Sedra Al-Yousef was 14 and living in Syria when her father’s life was threatened by government forces. Seven years and thousands of kilometres later, she is on the brink of a bright future in medicine, informed by deep compassion and insight from her experiences as a refugee.

Fleeing fear, defying prejudice

Words by Sedra Al-Yousefaverage reading time 8 minutes

- Article

Insecurity, nervousness and fear. These were the emotions that flooded my 14-year-old self as I packed to leave the city I’d always called home. That night, I had only two hours to collect my memories, books and other essential stuff in boxes before fleeing our home in Aleppo and heading to Damascus.

Until that night, my life had always been peaceful and secure. I loved following my dad to his dental clinic and spent hours watching how he treated his patients with patience and compassion. I looked forward to the day I could begin treating my own patients in the same way.

Fast forward to that fateful night. My dad, who was also a member of the Syrian parliament, had spoken out against the murder of thousands of innocent civilians at the beginning of the war in Syria. He had been receiving death threats from President Assad’s forces for a couple of weeks, and then the threats turned into reality when these forces burned down his clinic. That night, we left Aleppo for a new life in Damascus, a life I hadn’t chosen, but one that had chosen me.

More: Novelist JJ Bola reflects on the difficulty of finding belonging in Britain as a refugee.

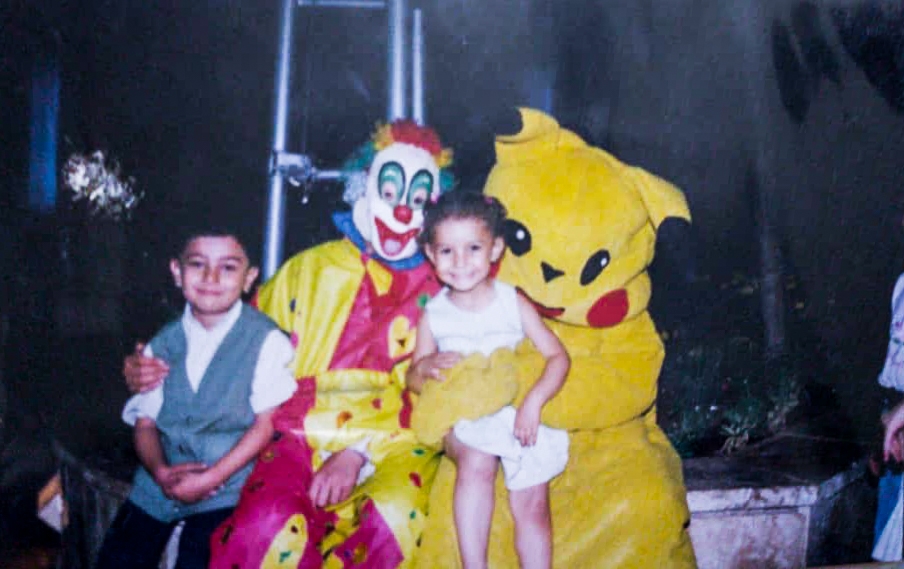

Sedra as a young girl in Syria.

My nostalgia for my first home, school, and friends grew with each day, and two months before my 9th-grade national exams, my dad had to flee again – this time alone and on a longer journey to Denmark. A year later, my mother, brother and I finally made the trip to join him. In Denmark I not only had to learn a new language at 16, I also had to construct a new identity bold enough to handle survival in a foreign society.

Reuniting with my dad was the happiest thing that had happened to me in a year. However, while driving towards our new home, I knew that there would be no way back to Syria unless the war ended. Deep inside me, I knew that the situation in Syria was only getting worse and more complicated.

A new chapter in my life

A few weeks later, I didn’t feel that learning Danish was simply like learning any new language: it was the first chapter of a whole new book of my life. It was about knowing myself: my strengths, my weaknesses and how to communicate with my new society. Meanwhile, I lacked the feeling of being understood, so I threw myself into mastering the new language. After six months I didn’t just graduate from language school, I also started working as a translator helping other refugees adapt to their new lives. I always got motivation from my passion to start studying medicine so I could become a surgeon.

At the same time, in language school, I found myself in an unsupportive local community. I was informed that my education from Syria wouldn’t be recognised in any Danish high school, and that I had to start at a Danish school with students who were three years younger than me because – as they told me at the time – “not even a Dane can make it to a medical school in a short time, so how would a Syrian who just fled to the country be able to do so!”

I missed the simple way of life where our neighbour would knock on the door and join us for a coffee without complicated plans. There are no formalities with people you love in Syria.

At that time, my nostalgia for home and Syria was only growing. I missed the small details in my life in Syria that I had taken for granted. I missed speaking and expressing myself without having to formulate my feelings in another language. Saying what was on my mind without worrying about being misunderstood due to cultural differences. I missed family gatherings on our small balcony in Aleppo and observing the crowded streets below.

I was still living with my family in a tiny village in southern Denmark. People there go to sleep too early and work the whole week. They don’t sit on the balconies as we did, and at eight o’clock all the streets would be as empty as a city of ghosts.

Sedra at her graduation ceremony in Denmark.

I missed the simple way of life where our neighbour would knock on the door and join us for a coffee without complicated plans. There are no formalities with people you love in Syria. Nobody cares that their home is small when guests are sleeping over or when family gathers together. Some even sleep with sheets and blankets on the floor and everyone is simply happy.

There was a spontaneous way of living that I knew for sure I wouldn’t be able to find anywhere other than Syria. I was a teenager, but I felt like an adult teenager who was reflecting on these memories and trying to see the light in what was coming next.

At that time, war was accelerating in Syria. A big part of my family was still there. My parents and I were mentally with them all the time. When the language school was complaining about the fact that my parents’ language skills weren’t noticeably progressing with time, my parents were spending whole evenings trying to get any sort of connection with the family inside Syria and watching the Syrian news, following where the next bomb was being dropped.

It wasn’t easy for me to make friendships in my new school. I missed my friends in Syria. I missed chatting about our everyday problems, our plans for the future, and how we would attain our dreams. In Denmark everything seemed different, and the teens’ daily problems were very different from mine. Partying and drinking was a major part of their free time.

I was missing my family, although the fact that I was able to flee with my parents without losing any of them in Syria or on the way to Denmark felt a blessing – a great blessing that no one around me could understand.

How populism dehumanises refugees

During that time, the populist media, both in Denmark and Europe, was playing a major role in making the divide between ‘us’ and ‘them’ much bigger. The way refugees were presented as a mass of people moving into Europe, without highlighting their stories or their humanity, contributed to dehumanising them in their new communities.

I started reading more about populism and how it affects people’s approach to the refugee crisis, and then came across a foundation in Berlin that offered travel funds for projects on populism in Europe. I applied and was among 30 young people from across Europe who received funding. I travelled to Italy, Germany, Luxembourg and Austria.

Through my travels, I tried to reach out to local people, whether in the streets, cafés or in hostels, and talk to them to find out how they thought the media in their country shaped their perception about refugees. I also conducted a lot of interviews with Syrian refugees and was overwhelmed by how similar our stories were. I’m still in touch with many people I met during my travels.

Sedra working as a medical student at Copenhagen University.

Back in Denmark, I was interviewed by a high-school principal in a town near our home. It was the first time since we left Syria that I’d spoken to an encouraging person in my community who wasn’t from my family. He believed in me and insisted that I had to start at his school. I suddenly found myself taking A levels in a completely ‘blond school’. I was the first refugee to go there.

Doing A levels in a new language after a few years in Denmark wasn’t a piece of cake. However, the feeling of having someone who believes in you all the way made a big difference to me as a 19-year-old who had already gone through a mental breakdown.

Two years later, I graduated from my school, ranking one of the highest averages in the country, and qualified to enter the Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences at the University of Copenhagen. It has been the first step on the road that I always aspired to go down. However, the feeling of not being understood, not being good enough and not fitting in introduced me to the importance of empathy in our lives as humans.

Putting myself in other people’s shoes has become very meaningful for me – I probably wouldn’t have been able to do it if I myself hadn’t gone through the process of not being understood. This has also given me a new perspective through which I see my future medical career: a perspective that doesn’t only focus on my skills as a surgeon who wants to save human lives, but also understands the language of empathy before any other language.

Today, believing in this compassionate view of humanity in this chaotic life we all live in, is what keeps my 21-year-old self balanced and hopeful.

About the author

Sedra Al-Yousef

Sedra Al-Yousef is a 21-year-old Syrian refugee living in Denmark. She’s a medical student at Copenhagen University and also works as a translator and mentor for other Syrian refugees.