405 results filtered with: Green

- Digital Images

- Online

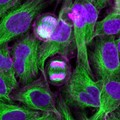

Dividing HeLa cells, LM

Kevin Mackenzie, University of Aberdeen

- Digital Images

- Online

Bacterial microbiome mapping, bioartistic experiment

François-Joseph Lapointe, Université de Montréal

- Digital Images

- Online

Woodlouse, SEM

Anne Weston, Francis Crick Institute

- Digital Images

- Online

Woodlouse, SEM

Anne Weston, Francis Crick Institute

- Digital Images

- Online

Venous invasion of colorectal cancer, modified histology

Richard Kirsch and Raw'n' Wild

- Digital Images

- Online

Madagascan sunset moth (Chrysiridia rhipheus) scales

Macroscopic Solutions

- Digital Images

- Online

Human heart (aortic valve) tissue displaying calcification

Sergio Bertazzo, Department of Materials, Imperial College London

- Digital Images

- Online

Head louse, SEM

Kevin Mackenzie, University of Aberdeen

- Digital Images

- Online

Mouse adipose tissue

Daniela Malide, NIH, Bethesda, USA

- Digital Images

- Online

Ginkgo berry

Macroscopic Solutions

- Digital Images

- Online

Healthy adult human brain viewed from the side, tractography

Henrietta Howells, NatBrainLab

- Digital Images

- Online

Euglena in green

Odra Noel

- Digital Images

- Online

Origin of life

Odra Noel

- Digital Images

- Online

Healthy adult human brain viewed from the side, tractography

Henrietta Howells, NatBrainLab

- Digital Images

- Online

HIV enzymes: reverse transcriptase, integrase, and protease

RCSB Protein Data Bank

- Digital Images

- Online

Bacterial microbiome mapping, bioartistic experiment

François-Joseph Lapointe, Université de Montréal

- Digital Images

- Online

Banded iron formations (BIFs) contain well developed iron-rich thin alternating layers or laminations as seen here. This formation occurs due to the lack of burrowing species in the Precambrian period in which this sedimentary rock was created. The name comes from the various coloured layers.

Odra Noel

- Digital Images

- Online

Raynaud's Phenomenon

Thermal Vision Research

- Digital Images

- Online

Human heart (aorta) tissue displaying calcification

Sergio Bertazzo, Department of Materials, Imperial College London

- Digital Images

- Online

Clonal tracking, mouse fibroblasts

Daniela Malide, Jean-Yves Metais, Cynthia E Dunbar, NIH, Bethesda, USA

- Digital Images

- Online

Habenular nucleus of zebrafish

Ana Faro, Tom Hawkins and Dr Steve Wilson

- Digital Images

- Online

Human heart (aortic valve) tissue displaying calcification

Sergio Bertazzo, Department of Materials, Imperial College London

- Digital Images

- Online

Raynaud's Phenomenon

Thermal Vision Research

- Digital Images

- Online

Albizia julibrissin Durazz. Fabaceae. Persian silk tree. Called 'shabkhosb' in Persian, meaning 'sleeping tree' as the pinnate leaves close up at night. Tropical tree. Named for Filippo degli Albizzi, an Italian naturalist, who brought seeds from Constantinople to Florence in 1749, and introduced it to European horticulture. The specific epithet comes from the Persian 'gul-i abrisham' which means 'silk flower'. Distribution: South Africa to Ethiopia, Senegal, Madagascar, Asia. Bark is poisonous and emetic and antihelminthic. Various preparations are widely used for numerous conditions and the oxitocic albitocin is abortifacient. However, studies on the seeds and bark of other Albizia species in Africa, demonstrate it is highly toxic, half a kilogram of seeds given to a quarter ton bull, killed it in two hours (Neuwinger, 1996). A useful tree for controlling soil erosion, producing shade in coffee plantations, and as a decorative shade tree in gardens. Photographed in the Medicinal Garden of the Royal College of Physicians, London.

Dr Henry Oakeley

- Digital Images

- Online

Paris quadrifolia L. Trilliaceae Herb Paris Distribution: Europe and temperate Asia. This dramatic plant was known as Herb Paris or one-berry. Because of the shape of the four leaves, resembling a Burgundian cross or a true love-knot, it was also known as Herb True Love. Prosaically, the name ‘Paris’ stems from the Latin ‘pars’ meaning ‘parts’ referring to the four equal leaves, and not to the French capital or the lover of Helen of Troy. Sixteenth century herbalists such as Fuchs, who calls it Aconitum pardalianches which means leopard’s bane, and Lobel who calls it Solanum tetraphyllum, attributed the poisonous properties of Aconitum to it. The latter, called monkshood and wolfsbane, are well known as poisonous garden plants. Gerard (1633), however, reports that Lobel fed it to animals and it did them no harm, and caused the recovery of a dog poisoned deliberately with arsenic and mercury, while another dog, which did not receive Herb Paris, died. It was recommended thereafter as an antidote to poisons. Coles (1657) wrote 'Herb Paris is exceedingly cold, wherupon it is proved to represse the rage and force of any Poyson, Humour , or Inflammation.' Because of its 'cold' property it was good for swellings of 'the Privy parts' (where presumably hot passions were thought to lie), to heal ulcers, cure poisoning, plague, procure sleep (the berries) and cure colic. Through the concept of the Doctrine of Signatures, the black berry represented an eye, so oil distilled from it was known as Anima oculorum, the soul of the eye, and 'effectual for all the disease of the eye'. Linnaeus (1782) listed it as treating 'Convulsions, Mania, Bubones, Pleurisy, Opththalmia', but modern authors report the berry to be toxic. That one poison acted as an antidote to another was a common, if incorrect, belief in the days of herbal medicine. Photographed in the Medicinal Garden of the Royal College of Physicians, London.

Dr Henry Oakeley