Cancer is seen as a modern disease, but there are references to cancer going back centuries, from ancient and medieval texts to 19th-century surgical manuals. Through a selection of historical images, Agnes Arnold-Forster explores changing attitudes and treatments towards the disease.

A visual history of cancer

Words by Agnes Arnold-Forster

- In pictures

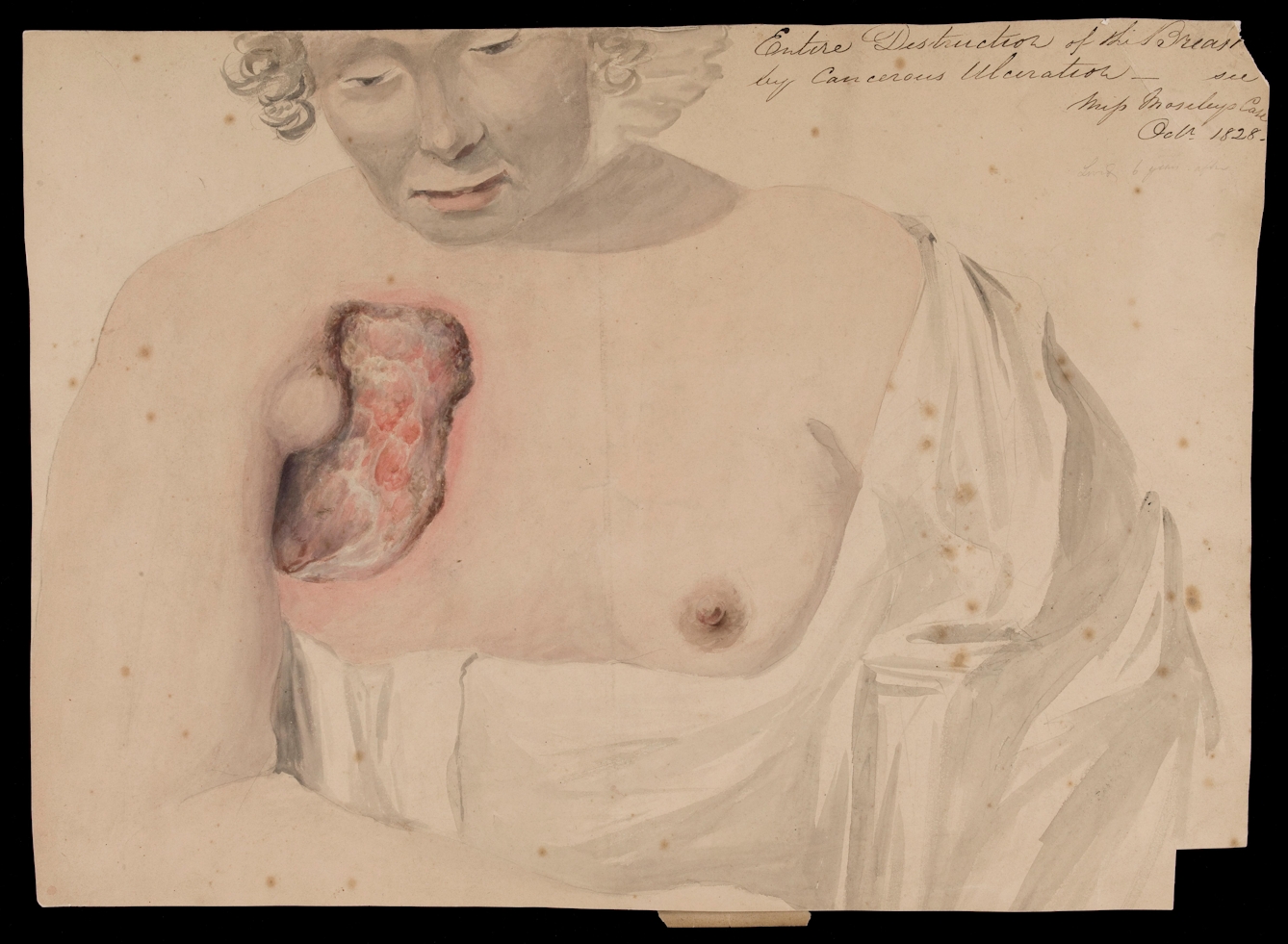

Cancer has a reputation as a modern disease – a product of industrialised society, fast food, mobile phones and carcinogenic environments. And yet the disease has been part of our lives for centuries, even millennia. There are references to cancer in all sorts of ancient, medieval and early modern texts – everything from bills of mortality to religious treatises. Moreover, early modern people – like the woman depicted here – held an understanding of cancer that was remarkably like ours today. Patients also endured invasive treatments, ranging from toxic ‘chemotherapies’ to radical surgeries. Elizabeth Hopkins had her cancerous breast removed in 1689. She seemed to have survived the operation.

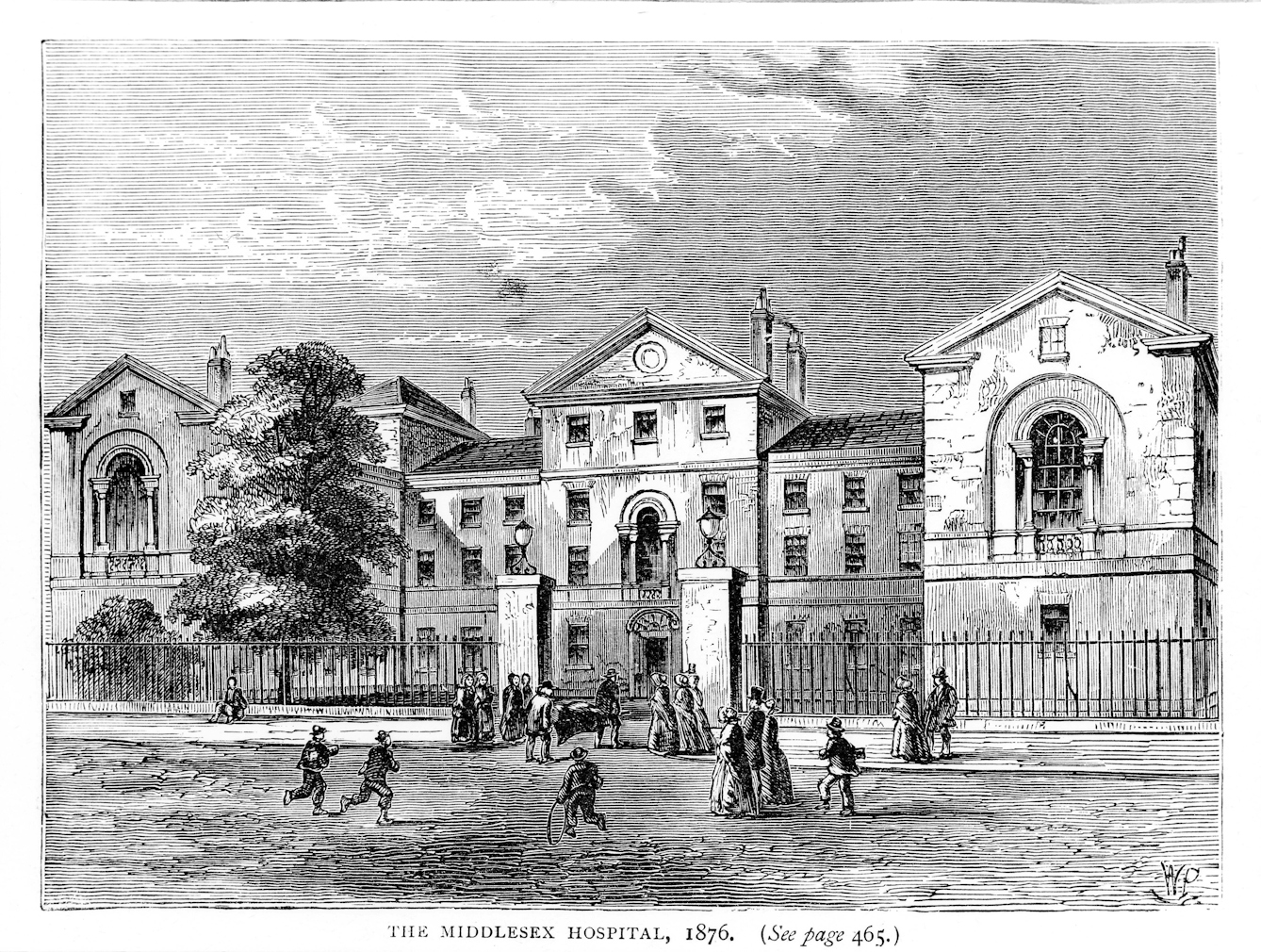

In 1792 the Middlesex Hospital (pictured here in 1876) established Britain’s first cancer wards. It was one of the world’s earliest clinical institutions dedicated to the care and treatment of cancer patients, and there were two wards, one for women and one for men. While most hospitals in this period refused to admit patients with chronic and incurable diseases like cancer, the Middlesex insisted that patients could stay until “relieved by art or released by death”. The hospital not only provided treatment for people living with cancer, but allowed surgeons and physicians to study the disease, its causes, characteristics and potential cures.

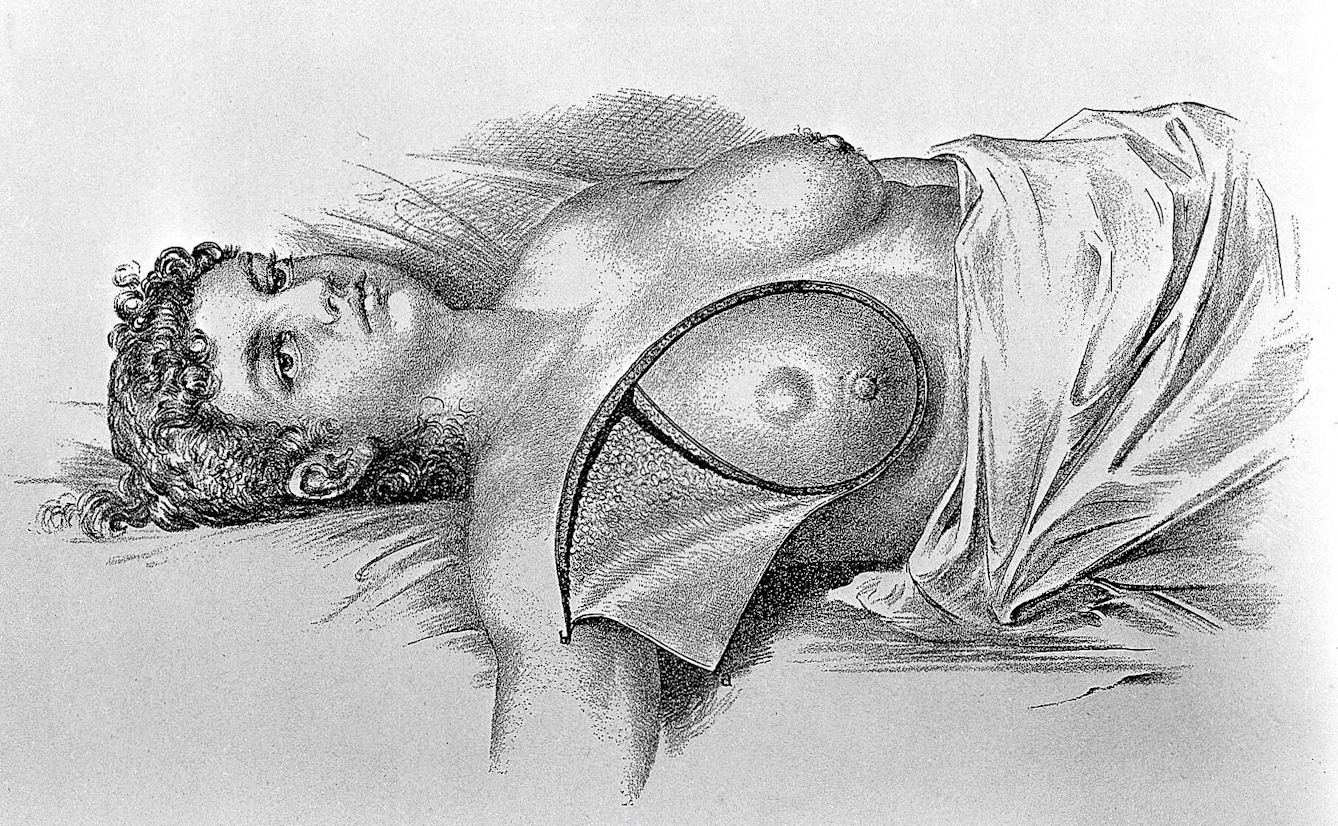

One of the greatest challenges faced by medical historians is the problem of how to access the feelings of patients in the past, especially women and members of other marginalised communities, who were less likely to record their experiences in writing. One of the biggest differences between cancer now and cancer in the early 19th century is that today, at least in Britain, most people diagnosed with the disease will have their visible tumours removed early, before they ulcerate or decay. This 1828 drawing of Miss Mosley gestures towards the pain and suffering experienced by cancer patients before the early-detection measures of the 20th century.

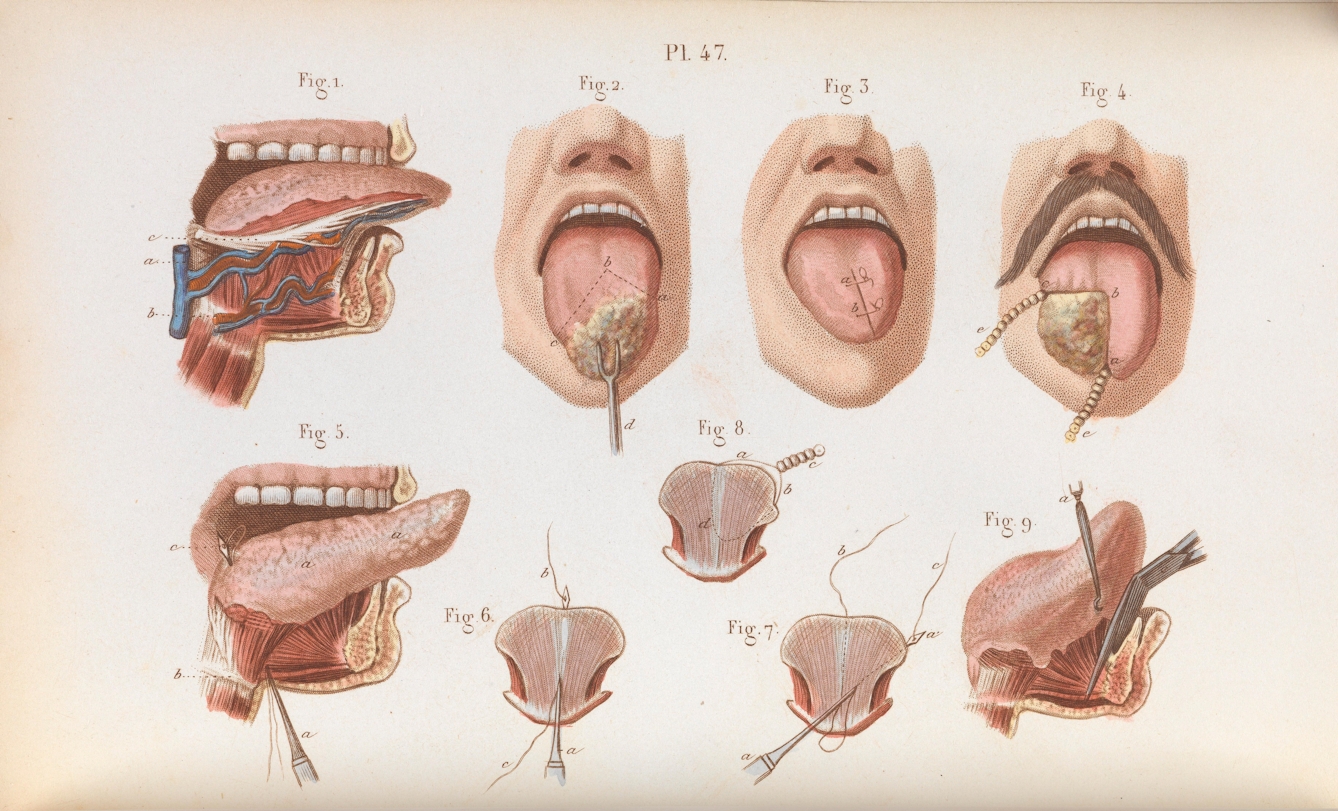

In the 19th century, surgery became the main method used by orthodox doctors to treat malignant tumours. Operations became safer and less painful with the introduction of infection control and anaesthesia. And, as surgeons became increasingly important members of the medical community, practitioners became bolder and more likely to intervene. However, surgery remained primarily palliative. Nineteenth-century doctors were well aware that the disease could spread through the body and that removing a tumour was unlikely to provide a complete cure. Instead, surgeons removed tumours to alleviate suffering and improve quality of life.

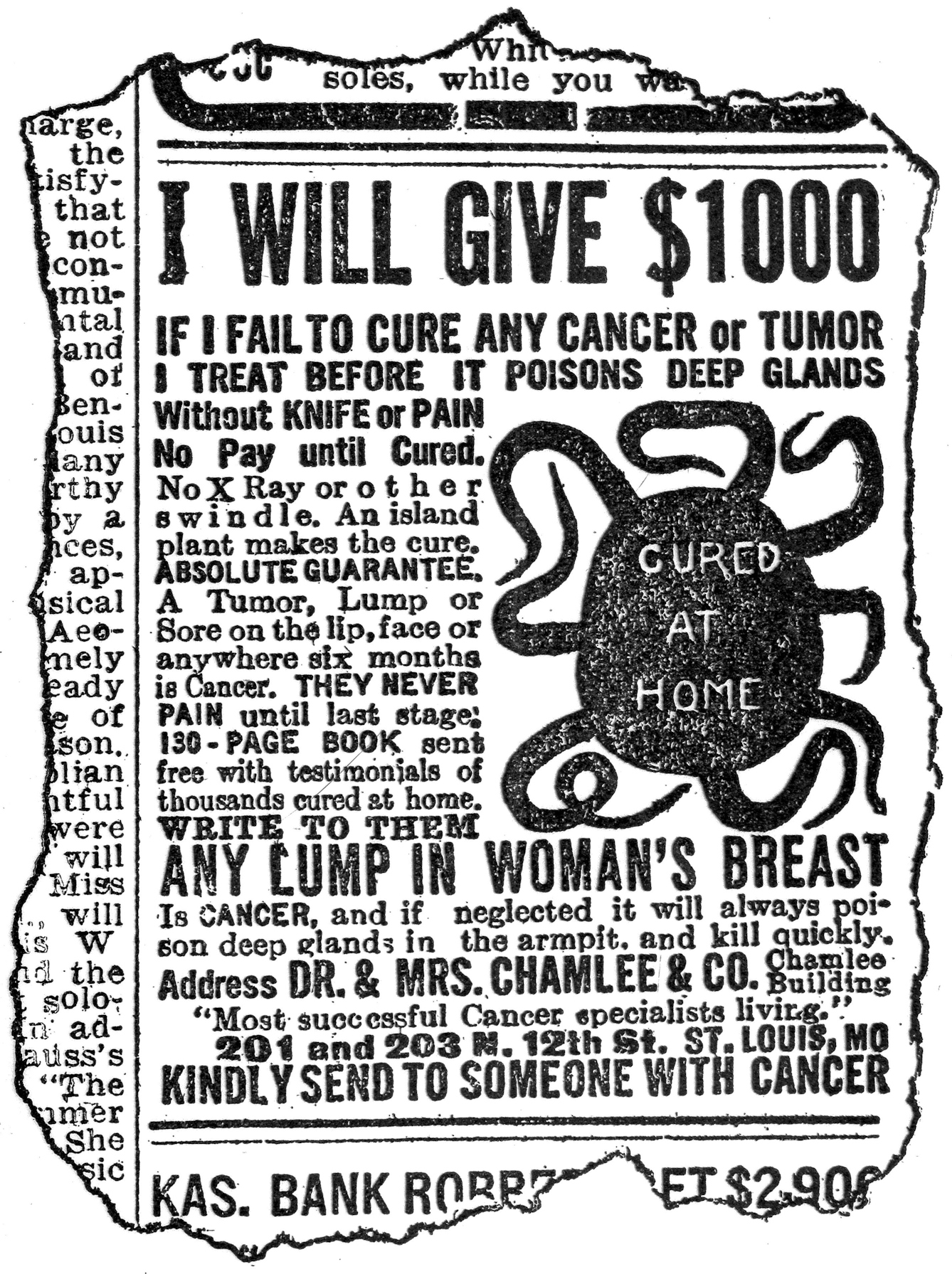

Before the advent of effective chemotherapies, orthodox surgeons and physicians could often only offer cancer sufferers palliative care. As a result, patients frequently sought advice elsewhere. Alternative practitioners – sometimes termed ‘quacks’ – have long since capitalised on this “gap in the market”. These men, and sometimes women, advertised their outlandish treatments and made grandiose claims about their efficacy. It is easy to be dismissive, but it is worth remembering that cancer sufferers were often driven by pain and desperation. Quacks also frequently promised to treat cancer without “knife or pain”, suggesting that the agony of operations also deterred people from orthodox surgery.

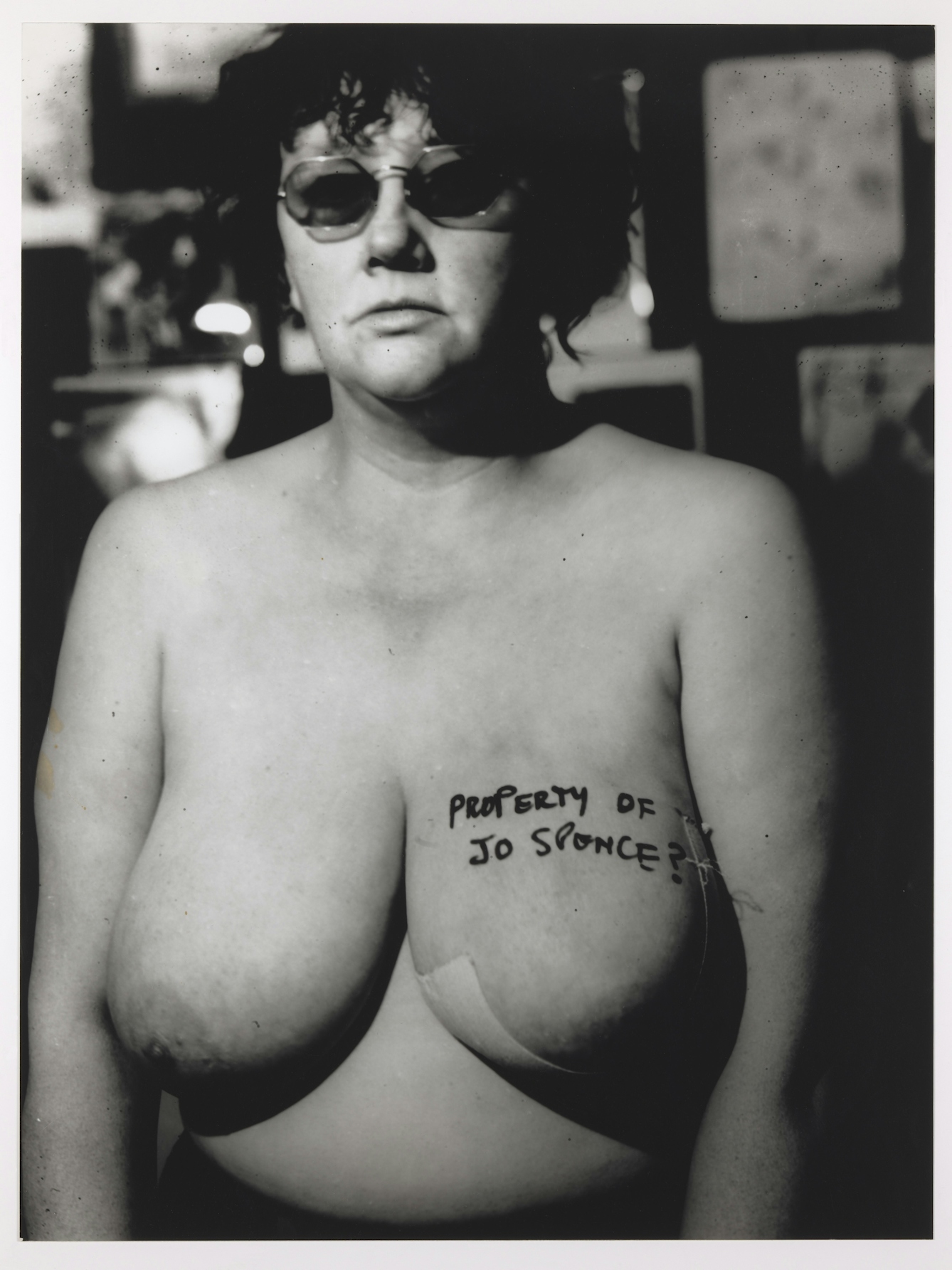

While all genders get cancer – a fact known for centuries – the disease has long been framed as a peculiarly female issue. Cancers that affected the breasts and genitals were easier to diagnose in the days before MRI scans and blood tests, so women were more frequently treated and recorded in hospital case notes and other written sources. In the late 19th century, American surgeon William Halsted developed the radical mastectomy, an extensive, and for some people traumatic, operation that was still used to treat breast cancer in the 1970s.

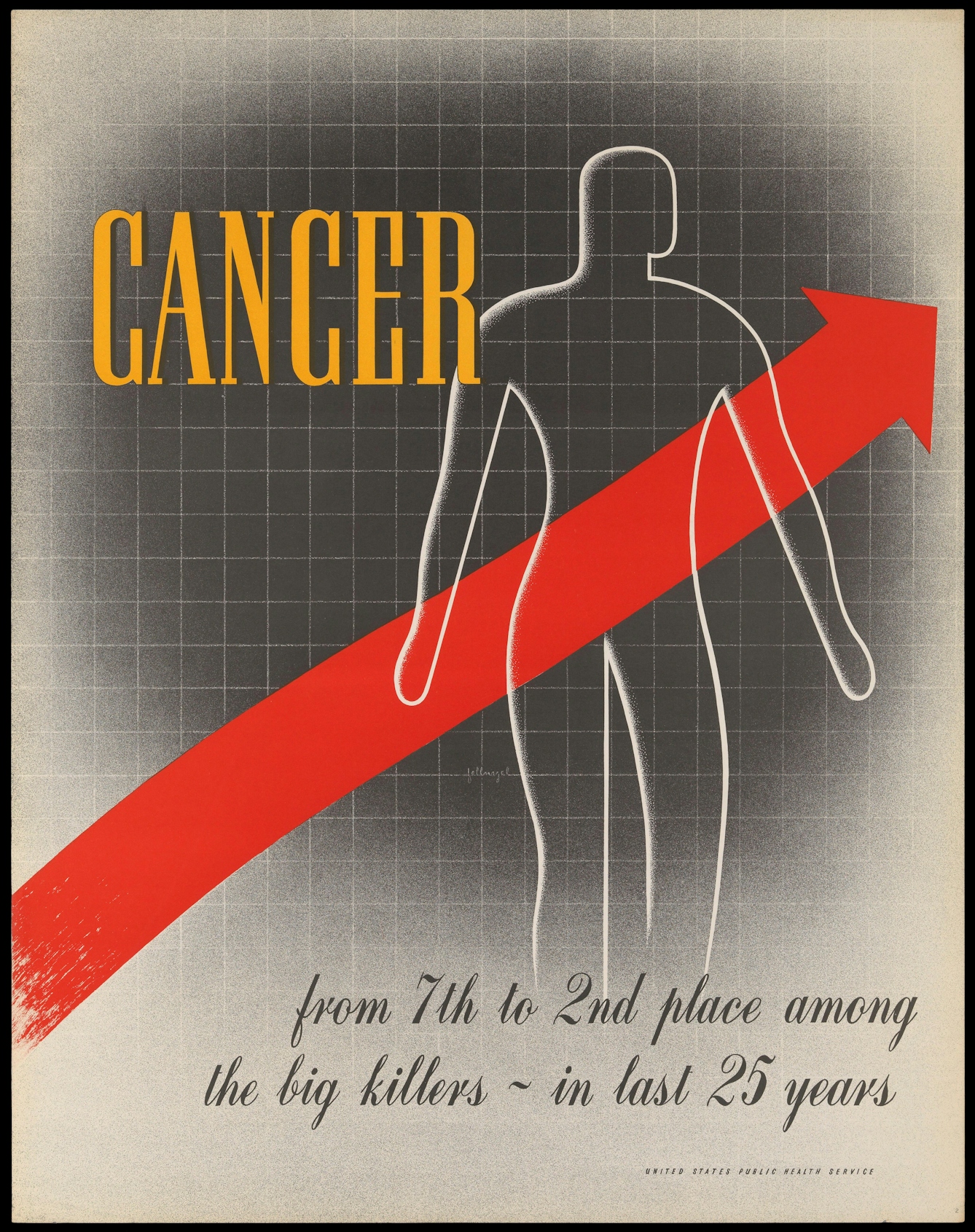

In the late 19th century, doctors, statisticians and public health professionals became increasingly anxious about the seemingly expanding “cancer epidemic” in high-income countries. As infectious diseases were brought under control, cancer steadily climbed the ranks to become one of the “big killers”. Some people suggested that this apparent increase was down to modern lifestyles and that there was something carcinogenic about 20th-century living. Others argued that the increase in cancer incidence was, paradoxically, a positive indicator of public health success. Fewer people were dying in infancy and more were surviving to adulthood, and since cancer is predominantly a disease of old age, this, strangely, was an indicator of societal progress.

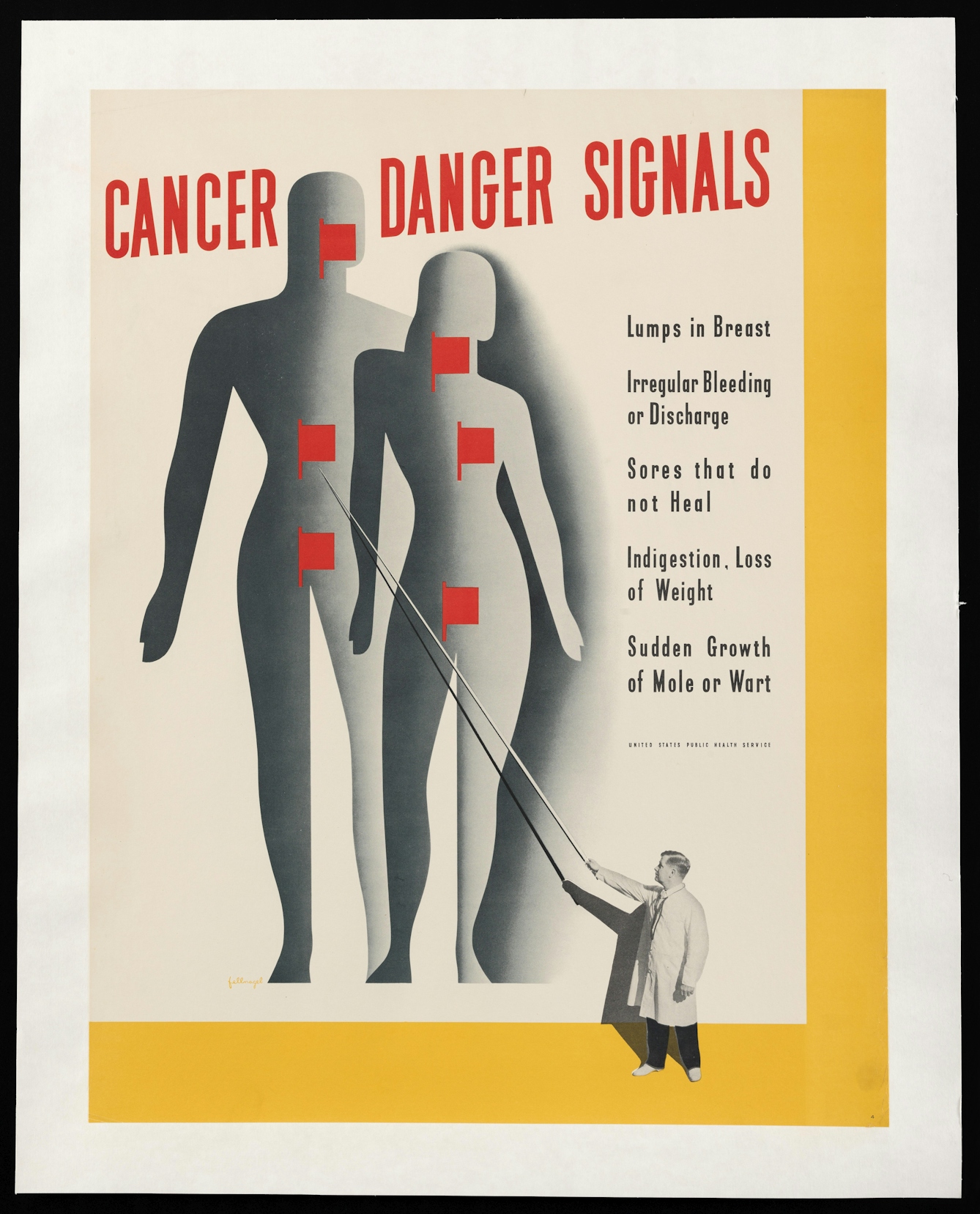

The first effective chemotherapies were developed in the 1940s. However, public health professionals and doctors both continued to think that prevention and early detection offered patients greater opportunities for survival than treatment. In the middle of the 20th century, governments in Europe and North America developed comprehensive public health campaigns designed to educate people about the early warning signs of cancers. The campaigns prompted the public to seek medical advice early and often and make ‘healthy’ decisions about what they ate, how much they exercised, and whether they smoked.

A key criticism of 20th-century cancer charities and public health campaigns is the ‘pinkification’ of breast cancer. In the 1970s, feminists fought hard to raise awareness of the disease, critique environmental and occupational pollutants, and challenge pharmaceutical companies and healthcare institutions to do better for patients. Since then, breast cancer has become increasingly commodified. The pink ribbon, originally intended as a symbol of solidarity, became a branding device used by big corporations to sell products. Feminist activists, like Jo Spence in the 1980s, have pushed back against this commodification, rejecting the reduction of their experiences and bodies to slogans and capitalist endeavours.

Cancer has been constructed as a disease of modern life, and its increase attributed to ‘progress’ and ‘civilisation’. Consequently, many late 19th- and early 20th-century doctors believed that cancer predominantly affected white Europeans and that people of colour were mostly immune from malignant disease. While this has, of course, been proven untrue, it nonetheless has had a lasting influence on the worldwide distribution of cancer resources. Although most women who now die from breast and cervical cancer (for example) live in low- and middle-income settings, global health has neglected the disease, meaning that many people living with cancer in these places go without adequate treatment. Medical funding tends to prioritise infectious disease control rather than chronic conditions like cancer.

About the author

Agnes Arnold-Forster

Dr Agnes Arnold-Forster is a writer and historian of healthcare, medicine, and the emotions. She is the author of two books, ‘The Cancer Problem’ (OUP, 2021) and ‘Cold, Hard Steel: The Myth of the Modern Surgeon’ (MUP, 2023) and her third, ‘Nostalgia: A History of a Dangerous Emotion’, will be published by Picador in April 2024. She is a Chancellor’s Fellow at the University of Edinburgh, and together with Caitjan Gainty, she runs the Healthy Scepticism project.