Although for centuries people thought that the stars could have a malign influence on Earth, 20th-century space exploration made that threat more tangible. Taras Young explores ideas that diseases from outer space might have plagued humanity for millennia, and why some scientists are convinced this is true.

Most of us think of diseases as something caught from contact with other people, animals, or contaminated air or surfaces. But what if the viruses and bacteria that make us ill came not from earthly sources, but from the far reaches of outer space? It may sound like something straight out of a science-fiction story, but the idea that diseases might be extraterrestrial in origin is one that has been proposed and debated by some surprisingly eminent scientists.

The belief that the cosmos can exert a negative influence on human life is deeply rooted in cultures around the world. Ancient written records from China and Rome show that comets, in particular, were thought to be bad omens. In the sixth century, Isidore of Seville wrote that comets “are born suddenly, portending a change of royal power, or plague, or wars, or winds and heat”. Shakespeare described his ill-fated lovers as “star-crossed”, and when the first flu pandemics took place during the 16th century, Italian physicians attributed the new disease to influenza di stelle – the influence of the stars – giving the illness its familiar English moniker.

In the 20th century, the dawn of space exploration meant humans would, for the first time, intentionally come into contact with materials from beyond the Earth. In response to this new era of discovery, biological hazards from other worlds quickly became a trope in science fiction: ‘The Blob’, a film released in 1958, depicted an alien amoeba escaping from a crashed asteroid and growing to engulf several Pennsylvania towns. Now scientists in the real world had to take the risk of cosmic cross-contamination seriously.

In 1960, the US government’s Space Science Board advised NASA that any materials brought back should be treated as a potential biological threat. They were keen to avoid the tragic irony of humanity’s discovery of life in space leading to the end of life on Earth. So, as work began on the first manned Moon mission, a committee on “interplanetary quarantine” was established.

Scientists at the agency believed the Moon was unlikely to harbour extraterrestrial life-forms; if there were any at all, they would be deep below the surface. However, they chose to act cautiously, not only because organisms which had been in stasis on the Moon might thrive and multiply on Earth, but because pristine lunar samples would be more valuable to researchers than ones contaminated with terrestrial organisms.

“When the first flu pandemics took place, Italian physicians attributed the new disease to influenza di stelle – the influence of the stars – giving the illness its familiar English moniker.”

Thus, when the Apollo 11 mission returned from the Moon in 1969, the samples and devices brought back were tested for biological hazards at the specially created Lunar Receiving Laboratory (LRL). Despite returning as heroes, the astronauts were forced to spend three weeks in quarantine at the LRL, making Neil Armstrong, who had just turned 39, a pioneer of the quarantine birthday.

The stuff of science fiction

NASA gave up on contamination testing and quarantine after 1971’s Apollo 14. Some within NASA had viewed the procedures as a waste of resources; however, a curious incident in 1969 may have caused them to think again. The Apollo 12 astronauts brought back a camera which had been taken to the lunar surface by the unmanned Surveyor 3 craft in 1967. When the device was analysed, the lab not only detected earthly bacteria on the camera – most likely from a technician breathing on it before launch – but found that the germs were still alive, despite having spent nearly three years on the Moon.

The idea that microbes could survive in the harsh climes of space was now grounded in real evidence. And, although no alien germs had been found, the concept continued to be a source of inspiration for science fiction: the same year as the Apollo 11 and 12 missions, Michael Crichton’s hugely successful novel ‘The Andromeda Strain’ captivated readers with the story of a crashed satellite bringing back a deadly, rapidly mutating, extraterrestrial virus.

Across the Atlantic, the notion of diseases arriving from the stars was being given serious thought by British astronomer Sir Fred Hoyle. Hoyle had long been interested in where things came from: he proposed the theory of stellar nucleosynthesis – which remains our best explanation of how elements are formed – and coined the term ‘Big Bang’ for the creation of the universe (though he rejected the idea itself).

“The idea that microbes could survive in the harsh climes of space was now grounded in real evidence.”

For more than 25 years, he had led a distinguished career at the University of Cambridge, but after being knighted in 1972, he resigned his academic positions to pursue his interest in the possibility that the origin of life was in the stars.

They theorised that novel viruses and bacterial infections might literally peel off and “drift down onto the surface” of the planet, in a sort of cosmic miasma.

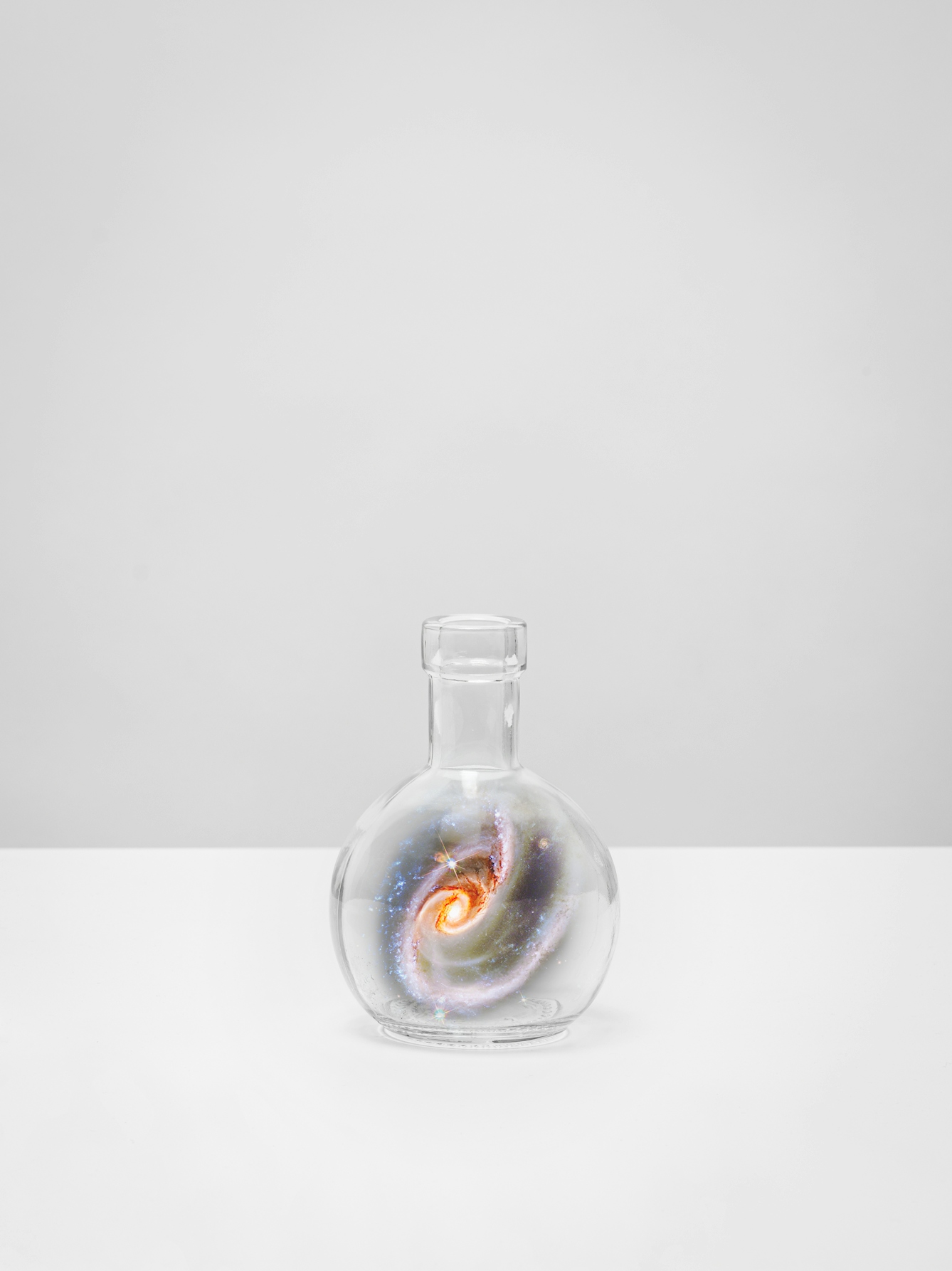

In 1977, together with a former doctoral student, Professor Chandra Wickramasinghe, Hoyle penned an article for the New Scientist titled ‘Does epidemic disease come from space?’. The scientists claimed that comets might be shedding biological material as they zoom past Earth, in what they called “extraterrestrial biological invasions”.

They theorised that the interstellar bodies could be hosting repeated attempts by microbes to evolve, and that novel viruses and bacterial infections might literally peel off and “drift down onto the surface” of the planet, in a sort of cosmic miasma.

To back this up, the authors cited sudden, deadly pandemics which were detected in multiple places at once, or which spread more rapidly than seemed intuitive. These included the Spanish flu of 1918, the plague of Athens in 429 BCE, and “almost all earlier as well as later epidemics”.

“Hoyle and Wickramasinghe claimed that comets might be shedding biological material as they zoom past Earth, in what they called ‘extraterrestrial biological invasions’.”

Scientists swimming against the tide

The article was immediately controversial, and biologists criticised its ideas as being highly improbable. However, Hoyle and Wickramasinghe continued to pursue the notion, publishing a follow-up article in 1979, titled ‘Influenza from space?’. Based on data the pair collected on patterns of sickness and absence at British boarding schools that year, they came to the conclusion that the H1N1 virus had not spread through person-to-person contact, but rather “descended through the atmosphere and settled with an exceedingly fine-scale patchiness at ground level”. The same year, they distilled their ideas into the popular book ‘Diseases From Space’.

Hoyle died in 2001, but Wickramasinghe, together with a few other scientists, continues to advocate the theory that diseases come from the stars, contrary to mainstream scientific opinion. In a 2003 letter to the Lancet, he extended the idea to SARS, suggesting an extraterrestrial virus may have arrived in the thin atmosphere of the Himalayas before spreading to China, where it had first been detected. And, in 2020, he proposed that Covid-19 had arrived on a meteor that lit up the skies over northern China in October 2019 – despite the fact that SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19, is closely related to the earlier SARS virus.

Just as the Romans who claimed comets were bad news were refuted in their own time – Seneca, writing in the first century, correctly identified them as celestial bodies in orbit around the Sun – so mainstream scientists refute the idea of cosmic origins for earthly diseases.

The “diseases from space” hypothesis is considered by some to be overcomplicated when conventional theories already explain how diseases evolve and spread. In relation to recent pandemics, it has also been pointed out that coronaviruses such as SARS and Covid-19 could not survive the types of radiation found in space.

Even so, it seems the draw of the cosmos will continue to lead some to investigate whether humanity’s fate really is written in the stars.

About the contributors

Taras Young

Taras Young is a researcher and writer interested in weird, hidden and forgotten ideas. He is the author of Apocalypse Ready, a new illustrated history of 20th century public information on pandemics, natural disasters, nuclear war and alien invasion.

Steven Pocock

Steven is a photographer at Wellcome. His photography takes inspiration from the museum’s rich and varied collections. He enjoys collaborating on creative projects and taking them to imaginative places.