In ‘The Story of the Brain in 10½ Cells’, neuroscientist Richard Wingate invites readers to fall in love with the beauty of the brain. By examining brain cells under the microscope, it’s possible to glimpse the hidden architecture behind everything that we think and feel. Here, in an abridged extract from the book, Richard recalls what it was like to see a brain cell for the first time and reflects on the magical moment when early brain pioneer Santiago Ramón y Cajal witnessed the same.

If thought has shape, what does it look like? My first brain cell was bright fluorescent yellow – made so by a dye, Lucifer yellow, that I had injected into its fleshy centre using a vanishingly small glass tube.

I had been randomly probing brain fragments, carefully dissected into dishes and placed under a microscope, with a glass rod pulled into a fine point in a miniature forge.

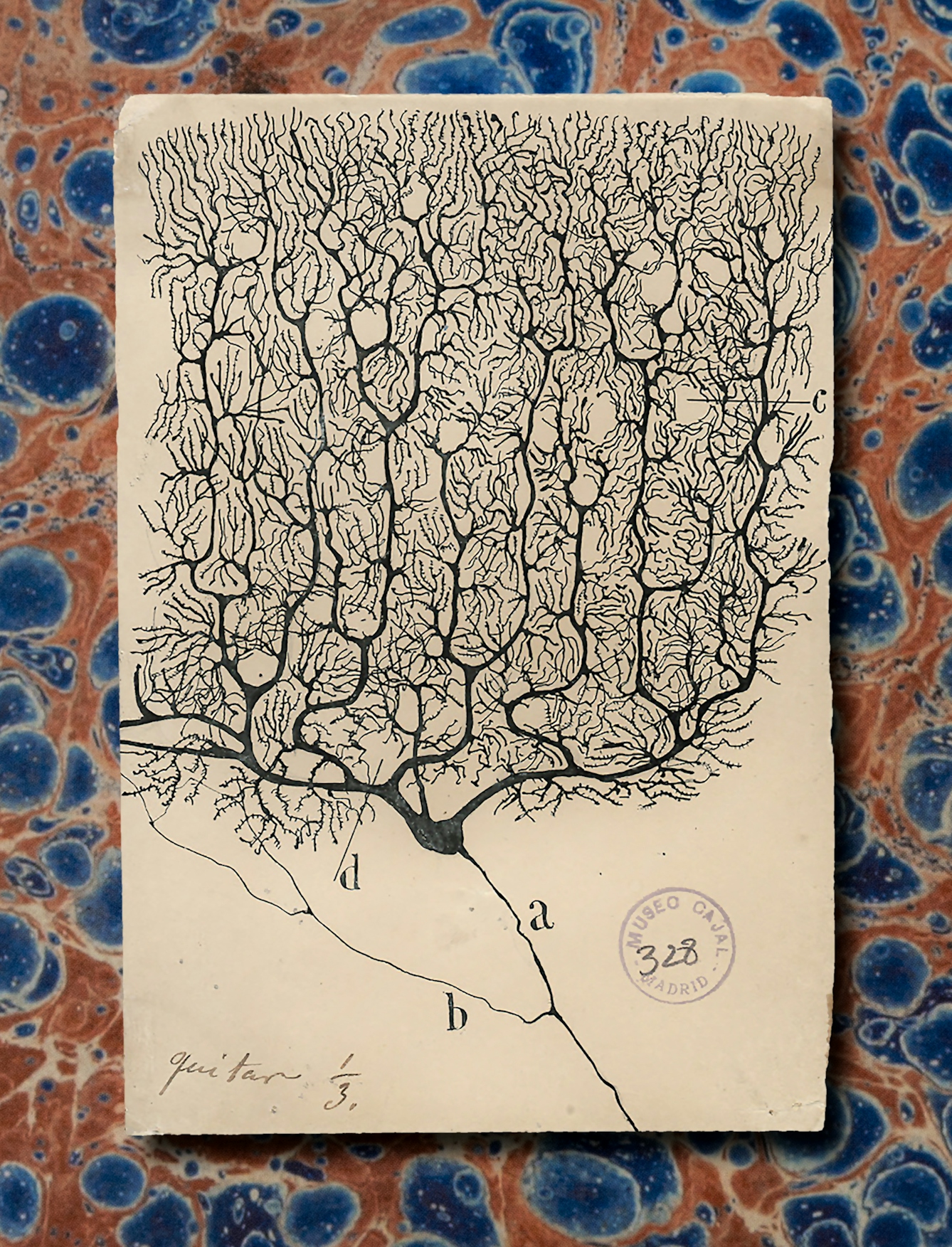

Suddenly, after what seemed like months of attempts, the sharp glass needle hit the invisible centre of a brain cell, penetrated its thin membrane – without, for once, tearing a gaping hole – and the dye, contained and bright, flowed outwards into the taut sphere that is the cell’s body and then into its elaborate, tree-like arms.

I watched it fill rapidly with colour. First the thick branches, which then split, and divided again into twisting tendrils until the smallest and most delicate twigs glowed.

I flicked my wrist on a metal dial to pull the glass needle away from the cell and stared through the two eyepieces of the microscope down to the square millimetre of brain, 20 centimetres below and separated from my eyes by 20 or more stages of optically engineered glass.

Near darkness. The room faintly illuminated by the reflected intense blue light emanating from an ultraviolet bulb caged in its metal housing. There was a humming from the electronics to my right, the faint smell of mechanical oil from the dials, shutters and switches on my microscope. The cell was symmetrical, beautiful, perfect.

A life-changing revelation

There is a passage written by one of the early brain pioneers, Santiago Ramón y Cajal (1852–1934), that almost invariably moves me to tears. I use the quote in lectures to students quite often. It illustrates a landmark moment in the science of the brain and also a moment of personal revelation. It’s the beautifully articulated instant in time when everything changes; for the brain, for Cajal himself.

“First the thick branches, which then split, and divided again into twisting tendrils until the smallest and most delicate twigs glowed.”

But as important as it is as a moment for science and for an unlikely scientific genius from a dusty and impoverished mountainside village, I still can’t work out why it makes me cry, and it has become a private joke with myself – a test. I make the point of reading it aloud whenever I can to a class. However hard I try, I hear the crack in my voice, a hoarseness in my throat and I have to turn away from the audience to read from the projector screen, hiding the emotion as best I can. I don’t think anyone has noticed yet. And however often I test myself, the result is the same.

The passage marks a moment of revelation that is a turning point for science – the start of one man’s remarkable crusade to understand the brain through its brain cells but also a launchpad for a thousand more careers. Cajal was not the first person to look at the microscopic form of the brain, but his ability to empathise with what he saw and the imagination he brought to its understanding stood out among his peers.

Cajal was not the first person to look at the microscopic form of the brain, but his ability to empathise with what he saw stood out among his peers.

In 1887 Cajal was invited to sit on an interview panel for candidate anatomy teachers in Madrid. He took the opportunity to visit colleagues in what can best be described as an informal biology ‘salon’ – a hobbyist’s laboratory that, like Cajal’s own laboratory in Zaragoza, had been squeezed into a house in Calle de la Gorguera 1, a few steps from the Plaza de Santa Ana.

This was an era in Spain when the idea of conducting research that could be written about or published in journals was a seemingly impossible dream to Cajal. Exploration of this kind was certainly not part of the Spanish anatomist’s day job. In the salon, ideas could be discussed and experiments conducted away from the formal corridors of the medical school. The excitement was infectious.

It was in this clubhouse atmosphere that Cajal met Luis Simarro, a neurologist who had only recently returned from Paris and who was fired up with enthusiasm for the new research he had seen. Better still, he had brought back some of the material that he had encountered in his travels. Simarro invited Cajal back to his own home, and his private microscope, to show him some of the treasures that he had gathered.

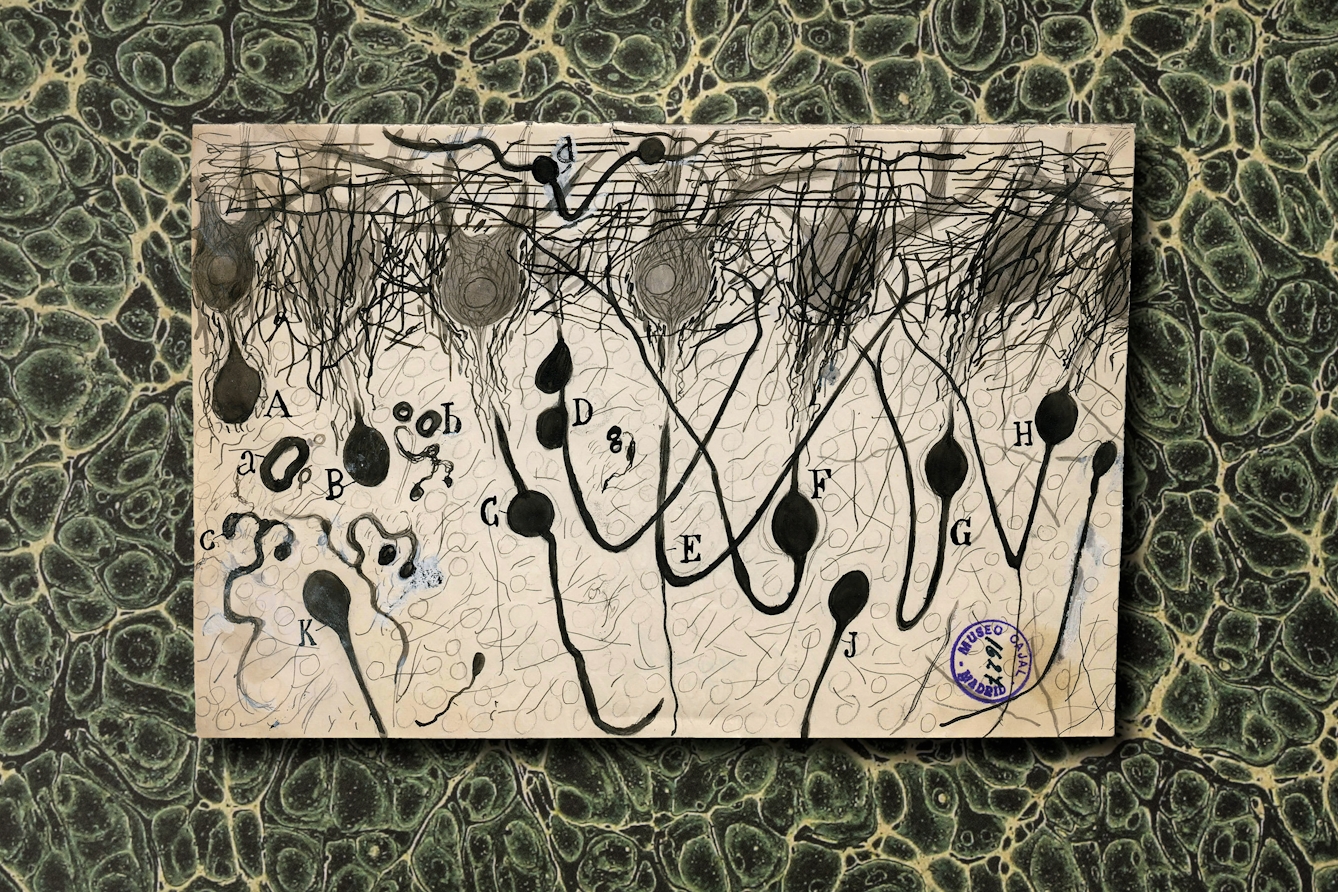

Among the samples, brightly coloured, glued with gum to slides, cut into thin or thick slices, one blackened lump of brain stood out. It was prepared using a technique invented in Pavia by Camillo Golgi. Simarro even had a rare copy of some of the drawings its inventor had made and recipes for the technique published in a memoir just one year before.

What Cajal saw next in Simarro’s back-room laboratory changed his life. He could not sleep that night and early the next morning he was knocking again on Simarro’s front door to beg another look at a lump of brain chemically treated with what became known as the Golgi stain.

“Among the samples, brightly coloured, glued with gum to slides, cut into thin or thick slices, one blackened lump of brain stood out.”

“Against a clear background stood black threadlets, some slender and smooth, some thick and thorny, in a pattern punctuated by small dense spots, stellate or fusiform. All was sharp as a sketch with Chinese ink on transparent Japan-paper. And to think that that was the same tissue which when stained with carmine or logwood left the eye in a tangled thicket where sight may stare and grope ever fruitlessly, baffled in its effort to unravel confusion and lost for ever in a twilit doubt. Here on the contrary, all was clear and plain as a diagram. A look was enough. Dumbfounded, I could not take my eye from the microscope.”

The words sound fresh to my ears, and the experience of being dumbfounded, the jaw dropping, the blink to look again. That is the moment when you realise that here is something new, never seen before or seen by only a few.

The beauty of brain cells

My jaw dropped when I saw my first brain cell emerging from the dark. It looked like rivers of molten metal being poured into a mould. That time I was frozen in awe, while other times I’ve jumped up and punched the air or paced the room trying to contain myself before looking again to make sure.

These moments make up the best parts of science. Years of failed experiments can be forgotten in a moment. So Cajal’s words reach into that part of me that makes me want to go back again and again to the raw excitement of discovery.

But there was more to this than just an excitement at a new tool or a glimpse of what next month’s project might be at home in his own back-room lab. What Cajal witnessed in the house on Calle del Arco de Santa Maria was an answer, or rather the roadmap to an answer of the riddle of the brain itself.

This was the dramatic and sudden unveiling of its architecture – a diagram that was yet without meaning, but for the first time, a richly filled canvas with structure and signposts. Cajal knew that the brain and its secrets were there for the taking. He returned home to Zaragoza and set off on a journey of discovery that changed his life and established the foundation of a science of the brain.

“My jaw dropped when I saw my first brain cell emerging from the dark. It looked like rivers of molten metal being poured into a mould.”

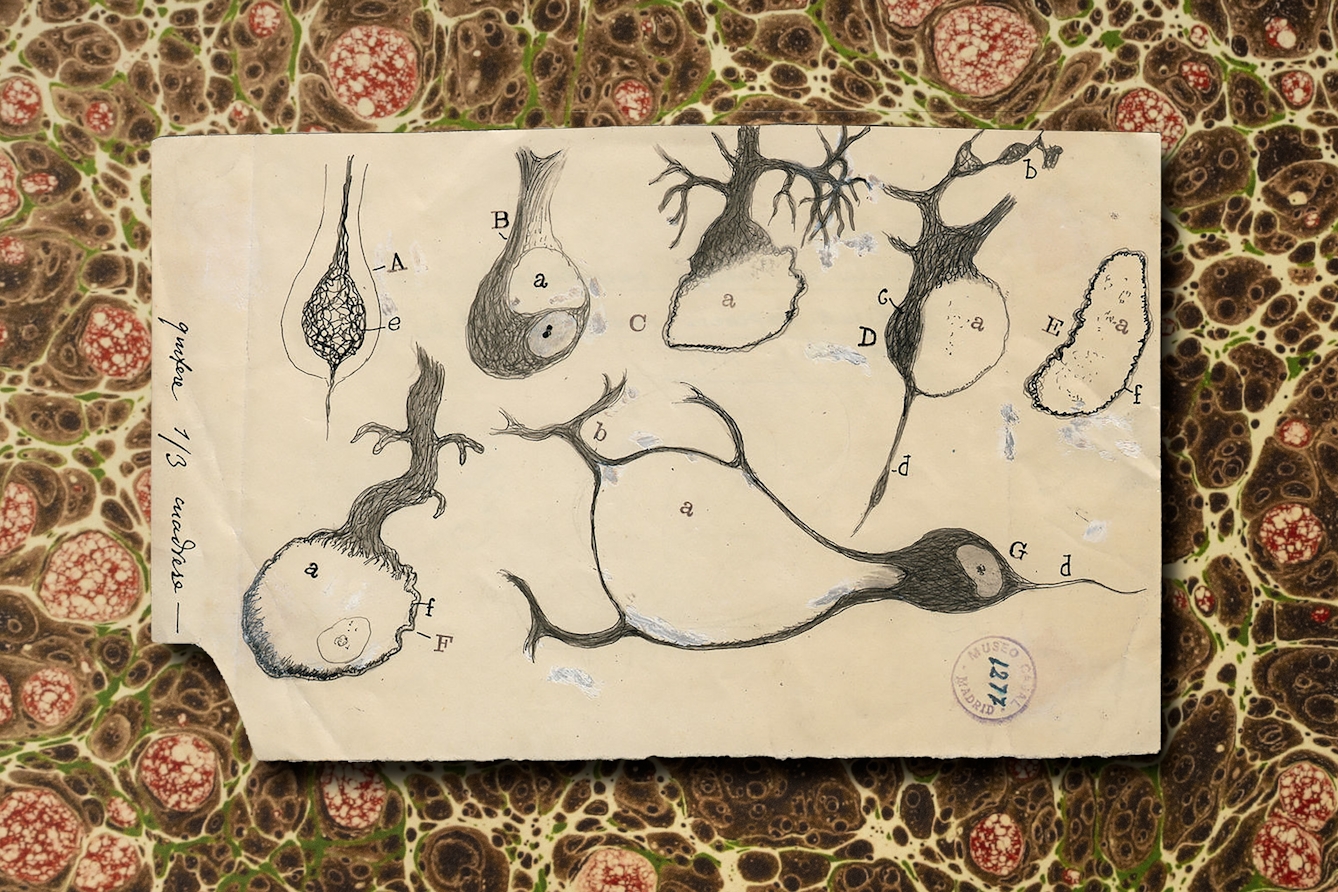

Brain cells are beautiful. They are compelling and varied in the same way that trees have a sinuous and emotional beauty. Trees have a form that speaks of their fight against gravity and wind to stretch into the light and grow. Brain cells have an identical, purposeful form, but their nature and their variety have a purpose that we don’t fully understand.

The brain cell is the stuff from which the brain’s function is built. Its shape is nothing less than the physical manifestation of a fragment of thought. This was the realisation that stopped Cajal in his tracks. There, sitting at Luis Simarro’s microscope, what sprang out of the blackened, dehydrated brain, drenched in silver and osmium, was a glimpse of the hidden language of all that we think and feel.

He had imagined this moment before, in Zaragoza, as he had experimented and dissected, teased with forceps, dipped and stained tissue through one solution after another. But he never dreamed it would be like this: so clear, so sharply etched. Here was a pattern, a structure, wonderful and mysterious and pregnant with meaning waiting to be uncovered. All he needed to do was to look.

‘The Story of the Brain in 10½ Cells’ is out now.

About the contributors

Richard Wingate

Richard Wingate is a world-renowned neuroanatomist and neuroscientist. He is principal investigator at the MRC Centre for Neurodevelopmental Disorders, and Professor of Developmental Neurobiology at King’s College London. He is also Editor-in-Chief of brainfacts.org, the highly popular website that celebrates the wonders of the brain, and is supported by the Kavli Foundation, the Gatsby Charitable Foundation, and the Society for Neuroscience.

Steven Pocock

Steven is a photographer at Wellcome. His photography takes inspiration from the museum’s rich and varied collections. He enjoys collaborating on creative projects and taking them to imaginative places.