Artist Amanda Couch was drawn to the medieval folding almanac by both its form and content. Its entrail-like folds and the act of divination that linked the movement of the stars to health resonated with her own practice, connecting the bodily process of digestion with everyday living. Her response was ‘Huwawa in the Everyday: An Almanac’, an artist’s book designed to be worn and used to rethink our relationship with the world around us.

Divining the world through an artist’s almanac

Words and artworks by Amanda Couchaverage reading time 3 minutes

- Article

My artist book, ‘Huwawa in the Everyday: An Almanac’ mimics the utilitarian function of a medieval folding almanac, bidding us to attend to our body’s interconnected relationship with the world.

Medieval folding almanacs, also known as girdlebooks, were portable collections of manuscripts used by physicians to prognosticate and diagnose. Hung from the waist, they contained calendrical, astrological and medical information. Their combination of charts with the calculations of astrological movements, lists of feast days and corporeal diagrams connected parts of the body with their corresponding astrological signs, as well as other texts.

The 15th-century medieval almanac being unfolded to reveal astrological charts and a ‘Zodiac Man’, linking the body to signs of the horoscope.

Historian Hilary Carey argues that the practice of astrology was at the heart of medieval medicine, and that medical treatments would have been guided by astrological knowledge and interpretation of the position of the celestial bodies at particular times.

Divination and diagnosis

While not directly illustrating medical or astrological information, ‘Huwawa in the Everyday’ draws on the art of divination – the practice of seeking to foretell future events or discover hidden knowledge by the interpretation of signs and omens. In ancient times, the two most common forms of divination – astrology: divination using the stars and planets, and extispicy: divination using animal entrails – drew on each other to relate the cosmic realm to the human body.

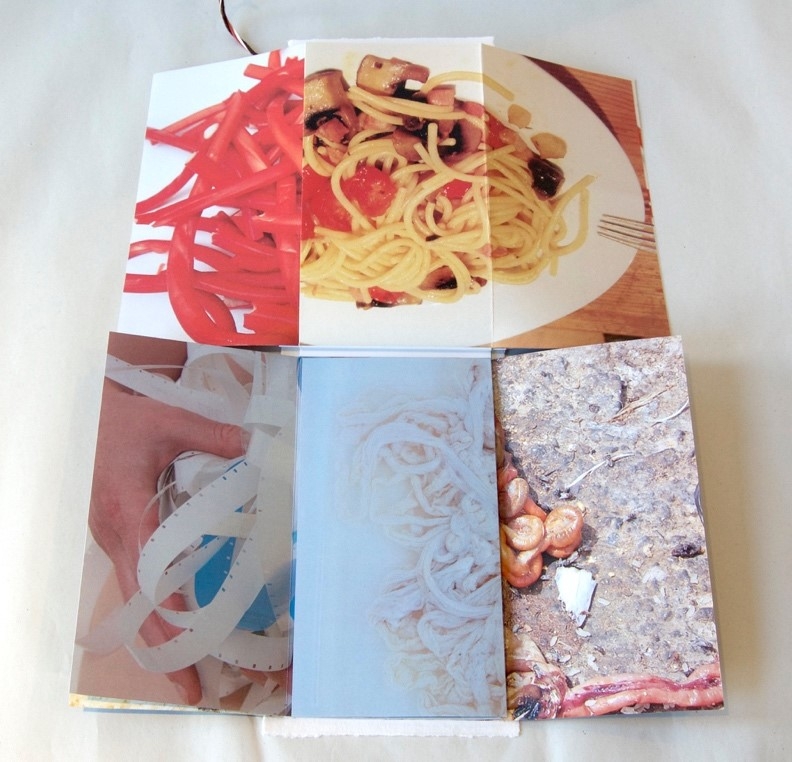

Unfolded leaves from ‘Huwawa in the Everyday’, showing photographs of entangled spaghetti, paper strips, sausage skin and entrails.

‘Huwawa in the Everyday’ is a photobook of twelve images, one for each of the houses that divide the horoscope. These images depict actual guts, or coiled materials resembling intestines that are encountered in the everyday. The book asks us to recognise that the inside of our body and the external world are interrelated and part of the same whole.

The photographs spotlight that the alimentary canal is both inside the body and also a tube that runs through it, connected to the external environment.

Huwawa the ecowarrior

The title and cover image of my almanac refer to Huwawa (also known as Humbaba), a giant slain by Gilgamesh in ancient Mesopotamian mythology. The cover image is the face of Huwawa as represented on a Babylonian clay tablet held by the British Museum, but the image is additionally described as the record of an actual examination of sheep intestines. On the reverse of the tablet, the inscription reveals that if someone seeking answers saw this pattern in the entrails, they would have “dominion over the land”. Scholars interpreted this as foretelling revolution.

The Babylonian clay tablet/mask of Huwawa (Humbaba), 2000 BCE–1600 BCE.

Huwawa appears in the ‘Epic of Gilgamesh’, the ancient Mesopotamian poem, which is considered to be the earliest surviving example of literature. Described as a monster, Huwawa was appointed by the god Enlil as protector of the Cedar Forest. Through trickery and deception, he was killed by Gilgamesh and Enkidu, who then proceeded to fell the trees in what could arguably be interpreted as the first recorded act of environmental desecration.

And perhaps this is what draws me. Could it be that by seeking to divine Huwawa in the everyday ‘entrails’ of the world around us, I am hoping for signs of a revolution that might be the only path left to halt and reverse the devastating effects of climate change, mass species extinction and habitat loss?

Out in the world with ‘Huwawa in the Everyday' at your waist.

Understanding my place in the world

‘Huwawa in the Everyday: An Almanac’ could be classified as what artist and theorist Johanna Drucker calls “book as performance”. Rather than simply reading the book, the beholder becomes the performer and enacts the book by using it as prompt to notice entrails in the world. They are also simultaneously brought back to connect to their belly and intestines through the wearing of the book from the waist.

Another term for a folding almanac is vade mecum, meaning ‘come with me’. As I wander, with my own version of a vade mecum, the book guides me to cultivate mindful awareness in my surroundings, particularly alleviating anxiety associated with obsessive and repetitive thoughts that I sometimes experience.

Akin to how medieval almanacs were used identify and treat illness by observing the planetary signs, these practices enable me to ‘diagnose’ as in the original sense of the meaning of the word: from dia-gnosis, meaning ‘to learn’ so I am better able to come to know the world and my place within it.

And the sharpening of our sensitivity to intestinal materials and forms enables a dissolving of hierarchies of self and other, and the boundaries of inside and outside, allowing us space for a radical rethinking of our relationship with the world.

About the author

Amanda Couch

Amanda Couch is an award-winning artist, researcher and senior lecturer whose practices cut across media: performance, sculpture, photography, print and the book, food, the everyday, participation, and writing to research and reimagine histories of the body.