For Micha Frazer-Carroll, mental health conditions and disabilities are an undeniable part of her Caribbean family’s shared history – but many of her relatives choose not to see, name or diagnose their experiences this way. The Black diaspora has complex attitudes toward healthcare systems, which Micha traces back to the slave trade when disability and Blackness became heavily associated with one another.

How the slave trade’s medical legacies persist

Words by Micha Frazer-Carrollartwork by Joelle Avelinoaverage reading time 10 minutes

- Article

My large Caribbean family stretches across the United Kingdom, United States and Antigua. Threaded into our shared history are what you or I might call “mental health conditions” and “disabilities” but not everyone chooses to see or name these experiences this way.

There are historical reasons for this. Reasons tied to the enslavement of our ancestors.

Racism is disabling

Many relatives have been through what people today would commonly refer to as “depression”, “anxiety” and “racial trauma”. Yet we would never have thought to describe them as such when I was growing up in the 1990s and 2000s. During this era, my family were sceptical of engaging with the mental health system. In the instances where doctors did suggest mental health diagnoses, those suggestions would be rejected.

Members of my family have experienced mental distress. The ways it has manifested are hard to pin down and explicitly name, despite undoubtedly being present. Others were physically disabled, chronically ill or lived with high support needs.

Recently I had a conversation with my sister; she was telling me about her trip to the doctor. During her appointment, she was asked if there was any history of mental illness in the family. Her response was something to the effect of: “Of course, virtually everyone – isn’t that the case for most families?”

“Relatives have been through what people today would commonly refer to as ‘depression’, ‘anxiety’ and ‘racial trauma’.”

But the social and systemic discrimination Black people face means we are disproportionately more likely to experience disability and mental health conditions.

The current global system of racial capitalism causes and exacerbates disabilities and mental health conditions. Disability is not just a result of individual health conditions, but is caused and created by factors relating to race and class.

A system that provokes scepticism

In my work on race and disability, it’s always felt important to emphasise the disabling impacts of our racist society. Those systemic biases show up within our healthcare systems, and as a result my relatives have faced a lot of medical mistreatment.

An experience that sticks out is learning about the treatment of my elders in the UK in the 1970s: they were devout Pentecostal Christians and they would speak in “tongues”, saying they could hear the voice of God. Because of this, they were non-consensually diagnosed with psychosis by medical professionals.

It’s no wonder to me that my mother then became cautious about engaging with medical systems – the people she loved were misunderstood, medicalised and pathologised by professionals.

When we say someone is pathologised, it means their behaviour or feelings are treated as if they are a disease or disorder. Pathologisation might be helpful or harmful; I engaged with the UK medical system to get a diagnosis and have used the language of diagnosis to receive treatment and support.

I find my diagnosis helpful because it allows me to request reasonable adjustments from an employer. Diagnosis has also helped me find communities of people who share similar life experiences. Yet while some of my relatives today have chosen to go for a formal diagnosis for mental health conditions or a disability, the majority have not.

I wrote a book on mental health called ‘Mad World’. The hours of research that went into it have convinced me that these attitudes and behaviours are influenced by race and legacies of enslavement.

The harsh conditions of slavery

During the enslavement period, Blackness and disability became heavily associated with one another.

The gruelling reality of slave labour took a toll on people’s bodies. On plantations in the Caribbean and the Antebellum South of the United States, disability was a predictable outcome of the living conditions Black people faced.

The various ways in which enslaved people could become disabled were virtually endless. Brutal punishments such as branding, whipping or having teeth knocked out were common.

The formerly enslaved abolitionist Ottobah Cugoano wrote that on a plantation in Grenada, he saw: “The most dreadful scenes of misery and cruelty… miserable companions often cruelly lashed, and, as it were, cut to pieces, for the most trifling faults.”

Enslaved people lost limbs, fingers and toes from brutal working conditions. They developed chronic illnesses and diseases because of the system, and experienced infections that damaged their organs.

Women were prone to fertility problems and miscarriage – often due to physical abuse. Unsurprisingly, mental distress was also common.

Stereotyped as defective

Enslaved people’s experiences of disability were a subject of debate among pro- and anti-slavery thinkers and campaigners, who were mostly white or light-skinned, which further stigmatised and oppressed Black people.

Anti-slavery campaigners used disability as an argument for abolition. They emphasised enslavement as a disabling process, but, by extension, portrayed enslaved populations as being inevitably disabled. This helped solidify conceptions of Black bodies as inherently inferior.

This legacy might naturally produce a complex relationship to the topic in Black communities today: if virtually all of us have been disabled by racialised violence, then disability becomes a fact of life rather than a distinct identity-marker.

In other words: if all of us are disabled, then perhaps none of us are – or, at least, it might seem unnecessary for us to name it.

“The gruelling reality of slave labour took a toll on people’s bodies.”

In the Antebellum South of the United States and the colonial Caribbean, proponents of slavery suggested that Black people were a “defective” and “monstrous” race that was well suited to the brutal conditions of slave labour. English colonial leaders viewed Black people as being intellectually disabled but having ideal bodies to work the fields and participate in forced breeding.

We were simultaneously seen as defective and somewhat superhuman – an inferior race that could withstand conditions that white people could not.

Pro-slavery writers also argued that there were higher incidences of blindness, deafness and intellectual disability in freedmen (those who had been released from slavery by legal means). This was to further support the idea that Black people’s bodies were inherently different to non-Black bodies.

Here we can see a clear paradox in how Black people were framed in relation to disability: we were simultaneously seen as defective and somewhat superhuman – an inferior race that could withstand conditions that white people could not.

This logic continued following abolition: Black people were framed throughout the eugenics movement as strong, primitive, and at a greater likelihood of developing mental illness due to having biologically inferior brains.

And it continues today. Black people are stereotyped as violent and criminal but simultaneously seen as possessing superhuman strength and ability. It’s something I often come up against in my work as a journalist – police killings and doctors’ reluctance to give Black people adequate pain medication are just two clear examples of this.

Healthcare’s role in sustaining slavery

Proponents of slavery were also interested in managing the health of enslaved people, insofar as it impacted their ability to work.

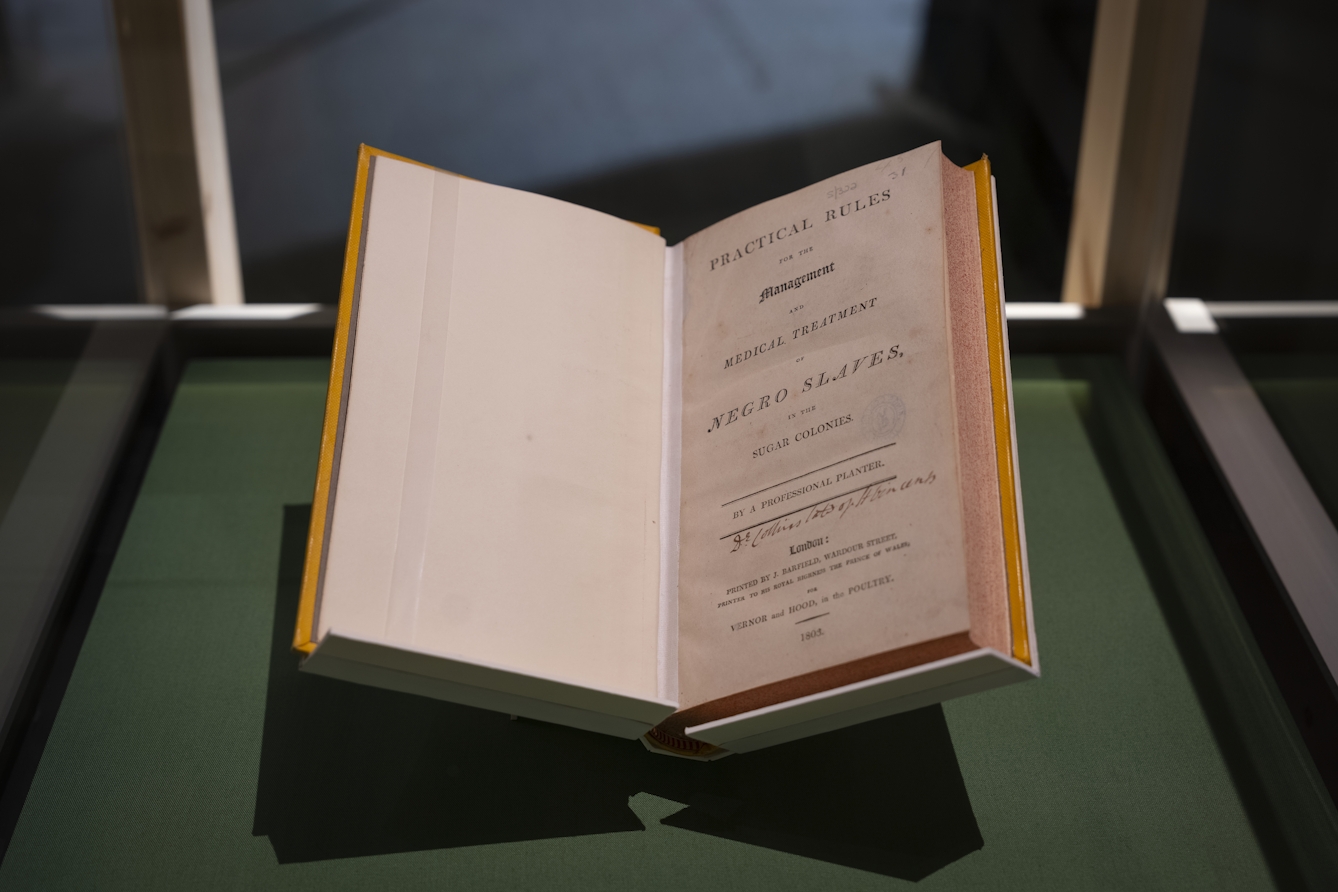

On a visit to Wellcome Collection’s ‘Hard Graft’ exhibition in 2024, I saw the pages of a book published in 1803 called ‘Practical Rules For the Management and Medical Treatment of Negro Slaves, in the Sugar Colonies’. In it, Dr David Collins argues that the health of enslaved people was a valuable investment. As you can see(view in catalogue), it includes treatments for infectious diseases ranging from "yaws" (a chronic skin infection) to “pox”, and shows us that Western medicine played a crucial role in sustaining the economy of slavery.

Though we know the harsh conditions of slavery inevitably led to poor health and disability, some slave owners would instruct physicians to detect malingering to ensure that enslaved people did not use illness and disability as a means of avoiding labour.

Of course, there were other methods for managing the “problem” of poor health and disability on the plantation too. There is evidence that in other contexts, disabled enslaved people would not receive treatment but would rather be banished and forced to fend for themselves – or executed. These approaches again would have been informed by economic motives rather than moral or humane ones. Other disabled slaves might be sold and told to conceal their impairments from prospective buyers.

How rebellion is pathologised

Enslaved people were pathologised for rebellion against white supremacy. In 1851, the American physician Samuel A Cartwright proposed the diagnosis of “drapetomania”(view in catalogue) to be given to Black people who fled from plantations. It was a supposed mental illness invented by Cartwright, who said it made enslaved people want to run away. His suggested cure was whipping.

Another of Cartwright’s suggested diagnoses was “dysaesthesia aethiopica”, a mental illness that supposedly caused disobedience, disrespect and a refusal of work in enslaved communities. While Cartwright’s ideas were not universally accepted, he was widely respected in the US and received an award from Harvard University’s medical committee.

Following abolition, these forms of political pathologisation led to the creation of “lunatic asylums”, which mirrored slavery’s system of involuntary incarceration.

Black people in asylums in the 19th century American South were frequently diagnosed with “political excitement”, and Rastafarian activists and other colonial dissidents were routinely detained at Jamaica’s Bellevue asylum.

Black people’s cultures and behaviours remain at risk of pathologisation – treated as if they’re illnesses in need of cure.

During this era, the logics of the plantation often permeated the treatment of Black people in asylums, with asylum superintendents such as Daniel Burr Conrad in Virginia suggesting that manual labour was the “chief” cure for Black asylum residents. Into the 20th century, Black detainees were put to work in agricultural fields in the South, while Black civil rights activists were often admitted to institutions for what was described by some psychiatrists as a “protest psychosis”.

“Uncovering these historical links between enslavement and disability have helped me understand my family’s complex interaction with the subject.”

Today, Black people’s cultures and behaviours remain at risk of pathologisation – treated as if they’re illnesses in need of cure. In my own life, this has made me think critically and more flexibly about beliefs in my own community that might be considered “unusual”, and careful to avoid stigmatising or pathologising anyone who thinks differently to me.

A unique relationship to disability

Uncovering these historical links between enslavement and disability have helped me understand my family’s complex interaction with the subject in the present day, and why we might see or name our experiences differently.

In her book ‘Black Disability Politics’, academic and activist Sami Schalk speaks to numerous disabled Black Americans who articulate a similar ambivalence and complexity in their relationships to disability. Some emphasise that concepts of disablement and diagnosis have routinely been forced on Black populations for the purposes of subjugation and control.

I chime most with the sentiments of one interviewee, the activist T L Lewis, who argues that Black people need to be given agency over how they identify and engage with the terminology of disability.

For a long time, the Black Caribbean diaspora has had a unique relationship to disability, with Black people being positioned within, beside and beyond the category.

We have also been deprived of agency in our relationship to disability, with both disablement and “cure” being dictated by economic forces beyond our control. Because of this, I staunchly support people’s right to reject medicalisation, particularly those who have always been more likely to be pathologised.

About the contributors

Micha Frazer-Carroll

Micha is a freelance journalist and author of ‘Mad World: The Politics of Mental Health’. She has worked for publications including the Guardian, gal-dem and the Independent. She has also done communications work for anti-racist, abolitionist and disability justice organisations including BLMUK, Healing Justice London and NEUROMANCERS, a peer support initiative for neurodivergent people.

Joelle Avelino

Joelle Avelino is a Congolese and Angolan illustrator who grew up in the United Kingdom. She is particularly motivated by the need for people from all races and backgrounds to see themselves in the world around them.