Copy 1, Volume 1

Hand-book of chemistry / Translated by Henry Watts.

- Gmelin, Leopold, 1788-1853

- Date:

- 1848-1872

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Hand-book of chemistry / Translated by Henry Watts. Source: Wellcome Collection.

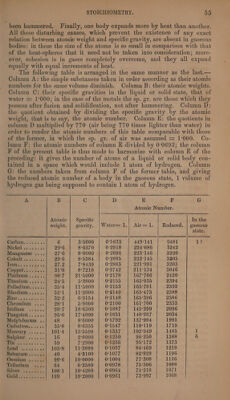

80/562 (page 56)

![A B Cc. D E F eo Atomic Number. Atomic Specific In the weight. | gravity. | Water=1.| Air=1. | Reduced. | gaseous state. ipismntas si. 2. 106°4 9°8220 0°0922 70°994 1024 INV SOTHO) ss Se 75°4 5°9590 0:0792 60°984 880 2 Phosphorus .... 31°4 1°7500 0°0557 42-889 619 2 Antimony ....] 129 6°7010 0°0519 39°963 576 NOON’ 's « Taue « 23°2 0°9722 0°0419 32°263 466 Uranitim; 0.) 27 9:0000 0°0415 31°955 461 ROGUS Ay ar scant 20 4°9480 0°0393 30°261 437 J Bromine 5 sis. 78°4 2°9800 0°0380 29°260 422 1 Chlorine ...... athe | 13333 0°0376 28°952 418 1 Potassium .... 39:2 0°8650 0°0221 17°017 245 By examining this table we arrive at the following results :— 1, Equal volumes of different liquid and solid bodies contain very different numbers of atoms. If1 cubic inch of hydrogen gas contains 1. At. hydrogen, then 1 cub. in. potassium contains 245 . x At. potassium, and 1 cub. in. diamond 6481. At. carbon. Of all liquid and solid bodies potas- sium has the smallest and carbon the greatest (27 times as great) atomic number. This great diversity in the atomic numbers is perhaps to be ex- plained ; (a) from difference of magnitude in the atoms themselyes.—The greater the weight, and therefore also the magnitude of the atoms, the smaller must be the number of them which at equal intervals can be disposed in a given space. This is perhaps one of the causes why uranium which has so large an atomic weight should have so small an atomic number ; why sodium, whose atomic weight is not much more than half that of potassium, has an atomic number nearly twice as great. The great atomic number of carbon may likewise partly arise from the smallness of its atoms. (6.) From difference in the force of attraction (Cohesion) between the atoms.—The hardest of all substances, the diamond, is pre- volume: either then its great cohesion is the consequence of the close approximation of its atoms, or this close approximation a consequence of their great cohesion ; or possibly, the strong attraction of the particles for one another, together with the close approximation thereby produced, may be the cause of the great tenacity and hardness of the diamond. The other bodies likewise follow nearly in the order of their cohesion, and the soft metal potassium terminates the series. (c.) From the dif- ferent affinities of the atoms for heat.—The stronger this affinity, the widely therefore will the atoms be kept asunder. A greater attraction for heat implies also a greater inclination to assume the gaseous state. Accordingly, the less volatile bodies, those namely which have the smallest attraction for heat, such as carbon and the more refractory metals, exhibit larger atomic numbers than sulphur, selenium, phospho- rus, iodine, bromine, chlorine, and the volatile metals. The only excep- tions to this rule are zinc and the very refractory metals, uranium, gold silver, and osmium. In a similar manner, as will afterwards be show (vid. Heat), the specific heat of bodies is greater, ceteris paribus, in pro-](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b33289190_0001_0080.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)