Chloroform has been used by everyone from experimental surgeons to crime-fiction writers, and even a pregnant Queen Victoria. Journalist and murder-mystery fan David Jesudason explains how a one-time Edinburgh party drug went from operating theatre to henchman’s kit bag.

How chloroform shaped the murder mystery

Words by David Jesudason

- In pictures

In 1847 Edinburgh obstetrician Sir James Simpson was searching for a new inhalable anaesthetic for use during childbirth. Surgeons like Simpson needed a replacement for ether, which had proved impractical for long operations. During his search, Simpson and his assistants tested drug samples after dinner, including chloroform. According to the book ‘Simpson the Obstetrician’ by Myrtle Simpson, party guest Agnes Petrie, aged 16, was in ecstasy after trying it, shouting: “I’m an angel, oh, an angel.” Like scenes from Edinburgh-set film ‘Trainspotting’, guests at 52 Queen Street partied until their supplies ran out at three in the morning.

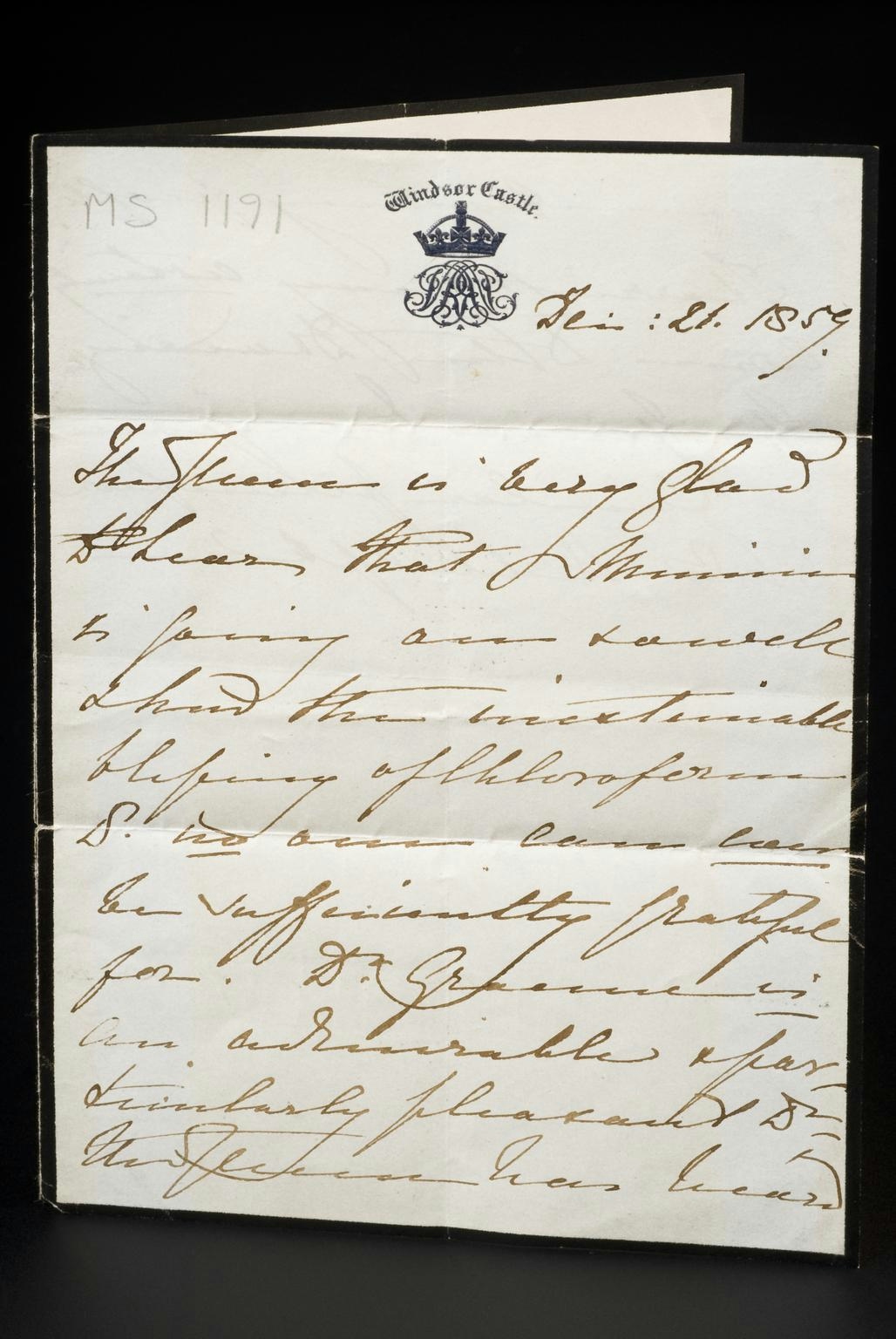

Today drug trials normally last between five and ten years. In 1847, Simpson administered chloroform for the first time during childbirth just seven days after his party on 8 November. He wrote that he placed his patient, Jane Carstairs, “under the influence of chloroform by moistening, with half a teaspoonful of the liquid, a pocket handkerchief rolled up into a funnel shape”. The baby, Wilhelmina (pictured when older), was delivered 25 minutes after the inhalation had begun, according to Morrice McCrae’s biography ‘Simpson: The Turbulent Life of a Medical Pioneer’. Two days later the drug was used four more times at Simpson’s Queen Street address to remove a tooth and for three surgical operations.

In the 19th century it was still widely believed that pain in childbirth was ‘God’s will’ and that the use of chloroform would slow labour down. Charles Dickens’s wife Catherine (who had ten children) and Queen Victoria (who had nine) helped to change this by showing other mothers chloroform could be a safe drug. Catherine’s eighth baby was delivered with the help of chloroform in 1849. Queen Victoria also used it during the birth of her eighth child, Leopold. It took 53 minutes for him to be delivered by physician John Snow in 1853. Ever the celebrity influencer, the monarch enthused about the drug: “Blessed chloroform, soothing, quieting and delightful beyond measure.”

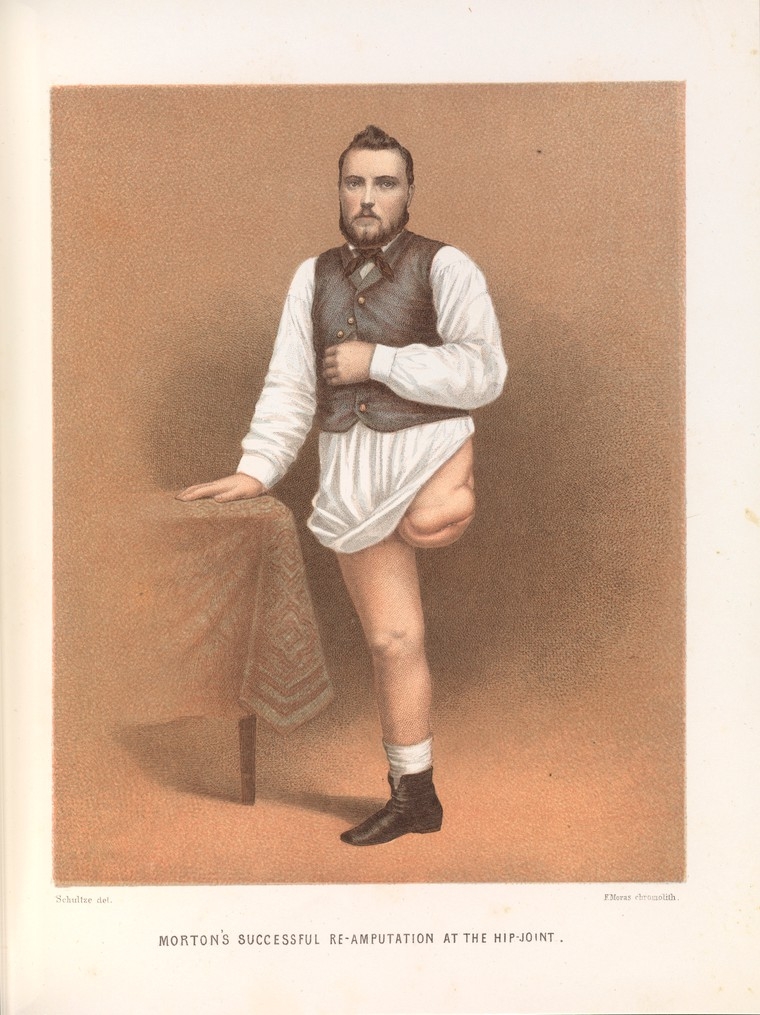

As well as for childbirth, doctors began to use chloroform for other operations. Some surgeons still preferred ether, though, especially for procedures involving the severely injured. It was the US Civil War (1861–5) that changed this. During the conflict it became common for field surgeons to anaesthetise the wounded, especially when amputations were needed. Its widespread use significantly improved survival rates, and Linda Stratman in ‘Chloroform’ wrote: “The argument about its suitability in military injuries was effectively over. Chloroform had gone to war – and it had won.”

The widespread use of chloroform inspired Victorian novelists, such as Wilkie Collins, who created nefarious characters who were now able to anaesthetise victims. His novel ‘The Moonstone’, published in 1868, is often cited as the first modern detective novel, as it adopts an English country-house setting, a skilled amateur sleuth and a hapless local police force. It also uses the drugging of gentleman detective Blake as its main plot twist. The narcotic trance Blake suffers was inspired by Collins’ own experiences: according to Andrew Lycett’s biography of the writer, Collins regularly took opioids

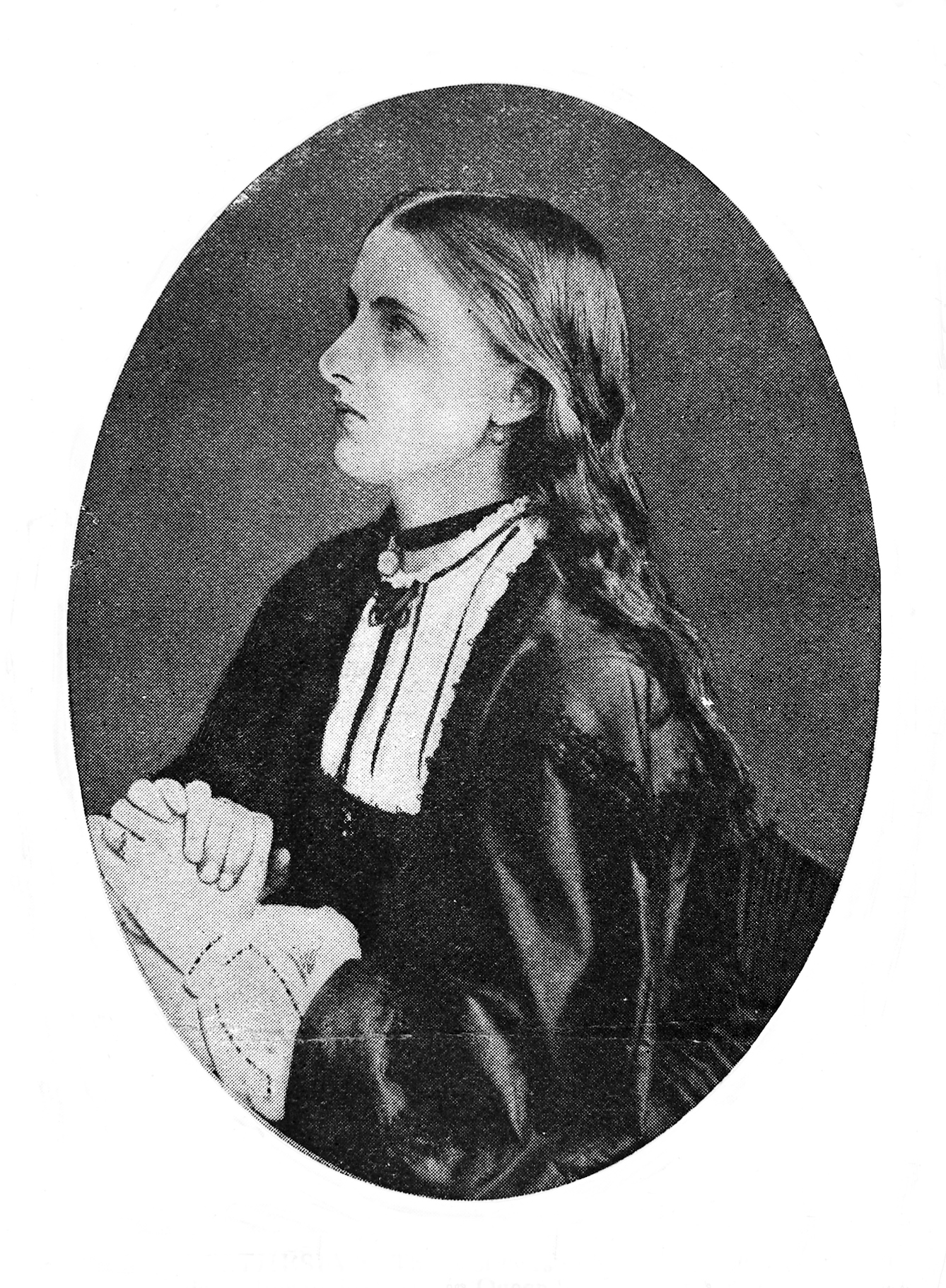

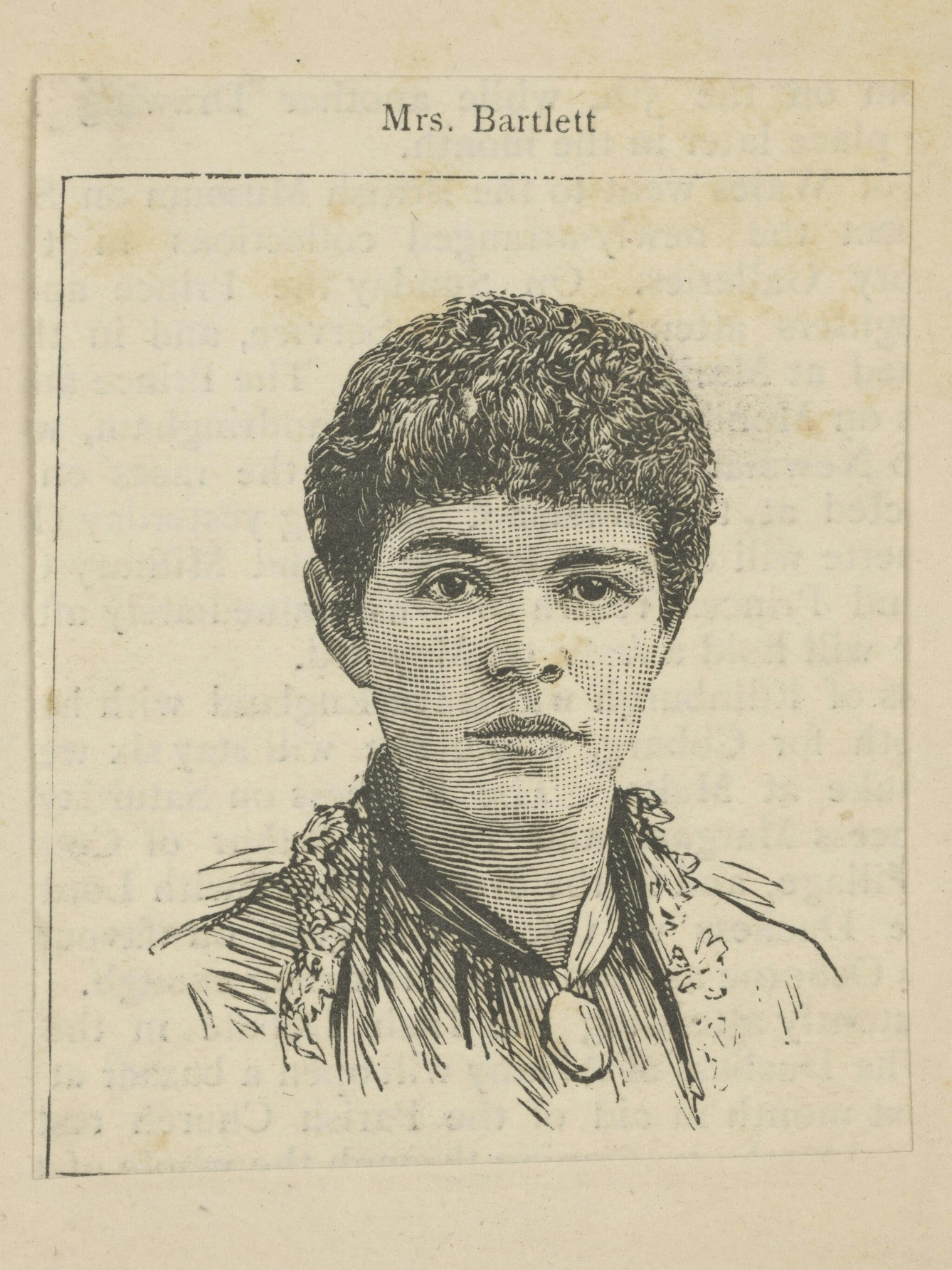

In 1886, a “chloroform murder” intrigued Victorians. Adelaide Bartlett (pictured) was accused of poisoning her grocer husband, Edwin, after he was found dead with traces of the drug in his stomach. The case could have been extracted from a novel like ‘The Moonstone’: the wealthy but ugly husband; the Methodist minister interested in hypnotism who is infatuated with the accused; an amended will. And, crucially, a missing bottle of chloroform, which was never found. Adelaide was acquitted but many observers still believed she was guilty. After the trial she changed her name and started a new life.

Bartlett’s trial and other criminal cases, such as that of the murderous doctor Henry Howard Holmes, ensured that chloroform gained headlines for all the wrong reasons. Widely dubbed “America’s first serial killer”, Holmes claimed to have killed 27, although some of his ‘victims’ turned up alive. The real figure was probably nine, but he did notoriously murder his business partner using chloroform to disable him. Alongside these salacious stories, chloroform was in the news for causing accidental deaths. A report in 1894 detailed ten deaths from the delayed effects of chloroform, and a series of early 20th-century investigations caused it to be abandoned by the medical profession and replaced by other anaesthesia.

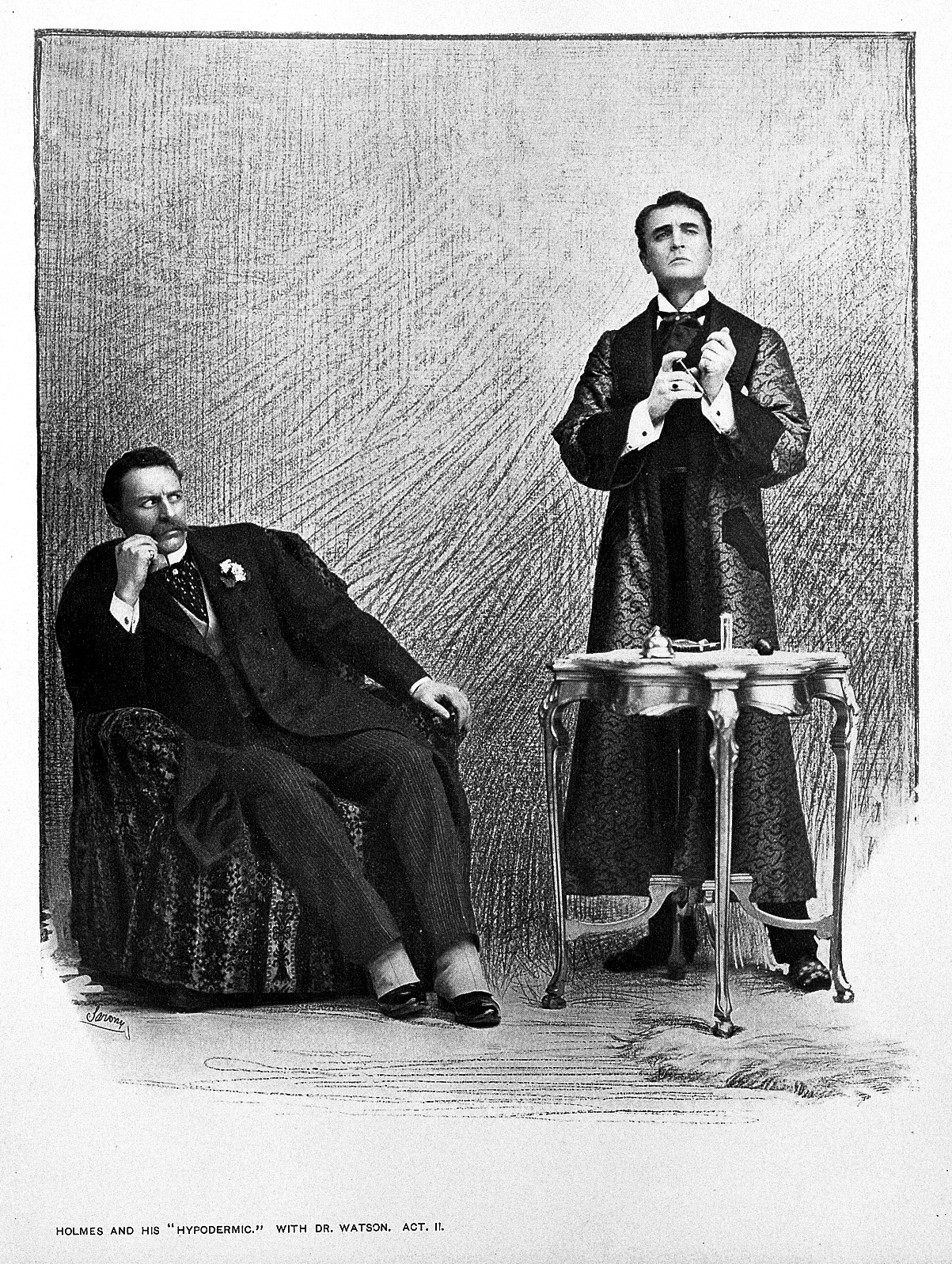

The notoriety of chloroform was adeptly harnessed by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. In several Sherlock Holmes stories, such as ‘His Last Bow’, chloroform is used in a way we would recognise today. In this story, Holmes himself incapacitates a spy by covering his victim’s mouth with a rag dipped in chloroform. The twist is that chloroform cannot be effectively administered in this way, as it would take longer than a few seconds to anaesthetise someone. Covering their mouth with it would probably suffocate them too. Surely Holmes would have deduced this? But, as Watson once said of Holmes, “His ignorance was as remarkable as his knowledge.”

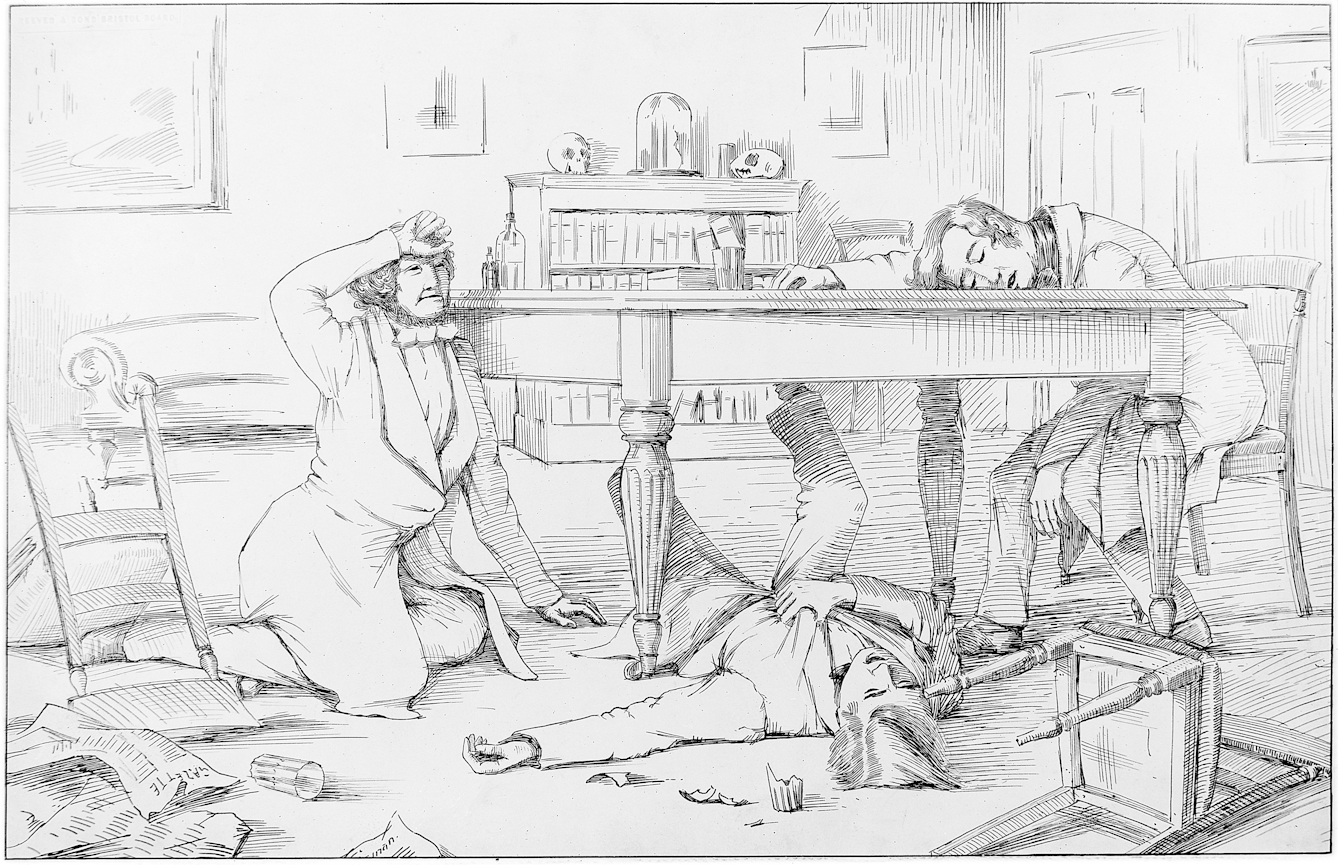

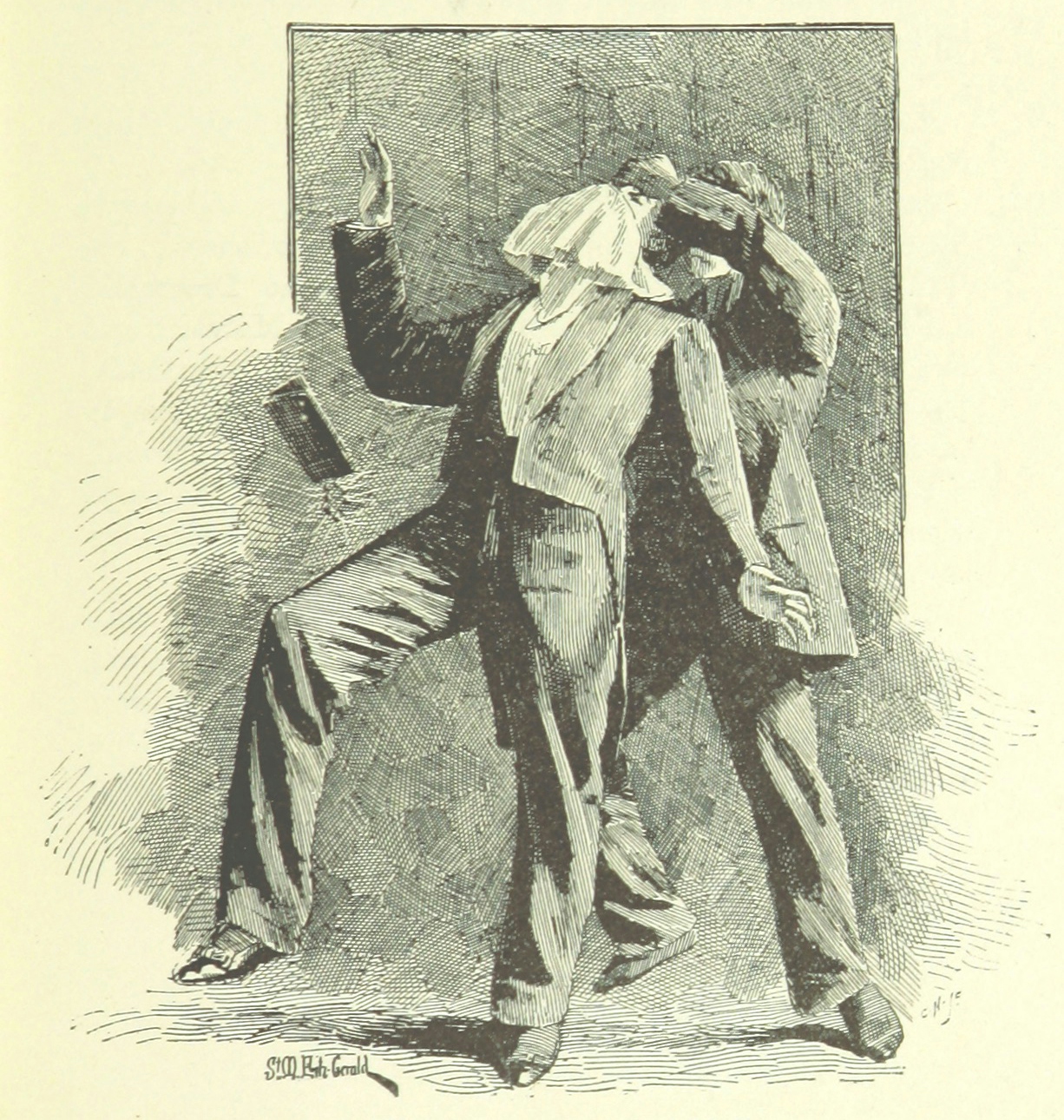

A lot of crime fiction employs implausible plot devices, like chloroform use, to keep audiences engaged. When administered to incapacitate a powerful protagonist (as shown here in Fergus Hume’s ‘The Dwarf’s Chamber’), it taps into a primal fear that anyone can be disarmed instantly. Modern procedural dramas continue to use things like the chloroformed rag, as they need these sudden moments of peril to keep us on edge. CBS’s ‘Elementary’, for example, loves to keep episodes taut by using such devices. My advice? Watch out for anyone aged under 60 who uses a handkerchief instead of Kleenex.

About the author

David Jesudason

David Jesudason is a freelance journalist who covers race issues for BBC Culture, Pellicle and Vittles. He was named Beer Writer of the Year in 2023, after his first book ‘Desi Pubs, A Guide to British-Indian Pubs, Food and Culture’ was hailed as “the most important volume on pubs in 50 years”. David also writes ‘Pub Episodes of My Life’, a weekly newsletter about the drinking establishments that serve marginalised people.