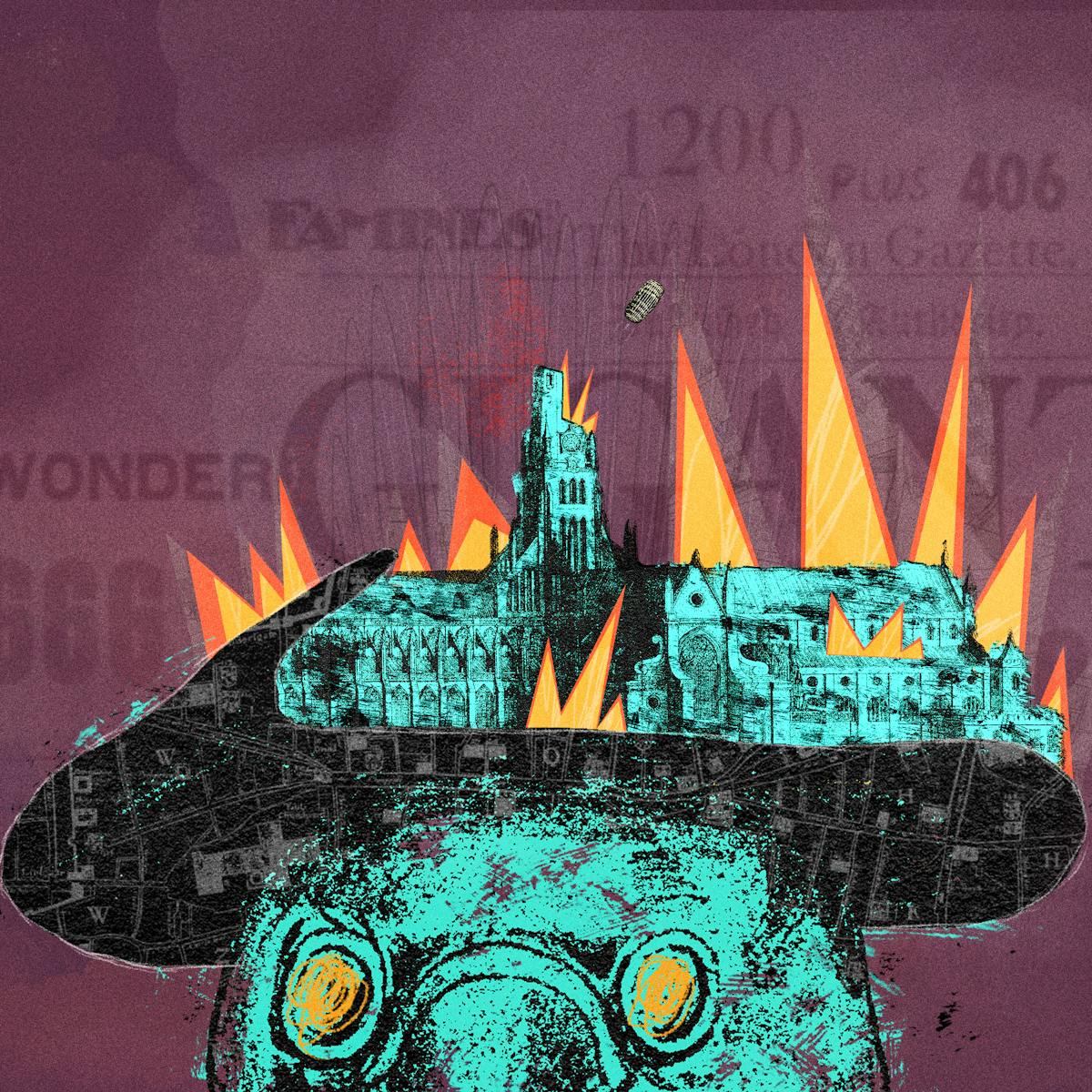

Calculations abounded to show why the year 1666 could herald the end of the world or, alternatively, the return of Jesus and the establishment of heaven on Earth. As Europe sweated under the plague, fevered imaginations turned to the future, generating a flurry of inventions and technological advancements.

Devilry and doom in 1666

Words by Charlotte Sleighartwork by Gergo Vargaaverage reading time 6 minutes

- Serial

It was 1666, and the great city of London burning was, it seemed, yet another sign that the end of days was here. Albrecht Dürer’s ‘Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse’ (1498) included Death, Famine, War and Plague, and by the middle of the 17th century there had been plenty of all four in Europe. Catholics and Protestants, and their royal proxies, had slaughtered one another around Europe, and bubonic fleas crawled from body to body as fast as heresy could be whispered.

As if things were not already bad enough, 1666 was an ominous date for Christians, comprising a millennium since Christ appeared on earth and the mysterious “number of the beast”, 666, both prophesied in the final book of the Bible, Revelation. Such an apocalyptic omen, coming amidst death and chaos of every kind, spawned thousands of pamphlets and speculations.

The writer and natural philosopher (scientist) John Evelyn read them with a mixture of fascination, scepticism and consternation; this was to be “a Year of Wonders, of strange Revolutions in the World”.

From the streets to the Second Coming

The exact calculation and the ordering of the millennium and the apocalypse were open to debate. In 1660, an anonymous writer going by the alias “Friend to the Truth” produced a complex calculation and explanation as to why the “Egge of Antichristianisme” would hatch its devilish beast in 1666. In just six years’ time God’s wrath would be unleashed upon the Earth in order to destroy the ghastly creature.

The London barrel-maker Thomas Venner prayed most earnestly for that year to dawn. He was a leader of the Fifth Monarchy Men, a follower of the biblical prophecy of a last, holy king to come after four ungodly ones. The message was clear for Venner and his followers: King Jesus was to replace Charles I. Even Cromwell – whose megalomania made him a self-crowned king – stood between history and the proper coronation of the Lord.

The Jews would be restored to Zion, and “wicked empires” in Rome and Babylon destroyed, all through an armed insurrection that started – and ended – in the streets and pubs around St Paul’s Cathedral. What happened on the streets of London had significance for the fate of the Earth – the very cosmos.

“It was 1666, and the great city of London burning was, it seemed, yet another sign that the end of days was here.”

Imagining the new world

Apocalyptic and mystical cults flourished as the pamphlets and buboes spread, but so did science and invention. Perhaps unexpectedly, much scientific development during this time was also premised on a desire to bring about the Divine closure of history. Founders of the Royal Society of London – the pioneering academy of science – believed that the millennium would be marked, or accomplished, by advancing human knowledge to a godlike level.

Samuel Hartlib was one of these, a Polish emigré whose thirst for knowledge drank up agriculture, weaponry and more. Hartlib also dreamed of the end of humanity as his neighbours knew it. He pledged himself to a secret fraternity of like-minded men; together they aimed to reconcile all warring Protestant factions and start a utopian scientific community on a Baltic island.

He was fascinated by the “commonwealth” of bees, perhaps a model of the heavenly city that closes the book of Revelation. By helping to spread intelligence of the latest natural philosophy (science), Hartlib aimed to bring heaven on Earth.

While the Fifth Monarchy Men relished the prospect of violence and revolution to bring on the millennium of God’s kingdom, men of science in general did not. The fabulously wealthy natural philosopher Robert Boyle, in particular, had a great deal to lose if the world were “turn’d upside down”. He sloped into radical meetings to find out what the plotters were saying, on one occasion leaping to his feet to correct the “depraved” interpretation of the Old Testament that he heard offered as a vindication of revolution.

Boyle, a fellow founder of the Royal Society, was no less anxious than the radicals to see the millennium of Christ’s rule come. Unlike these, however, he saw the birth of the new age as comparatively easy, and something that would, moreover, leave his position untouched. Nor was there any need, as Hartlib thought, to escape to a distant isle to find it.

Boyle scribbled down a feverish list of discoveries that, if accomplished, would show that humans had attained a heavenly kingdom on Earth. “Attaining Gigantick Dimensions” was one ambition; so too were flying through the air and moving underwater. His precise ambitions look odd by today’s standards; perhaps they replicated the powers of angels (flying) or transcending the limits of earthly bodies.

“Albrecht Dürer’s ‘Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse’ (1498) included Death, Famine, War and Plague, and by the middle of the 17th century there had been plenty of all four in Europe.”

The most striking of Boyle’s ambitions promised to undo the curse of humanity’s Fall. According to the book of Genesis, humans were cursed with hard work, with limits to their knowledge and, ultimately, mortality. Boyle looked to reverse the punishments: for tools to ease human labour, and for “Potent Druggs to alter or Exalt Imagination [and] Memory” to correct lapsed intellectual powers.

He even looked for “the recovery of youth” and “the Prolongation of life”. This set of ambitions, and its millennial purposes, helped to bond and motivate the members of the new Royal Society that grew from Hartlib and Boyle’s circle.

Big dreams for a broken system

Sociologists often refer to such combined social and technological inspirations for a desired world as ‘imaginaries’. Natural philosophers imagined both the type of world they wanted to live in (a godly one), and the types of science and technology that would enable and define such a world.

The combination spurred them on to extraordinary achievements. Hartlib and Boyle did not attain the power of flight (at least, not at once) but, fired by the power of imagination, they met many of their other goals. By developing telescopes, microscopes, and social norms for agreeing and disseminating their findings, they did indeed extend the limits of knowledge and lessen – for a lucky minority – the grind of labour.

For Hartlib and Boyle, creating a shared ‘imaginary’ was a matter of responding to a crisis about theology and government. Today, the pressing task is one of creating an imaginary for a shared climate future.

Many technologies that have been proposed as solutions implicate imaginaries that continue to embed capitalist inequalities. Carbon capture – an as-yet-imaginary technology at scale – is nothing more than a sticking plaster for a broken system, a clean-up mechanism that will enable business as usual. (Despite its unproven status, the British government's decarbonisation strategy relies upon it.)

Our millennial predecessors had a huge framework of theology around which to construct their scientific dreams. Perhaps before we dream up new pieces of planet-fixing tech, we need first to find an equally compelling spiritual or philosophical framework for our imaginary – and one that puts climate justice and the intrinsic value of nature at its centre.

About the contributors

Charlotte Sleigh

Charlotte Sleigh is an interdisciplinary writer and practitioner in the science humanities. Her most recent book is ‘Human’ (Reaktion, 2020). She is Honorary Professor at the Department of Science and Technology Studies, UCL, and current president of the British Society for the History of Science.

Gergo Varga

Gergo Varga is an illustrator, collage animator, motion designer and the name behind ‘varrgo’. varrgo is a place where Gergo creates and animates mixed-media projects, particularly in the style of collages and cut-outs. He enjoys working with things that have already had a life, from old magazines to scribbles in a notebook. His longest-running creative project is ‘oners’, where he visualises one-minute quotes from contemporary thinkers. Gergo created the animations and illustrations for ‘Apocalypse How?’ and ‘Eugenics and Other Stories’, published on Wellcome Collection Stories.