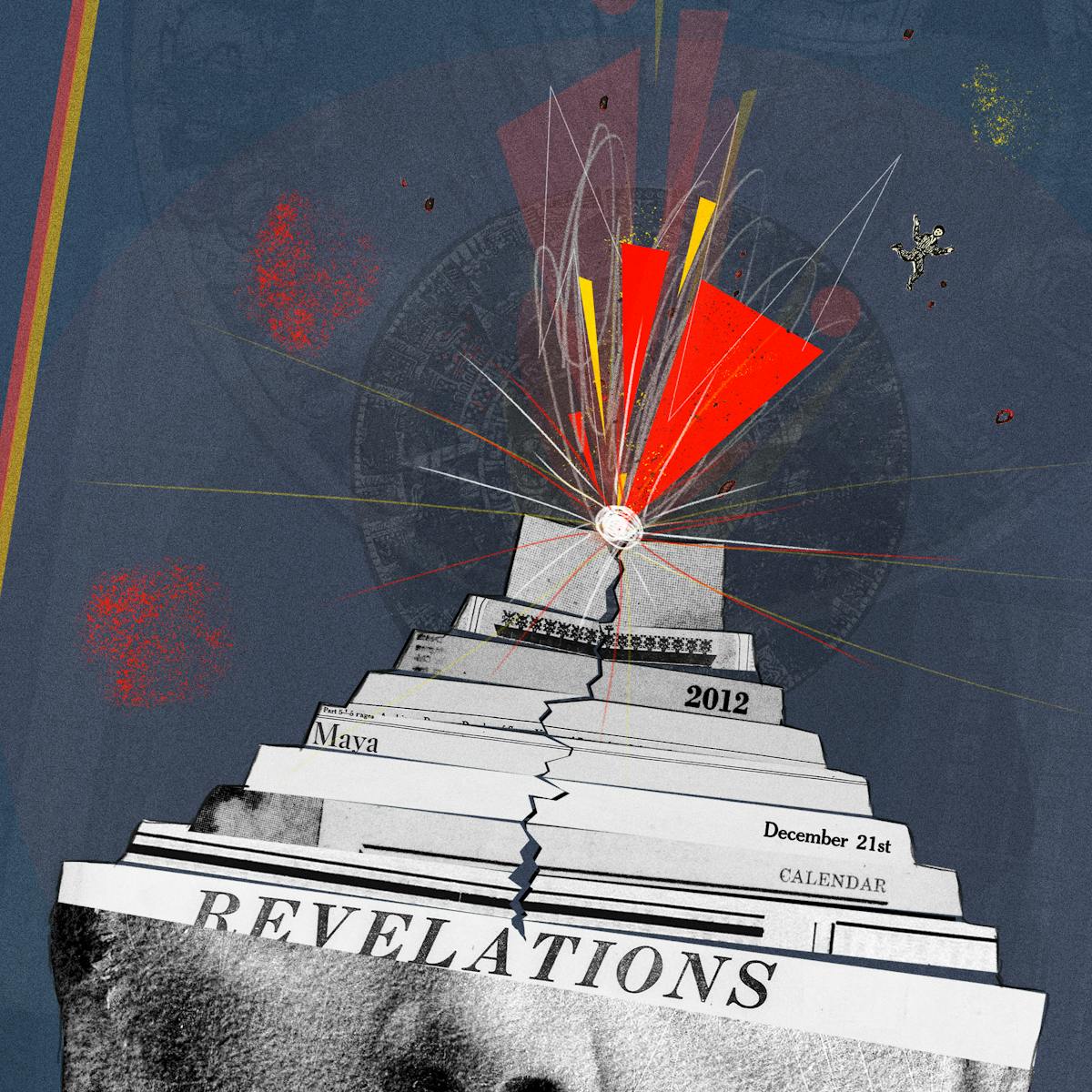

For centuries, humans have anticipated their own extinction. Although the Christian apocalypse brings life on Earth to a close, other cultures, such as the Maya, have included a new beginning in the end, creating cyclical rather than linear calendars. Historian Charlotte Sleigh examines why the end, periodically, seems nigh, and what we can learn from past predictions.

Deciding a date for the end of the world

Words by Charlotte Sleighartwork by Gergo Vargaaverage reading time 6 minutes

- Serial

In 2017, the highly respected Scripps Institution of Oceanography gave humans a 5 per cent chance of extinction by the century’s end. Scripps put a figure on the swirling fears related to climate change, the reasonable but as then unquantified risk that we might bring about our own demise.

It wasn’t the first time that people had thought about their own end. For many hundreds of years, we have projected an imminent termination to our world, whether through the capriciousness of the gods or as a result of our own actions.

This series will look at previous prophecies and sciences of annihilation, asking what we can learn from these curious episodes. Why did the end seem nigh, and how did people respond in each of these moments? Climate change is different from the subjects of those false alarms, but with the benefit of their history, we might approach the brink a little more wisely this time.

The end...

For those of us living in the West, the Christian religion has been largely responsible for shaping our expectations of the end of the world. Christians are told to think and act with their final reckoning in mind. St Paul advised the Corinthians: “[T]he time is short. From now on... those who buy something, [should live] as if it were not theirs to keep.”

At the Christian apocalypse, Christ will return and take the faithful with him to heaven, while sinners are condemned to hell. This prophecy is recorded in the Book of Revelation, one of 66 texts that were compiled around 400 CE to form the complete Bible.

Bound books were an innovation at this time, and they went together well with a religion that was uniquely premised upon a linear time structure, from Creation to Fall, salvation to judgement. At the book’s end, Revelation narrated the closure of all earthly things. History now had a last page, waiting to be revealed before the clapping shut of the covers: “The End.”

“Cyclic calendars – loops of time of different lengths that came in and out of synchronisation – were the norm in ancient and early modern Mesoamerica.”

... or a bloody fresh start?

But there is, in principle, no need for the apocalypse to be a last-page, final event. Time, in many cultures, is cyclic: after the end of the world comes a fresh beginning.

One of the key Maya calendars was a round of 7,200 days. In the epic prophecy ‘Cuceb’ (“that which revolves”), Katun was a god who embodied the era. When he began to limp, as scholar John Bierhorst explains, it was time to find a human surrogate. This person had to be tortured or even killed to make way for the next era.

Cyclic calendars – loops of time of different lengths that came in and out of synchronisation – were the norm in ancient and early modern Mesoamerica. The sacred tzolkʼin cycle of 260 days combined with the solar year, the haab’, to produce a long calendar round that resets every 52 years. One round of the long calendar was not far off life expectancy for a Mayan or a Zapotec. The end of the calendar might be the end of the world for someone whose life matched its beginning and end, but everyone else would carry on.

Appropriately enough, the codices on which the Mayans recorded their calendars were not bound as books, with their linear narrative, but folded out on giant sheets of bark-based paper. They burned easily when the Europeans consigned them, all but four, to the flames.

World without end

Although Christians ostensibly believed in an apocalypse, fewer than three centuries after decimating the ‘primitive’ Mesoamericans, European settlers developed their own mythological time system that imagined a world without end. It was called the futures market, and from the latter half of the 19th century, it dominated US trade in agricultural and other goods.

Capitalism depends upon everyone committing to imagining the future, and not just any kind of future, but a cheery, business-as-usual future. The promise of future profit, built on debt in the present, demands it. Trades in ‘futures’ promised prices for commodities that had yet to even be produced or delivered. St Paul would most certainly have disapproved.

“Goodman began tying to synchronise Mayan calendars to the modern, Western one. What was the zero point of Mesoamerican time?”

Joseph T Goodman was caught between the heritage of Christ and capital. As a successful newspaper editor in 19th-century Nevada, he helped create the accelerated flow of information that bred the futures markets. Upon giving up the paper, Goodman went into the heart of capital, taking up a seat on the Pacific Stock Exchange and becoming a successful trader and investor. So far so futurist.

But at the same time, Goodman became obsessed with Mayan calendars. He learned that a non-repeating ‘long count’ had been in use before the European invasion, providing a historical dating system (used on monuments) that was anchored in a creation event.

Goodman began trying to synchronise this calendar to the modern, Western one. What was the zero point of Mesoamerican time?

The apocalypse of 2012

Goodman eventually figured out an answer. No matter that the Maya were unlikely to have thought of time’s start in the literal way that 20th-century Americans did. He pinpointed the start date for the Mayan calendar as 11 August 3114 BCE. The book of Western mythology had a new first page, based in American cultures, and calculated by science.

This first page inevitably invited a last page: a moment of ending. New Agers and conspiracy theorists counted forwards to find the end of the world. The end-date of a 5,126-year-long cycle in the Mesoamerican Long Count calendar was 21 December 2012.

Despite the specific, carefully calculated date, people could not agree upon the details of how the apocalypse would happen. Explanations read like a list of science-fiction disaster films: depending on whether you studied Ancient Egyptians or Mayans, or relied on your own hallucinogenic revelations, it might come in the form of a disastrous reversal of the Earth’s magnetic field, a planetary collision, or a supermassive black hole.

The believers had missed the point. Just as Goodman never reconciled his desire to pinpoint “the end” with a career predicated on the end never coming, perhaps it was less painful to deflect their attention away from reality and towards alien conspiracy theories instead.

By the time 2012 rolled around, the world had already gone through one of its periodic financial Cucebs. The global banking meltdown of 2008 had sacrificed the world’s poorest and most climate-vulnerable in schemes of ‘austerity’ to restart the cycle of profit. Meanwhile, the planet grew hotter and hotter. It was apparently harder to imagine getting rid of capitalism than it was to imagine the end of the world itself.

About the contributors

Charlotte Sleigh

Charlotte Sleigh is an interdisciplinary writer and practitioner in the science humanities. Her most recent book is ‘Human’ (Reaktion, 2020). She is Honorary Professor at the Department of Science and Technology Studies, UCL, and current president of the British Society for the History of Science.

Gergo Varga

Gergo Varga is an illustrator, collage animator, motion designer and the name behind ‘varrgo’. varrgo is a place where Gergo creates and animates mixed-media projects, particularly in the style of collages and cut-outs. He enjoys working with things that have already had a life, from old magazines to scribbles in a notebook. His longest-running creative project is ‘oners’, where he visualises one-minute quotes from contemporary thinkers. Gergo created the animations and illustrations for ‘Apocalypse How?’ and ‘Eugenics and Other Stories’, published on Wellcome Collection Stories.