Carmel King and Clare Dowdy celebrate the life and work of Lawrence Jenkin, a legend of the frame-making business. Now in his 80s, he continues to provide inspiration and practical support to new generations of glasses designers.

Lawrence Jenkin was born into the eyewear business 80 years ago and, as one of the last of his generation, is keeper of the complex secrets of traditional spectacle frame-making. A hugely successful designer, he’s helped and influenced many of the new generation of frame makers.

His father’s company, Anglo American Optical, imported spectacle frames, and as a child in the 1950s, Jenkin spent his holidays in the workspace near Hampstead Heath, north London. There he was taken under the wing of the caretaker George Lowe, who was also a frame maker. “We hit it off,” says Jenkin, “and he steered me towards the design and making route. George was a very important man in my life.”

After qualifying as an optician, Jenkin got a job in the USA at Lugene Opticians in Manhattan. Its fabulous client list was teeming with film stars. “I fitted glasses on Greta Garbo and Kirk Douglas,” he says.

He moved to Vision Limited on Third Avenue, where he learned about “selling glasses, giving people things they wanted or didn’t know they wanted”. When his boss heard that Jenkin wanted to be a frame maker, “He wrote me a cheque for £10,000 and said, ‘Go ahead and do it.’”

In the late 1960s that money allowed Jenkin to buy the right machinery from France, Germany and Italy, and he set up his workshop back in the family’s Hampstead premises. In its heyday, Anglo American had more than 60 staff producing 2,000 frames a week – “We couldn’t make enough!” – and many of these were exported. Celebrity clients included Christopher Reeve in his Superman role, Dame Edna Everage, Elton John, Cher and Bobby Womack.

Lawrence Jenkin

The manufacturing shop floor in Brian McGinn’s east London atelier. When Algha Works finally shut its doors in 2020, McGinn invited Jenkin into the space, where he continues to design, develop and hand-make frames for clients across the world.

Jenkin’s frames are made of lightweight acetate, which is based on cotton or tree pulp. Cellulose acetate was introduced as an eyewear material in 1940, the innovative material earning a reputation for its durability and striking colours.

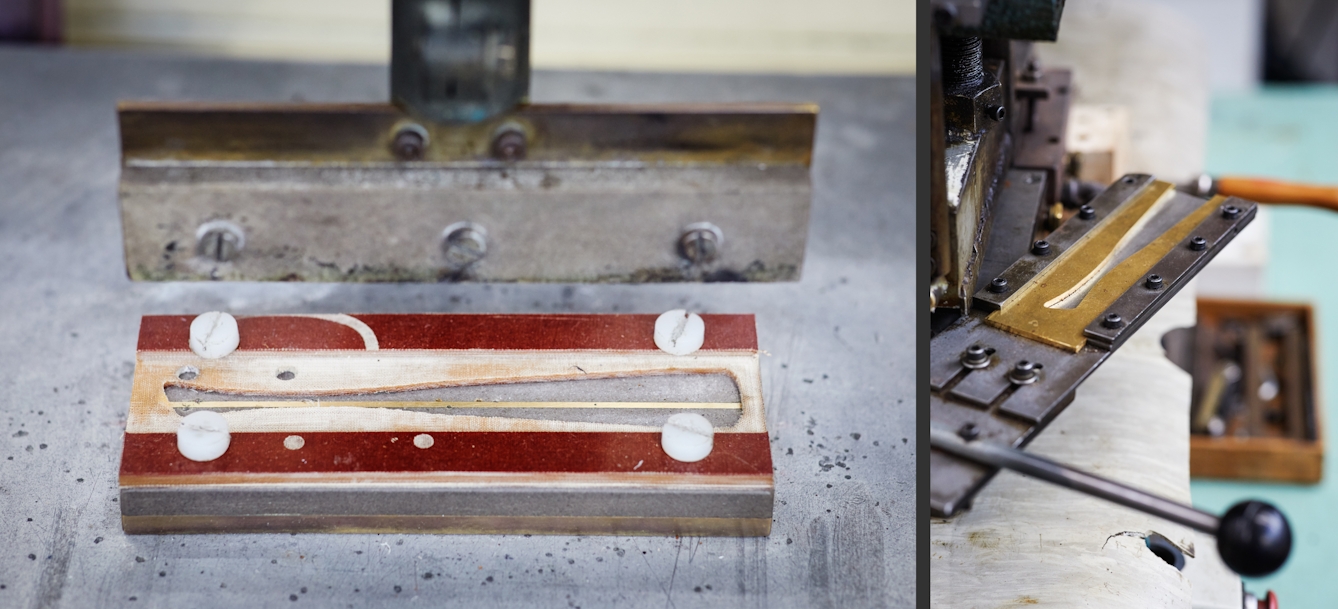

On the left is an old fly press used to cut out or form shapes in various materials. On the right is an old drill press, saved by Jenkin when the Algha Works closed.

Jenkin at his work bench. His list of clients have included Kim Basinger in the first Batman film and Christopher Reeves in the ‘Superman’ films, as well as Dame Edna, Andy Warhol and Elton John.

Component parts of spectacles, charting the development of styles using vintage acetates, from the late 1980s to the early 1990s.

Fashionable NHS specs

At that time, there were lots of eyewear manufacturers in London and the Southeast. “But very few of them employed designers,” Jenkin says. He was heavily influenced by the National Health Service frames, which were made by Algha Works and available free or at much-reduced cost to all between 1948 and 1985.

Algha was the brand name for Max Wiseman & Co., which was founded in 1898 and became the UK’s biggest manufacturer of metal and acetate frames, with branches all over the British Isles, and in Canada and Australia. The company’s 200-plus staff made up to half a million frames annually.

“They [the frames] were very good eye shapes for men, women and children,” he says, “but they were made cheaply and had quite small eye sizes, meaning they didn’t work as fashion items.” Jenkin’s inspired move was to combine the simple geometric shapes of the NHS frames with the generous styling of the American collections. And by adding his own flair, he created functional specs that doubled as fashion items in beautiful materials like Italian acetates.

Jenkin left the family business, and in 2010 set up his workshop at Algha Works on east London’s Fish Island. He lent his expertise to Algha’s production process and designed some frames for them. Over the years, the company has made frames for the Beatles and Harrison Ford in ‘Raiders of the Lost Ark’.

Rocco Barker

Rocco Barker in his basement workshop, opposite the Trellick Tower in west London. The workshop is full of his own handmade frames and vintage designs he collected while on tour of the US with his post-punk band Flesh for Lulu.

Barker describes spectacle-making as a cross between precision engineering and freehand sculpture.

Barker makes about ten frames a week under his brand Optical Works London.

It took Barker years to track down the machinery for his workshop. Some of it came from Algha Works after its closure in 2020.

There are over 50 processes to make each frame, including heating up the bridge and pressing it in the ‘bumping machine’ to make the raised area. He uses Italian acetate, which is malleable and, according to Barker, holds its shape better than plastic.

The godfather of frame-making

While the frame-making industry has largely died off in the UK, in recent times Jenkin has witnessed a mini-revival among a new generation of individuals who are fascinated by the process. “Making frames is hard,” he says, “it involves around 60 different steps.”

He has taken a string of these face-furniture fanatics under his wing, teaching them the process and helping guide their careers. For these enthusiasts, Jenkin is the godfather of frame-making, and the keeper of the craft’s secrets.

“Lawrence has had a massive impact on my career,” says Rocco Barker of Optical Works, “he’s a god.” After a career as a rock musician, Barker sold vintage frames from a little shop in Portobello, London. But he was keen to become a maker, and taught himself much of the process, collecting together old pieces of machinery or building his own.

It was Jenkin who taught him “the last pieces in the puzzle that I needed. I couldn’t have got that from anyone else.” Barker was also helped by Jenkin’s peers: the frame makers Colin Cheilman, Dave Cox and the late tool maker Peter Harold. Jenkin credits all three for their skill and deep knowledge.

Silver- and goldsmith graduate Brian McGinn “wanted to figure out how to make eyewear in a commercial way”. He knocked on Algha Works’ door, “as it was the only place doing small-batch production at the time”. There, he came across Jenkin working in the basement, and ended up working alongside him.

Brian McGinn

Brian McGinn outside his Powell Road atelier in Clapton, east London.

Barrel-polishing was developed to relieve laborious hours spent hand-polishing frames. The cut frames progress through four barrel chambers filled with small cedarwood lozenges and varying degrees of abrasive polishing compound. Pumice powder, when mixed with a binding oil, constitutes one of the four barreling stages.

On the left is a high-frequency heater, which was first developed in wartime to block enemy radio signals. In eyewear manufacturing, the high-frequency heater is used to soften the centre of a temple (arms/legs), prior to it being shot with a strengthening core wire. On the right is an old temple shooter salvaged from the closure of Algha Works in Hackney Wick in 2020.

McGinn hand-polishing an acetate sunglasses frame.

A selection of styles for McGinn’s evolving collection of handmade optical and sunglasses frames. As well as creating his own collections, he also works closely with costume and wardrobe designers to create eyewear for film and TV productions.

“Lawrence has a vast reservoir of experience from years in the business,” says McGinn, who has since designed or consulted for Prada, Oliver Goldsmith Sunglasses, YMC and ZanZan.

When Algha closed its UK manufacturing business in 2020, McGinn provided Jenkin with workshop space in Hackney. “In the past six months, I’ve watched him go through another creative burst,” he says of Jenkin. “In his 80th year, he’s still developing and thinking. It’s pretty inspiring.”

Alyson Magee’s eyewear brand Face à Face is based in Paris, and she’s currently working with Chanel. She first met Jenkin in 1984, when she was a young student at the Royal College of Art. She was keen to make eyewear, and a lecturer put her in touch with Jenkin.

“He opened up his door and never closed it,” showing her how to make frames and giving her access to materials like acetate. “He pointed me in the right direction after studies, suggesting I work for French-Armenian eyewear designer Alain Mikli.” She has discussed all her career decisions with Jenkin – “for me he’s like a spiritual father.”

While the big business of frame-making may not return to the UK, through Jenkin and his peers, the craft is finding a new home among a new generation of skilled makers.

About the contributors

Clare Dowdy

Clare Dowdy is a London-based freelance journalist, focusing on design, manufacturing and architecture. She is the author of 'Made In London: from workshops to factories', which was published by Merrell in 2022.

Carmel King

Carmel King photographs makers and manufacturers across the UK, documenting British craft and industry. She is particularly interested in capturing regions of the country that are known for specific crafts and long-running family firms, where skills and knowledge are passed down through generations. In October 2022 Merrell published ‘Made in London‘, which Carmel King co-authored with Mark Brearley, which looks behind the scenes of 50 workshops and factories across the capital.