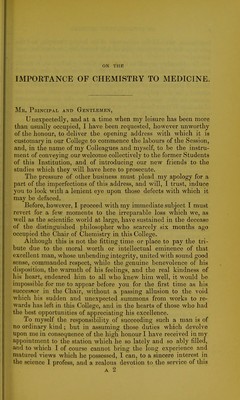

On the importance of chemistry to medicine : an introductory address to the medical classes of King's College, delivered October 1, 1845 : with an inaugural lecture at King's College, given October 6, 1845 / by W. A. Miller.

- Miller, William Allen, 1817-1870.

- Date:

- 1845

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: On the importance of chemistry to medicine : an introductory address to the medical classes of King's College, delivered October 1, 1845 : with an inaugural lecture at King's College, given October 6, 1845 / by W. A. Miller. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by The University of Glasgow Library. The original may be consulted at The University of Glasgow Library.

6/40 (page 6)

![real nature of electricity, of light, of heat, or of any of the won- derful powers by which the changes of the universe are regu- lated and maintained, must be looked upon as an inquiry trau- Bcending our limited endowments. But from the day that modern Chemistry was enabled to demonstrate that the numberless varieties of organized beings which constitute the two grand kingdoms of vegetable and ani- mal life, are composed of materials precisely the same as those which occur abundantly amongst the products of inanimate nature, the discovery of the process by which these lifeless matters become parts of a living organism, and therefore for the time en- dowed with life, has alwaj's been a problem of the highest interest and importance : at the same time that it is one of which the partial solution at least, may reasonably be anticipated. Hitherto we are very far from having attained the end proposed, although we have with certainty discovered some of the mtermediate steps. Our ideas of the direct subservience of vegetable to animal life have increased much in precision, whilst in the constant supply by the animal creation of those substances peculiarly adapted to the support of vegetable life, and which, unless they were sys- tematically and regularly removed from the atmosphere, would accumulate till they destroyed the beings that produced them, we have a most striking display of the harmonious system of compen- sation, which everywhere meets us as the grand principle that pervades the stupendous machinery of the universe. Amongst many striking differences between plants and animals, we may particularly specify two, viz.: First, tne absence of voli- tion in plants, and its presence in animals, intimately connected no doubt with the Second, which is the absence in plants of the rapid and continuous waste and reparation so characteristic of animal life. Plants certainly increase in bulk, they have remark- able powers of assimilation, they are continually putting forth fresh branches, these each returning year are clothed with leaves, which in time fade and decay, to be again renewed; but the removal of matters once deposited, though it does occur in some slight and partial measure, is not a change essential to their existence as it is to that of animals, in whom it is evidenced by the large quan- tities of solid matter they consume as food, whilst their size never increases beyond a limited extent. On the other hand, the con- sumption of food by plants is of so different a description, and of comparatively so small an extent, that for a long time it was almost overlooked; and their growth appears to have no definite boundary. There is no doubt that the nourishment of plants is derived directly from things without life, either suspended in the atmo- s])hcre that surrounds them, or dissolved in the water that pcnc-](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21472865_0006.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)