Desperate for diversions during lockdown, David Jesudason started rummaging through skips and dustbins at night. Most of his finds were disappointing, but then he unearthed something that sparked an investigation into a forgotten piece of World War II history and the life of a talented but largely unknown female surgeon.

My world shrank during the pandemic, like it did for most people. As travel became restricted, and pubs and restaurants closed, variety drained out of my once busy urban life. To fill the void, I had to be imaginative. I started bin diving.

Rummaging around the household detritus of my neighbours would appear to be a cry for help, especially as I have a young family. Instead, it was a soothing practice that gave me some respite from juggling childcare and a demanding job.

When walking with my daughter I would scope out a skip or box of rubbish and return in the night, ready to discover something – anything – that would take me out of my normal routine.

The buzz from the illicitness of this pursuit often outweighed the results, which usually yielded nothing more than a soiled soft toy. I would wash such finds, only to discover they would be too dangerous for my four-year-old to play with.

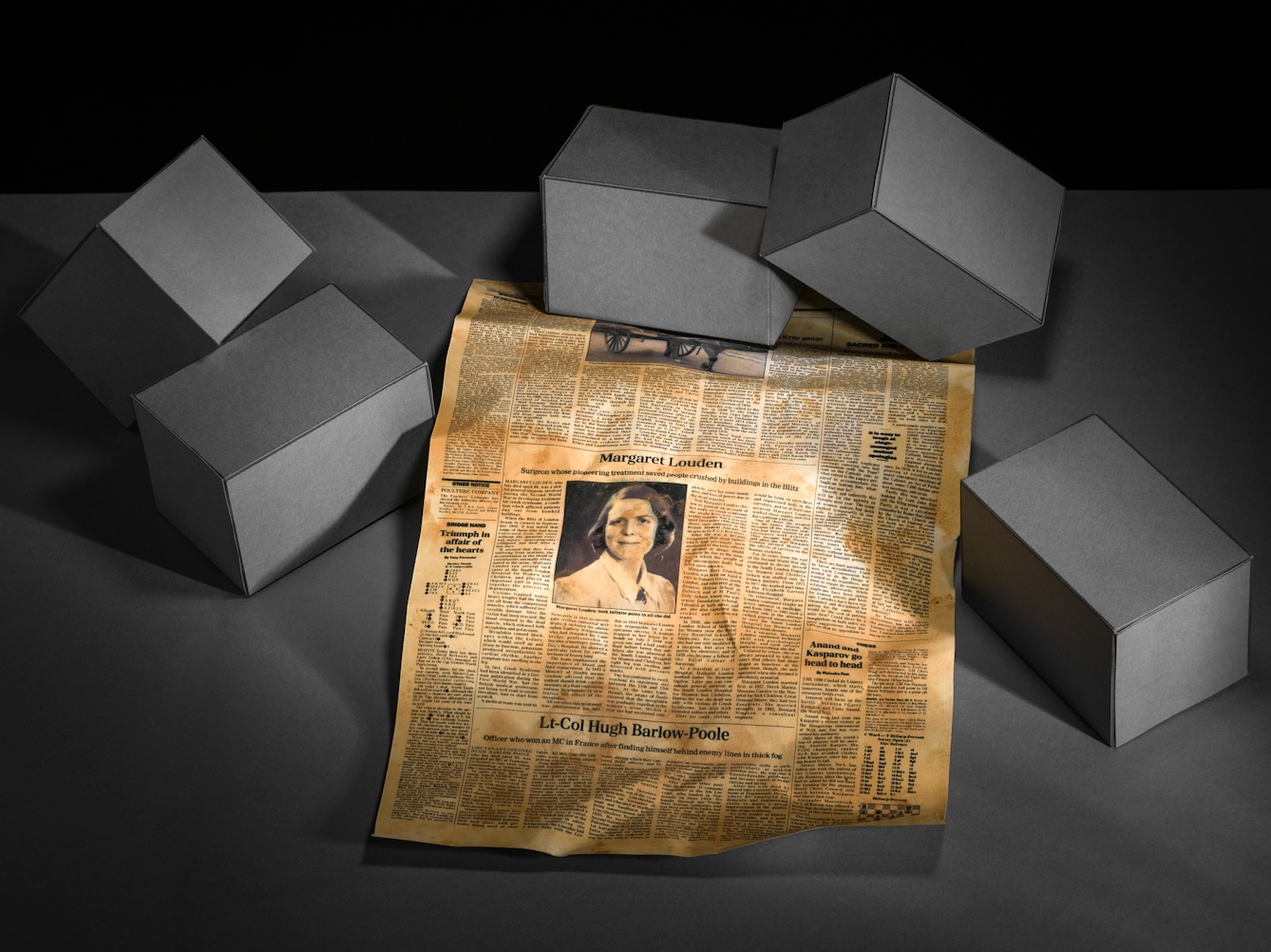

But everything changed the day I found a newspaper from the 1990s. The Telegraph’s distinctive broadsheet pages were dirty and ripped, but parts were still readable. The obituaries at the back contained the story of a woman I’d never heard of. Her name was Margaret Louden, a surgeon who’d qualified in the 1930s.

The obituary set me on a new path. I went from rummaging about in bins to rummaging around in archives, ultimately unearthing a largely forgotten piece of World War II history.

The London Blitz, 9 September 1940.

A well-timed treatment

Rescuing Louden’s obituary from beneath a pile of discarded building material turned out to be eerily apt. The newspaper’s brief account of her life revealed she had helped develop a treatment for ‘crush syndrome’, a condition that afflicted patients dug out from bombed buildings during the Blitz.

People suffering from crush syndrome were extricated from their homes and, unlike the buildings they were removed from, they appeared unharmed. But then, a few days later, they would suddenly collapse and die of what appeared to be uraemia, a build-up of toxins in the blood that are normally eliminated in urine.

During World War II, Louden was working for the South London Hospital for Women and Children (SLHWC) and witnessed this phenomenon occurring numerous times. It was a mystery, but one that had already been identified by doctors in Germany, who had experience of crush syndrome from World War I. Because information was not shared, research into the condition was still in its infancy.

In 1941, a medical team including the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, who was working as a mortuary porter at Guy’s Hospital at the time, was sent to Newcastle to investigate civilian industrial accidents. They discovered that blood and fluids should be replaced in crush victims. This led to the Ministry of Health advising, in 1943, that sodium bicarbonate should be administered to people who had been crushed.

However, the solution was always drunk too late. But then, a year later, Louden gave a pint and a half of the fluid to a crush victim before she was dug out. Once in hospital, the woman’s leg swelled, but the early intake of fluids ensured that the build-up of myoglobin was gradually passed in her urine rather than overwhelming the kidneys.

By the end of the war the woman had recovered. Louden’s method had been a success, and sodium bicarbonate solution started being used to treat renal failure, too.

Model of the myoglobin protein molecule.

Staying out of the limelight

Louden’s pioneering and well-timed treatment saved people who suffered internal injuries after being crushed by buildings during the Blitz. She was a wartime hero, so why have her deeds gone largely untold until now?

When I tried to find out more about her online, there was hardly any information and the one book briefly detailing her life, ‘The Fellowship of Women’ by Margaret Ghilchik, was now out of print. I thought I might be able to piece together Louden’s life by visiting archives and speaking to the institutions she once was a part of. Then I could create a Wikipedia page for the pioneer I’d found languishing in a neighbour’s bin.

Maybe it was modesty that meant her research into crush syndrome was never published, although Ghilchik claims she was “very confident in her ability as a young doctor”. In fact, the research is only mentioned briefly in an article in the British Medical Journal. After reading many of Louden’s notes held in the London Metropolitan Archives, it certainly seems to me that she always put her profession before personal acclaim.

Uncovering Louden’s story

Louden’s school records – she attended St Paul’s Girls’ School from 1924 to 1928 – suggest she was an independent, progressive spirit: she opposed a debating motion that claimed England had benefited from the Industrial Revolution. Howard Bailes, once a history teacher at the school and now its part-time archivist, revealed that she was both academic and talented at sport, captaining cricket and swimming teams.

In 1928, Louden enrolled at the London School of Medicine and six years later qualified as a surgeon. She became a fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons in 1938. After working as a registrar at Guy’s Hospital, she became a consultant at SLHWC, which was staffed only by women doctors. She worked there until 1975.

Margaret Louden's obituary in the Daily Telegraph, 19 February 1999.

Photos from Louden’s leaving party, held in the London Metropolitan Archives, show how multicultural the NHS was and how well liked Louden was, as many workers attended. It was with great sadness that she saw the hospital close in 1984, when she was in retirement, something she had done so much to prevent through campaigns and petitions.

Records show Louden had worked to ensure SLHWC was improved in a way that benefited hospital staff and patients. She was dedicated to the NHS and should be remembered for having been a servant for the great institution.

Also in the archives are images of Louden, dating from 1944, when she was photographed demonstrating how to cook an omelette for the Evening Standard. A brusque note attached to these photos reads: “this picture appeared under the false caption that ‘woman surgeon says operating is easier than making omelettes’”.

I gulped when I read that note, as it seemed like she might have been a hard person to please. But after months and months of research, I hope that if she were alive today she would realise that I’ve done my best to uncover the story of the great woman I found in a bin.

Because excavating Margaret Louden is the least I can do, considering the role she played during World War II and in the establishment of the NHS. And the journey I took to discover her life – from bin, to writing this essay and creating a Wikipedia page for her – gave my life the variety it sorely needed during lockdown.

About the contributors

David Jesudason

David Jesudason is a freelance journalist who covers race issues for BBC Culture, Pellicle and Vittles. He was named Beer Writer of the Year in 2023, after his first book ‘Desi Pubs, A Guide to British-Indian Pubs, Food and Culture’ was hailed as “the most important volume on pubs in 50 years”. David also writes ‘Pub Episodes of My Life’, a weekly newsletter about the drinking establishments that serve marginalised people.

Steven Pocock

Steven is a photographer at Wellcome. His photography takes inspiration from the museum’s rich and varied collections. He enjoys collaborating on creative projects and taking them to imaginative places.