Meat has been traded in Smithfield for centuries, but the market’s upcoming move east is simply another step in its long history of reinvention. Tom Bolton explores how this area, just north of the City of London, has been in a state of flux for at least 900 years.

Fairs, fires and the future of Smithfield

Words by Dr Tom Bolton

- In pictures

The first mention of a “smooth field” where “fine horses”, “swine with their deep flanks, and cows and oxen of immense bulk” were traded came in 1174 from William Fitzstephen, a clerk who once worked for the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas à Beckett. The market was held just outside the city walls on open ground close to where the main road from London to the north began. Until the 19th century, the distance between London and Edinburgh was measured from Hicks Hall, a courthouse at the bottom of St John Street, close to Smithfield.

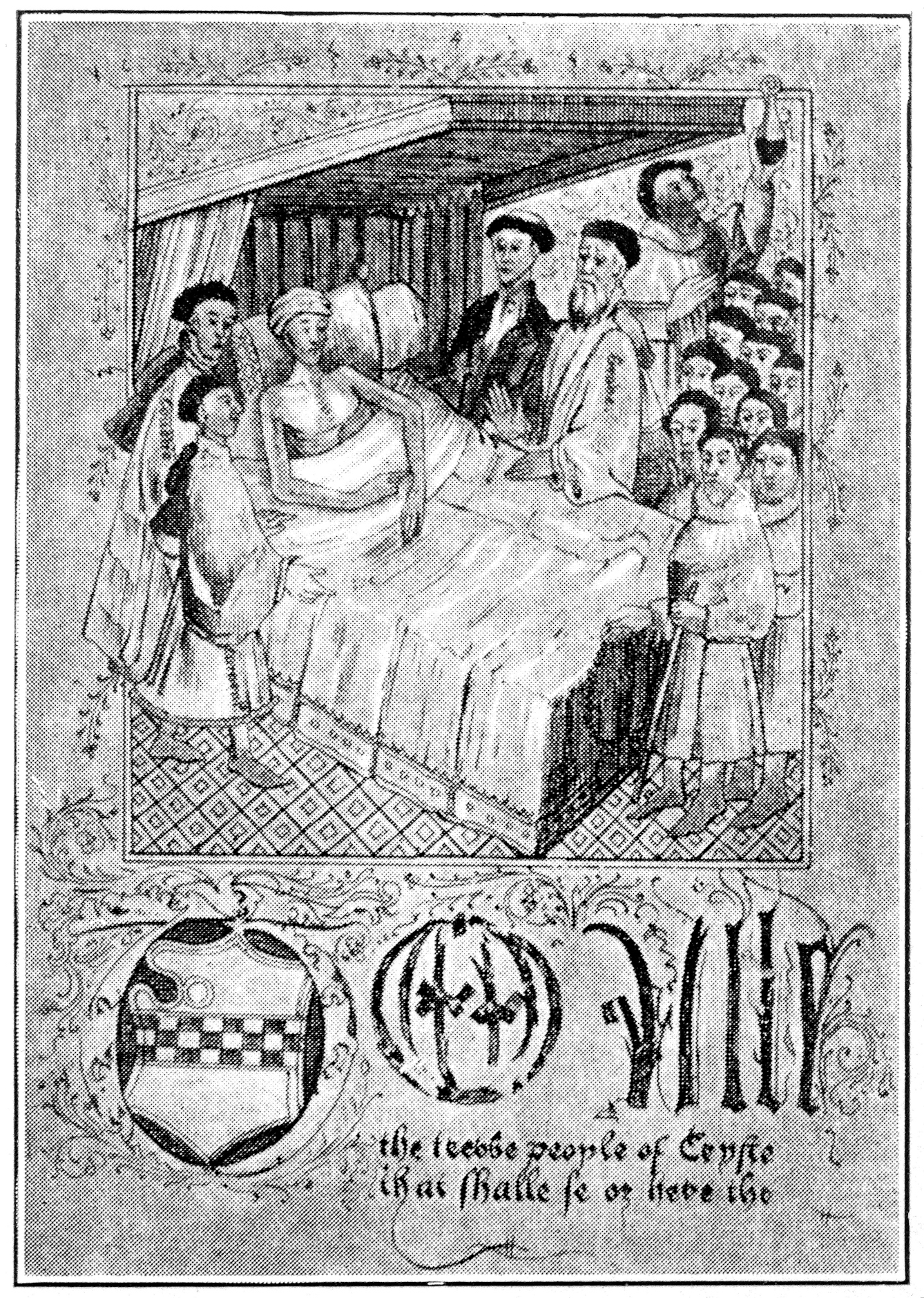

Smithfield has been home to a hospital for centuries, too. Rahere, a monk and favourite of Henry I, founded the Priory of the Hospital of St Bartholomew here in 1123. The monk was inspired, it was said, by a vision that prayers for healing would be heard in this place. The priory, ancestor to the modern-day St Bart’s Hospital, was set up with a “charter of privileges” from King Henry. This charter also covered the Bartholomew Fair, a trade fair for cloth merchants. London’s main horse fair, the Friday Market, was held here too, and so Smithfield’s trading history began.

The juxtaposition of healing and death at Smithfield was stark. Outside the walls of the priory lay not only the meat market but also the London gallows. Before public executions moved to Tyburn in the 1400s, they took place at the Elms, on the Smooth Field. Scottish rebel leader William Wallace met his end here in 1305, as did Roger Mortimer, killer of Edward II. In 1381 Peasant’s Revolt leader Wat Tyler was stabbed to death at Smithfield in front of the boy king, Richard II, in a fight with the Lord Mayor of London and his men.

According to ‘The Mystery and Lore of Apparitions’ by C J S Thompson, the Smithfield Ghost was said to appear every Saturday evening between the hours of nine and midnight, amusing itself by pulling joints of meat off butchers’ stalls. Thompson quotes an account from 1654 that explains, “Many have ventured to strike at him with cleavers and chopping knives, but cannot feel anything but aire.” It’s unclear whether people really believed in the Smithfield Ghost, one of London’s lesser-known apparitions, or if it was invented for political reasons by the pamphleteer John Crouch, the author of that 1654 account.

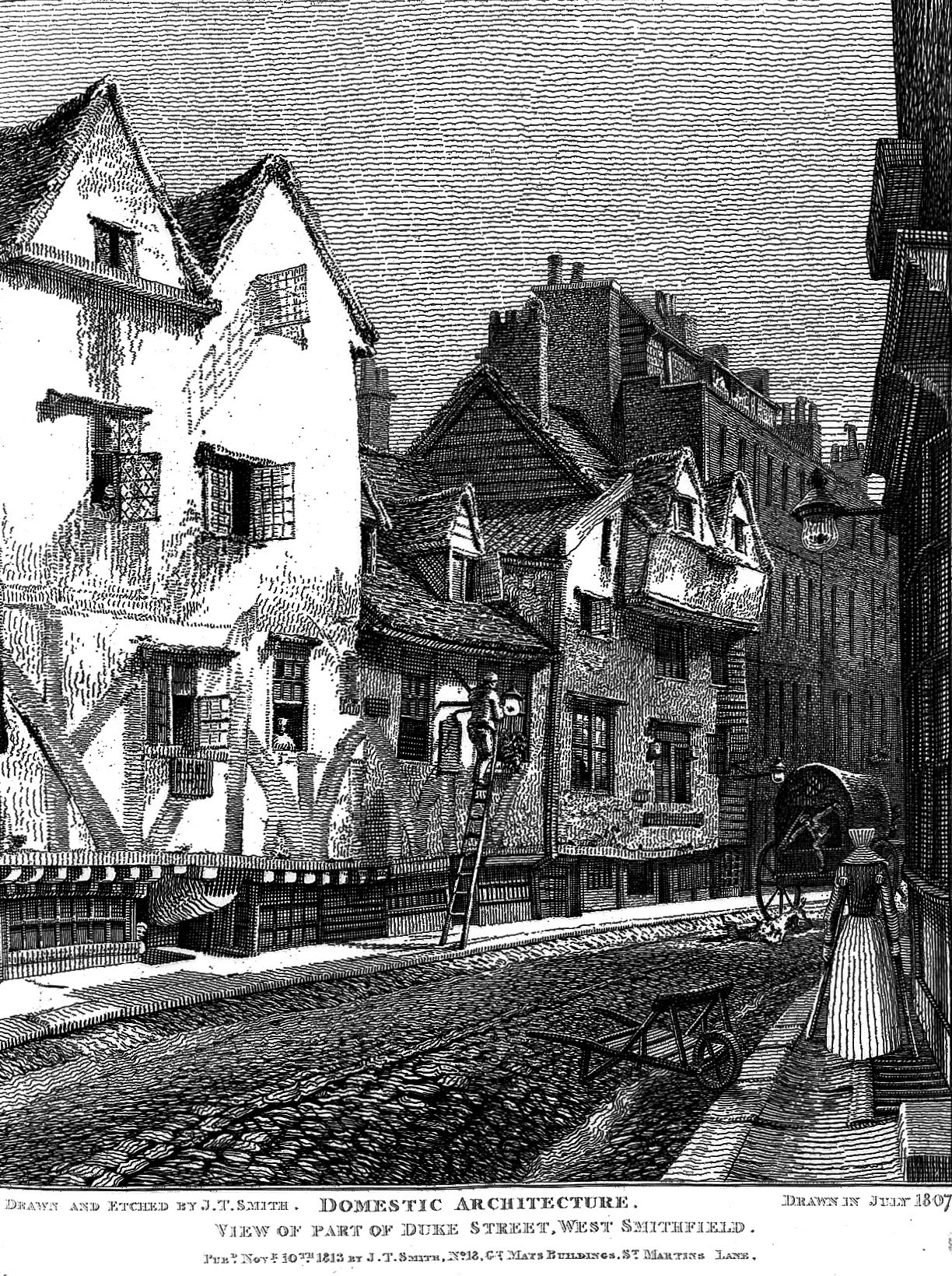

Located close to the city gates, Smithfield was a natural spot for transient, dubious and illegal activities. One of its several brothels was run by George Wilkins, the playwright who collaborated with William Shakespeare on ‘Pericles’. Smithfield’s poor reputation lasted through the 19th century, when the area was popularly known as ‘Little Hell’. The slum streets (in the valley of the now-buried River Fleet) have been fixed in the popular imagination by Charles Dickens as the territory of Fagin and his pickpockets in ‘Oliver Twist’.

The Victorians made frequent attempts to modernise the chaos of their fast-growing city. The ancient practice of live slaughter at Smithfield, with sheep, pigs and cattle driven through the streets to the local ‘shambles’ or slaughterhouses, ended with the 1852 Smithfield Market Removal Act. A new Metropolitan Cattle Market was built out of town, on the Caledonian Road. Some foresaw disaster. In her book about London’s Old Caledonian Market, Marjorie Edwards explains that one drover warned, “Mark my words – we may take Sebastopol, but we’ve lost Smiffield and it’s up with the British nation.”

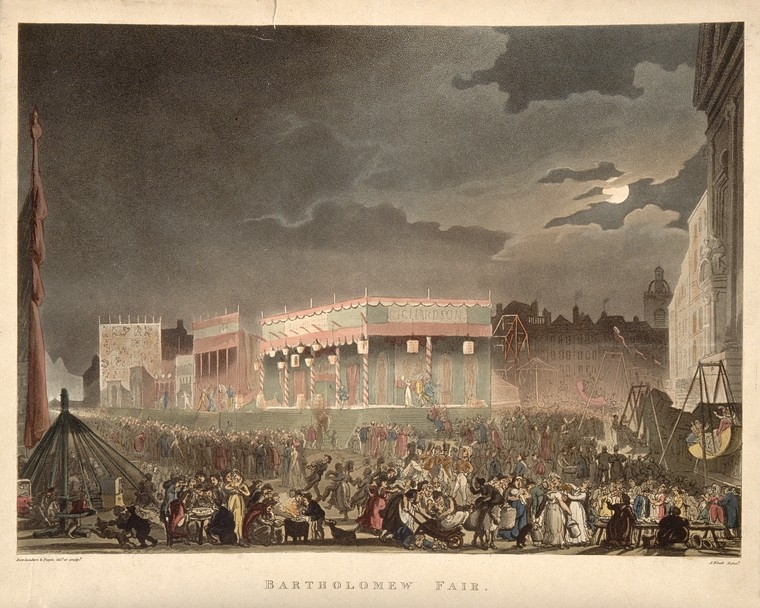

Victorian London also saw the end of the Charter Fairs, entertainments that had grown out of the royal charters for markets. Bartholomew Fair, held at Smithfield each year at the start of September, was the most notorious of all these gatherings. It was immortalised as early as 1612 by the playwright Ben Jonson as a true carnival, where thieves and Justices of the Peace rubbed shoulders, social rules were suspended and, perhaps, everyone emerged the better for it. But the Corporation of London abolished it in 1855, keen to end the public disorder that was part of its appeal.

With Bartholomew Fair gone, the clean-up could really begin. In 1860, the Corporation of London agreed to build new, modern market buildings at Smithfield to centralise meat sales. Smithfield was not the only wholesale meat market in the area. Newgate and Leadenhall Markets were also popular, particularly for pork and poultry. The authorities were keen to close Newgate and clear the crowded streets around Old Bailey, where, according to Bradshaw’s ‘Handbook to London’ (1862), “no one could pass without being either butted with the dripping end of a quarter of beef, or smeared by the greasy carcase [sic] of a newly slain sheep”.

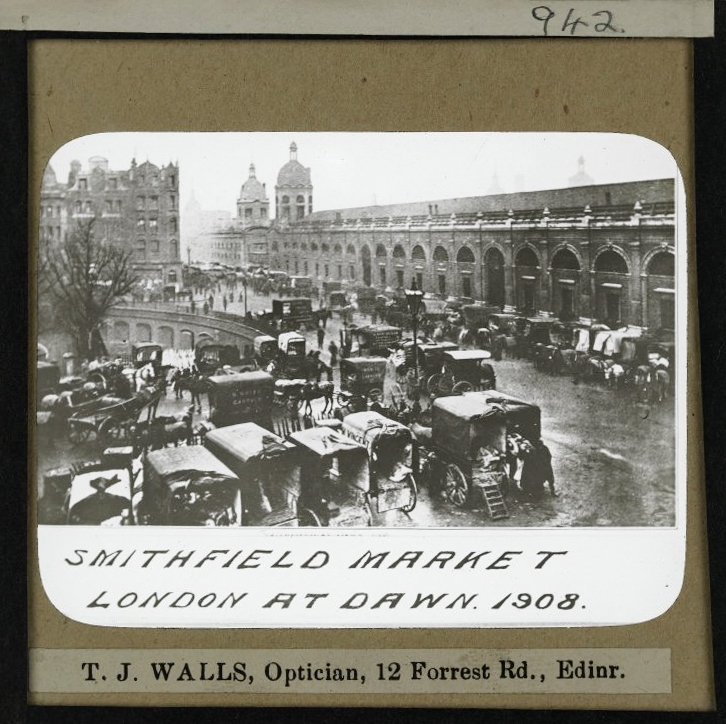

The tangle of narrow streets that had surrounded the Smooth Field, including Chick Lane, Cow Lane, Duck Lane and Field Lane, were cleared, and the slums, for the most part, were swept away. The grand London Central Markets buildings, designed by architect Sir Horace Jones, opened in 1868. Smithfield was expanded several times – the Poultry Market opened in 1875, the General Market in 1883, and the Fish Market and Red House Cold Store in 1888. This image shows how the market looked by 1908.

World War II began the market’s slow decline. The Fish Market was damaged by bombs and never reopened. In 1958 the Poultry Market, with its turrets and cockerel weathervanes, burned down in a spectacular fire. However, this disaster opened the way for something special: a new Poultry Market opened in 1963, a T P Bennett-designed structure with one of the world’s largest concrete domes. It is now empty but has a Grade II listing.

The decline of small industries gave the area a run-down feel in the 1990s, when Smithfield became known for its nightlife. Empty warehouses were ideal for club nights, especially because the market pubs operated as ‘early houses’, serving drinks and huge breakfasts from 7am for all-night market workers. Butchers and staff from Bart’s Hospital mixed with party people at morning opening. Fabric, a London institution, is the sole survivor from the clubbing years.

Change has been coming for some time. The General Market, Fish Market and Red House buildings have lain derelict for decades. In 2008 they narrowly survived an attempt to redevelop them as generic offices after a conservation campaign led by SAVE Britain’s Heritage. Now the Museum of London is set to relocate to West Smithfield, reflecting the close connections between this area and London’s identity, and the meat market will move to Barking in east London. What happens to the remainder of the market remains to be seen, but after the current government restrictions are lifted the Fox and Anchor should be open for pints at first light again.

About the author

Dr Tom Bolton

Dr Tom Bolton is a researcher, and the author of five books, including ‘London’s Lost Rivers Volumes 1 & 2’, ‘Low Country: Brexit on the Essex Coast’ and ‘Vanished City: London’s Lost Neighbourhoods’. His work has been published in the Guardian, the Daily Telegraph and Londonist.