We know it’s spring when the migrating birds return and we hear a noticeable increase in birdsong. Take a look as we train our binoculars on representations of birds in our collection: we’ll encounter classical fables, early modern receipt books and Victorian sketchbooks, all of which show our changing relationship with birds.

Bird-spotting from medieval to modern times

Words by Ross MacFarlane

- In pictures

One of the oldest ways of looking at animals is to tell moral stories about how we should behave. Aesop’s fable of the Hawk and the Nightingale has had numerous retellings: this image of it dates from the 17th century. In most, the Nightingale begs for mercy from the Hawk that has just caught it; the Hawk refuses, judging that his empty stomach overrides the Nightingale’s pleas.

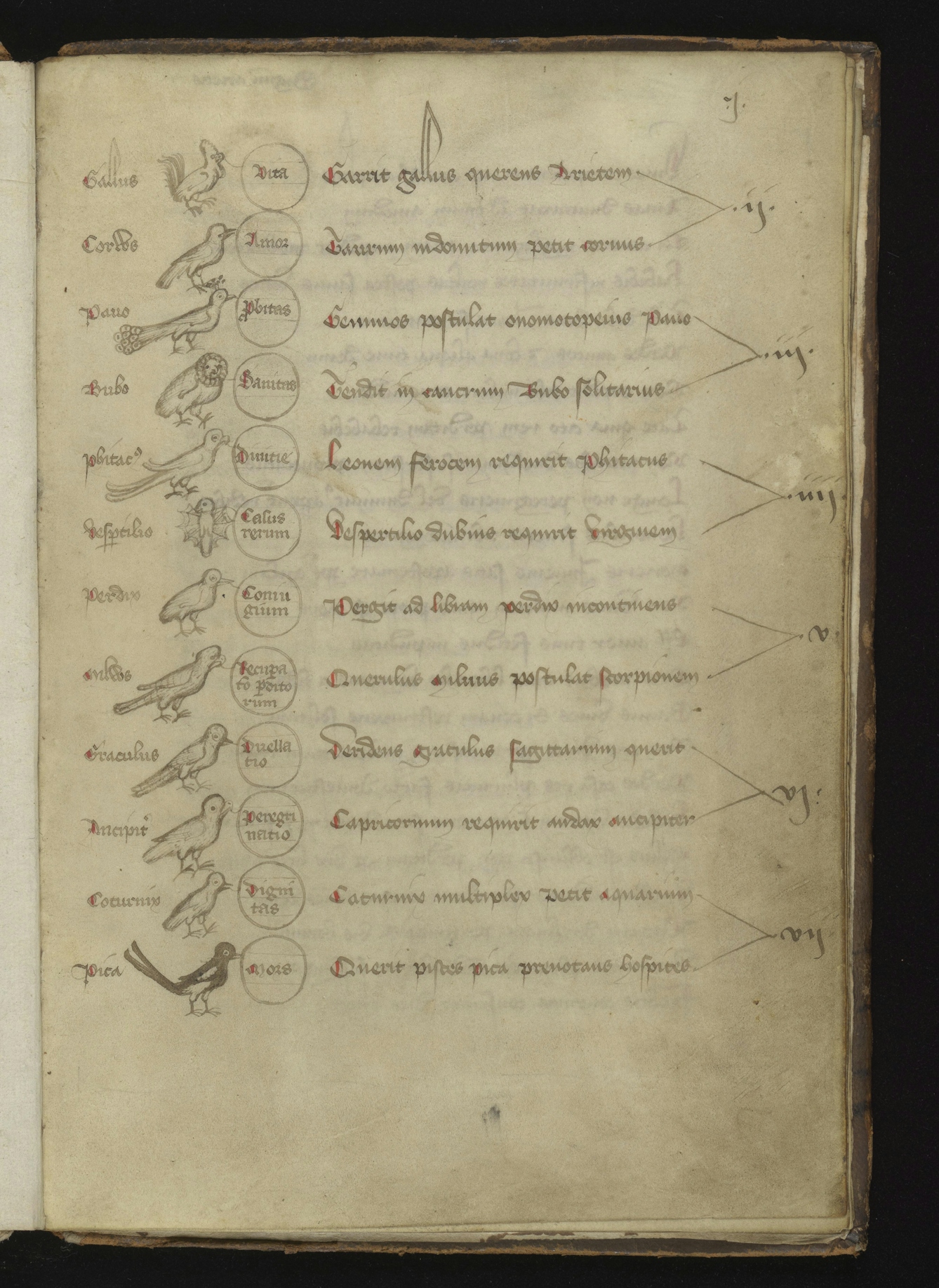

As well as using them as characters to tell how things “should be”, people have used birds in divination and fortune telling. Dating from the mid-15th century, this manuscript consists of a fortune-telling game that matches birds to zodiacal signs. The birds depicted include a chicken, a crow, a peacock – and a bat (which was still classified as a bird in medieval encyclopedias).

First published in 1491, ‘Hortus Sanitatis’ showed animals of the natural world, along with the belief that God had placed them on Earth to supply cures for humanity’s ills. ‘Hortus Sanitatis’ was one of the finest illustrated early printed books, dubbed by some as the first encyclopedia of the natural world. Many of the illustrations depict fabulous creatures – mermaids and unicorns both appear – but the more prosaic cockerel is depicted too.

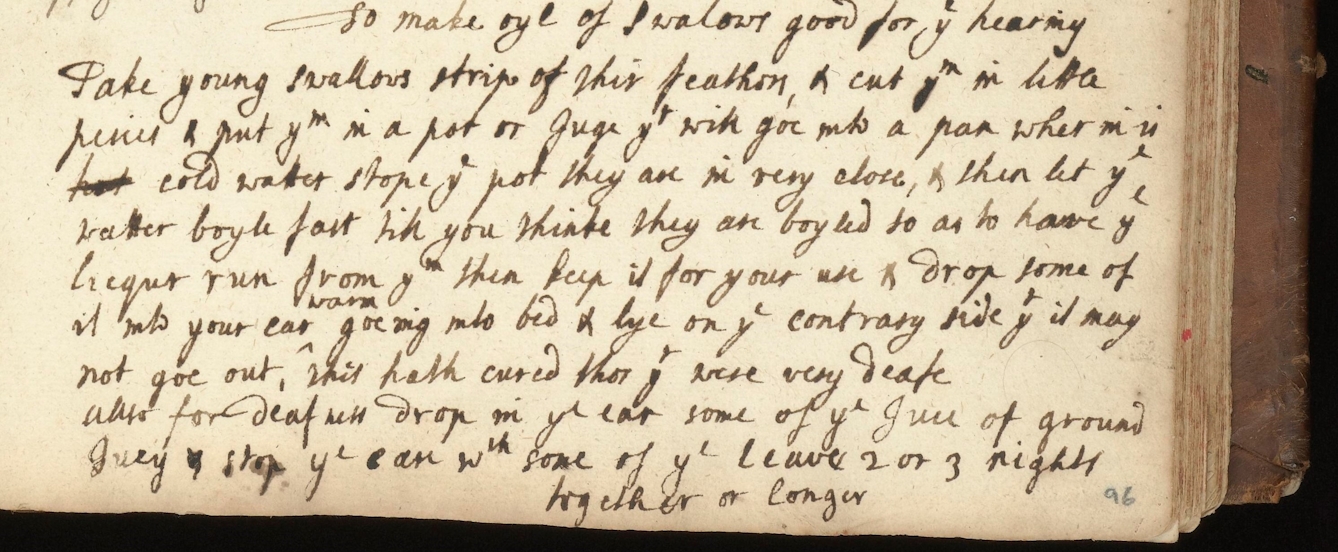

Birds make many appearances in early modern receipt books – usually as the main constituent part of a recipe (which gives us an insight into diets of the time). They sometimes make an appearance in medicinal receipts – or prescriptions – too. As a cure for deafness, this 17th-century manuscript recommends ‘oil of swallows’: one of the more remarkable remedies of the period. It's hard to believe anyone made it, because it required catching lots of birds and beating them to a pulp without them escaping. However, historians have shown there is evidence to show that attempts were made to make it (and that its efficacy was attested to by some).

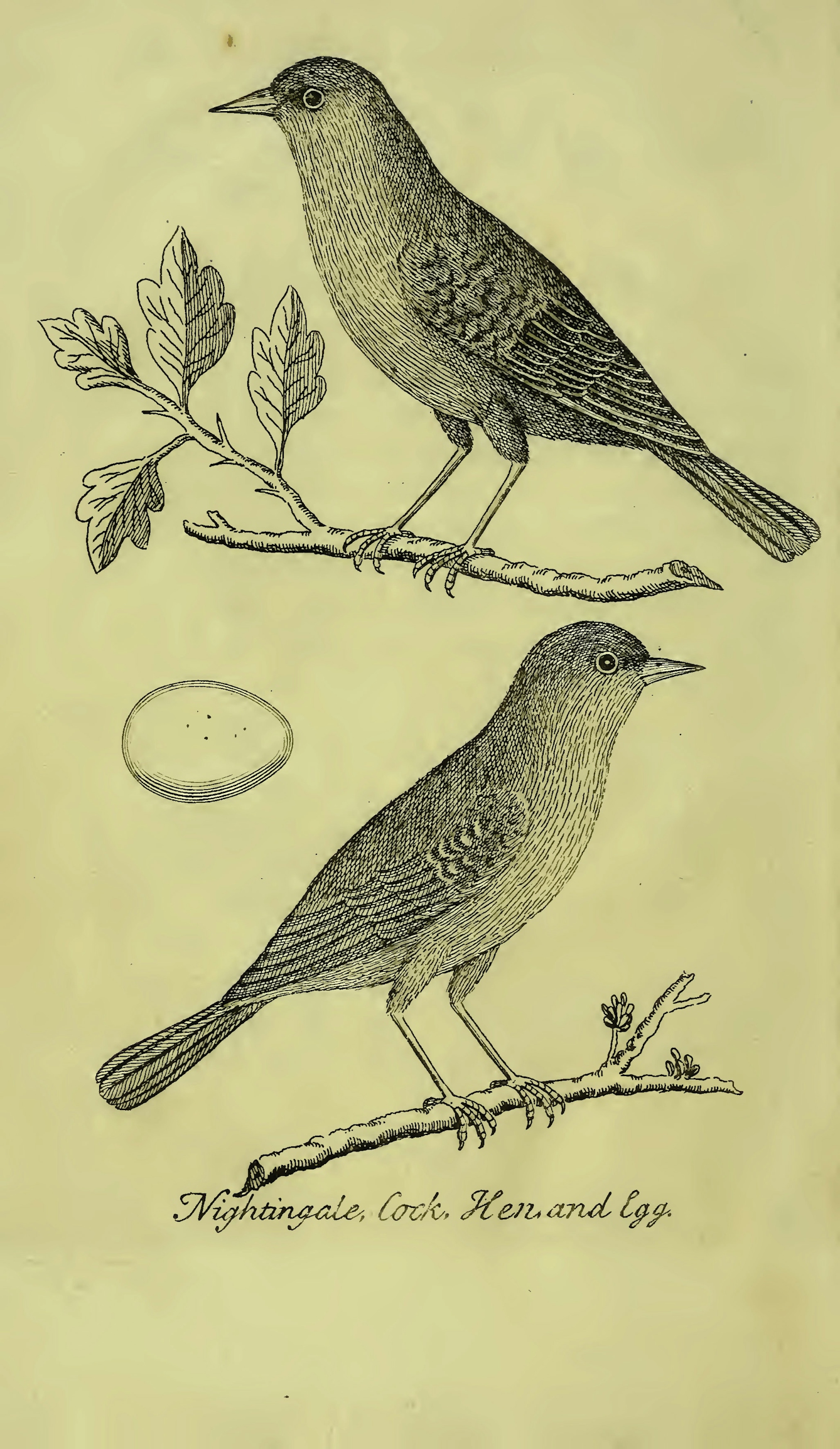

Describing birdsong is tricky. The polymath Athanasius Kircher attempted to do so through musical notation in his work ‘Musurgia Universalis’ (1650) but for Ebenezer Albin, author of ‘A Natural History of English Songbirds’ (1737) the written word had to suffice: the nightingale “…sends forth his pleasant notes with so lavish a freedom that he makes even the woods to echo with his melodious voice”. While Albin’s lush language speaks of a growing appreciation of birds, he still views them as creatures designed for our pleasure: “Singing birds… were, undoubtedly, designed by the great Author of Nature, on purpose to entertain and delight mankind.”

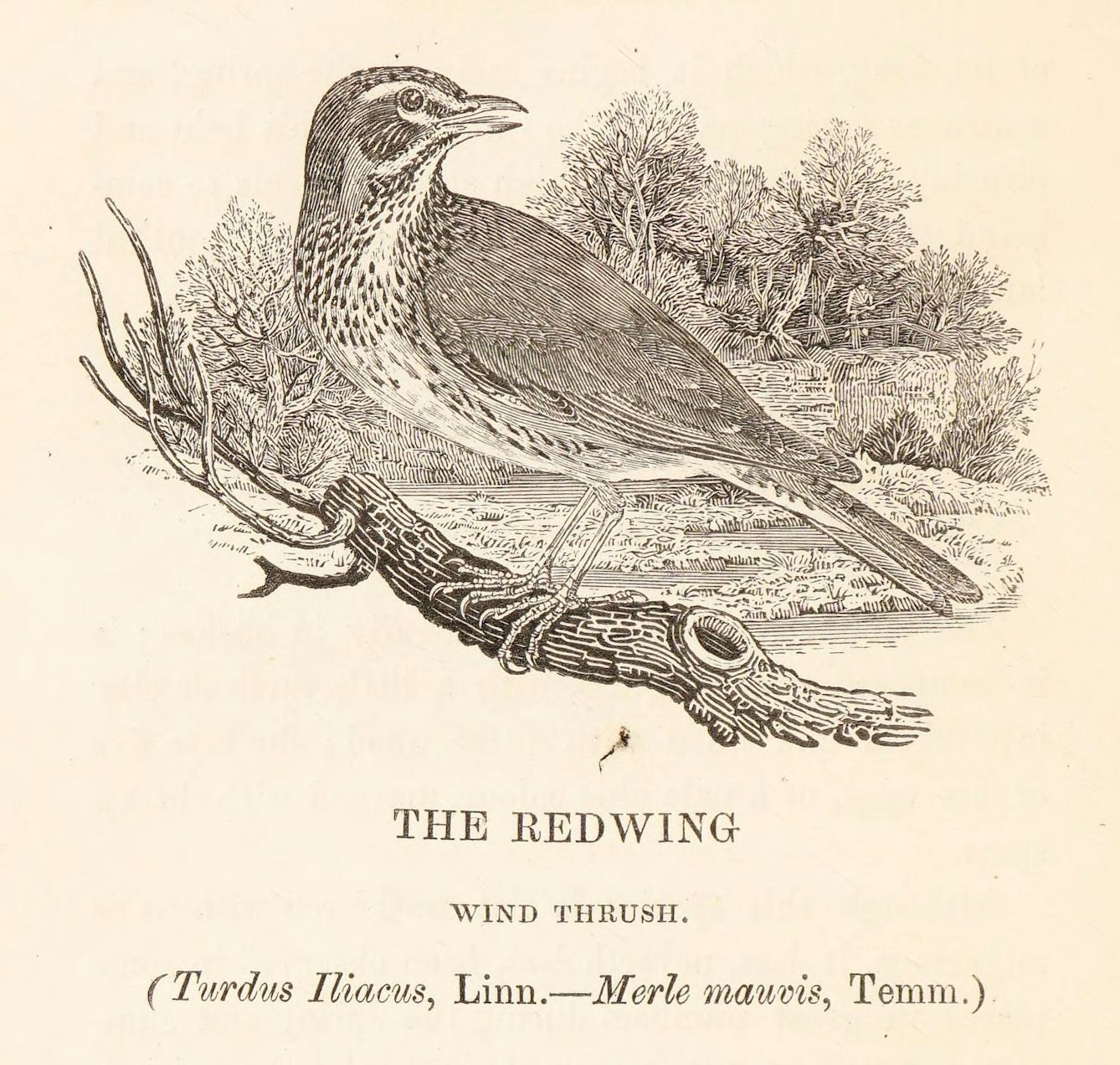

Thomas Bewick’s ‘History of British Birds’ is now hailed as key to turning the British into a nation of nature lovers. It was a bestseller on publication in the late 18th century, with Bewick’s woodcuts praised for their attention to detail and accuracy. These illustrations are not just neutral displays of rural idylls, though; often gritty reality creeps into his scenes. For instance, admire this depiction of a redwing, but look closely and you will see the tiny detail on the right of a hunter with a rifle.

John Gough (1757–1825) was a noted natural philosopher, often corresponding from his home in Kendal in the Lake District with other leading Quakers. He had also been blind since contracting smallpox as an infant, so all his records are based on his other senses. In this journal, Gough records meteorological conditions marking the coming of spring in 1809. He records both precise, measurable data (temperature, wind speed, rainfall, etc.) and sensory changes like the budding of leaves on trees and of flowers, and the song of the cuckoo (which Gough hears on 27 April).

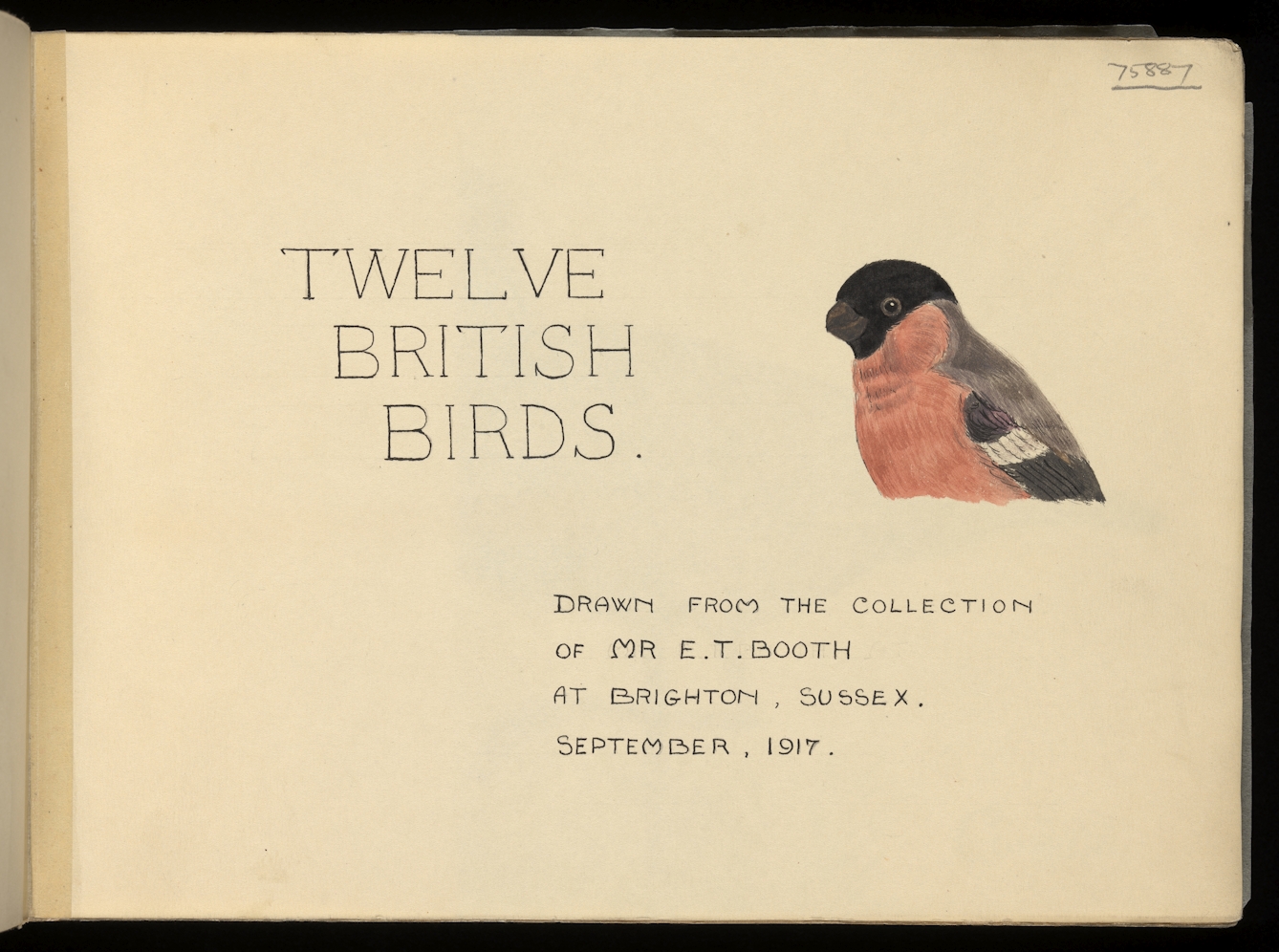

The 19th century saw the growth of taxidermy. Edward Booth (1840–90) had a huge taxidermic bird collection. His ambition was to try and capture an example of every single British bird – resident or migratory. When he died, he was about 50 birds short of his target. This notebook was compiled by an unnamed visitor to his collection in 1917, by which time Booth’s private collection had been opened to the public in Brighton.

The birds in Booth’s collection were displayed in dioramas, which attempted to recreate their natural environment. The illustrations in the sketchbook remove these settings. In this instance, the sooty tern appears to be straining at the margins of the page. Just like the taxidermic birds, the notebook captures a frozen moment in time. Many of the birds are much harder to spot now because, of the twelve ‘British Birds’ featured in the sketchbook, half of them are now on the RSPB’s ‘Birds of Conservation Concern’ list.

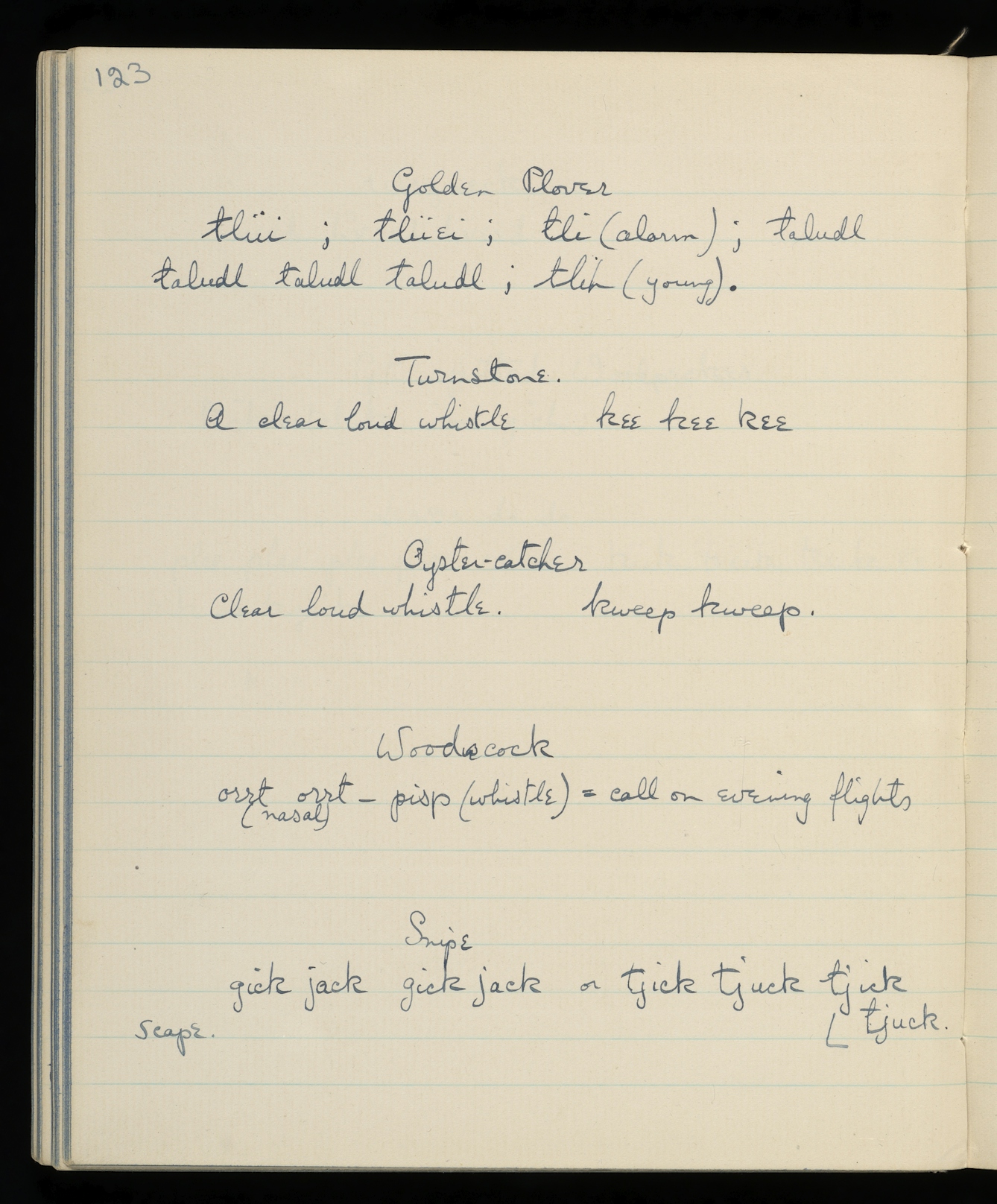

Another notebook captures a sense of ornithology at the start of the 20th century, moving away from taxidermy and back to the open air. Its young creator diligently lists sightings of birds and tries to capture their song in phonetic description, illustrating the passion for this hobby among its followers and the levels of detail that birdwatchers were starting to introduce to their practice.

These notes were made by the young Sir Christopher Andrewes (1896–1988). His interest in birds and in making detailed observations may well have contributed to his career as a leading British virologist, who discovered the influenza A virus (which causes influenza in humans, birds and some mammals). Birdwatching is a hobby we might be enjoying at the moment to distract us from thoughts of illness, but Andrewes’ notebook shows how the hobby can lead to knowledge that can actively help us to battle ill health.

About the author

Ross MacFarlane

Ross MacFarlane is a research development specialist at Wellcome Collection. He has researched, written and lectured on the collections and other topics at the intersection of death, folklore and medicine.