Hookah smoking began in the royal courts of Mughal India, and like many other local customs, it was readily adopted by British colonials in the 18th century. But as Baijayanti Chatterjee explains, the hookah was much more than a smoking habit in Old Calcutta society.

Hookah smoking in colonial Calcutta

Words by Baijayanti Chatterjee

- In pictures

The hookah (from the Hindustani word huqqa) is a device used for smoking tobacco filtered through water. The tobacco is often flavoured or sweetened with honey and spices to make the smoke more palatable. Reflecting its long history, the hookah goes by many other names, including shisha from the Turkish, qalyan or nargil from the Persian and hubble-bubble from British colonial India. The origin of the hookah is contested, but the story goes that in 1604 an emissary of the Mughal Emperor Akbar (1542–1605) returned to court with some tobacco leaves and pipes, probably introduced by Portuguese merchants. But the emperor’s personal physician, Abul-Fath Gilani, was concerned about the effects of smoking tobacco and devised the hookah as a way to filter the smoke.

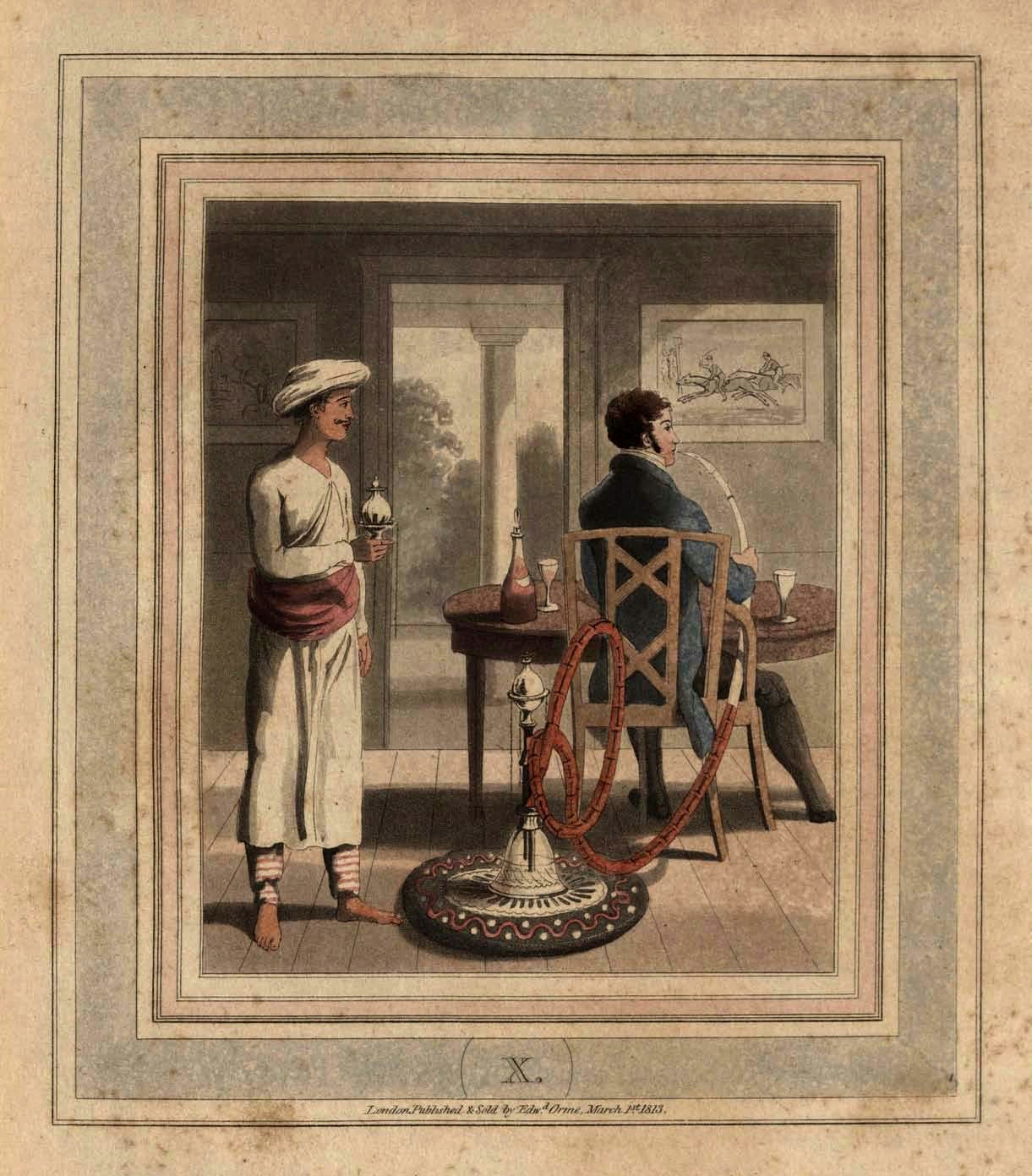

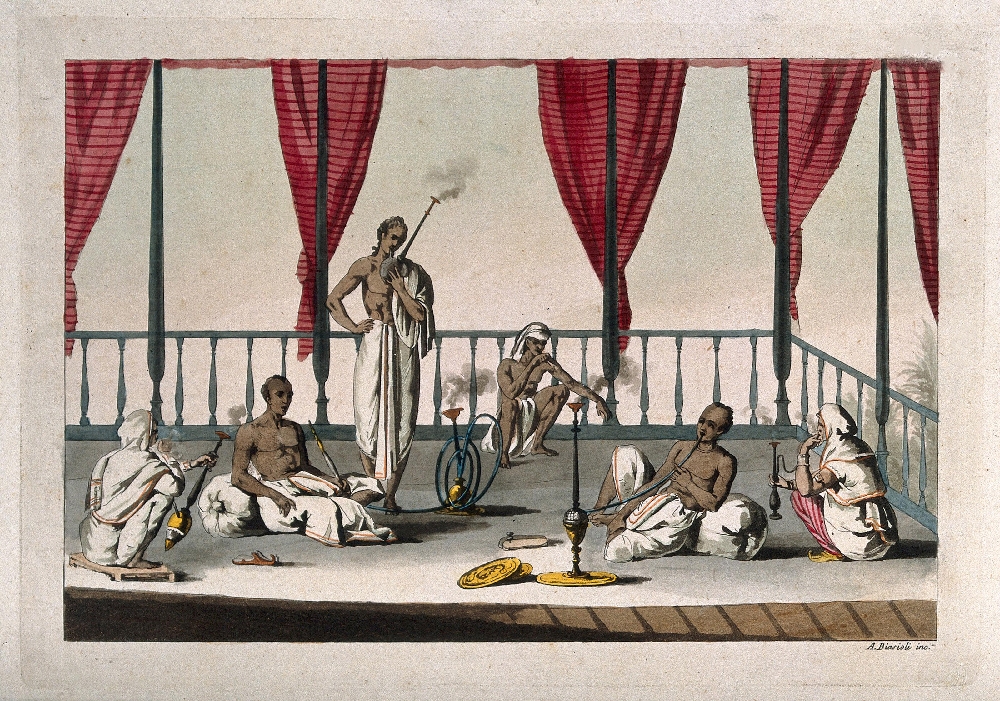

Both the Mughal emperors of India and the Safavid kings of Persia were great connoisseurs of the hookah, and the habit became a part of everyday life in the Mughal courts. Although tobacco smoking was prohibited for a brief period during the reign of Akbar’s successor, Jahangir, by the rule of Shah Jahan, Akbar’s grandson, it was revived, and hookah smoking spread widely throughout Indian society. Because of its association with royal culture, it developed its own etiquette and rituals, including a dedicated servant – the hookah burdar – who prepared the hookah for smoking and attended his master while it was being used. The mat carried by the hookah burdar was placed under the hookah.

In the 18th century the British began to colonise India on a large scale. From the mid-18th century, a new class of colonist emerged: the wealthy merchants of the British East India Company (disparagingly referred to as ‘nabobs’) who aspired to the aristocratic status of the gentry back in Britain. Historian T Spear suggests that: “From this Indian gentry with their wealth and ostentation, their retainers... [the British] acquired the tastes and habits which marked the ‘nabob’.” And because “a hookah was more expensive than a pipe and required a hookah bardar [sic] it would naturally come into fashion with increasing wealth and ostentation”. The last quarter of the 18th century also saw the arrival of many more civilian officials from Britain: tax collectors and administrators who fraternised with the local nawabs (aristocracy) and Indian landowners.

The hookah soon became an essential part of most colonial social gatherings. William Hickey, a young lawyer, arrived in Calcutta in November 1777, planning to join the British East India Company. In his memoirs he recalls being presented with a “highly dressed and splendid hookah” at several of the dinners he attended. Hickey didn’t take to the hookah and wondered if it was an essential part of Calcutta life, only to be told, “Here everybody uses a hookah, and it is impossible to get on without.”

So indispensable was the hookah, according to the reminiscences in ‘Echoes of Old Calcutta’ that “it was admitted to the supper-rooms, card-rooms – even to the boxes in the theatre and between the pillars and walls of the assembly rooms”. As with the Mughal courts, a hookah-smoking etiquette emerged. Women as well as men smoked the hookah, and it was said: “the highest compliment [a lady] can pay a man is to give him preference by smoking his hookah”. Of course, the gentleman would present his pipe to her with a fresh mouthpiece.

In the Mughal tradition, every European gentleman of consequence had his own hookah burdar, whose salary ranged from six to ten rupees monthly. In 1779, the British Colonial Administrator of Fort William (Calcutta), Warren Hastings and his wife Marian hosted a “concert and supper at Mrs Hastings’ house in town”. A postscript on the invitation card asked guests to bring their own “huccabadar”. When he visited Bengal in 1789/90, French army officer Louis de Grandpré attended such a gathering, where all the hookah burdars came in together with the dessert course, each carrying his master’s hookah and for the next half an hour, conversation subsides as smoking begins. "A stranger" he recollects, "if he has not his hooka he will find himself in an awkward and unpleasant situation."

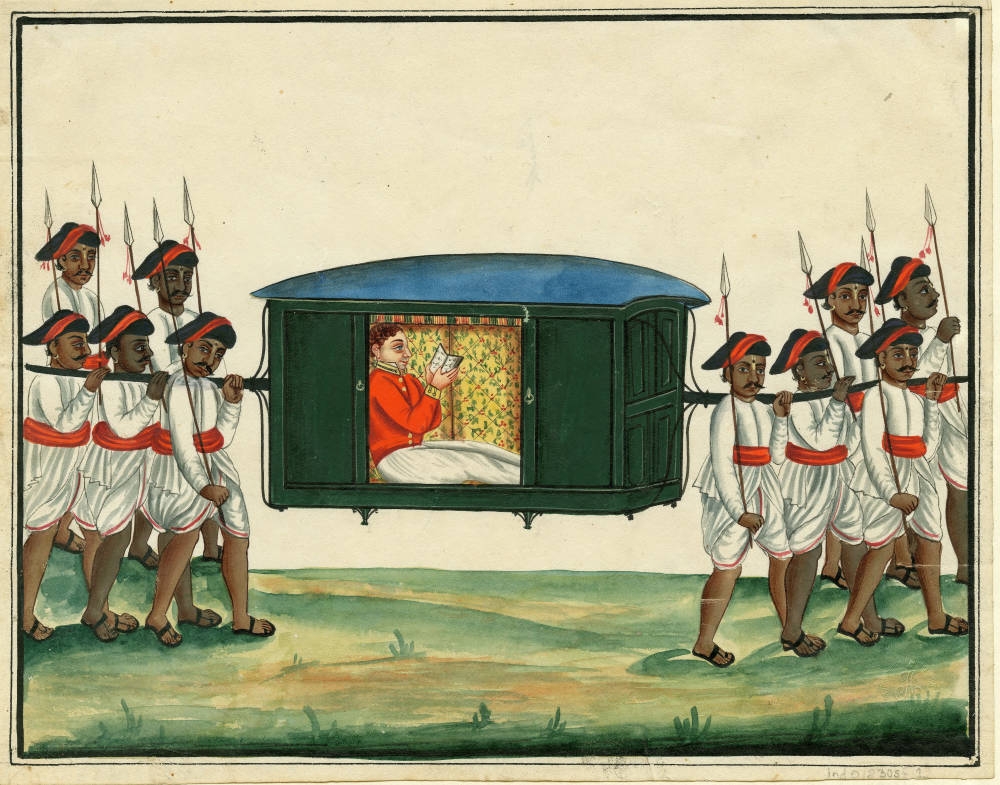

In addition to accompanying his master to all social engagements, the hookah burdar would walk beside his master’s palanquin or horse, should he wish to smoke while travelling or riding. This was a custom acquired from the Mughals and other local gentry. The hookah burdar carried the bottle and a “chasing-dish”, while his master held the end of the serpentine pipe. “In this manner,” according to Grandpré, “the hookah burdar kept up with the horse or the bearers of a palanquin without causing least inconvenience” to his master, who “smokes as commodiously as in an apartment”.

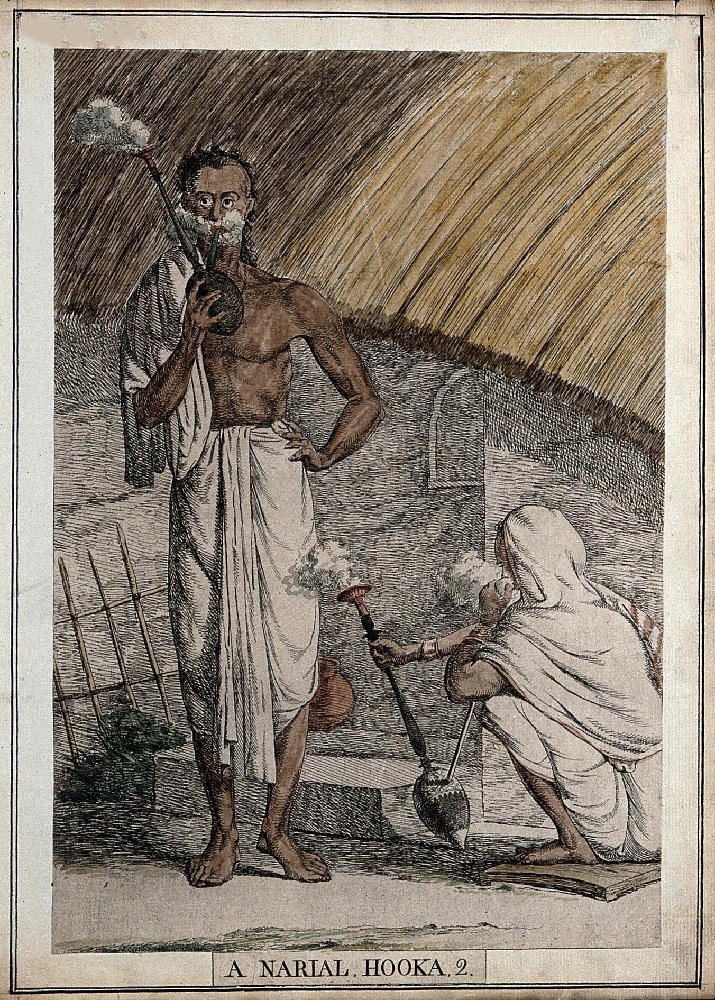

The habit of smoking the hookah was not limited to elite Indian and colonial communities in Calcutta, and as the practice proliferated, so did the many forms of hookah. In Bombay, hookahs were known in the mid-17th century as “cream cans” after the Persian ruler Karim Khan Zand, who popularised this particular variety. In Calcutta a small hookah for the palanquin was known as a “googoory”. A form of hookah widely used in Bengal was the narial or nargil (from the Sanskrit word for coconut), in which the glass water receptacle was replaced by a coconut shell.

The craze for the hookah among British colonials had declined by the 19th century. In 1802 one Major Blakiston complained that hookahs were too expensive to be afforded by many officers, because they required a hookah burdar in addition to the cost of the hookah and the tobacco. In 1822 a correspondent to the Calcutta Journal drew attention to the annoyance caused to ladies and others by the habit of hookah smoking and suggests that “his letter be printed once a month till the custom be banished from society”. ‘Hobson-Jobson’ – an Anglo-Indian dictionary – noted that in 1840 the hookah was still common at Calcutta dinner tables, but by 1878 its consumption was no longer in vogue.

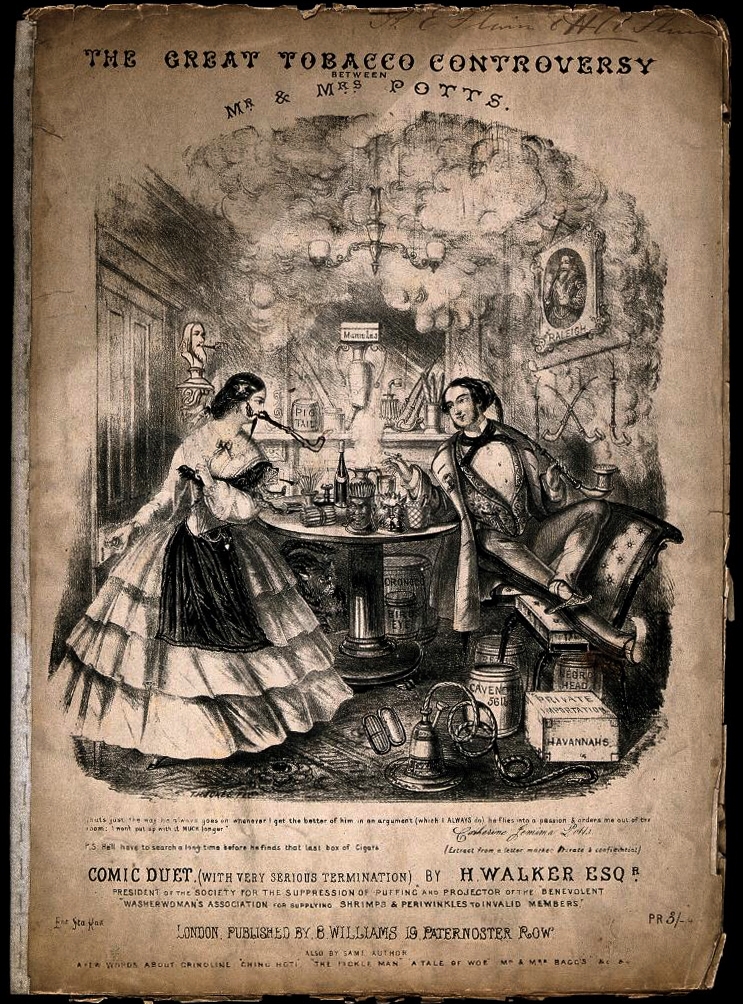

Hookah smoking was eventually replaced by the cheroot or cigar, both of which were more convenient and a much cheaper habit to maintain. Yet the custom of smoking hookahs died hard. By the 1820s ex-colonials retiring to Britain brought their hookahs with them, making the hookah a rather exotic presence in the British consciousness. In the dream world of ‘Alice in Wonderland’ (1865) the caterpillar smoked a hookah. The "great tobacco controversy" in the UK medical and popular press of 1857 was a debate about the effects of smoking tobacco on health. On this song sheet, Mrs Potts tells her husband that she is sure that smoking does him harm as he sits surrounded by all his smoking paraphernalia, including a hookah.

In the 21st century, hookah (or shisha) smoking is back in fashion, with shisha lounges and hookah bars in many countries (including India). Hookah smoking is sometimes seen as a ‘healthier’ way to smoke tobacco, but there is no evidence to support this. The same mix of tar, nicotine and other toxic chemicals is inhaled as in other kinds of smoking, as well as the toxic fumes from the charcoal used to burn the tobacco. Non-tobacco products have been developed as apparently healthier options for hookah smoking, though most are untested. But perhaps this is an indication that it is the ritual and social interaction as much as the tobacco that has people hooked on the hookah.

About the author

Baijayanti Chatterjee

Dr Baijayanti Chatterjee teaches history at Seth Anandram Jaipuria College in Kolkata, India. An Old Calcutta enthusiast, she obtained her doctoral degree from Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, for her research on 18th-century Bengal. Her work mainly focuses on the early British era, analysing the impact of the colonial transition on state, society and economy in 18th-century India.