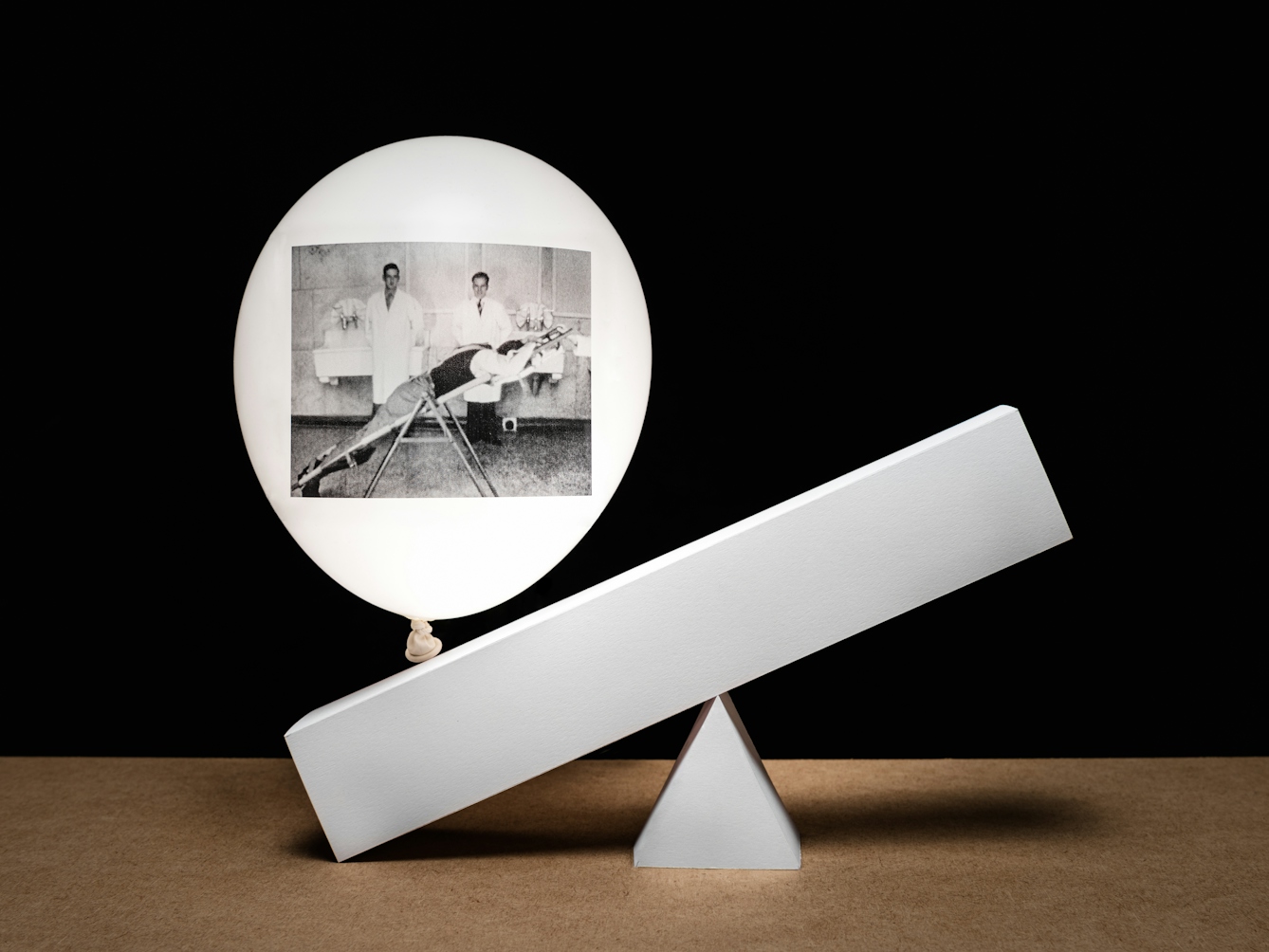

The rocker is a stretcher with a central pivot. The patient lies face down on the floor, and is picked up and placed in the contraption. The weight of the abdominal contents, acting through the diaphragm, increases and decreases the capacity of the thorax. Still from ‘Artificial Respiration’ (00:16:56).

In the wake of these developments, interest in mechanical ventilation increased. It was around this time that the Society for the Recovery of Persons Apparently Drowned was established in England. To encourage resuscitation attempts, the organisation offered cash prizes to those who could prove they had successfully revived a victim of drowning.

This led to some truly bizarre experiments involving tobacco smoke, which some people believed combated cold and drowsiness. At various points along the River Thames the organisation placed resuscitator kits containing bellows that could be used to blow tobacco smoke into the lungs, the stomach, or even the rectum!

It wasn’t until the 19th century that mechanical ventilators began to appear, and these were based on principles that doctors might recognise today. One such machine was a tank respirator invented in 1832 by the Scottish physician John Dalziel. The patient sat upright in an airtight box with only their head and neck poking out. Air pressure was alternately increased and decreased by a pair of bellows inside the box, which was worked from the outside by a piston rod and a one-way valve. This facilitated inhalation and exhalation by causing expansion and contraction of the chest cavity in a way that mimicked natural breathing.

Other designs followed. It was these early forms of negative-pressure ventilators that paved the way for what would eventually become known as the iron lung.

Polio and paralysed patients

In the first half of the 20th century polio was the leading cause of death in children and young adults. In extreme cases, the virus can cause spinal and respiratory paralysis, making it impossible to breathe. Few diseases were more dreaded by parents. An outbreak in Brooklyn in 1916 led to the widespread closure of cinemas, parks and swimming pools. The names and addresses of the infected were published daily in newspapers. Warning notices were nailed to their doors, and entire families were forced into quarantine.

The 1937 Both respirator is a modification of the Drinker respirator, invented in the late 1920s. The patient is totally enclosed, and the pressure inside is raised and lowered by a pump. There are side portholes for access. Still from ‘Artificial Respiration’ (00:04:10).

By the 1920s, the situation had reached critical mass. One day Philip Drinker – an industrial hygienist from the Harvard School of Public Health who specialised in air safety – visited a hospital to consult on a problem with the air conditioning. The sight of dying children with paralysed diaphragms, however, affected him deeply. With the help of his colleague Louis Agassiz Shaw, Drinker began engineering the world’s first iron lung.

Powered by a motor, the iron lung acted like a vacuum – creating and releasing pressure around the body to simulate breathing, while the patient was prostrate inside the hulking contraption. Drinker’s respirator was first used in 1928 at Boston Children’s Hospital, and successfully treated an eight-year-old girl. Over the next several decades, it underwent various design makeovers.

The iron lung saved countless lives. Many patients recovered the ability to breathe independently after a few weeks, but some had to spend their entire lives inside the metal cylinder. It was only in 1955, after Jonas Salk developed the first safe and effective polio vaccine, that cases began to decline, and the need for iron lungs tailed off.

The medical establishment began experimenting with new forms of positive pressure ventilation. In the 1960s respirators emerged that were inspired in part by breathing apparatus used by pilots during World War II. These ultimately gave rise to the ventilators we see in hospitals today.

As healthcare professionals combat the coronavirus pandemic, efficient mechanical ventilation has taken on new urgency. The shortage of equipment in the face of growing numbers of patients needing respiratory assistance may lead to novel engineering solutions that usher in a new generation of life-saving technology. Necessity truly is the mother of invention.

About the contributors

Dr Lindsey Fitzharris

Dr Lindsey Fitzharris is a bestselling and award-winning author with a doctorate in the History of Science and Medicine. Her debut book, ‘The Butchering Art’, won the 2018 PEN/E O Wilson Award for Literary Science and was shortlisted for both the Wellcome Book Prize and the Wolfson History Prize.

Steven Pocock

Steven is a photographer at Wellcome. His photography takes inspiration from the museum’s rich and varied collections. He enjoys collaborating on creative projects and taking them to imaginative places.