In the first two decades of the 2000s the NHS has been kicked around as a political football, and dogged by underfunding, strikes and scandals. But never before has it been so championed and beloved by the British people.

Born in the NHS

Cal Flynaverage reading time 6 minutes

- Serial

Today the vast majority of those living in the UK are no longer able to remember a time before the existence of the NHS.

The first baby born into the NHS, at one minute past midnight on 5 July 1948, is now 70 years old. Born in a cottage hospital in Glanamman, Carmarthenshire, Aneira Thomas was named in tribute to the health service’s founder, Aneurin Bevan, and her parents were saved the one shilling and sixpence fee for the midwife.

“My mother would introduce me as Nye, her National Health baby,” recalled Aneira later. “Up until the age of nine or ten, I really thought Aneurin Bevan was my father.”

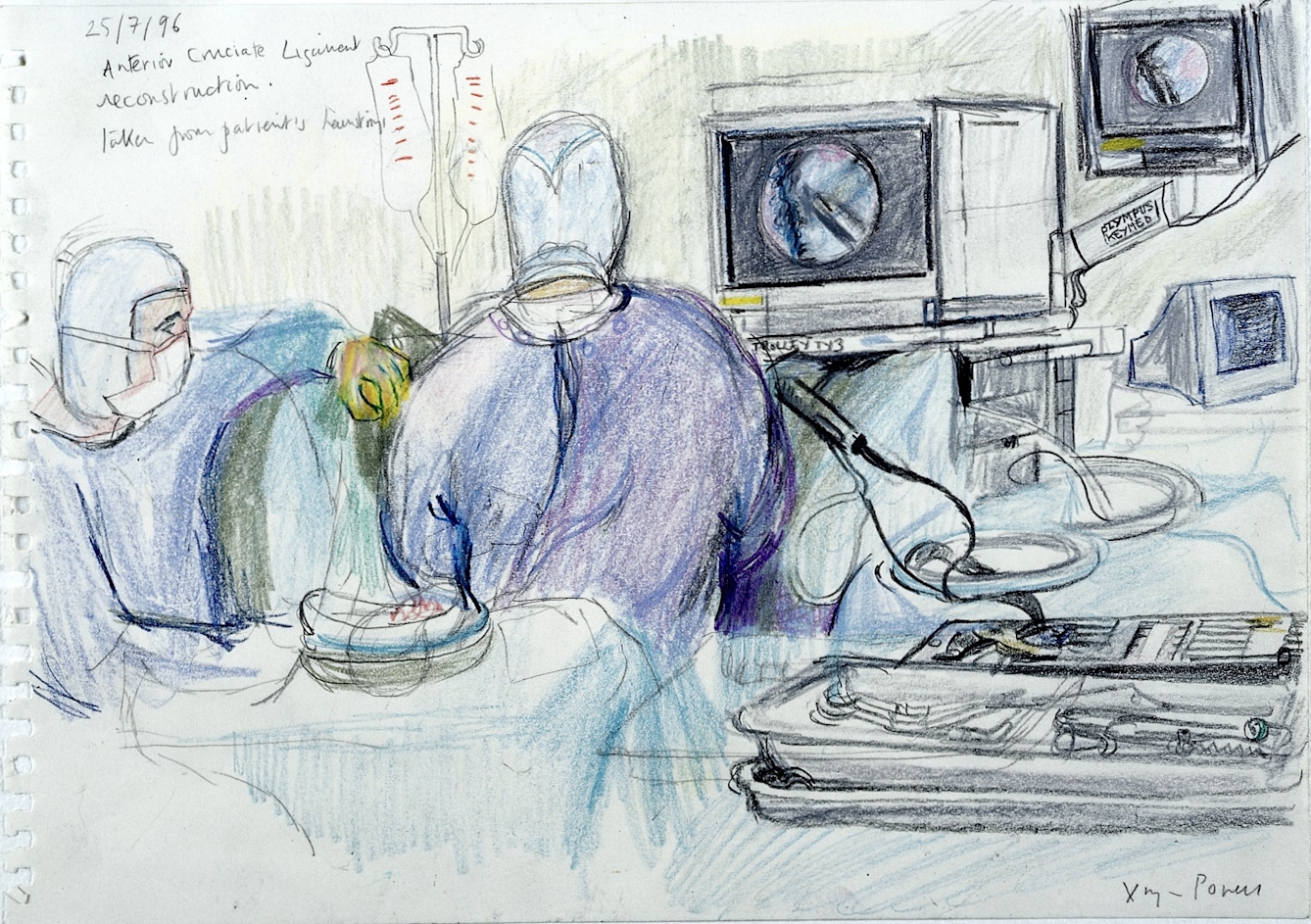

Over her lifetime, Aneira has seen remarkable advances in medical technology and treatment. In 1953, when both Aneira and the National Health Service were four years old, there was a major breakthrough when the structure of DNA was revealed for the first time by James Watson and Francis Crick; in 1958, polio and diphtheria vaccinations were made available to all children under the age of 15; abortion was made legal in 1968 when Aneira was 19; the first heart transplant took place later that year. She has seen the first test-tube baby born in 1978, the introduction of keyhole surgery in 1980 and the launch of the organ donor register in 1994.

Keyhole surgery, as depicted in this sketch of an operating room, was introduced in 1980 and is now regularly performed by NHS surgeons.

Aneira, like her four sisters, went on to work as a nurse, and ten years ago – aged 60 – she gave a speech at the Labour Party conference to celebrate the health service’s anniversary. She was “proud to be a little part of history”, she told delegates. She was certain, she added, that if her namesake could see how far the NHS had come, he would be extremely proud too.

The NHS in crisis

But it hasn’t all been smooth sailing, and never more so than in the last decade. Between 1998 and 2010 spending on the health service more than doubled in real terms, increasing at a rate of over 6 per cent a year; after the financial crisis of 2008, however, there has been a return to relative austerity following this time of plenty. While spending has continued to grow, it has increased by only 1.4 per cent a year.

Around the same time, a scandal in patient care came to light when the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust was investigated over unexplained levels of patient mortality. There, it was estimated that between 400 and 1,200 patients had died due to poor care in the trust between 2005 and 2009, and a later inquiry laid the blame upon a failure of leadership, cost-cutting and a “chronic shortage of staff, particularly nursing staff.” Several nurses were disciplined.

That initial estimate, which was based on projections, has been hotly disputed, but subsequent inquiries reported a litany of failings and cases of neglect: misdiagnoses; dirty wards; patients left unwashed, unfed and unable to use the toilet. The scandal had a serious effect on public trust, and the name ‘Mid Staffs’ has since become synonymous with state healthcare at its very worst.

Face of the nation

Nevertheless, when it came for Britain to host the Olympics in 2012, the NHS would take centre stage. Danny Boyle’s riotous opening ceremony featured many iconic figures from British culture – not least the Queen ‘parachuting’ into the stadium with James Bond, Rowan Atkinson as Mr Bean, and a cameo by Tim Berners-Lee, inventor of the World Wide Web – plus a two-minute long tribute to Great Ormond Street Hospital and the National Health Service, featuring 1,800 dancing volunteers dressed as mid-century nurses (including 600 real-life nurses) and pyjama-clad children bouncing on hospital beds.

Danny Boyle paid tribute to the NHS and GOSH at the 2012 London Olympics Opening Ceremony.

The ceremony was watched by an estimated 900 million across the globe – thus serving as a synecdoche of how Britain would like to present itself to the world. While prompting jubilation at home, the NHS segment provoked some bemusement overseas, where health services – state or otherwise – are not viewed with the same collective affection. As one “baffled” American journalist noted, it was “like a tribute to United Health Care or something”. One Russian commentator declared it “incomprehensible to non-Britains”.

But Boyle was unapologetic. “Everyone is aware of how important the NHS is to everybody in the country,” he declared to the press. “One of the core values of this society is that it doesn’t matter who you are, you will get treated the same in terms of health care.”

Political symbolism

The last time the UK had played host to the Olympics, in the summer of 1948, the NHS was only three weeks old. Much had changed – not least this new passion for the state-run health system.

It was visible again in 2016, as junior doctors once more returned to their picket lines – this time making their first all-out strike in history, with consultants manning the emergency wards. It became clear then that the conversation had shifted significantly from that of the 1970s: though the flashpoint was still the issue of pay and working hours, doctors now framed their argument as a defence of the service as a whole. The British Medical Association – the doctors’ trade union – declared that the new contracts were “an existential danger to the NHS”. Even those who worked for the NHS, while bearing serious grievances, now avoided questioning its values.

The NHS was invoked again as political ballast during the run-up to the EU referendum in 2016, infamously appearing on the side of a pro-Brexit bus that called for £350 million of the funds allocated to the EU to be directed instead to the health service – a proposal that was soon watered down. What’s clear is that to invoke a risk to the beloved NHS is a powerful way in which to mobilise public sentiment.

Faces of the NHS: 2000s & 2010s

Jenny Jones is a nursing student at Anglia Ruskin who will work for the NHS later this year, when she qualifies. Nursing is very rewarding, she explains: “Patients come in with broken bones... everything hurts and they don't want to do anything. Then you see them a couple of weeks later walking up and down the ward like ‘Look at me go!’ and it's great! You realise ‘I had a hand in doing that’, and I love that.” She is conscious of the pressures on the NHS but passionate about its importance: “People can be very quick to criticise the NHS today... [but] the service works… it’s under a lot of stress and a lot of pressure but it does the job and it looks after people at the end of the day.”

Ben Silverman was born into the NHS. His first memory of it was a good one: “I banged my elbow when I was about seven and had an X-ray… Everyone was very nice and understanding and friendly and it was a bit of an adventure in a way – and my elbow was fine!” He began work for the NHS in 2002, and is now a Consultant Anaesthetist at Harefield Hospital. He remains passionate about healthcare being free at the point of need: “I do still feel proud to work in the NHS. I think the underlying reasons why it was set up are still true... I do worry about its future sometimes… It’s a bit of a cliché that the NHS runs on goodwill but like most clichés there’s an element of truth in that.”

Sarah Itam, who is now a Urological Surgeon at UCLH, always wanted to be a doctor. She recalls: “I would always volunteer for health promotion initiatives in my local area... I found a picture of myself when I was about eight attempting to take someone's blood pressure!” She pursued this early ambition and joined the NHS in the late 2000s. On the challenges to the NHS today, she notes “Every era has its own challenges. You can see the various pressures throughout the decades... but the skillset within the NHS is good enough to deal with these and find solutions.”

Now, in 2018, the newspapers are again full of warnings of an NHS in crisis – of record demands, bed shortages and mounting debts. Still, says historian Jane Hand, a research fellow for the Cultural History of the NHS project, “there has always been a sense of the NHS being in crisis, and today is no different. To an extent, it is in times when the NHS is in crisis that we see the public really rally around it.”

The NHS has weathered a great many storms already over the past seven decades, and there will be plenty more to come. But its place in British hearts has never been more secure.

About the contributors

Cal Flyn

Cal Flyn is a writer and reporter from the Highlands of Scotland. She writes across the British press, including the Guardian, the Sunday Times, the Daily Telegraph, Prospect and New Statesman. Her first book, ‘Thicker Than Water’, was published by William Collins in 2016, and selected by the Times as one of the best books of that year.