For thousands of years, and in many different cultures, people have practised bloodletting for health and medical reasons. Julia Nurse explains where and when bleeding was used, how it was done, and why.

Bleeding healthy

Words by Julia Nurseaverage reading time 5 minutes

- Article

Bleeding was thought to treat a myriad of conditions, including asthma, cancer, gout, convulsions, indigestion, smallpox, consumption, insanity, jaundice, the plague and even heavy menstruation, nosebleeds and heartbreak. It was used in lots of places around the world through history.

Historians believe that bloodletting was first practised in ancient Egypt. The ‘Book of Knowledge and Ingenious Mechanical Devices’ by Al-Jazari (1136–1206) described a device believed to have been used by the ancient Egyptians(view in catalogue) to bleed patients: it featured two scribes sitting on top to measure the patient’s blood, which flowed into a basin below.

In ancient Greece, physicians like Hippocrates and Erasistratus believed blood formed one of the four humours (blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile), which had to be balanced for good health, sometimes by letting blood.

The practice of letting blood continued in Europe in the Middle Ages, following ancient Greek theories and guides. It formed the backbone of Western medicine for centuries, despite its sometimes fatal results.

Bloodletting was also used in many other places too, including by the Chippewa in North America, the Mayans in Mesoamerica, in Uganda, from the eighth century in Tibet, in traditional Chinese medicine practices, as part of a long history of being used in Ayurvedic medicine in India, and was even performed on animals in veterinary medicine(view in catalogue).

Why did people think that letting blood would make them healthier?

Bloodletting went hand in hand with purging, starving and vomiting techniques to rid the body of nasties and maintain a healthy equilibrium. ‘Bleeding’ a patient was modelled on the process of menstruation, based on Hippocrates’ belief that it functioned to “purge women of bad humours”. Since many bodily complaints were thought to be caused by imbalances, bleeding was used a lot as a treatment.

Bloodletting was popular among patients of all social standing. People believed poor circulation was caused by stagnated blood, which needed to be removed to restore flow, and that some people had too much blood, which also needed removing.

When would people be bled?

In one so-called “leech book(view in catalogue)” (a physician’s manual) from the 15th century, instructions for good health include bloodletting alongside a healthy balanced diet and urine-colour diagnosis. According to this guide, bloodletting could be done any time of the year, though here we see a warning that it is perilous to bleed on the 21st day – this would have been for astrological reasons, which were used as guides for many health-related things at this time.

Such guidelines continued to be adhered to in the early modern period, by which time bloodletting was commonly practised in the home, usually before and after the cold months, which was thought to help avoid the accumulation of corrupt and waste matter.

Who bled people?

Monks, who were traditional practitioners of medicine, were forbidden from letting blood. This meant that bloodletting had to be done by other people.

Who were the bleeders?

Barbers in monasteries, already used to working with sharp blades, were called to assist monks by letting blood. For hundreds of years, barbers were involved in bloodletting. In 1540, the Company of Barber Surgeons was formed, and it lasted until the surgeons broke away in 1745. This Barber Surgeons’ plaque sign shows someone being bled by the disembodied hands of members.

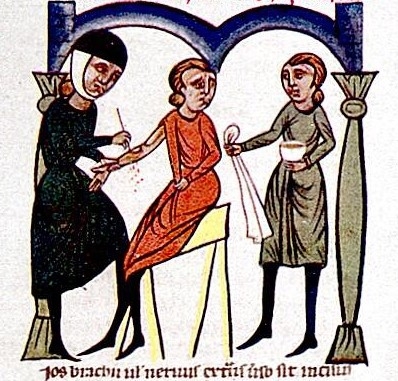

Women herbal practitioners used to bleed people too. The woman in this image is depicted as being caring and careful, but other images of women practitioners(view in catalogue) were less flattering.

Bloodletting was sometimes performed at home by inexperienced hands, a risk deemed worth taking if no surgeon was close to hand. For example, Adam Eyre recorded in 1647 that “after dinner, I blooded my wife in her sore foot, which bled very well”.

Where on the body were people bled?

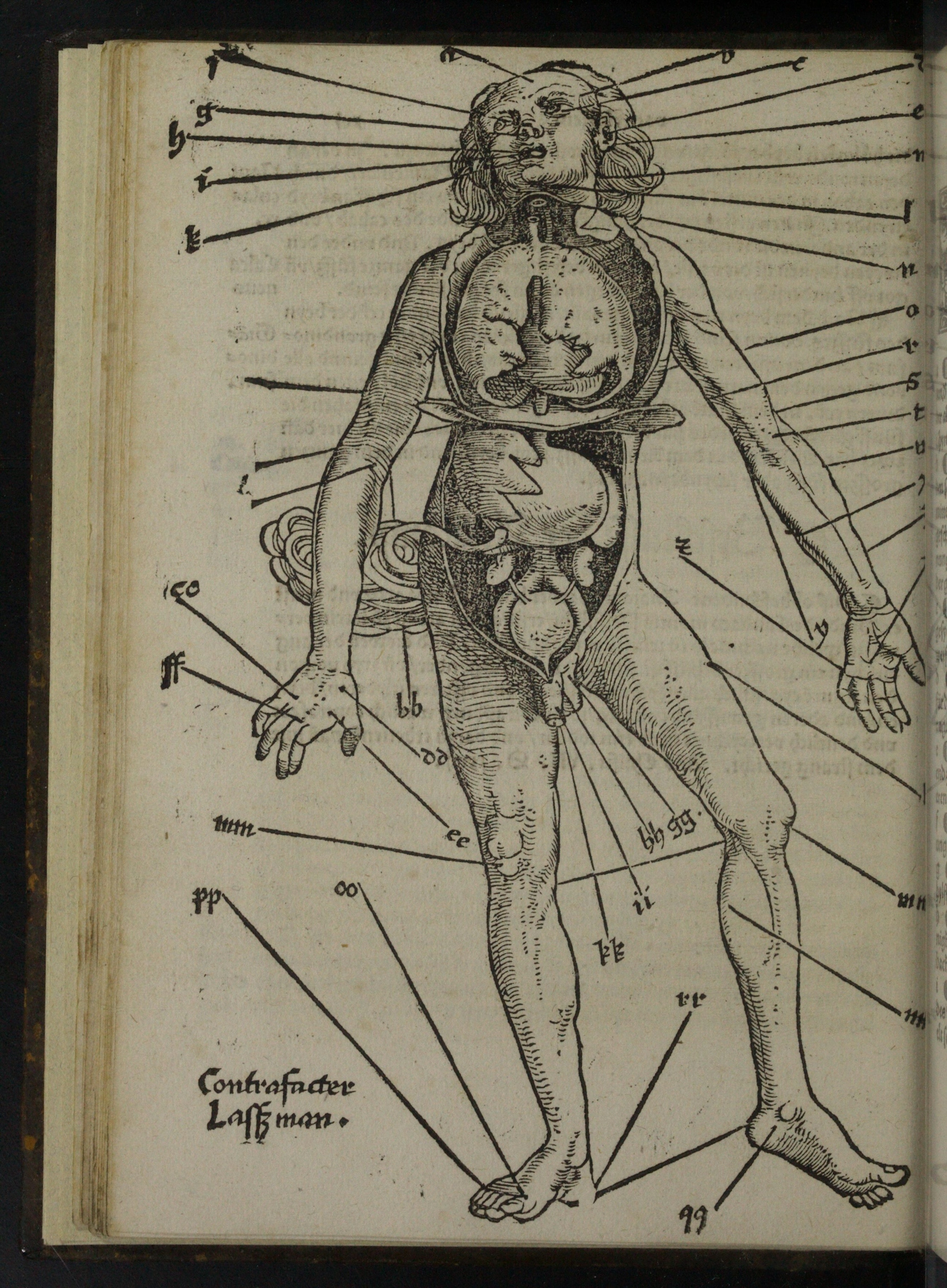

Where to bleed depended on where someone was hurt or diseased. Guides on bloodletting points in the body were printed in medieval medical manuals such as Hans von Gersdorff's Feldtbuch der Wundartzney (1517), which was aimed at military field surgeons.

Most early modern bloodletters followed the Persian polymath Ibn Sina’s 11th-century ‘Canon of Medicine’, which stated that the bloodletting was to be administered from the side of the body opposite to the disease’s location. Jacobus Sylvius believed in this opposite-side or “revulsive” bleeding. But others argued otherwise: Pierre Brissot (1478–1522) challenged centuries of tradition by making a case(view in catalogue) for “derivative” bloodletting, to be done on the same side as the illness. A fierce battle between “revulsive” bleeders and “derivative” bleeders ensued and can be seen in medical texts from the time. Gersdorff's guide offers a compromise by illustrating both.

This woodcut shows the appropriate places to draw blood. It is from Hans von Gersdorff’s ‘Feldtbuch der Wundartzney’, a portable manual for military field surgeons, first published in Strasbourg in 1517. The Bloodletting Man illustration was drawn from observations of a dissection performed in Strasbourg on the body of a hanged criminal.

Bloodletting was even performed from the head. This may have been to alleviate ailments that were associated with the head, notably seizures, which were often described as “falling sickness”, but now believed to be epilepsy.

What tools did people use for bloodletting?

Phlebotomy is used today to describe the ubiquitous blood test. The name is derived from the original ancient Greek phlebos for blood vessel and tome, meaning to cut. Various tools have been used to cut and bleed patients across cultures.

In pictures

Fleams usually comprised two or three blades. These replicated much earlier use of sharp fish teeth, stones or horns to cut the skin.

The scarificator was in use by the 17th century. Notably, a scarificator was used on Charles II as he was dying(view in catalogue). Scarifiers had multiple blades that shot out with the press of a spring-loaded lever, creating an instantaneous series of parallel cuts in the skin of the patient – this supposedly made the process quicker, though by no means less traumatic.

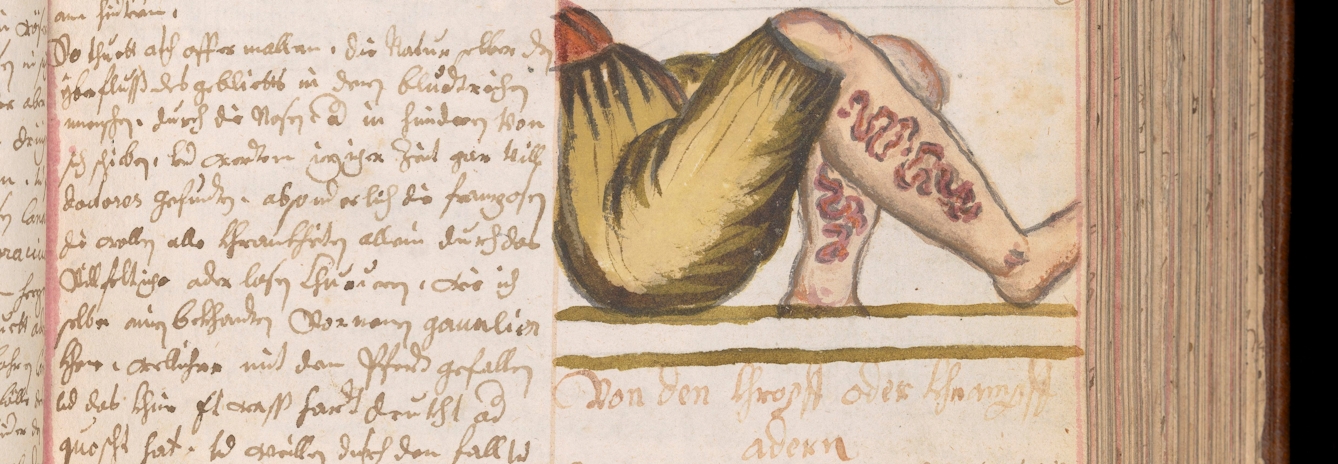

Bloodletting could also involve bloodsucking. Leeches had long been used to draw out blood when cutting methods were not possible. In the 17th-century manuscript above, numerous leeches have been applied to a man’s leg; he may have been suffering from gout or a similar painful complaint.

This method was known as “blood leeching” or “sangui-suction”, a method still receiving approval in an early 19th-century treatise on the topic(view in catalogue). In one case, 24 leeches were applied to the temple and back of the head of a patient suffering from “phrenitis” (inflammation of the brain), in addition to “copious blood-letting from the arm” and “powerful purgatives”. This punishing treatment was said to have “removed the violence of the disease” (seizures), while also depriving the body of essential fluids.

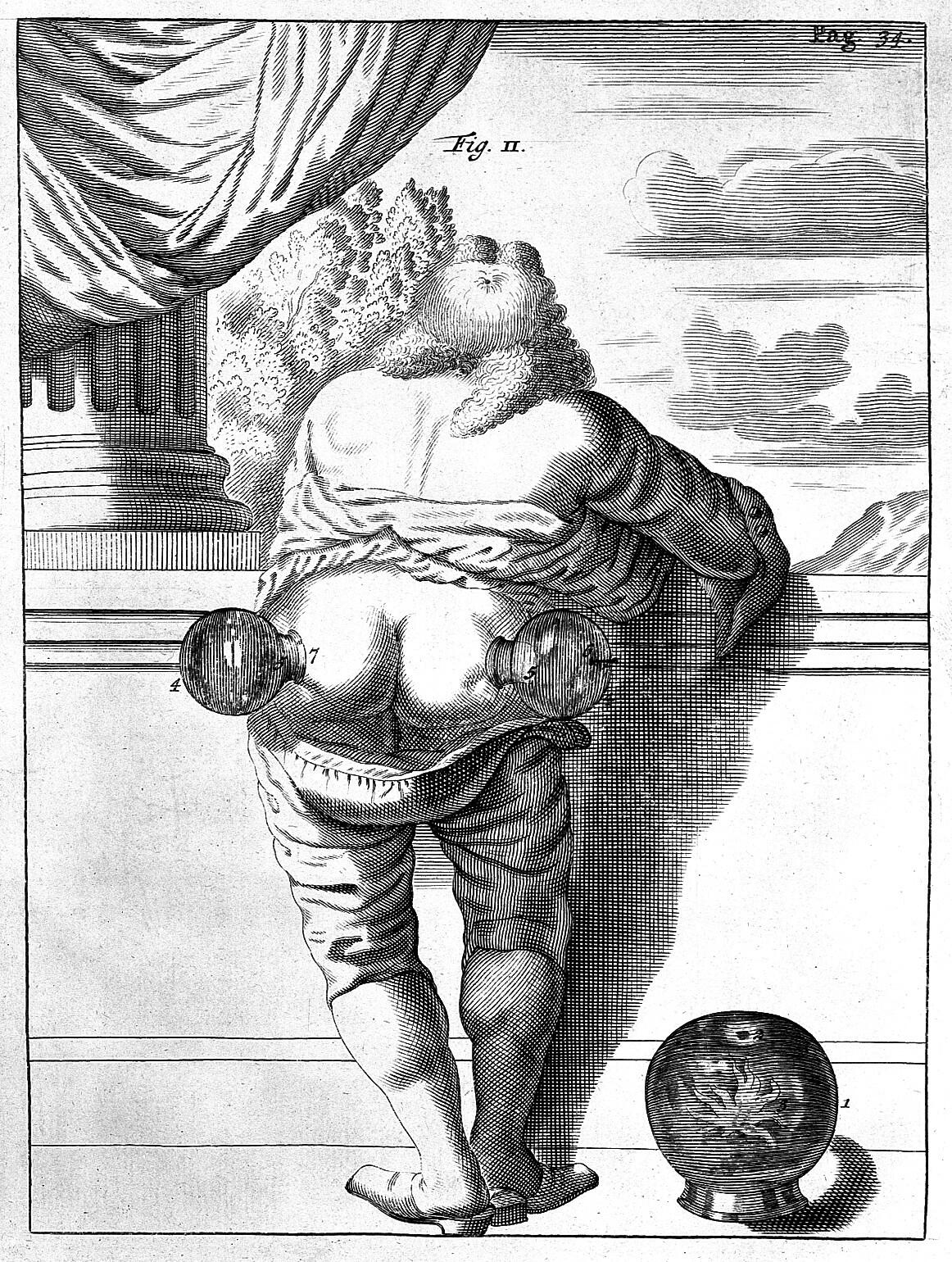

Cupping glasses were also combined with other techniques of releasing blood, largely to increase blood flow. Cupping was called ‘wet’ cupping if the skin was pierced. Cupping glasses have been applied to the buttocks of a gentleman suffering from sciatica in this image from the 17th century.

The dangers of bloodletting

Not surprisingly, sometimes there were fatal results from bloodletting. It required careful attention and the dangers of inattentive physicians were shown in illustrations.

In pictures

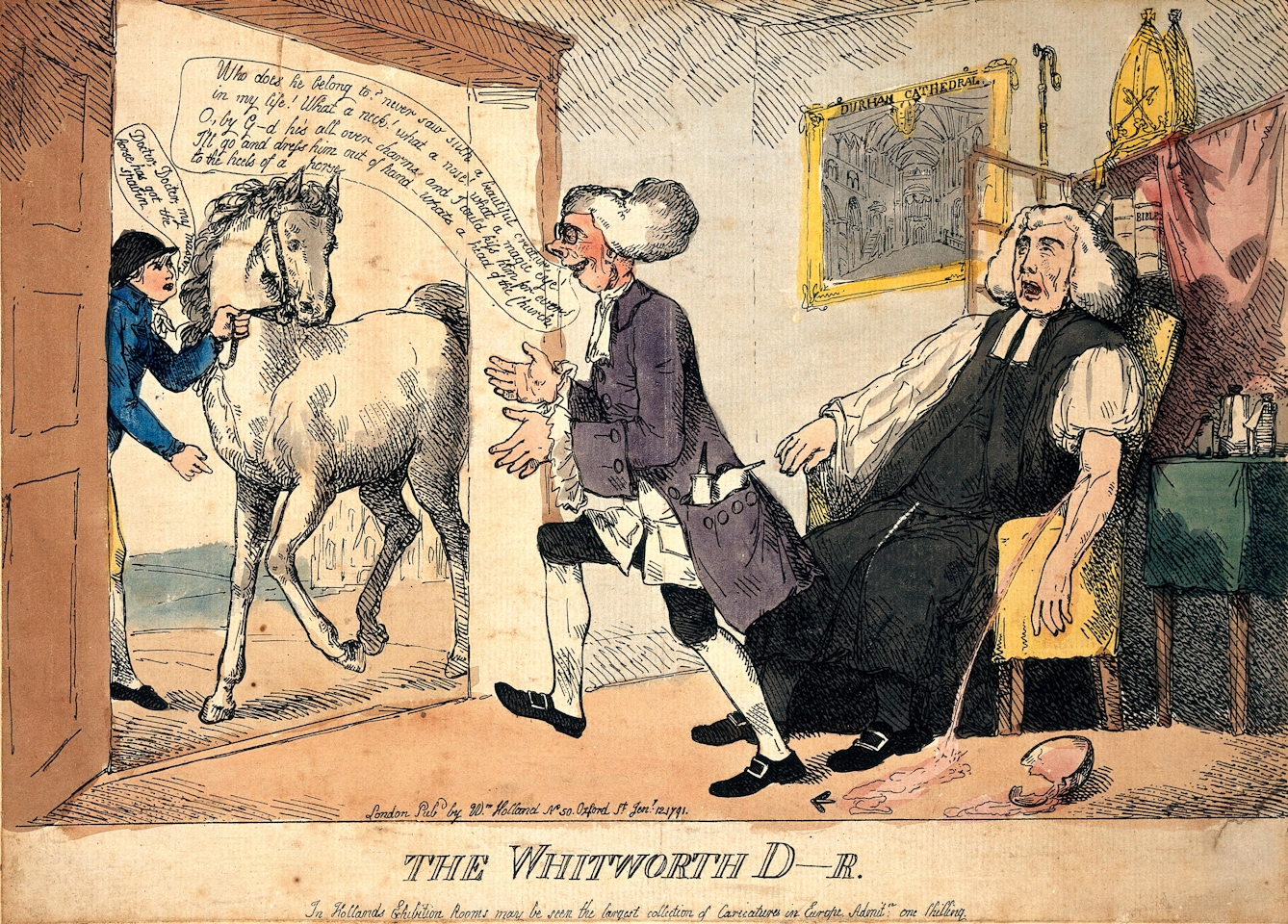

In this satirical scene from 1791, a surgeon letting blood from Thomas Thurlow, Bishop of Durham, abandons his patient to haemorrhage to attend a sick horse outside, doubtless with catastrophic results.

In this humorous print, the doctor is a careless practitioner, because he prescribes, absurdly, that a family should be bled by “Eight units for the whole family: divide yourselves up!” A more careful physician would have taken more blood from the young and fit adults, and less blood from children and the aged.

Patients may have wanted witnesses to their bloodletting for this reason, and we often see witnesses in images such as this one. On the right of this scene in an oil panel from 1665, a man with a wooden leg can be seen watching the proceedings as another person holds onto the blood cup and a woman stands behind, possibly representing a ‘wise woman’. The boy in this painting appears younger than the 14-plus age rating for an apprentice, and according to his refined dress, was likely the servant of the woman being bled, rather than an assistant to the surgeon.

The decline of bloodletting

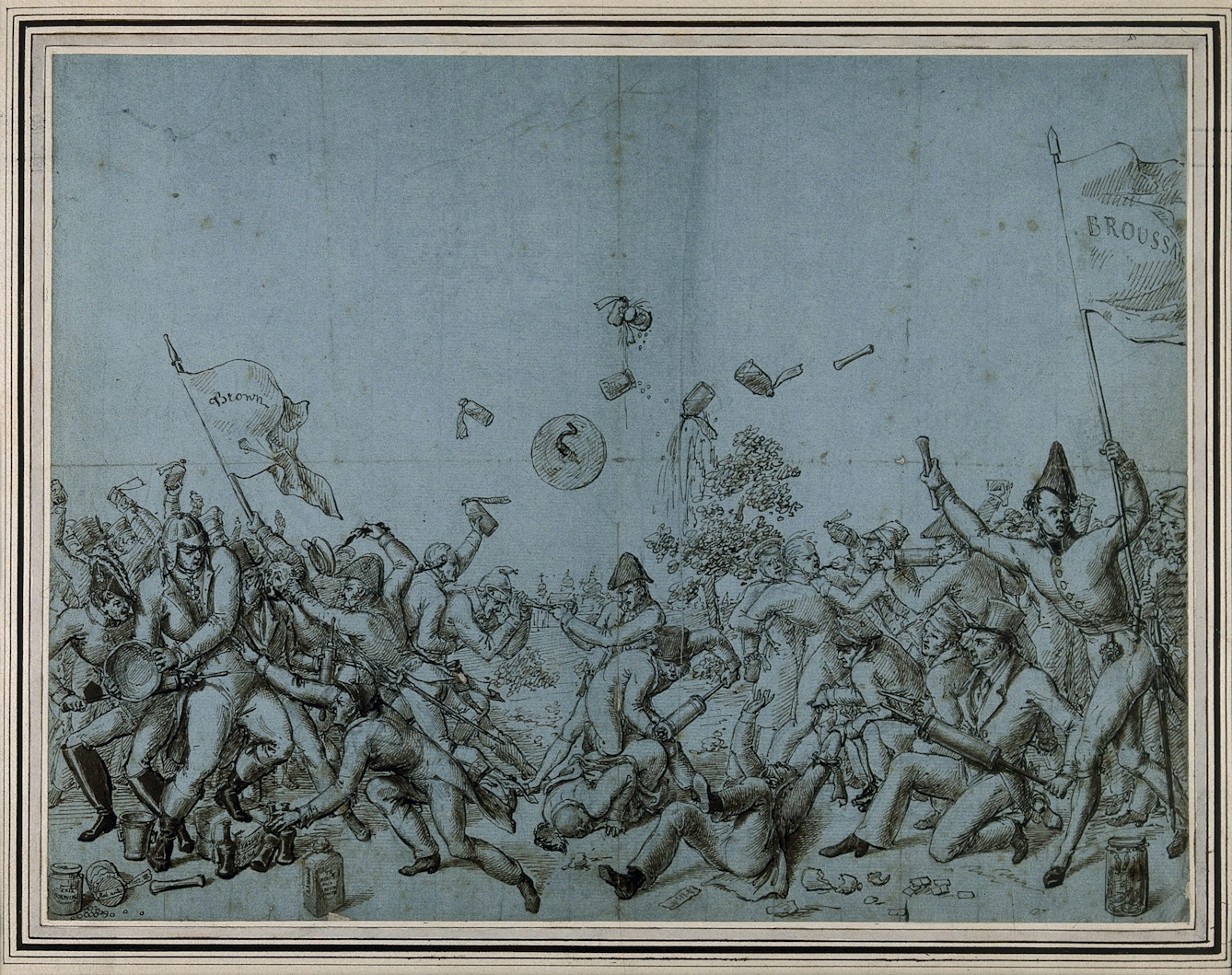

Other systems began to rival bloodletting. Brunonianism, the theory of John Brown (1735–88), regarded most illnesses as due to a deficit of stimulation, requiring treatment with medicines based on opium or alcohol. François Joseph Victor Broussais (1772–1838) believed in bloodletting and tried to ridicule Brown and his followers.

This drawing, probably by a French or German artist, shows a battle between the rivals of Brown (on the left) and Broussais (on the right).

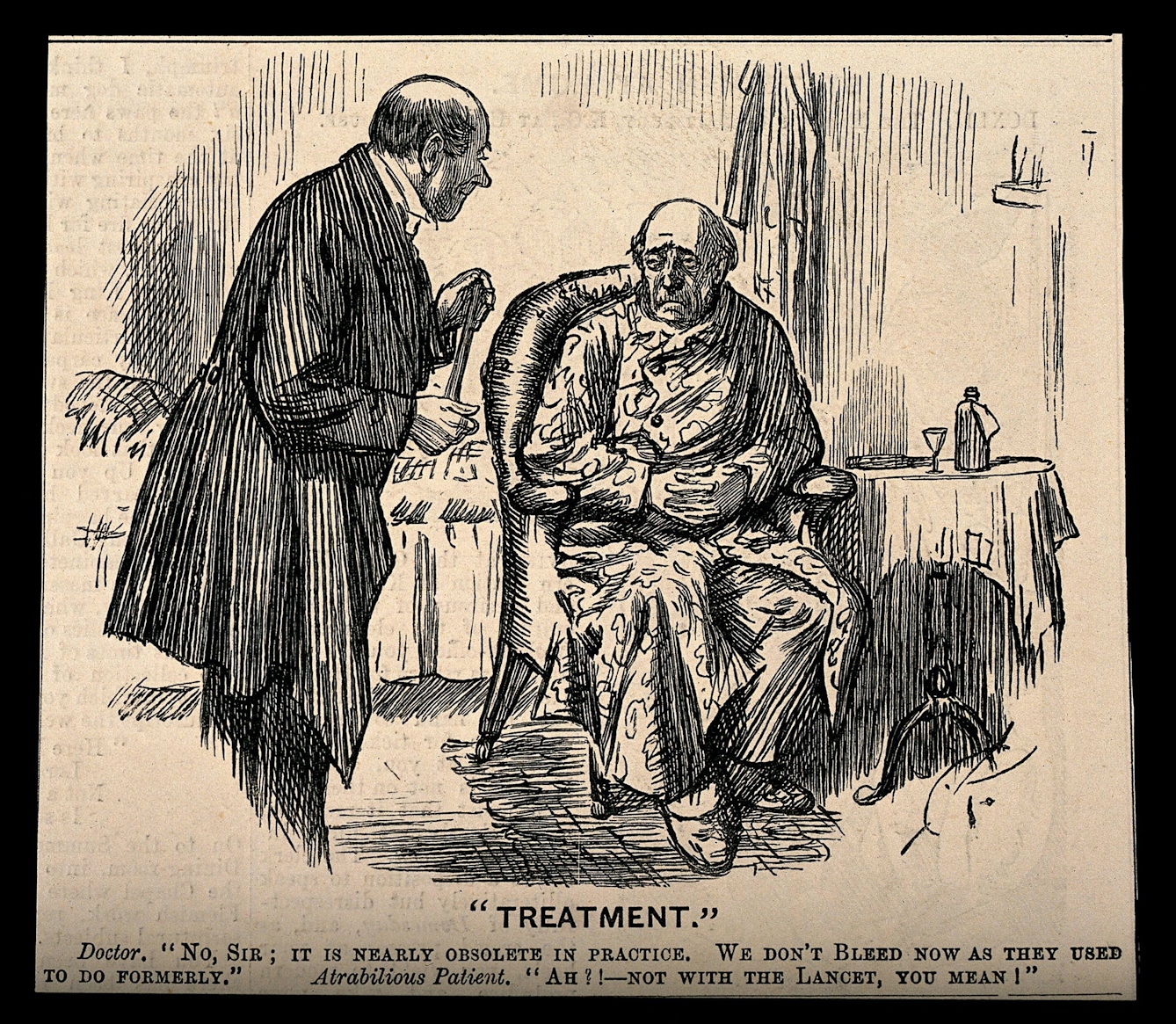

By the 19th century, bleeding was considered dangerous and no longer deemed ‘heroic’ cure-all medicine. Some patients, who had grown to expect it, may even have been disappointed.

Drawing blood today

Although inherently dangerous, traditional bloodletting might not have been as totally unhelpful as it might sound. Researchers found that letting blood may have been an effective mechanism for starving bacterial pathogens of iron and slowing bacterial growth, which would have been one of the only ways to achieve this in the pre-antibiotic era.

In the 21st century, we mostly only take blood in the form of phlebotomy, the ubiquitous diagnostic blood test, or from donors to enable blood transfusions. Leeches are still used to treat some nervous-system abnormalities, dental problems, skin diseases and infections. Leeches are also used in surgery because they secrete peptides and proteins that help prevent blood clots. So you may find that even today you could be “bleeding healthy”.

About the author

Julia Nurse

Julia Nurse is a collections research specialist at Wellcome Collection with a background in Art History and Museum Studies. She has a particular interest in the medieval and early modern periods, especially the interaction of medicine, science and art within print culture.