How we perceive the world through our senses is often seen as what makes us human. But questioning the assumptions we make regarding our senses can help us think differently about our relationship with the animal world. Rather than separating us, our senses can show how animals and humans are interconnected.

Humans, animals and the sensory world

Words by Wanda D’Onofrio

- In pictures

In terms of evolution, the senses have been a survival kit for animals and humans alike. Many species share fundamental behaviours, prompted by experiences such as the pleasure of taste. The ‘Hortus Sanitatis’ (“The Garden of Health’), compiled by Jacob Meydenbach and dated 1491, shows the practical uses of animals in curing human diseases while showing through its images our common instincts.

Though humans and animals share many needs and senses, these have often been used to emphasise what makes us different. In this medieval representation of Aristotle's Theory of Perception, the perception of the world is mediated by the soul, which differs between humans and animals.

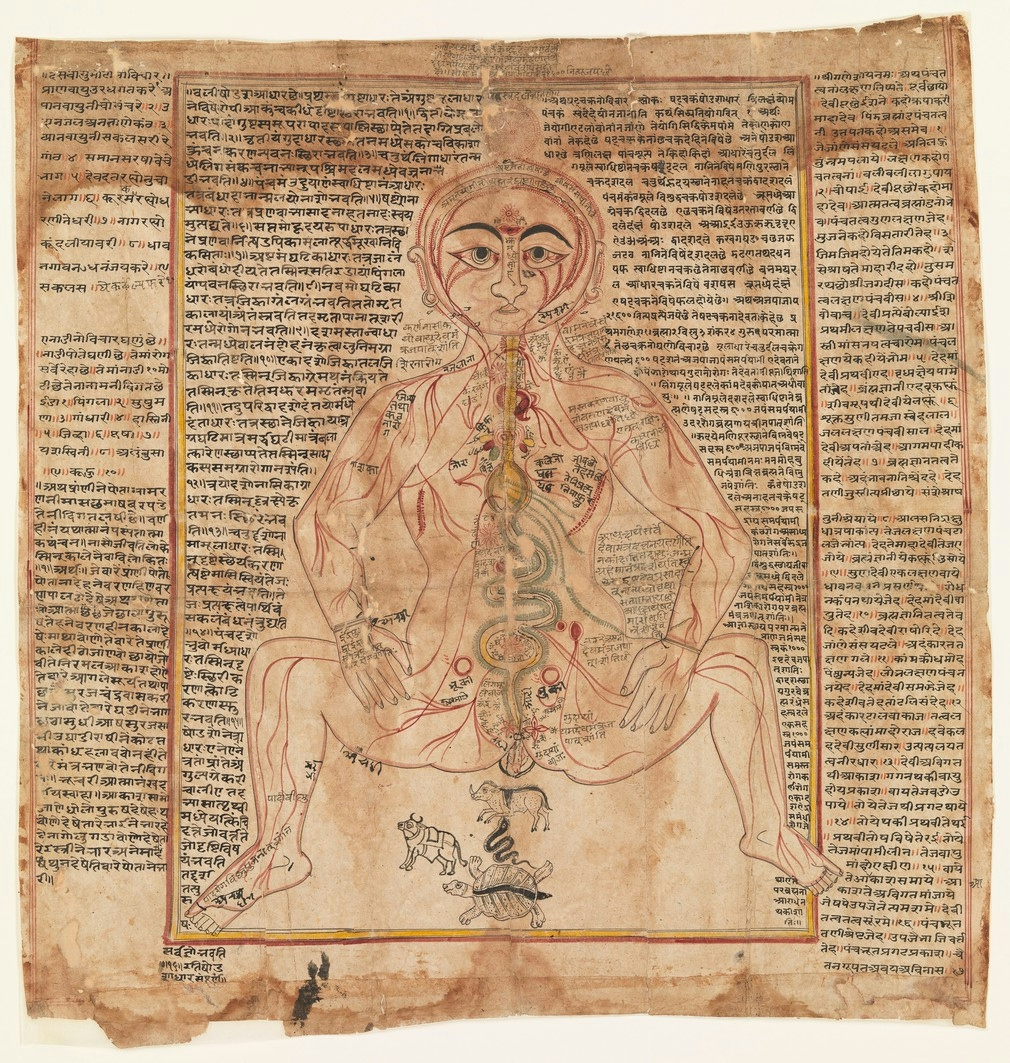

This image from western India combines medical and tantric approaches to the body. It shows anatomically accurate organs, chakras along the spinal column, and mythical and astrological animals below it. In this medical practice, humans, animals, and plants are all connected. The five chakras are represented by the lotus flower, and each of them is associated with both a physical organ and a sensory organ.

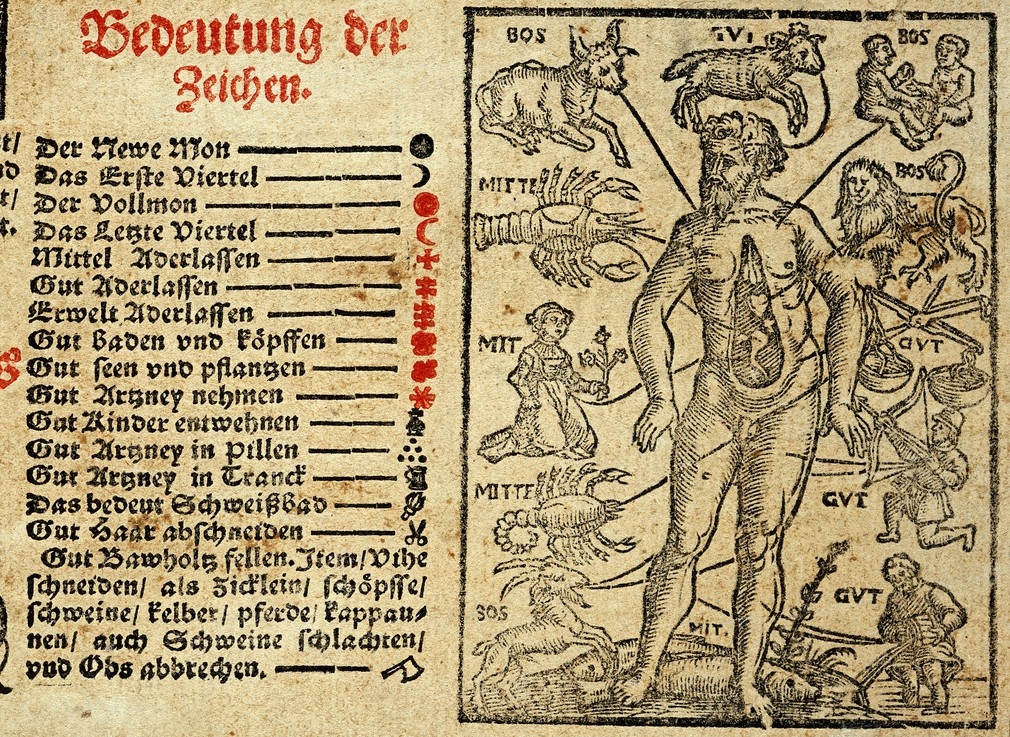

In medieval times there was a revival of ancient Greek medicine combined with Arabic astrology, which linked the functioning of the human body to the movements of the stars. This diagram of the 'Zodiac Man' explains how the astrological formations, or star signs, influence specific parts of the body. The educational use of allegorical animal figures emphasises the profound connection between species; humans could better understand themselves by comparing themselves with the animal world.

This allegorical image is part of a set of five engravings linking the senses to ancient Greek and Roman architecture. The sense of taste is represented by the Corinthian order, an ornate architectural style. On the right, a human figure and a monkey are both holding fruit. The pleasures of taste are emphasised by the animal and human behaviours, the abundance of fruit, and the complexity of the architecture.

In Louis-Léopold Boilly's illustration of the five senses (c. 1823), animal behaviours are used to illustrate human features and faults. The senses are often associated with morality, a combination used to encourage people to overcome animal desires. Since antiquity, animal behaviours have had symbolic meanings, not always positively linked to human qualities!

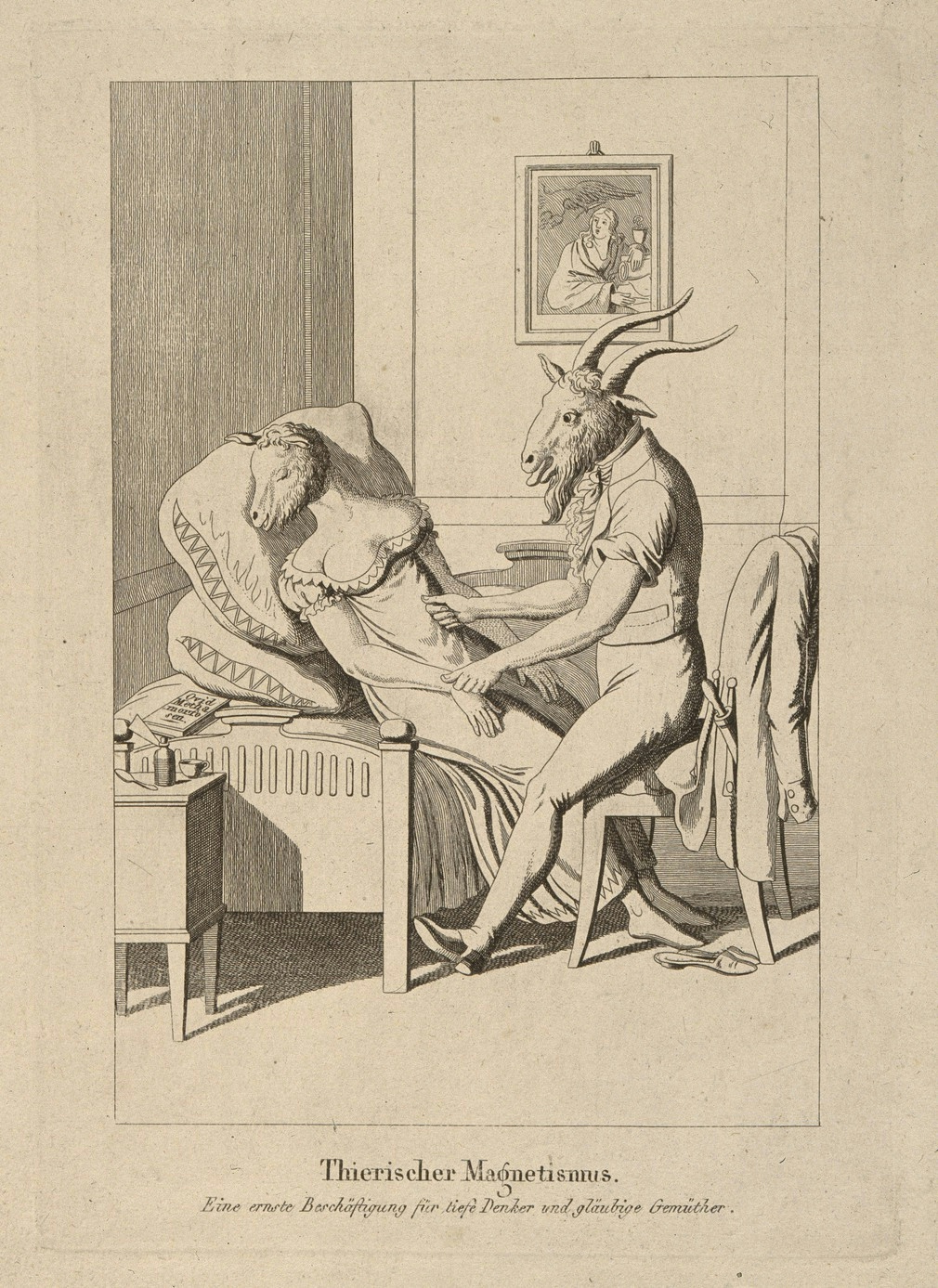

In the 18th century, physician Franz Mesmer started his healing practice, which he called 'animal magnetism'. Mesmer believed in an invisible natural force flowing through the universe and all living creatures. 'Animal magnetism' evokes the spontaneous capacity of animals to connect with their surroundings. Mesmer's research was controversial and inspired satirical pictures, such as this one, in which the figures are both goat-headed.

In this 17th-century engraving by Flemish artist Nicolaes de Bruyn, a woman plays music to a stag while God condemns Adam and Eve to exile. This representation of hearing belongs to a series of five engravings, each connecting one of the senses to an animal. Here the stag’s ability to avoid capture links it to the sense of hearing. This idyllic image shows two different aspects of animal and human relationships where, alongside the natural coexistence of species, social values are attributed to animals.

About the author

Wanda D’Onofrio

Wanda D’Onofrio is a postgraduate student of the Victoria & Albert Museum/Royal College of Art MA in History of Design. With a background in the history and restoration of textiles and costumes, she has worked internationally as a designer on a range of projects, including Iford Arts operatic season in 2018. Currently, her research interests include biotechnologies and genetics in the humanities and promoting the accessibility of science through its material culture.