We talk about feelings like joy, sadness, anger and fear all the time, but how do we tell what emotion a person is feeling? The biggest clue is the expression on their face. In the case of positive emotions like joy or happiness, a smile or laughter is often a big giveaway.

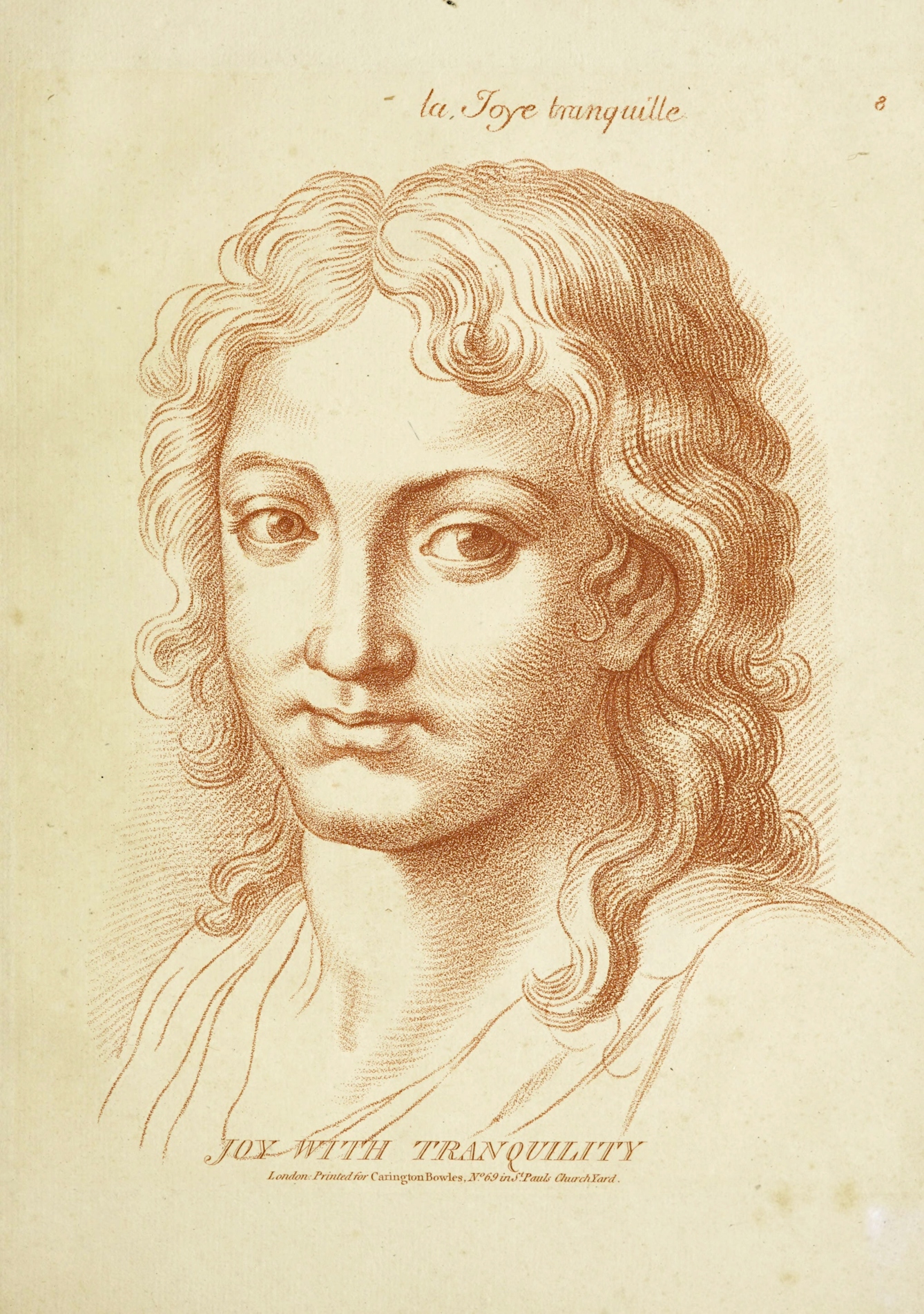

Several people have tried to match specific facial expressions to particular emotions over the years. The painter Charles Le Brun (1619–90) went as far as creating drawings that he believed showed the ideal expression for each emotion, such as “joy with tranquillity”.

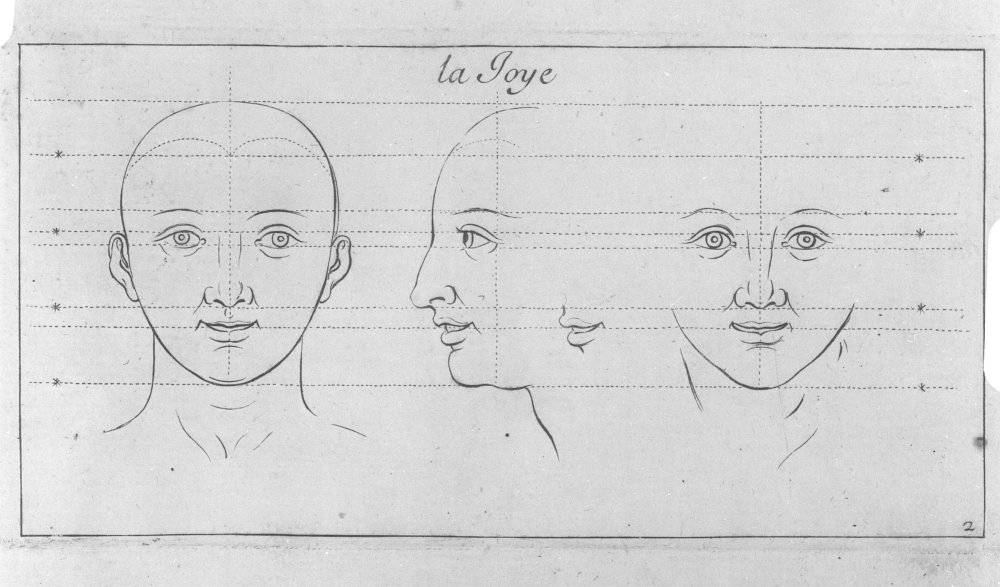

With the artist’s eye for detail, Le Brun observed that “Joy fills the soul... in this passion the forehead is calm, the eyebrow motionless and arched, the eye moderately open and smiling; the pupil bright and shining; the nostrils slightly open, the corners of the mouth a little raised, the complexion bright and the lips and cheeks ruddy”. After much careful study he produced a precise template for drawing a joyous expression.

As Director of the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture in Paris, Le Brun believed that the ultimate achievement in painting was to tell a complex story that could be read easily by the viewer. The story was told through the overall composition, the appearance of the people depicted and the expressions on their faces. One of the most difficult things for a painter to capture was the emotion in a fleeting facial expression. So Le Brun created templates for different emotional expressions, including joy.

Le Brun based his list of emotions on the work of the French philosopher René Descartes (1596–1650). In his treatise ‘The Passions of the Soul’, Descartes hypothesised that the soul was located in the brain, and that the passions (emotions) were the bodily expressions of the soul. Descartes listed six basic passions: wonder, love, hate, desire, joy and sadness.

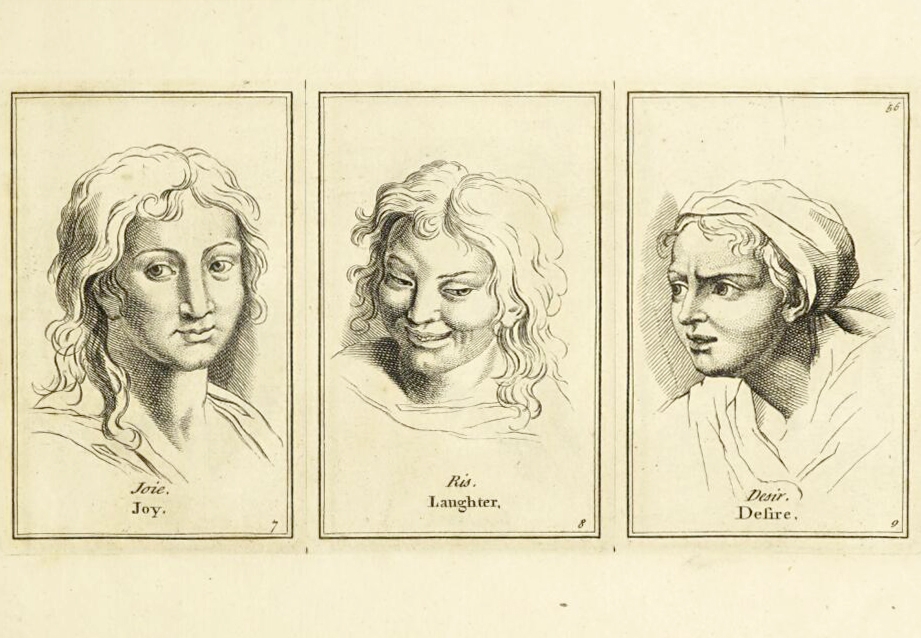

Le Brun’s ideas spread to art schools across Europe and influenced art practice for over 200 years. One artist who followed Le Brun’s guidelines was Antoine Coypel (1661–1722). In his work ‘Bacchus and Ariadne’, the reclining satyr has Le Brun’s expression for ‘laughter’, while the woman behind him expresses joy. But where Le Brun describes this expression as “joy with tranquillity”, the scene from classical mythology presented by Coypel is one of erotic pleasure rather than tranquil joy.

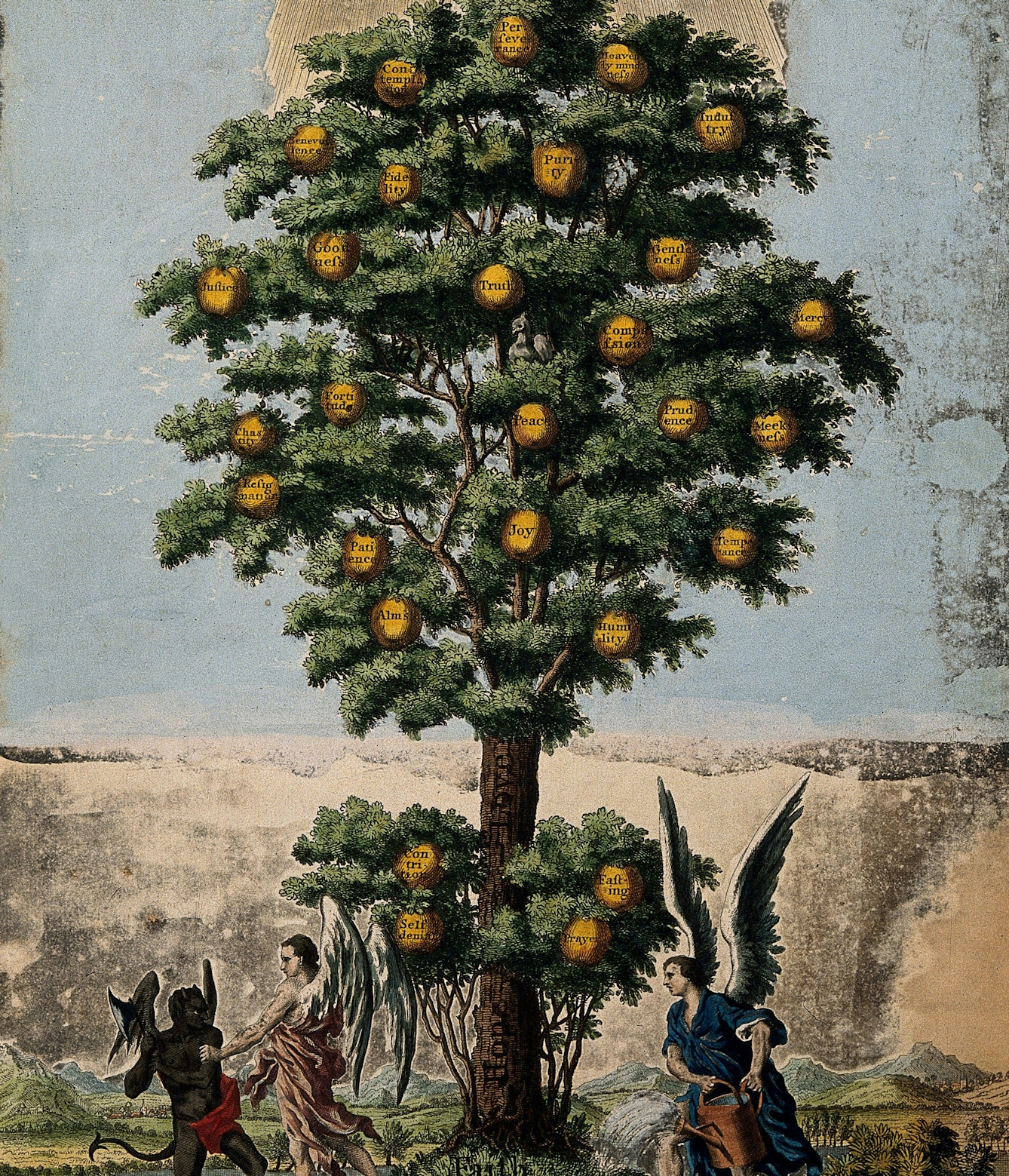

The ancient Greeks distinguished between two different positive emotional states. Aristotle (384–322 BCE) described eudaimonia – literally ‘good spirit’ – as a sense of flourishing or a life well-lived. Epicurus (341–270 BCE), on the other hand, described ‘hedonism’ as a more immediate form of satisfaction through pleasurable experiences. As this tree of life shows, joy is considered a Christian virtue closer to Aristotle’s view of something that comes from within and maybe this is what Le Brun meant by “joy with tranquility”.

Coypel’s depiction of joy suggests something closer to hedonistic pleasure – “the joy of sex”, perhaps. Joshua Reynolds’s (1723–92) portrait of Miss Emma Hart as a ‘bacchanate’ (a female follower of Bacchus, god of wine and religious ecstasy) also relates to a more hedonistic kind of joy. He writes admiringly of a classical “figure of a Bacchanate leaning backward, her head thrown quite behind her... it is intended to express an enthusiastic frantic kind of joy”.

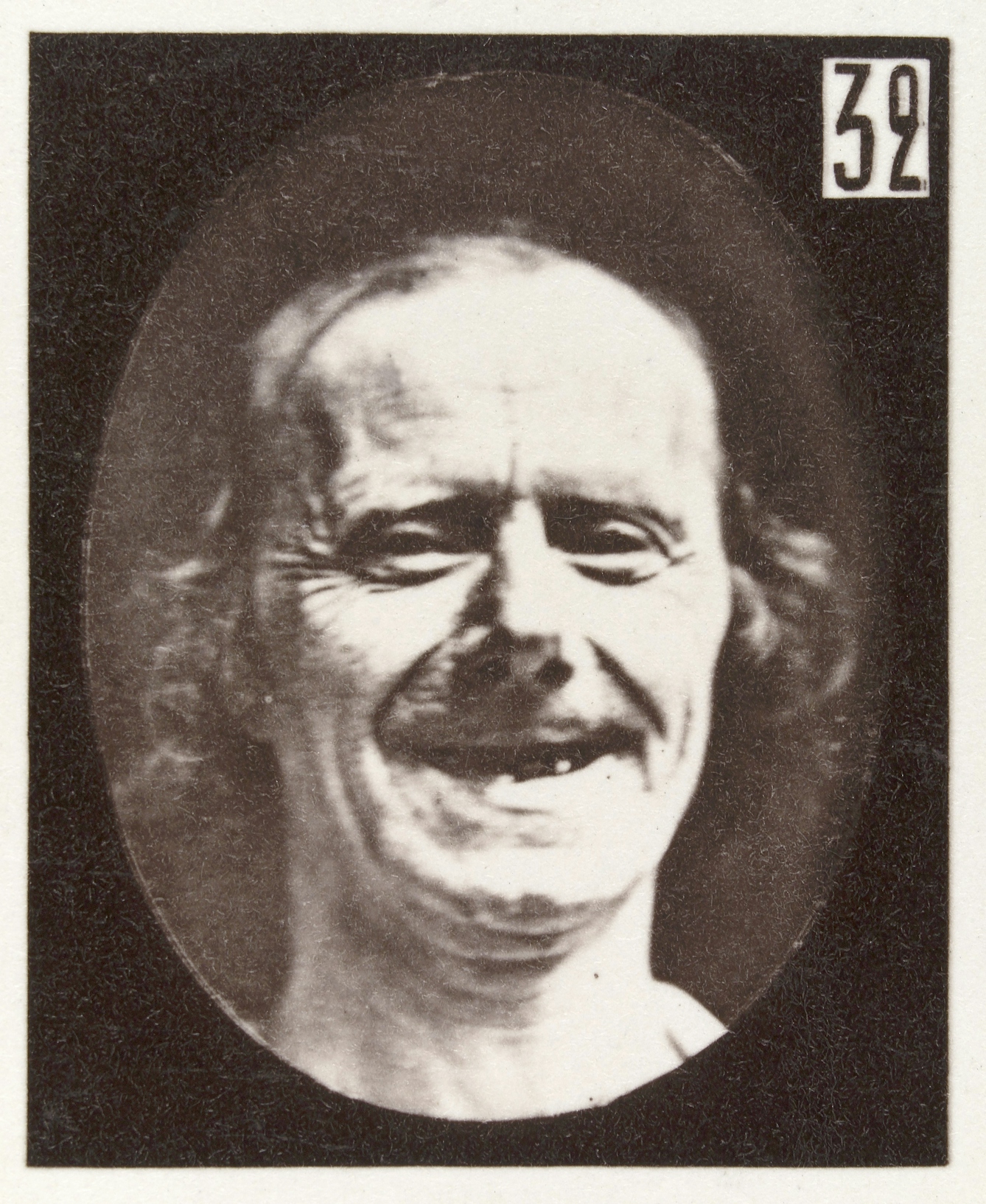

By the end of the 18th century, Le Brun’s templates were falling out of favour. As the systematic study of facial expressions declined in art, it was taken up by science in the form of the French physiologist Guillaume Duchenne de Boulogne (1806–75). Duchenne’s method was scientific, but he also intended his work to be an aid for artists. He used two technological innovations – electrical stimulation and photography – to help capture and characterise emotions through facial expressions. In his photograph showing ‘joy’, the expression is artificially created by electrically stimulating the facial muscles.

Duchenne’s photograph of laughter appears in a chapter on joy in Charles Darwin’s 1872 book ’The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals’. Darwin observes joy in both the face and the body and comments that it is often accompanied by “purposeless and extravagant movements of the body, and to the utterance of various sounds. We see this in our children when they expect a great pleasure and dogs which have been bounding about.” Many people, including Le Brun, had compared animal and human facial features, but Darwin was the first to suggest that certain emotions were universal, shared not only by people all over the world but also by animals.

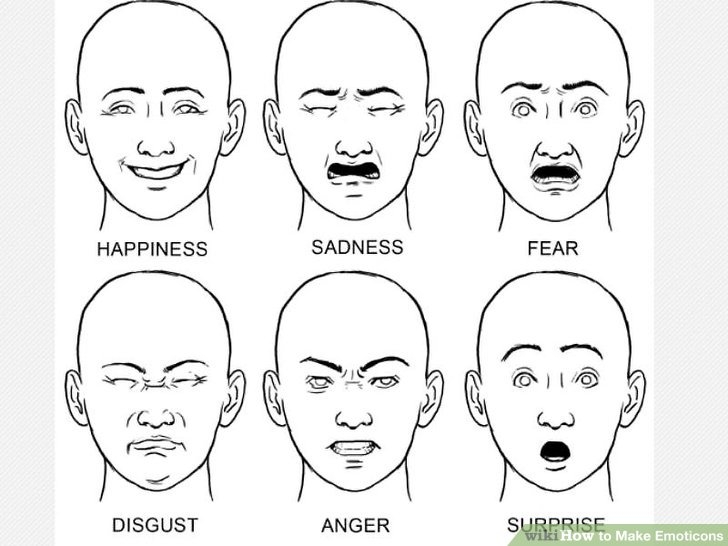

Darwin’s research was taken up by psychologists in the 20th century. In the 1960s, Paul Ekman and Wallace V Friesen showed pictures of Westerners with different facial expressions to isolated villagers in Papua New Guinea, and then asked them to identify the emotions expressed in the photographs. They found that six emotions appeared to be universally identifiable: fear, anger, disgust, joy, sadness and surprise. Today most researchers, including Ekman, believe that facial expressions play an important role in non-verbal communication between people, but the extent to which they are innate and universal or learned behaviours is still debated.

Emotional expressions help us to judge the appropriate response to someone’s behaviour. If we see signs of anger it’s a warning that things might escalate to aggression or danger. Conversely, a joyful or happy expression is like a welcome sign, signalling that someone is open to interaction. Maybe that’s why, of all the emotions, it is the positive ones of happiness and joy that seem to be most universally recognised.

About the author

Lalita Kaplish

Lalita is a digital content editor at Wellcome Collection with particular interests in the histories of science and medicine and discovering hidden stories in our collections.