Today most of us know what an unborn baby looks like. But for centuries the developing foetus was invisible: its appearance, behaviour and source of nourishment could only be guessed at. However, medical developments from the 18th century onwards allowed detail and accuracy to gradually inform our impressions of our earliest beginnings.

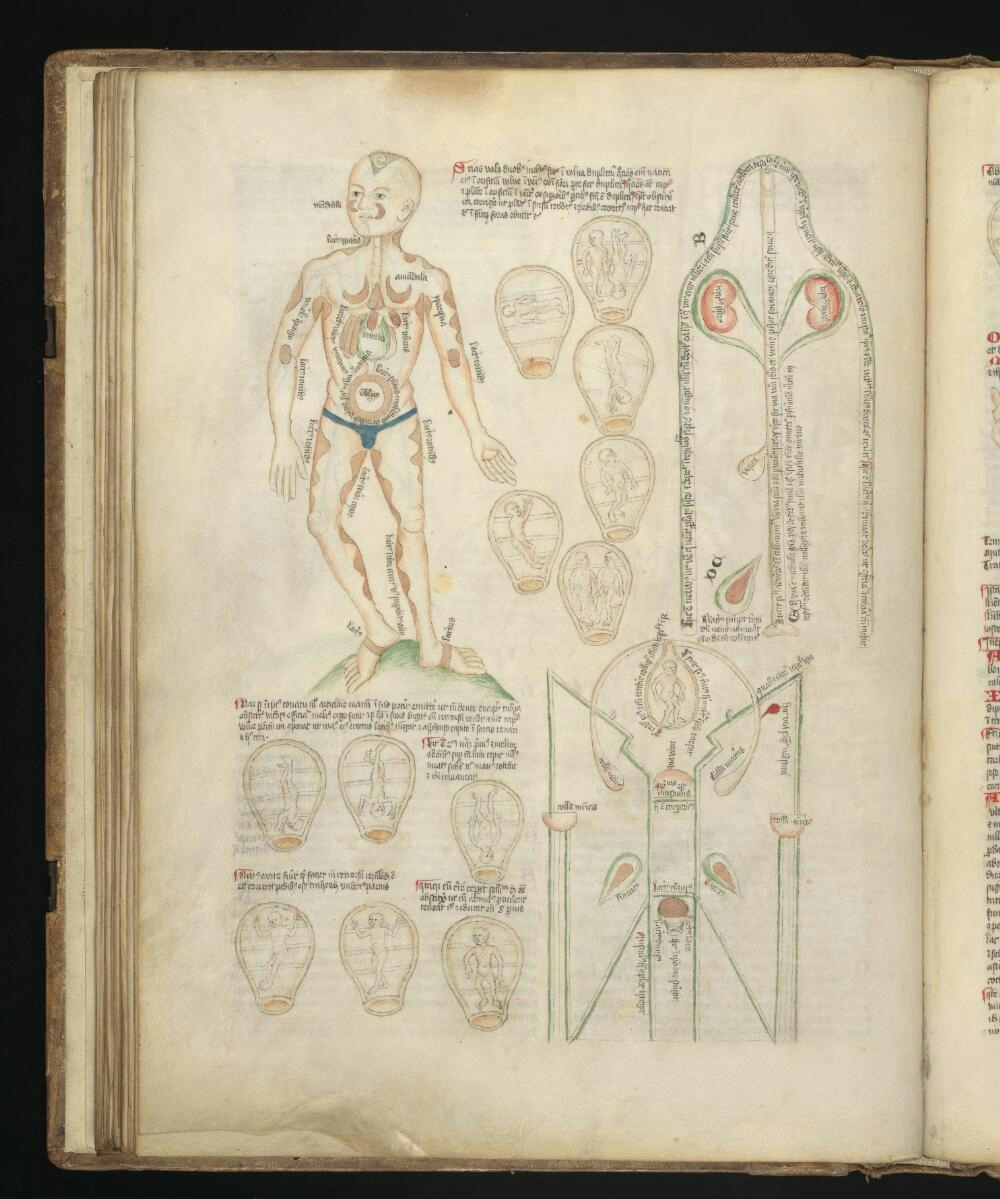

To modern eyes, historical pictures of the foetus can appear almost comical: the foetus does not look the way we know unborn babies look. Instead it has the features and proportions of an adult. Before ultrasound, scans, X-rays and dissection, the foetus in the womb was a hidden and mysterious being. During later pregnancy its rough shape and position could be felt, but what it looked like and how it behaved was unknown.

![Chart showing locations on the Large Intestine channel of arm yangming where acupuncture is prohibited during the eighth month of pregnancy, from Ishinpo [Chinese: Yi xin fang] (Remedies at the Heart of Medicine), by the Japanese author Yasuyori Tanba.](https://images.prismic.io/wellcomecollection/d9e48281-0a11-481b-957f-354ef96dbd8b_ImaginingTheFoetus2.jpg?w=1338&auto=compress%2Cformat&rect=&q=100)

People had many reasons for wanting to know what might be happening inside the womb. In this case, the image warns acupuncture practitioners in 10th-century China about where to avoid on pregnant patients, because of concerns that stimulating a particular area of the arm – the large intestine channel – might lead to miscarriage. Depicting the foetus served as a visual reminder of the pregnancy and the precautions it might require.

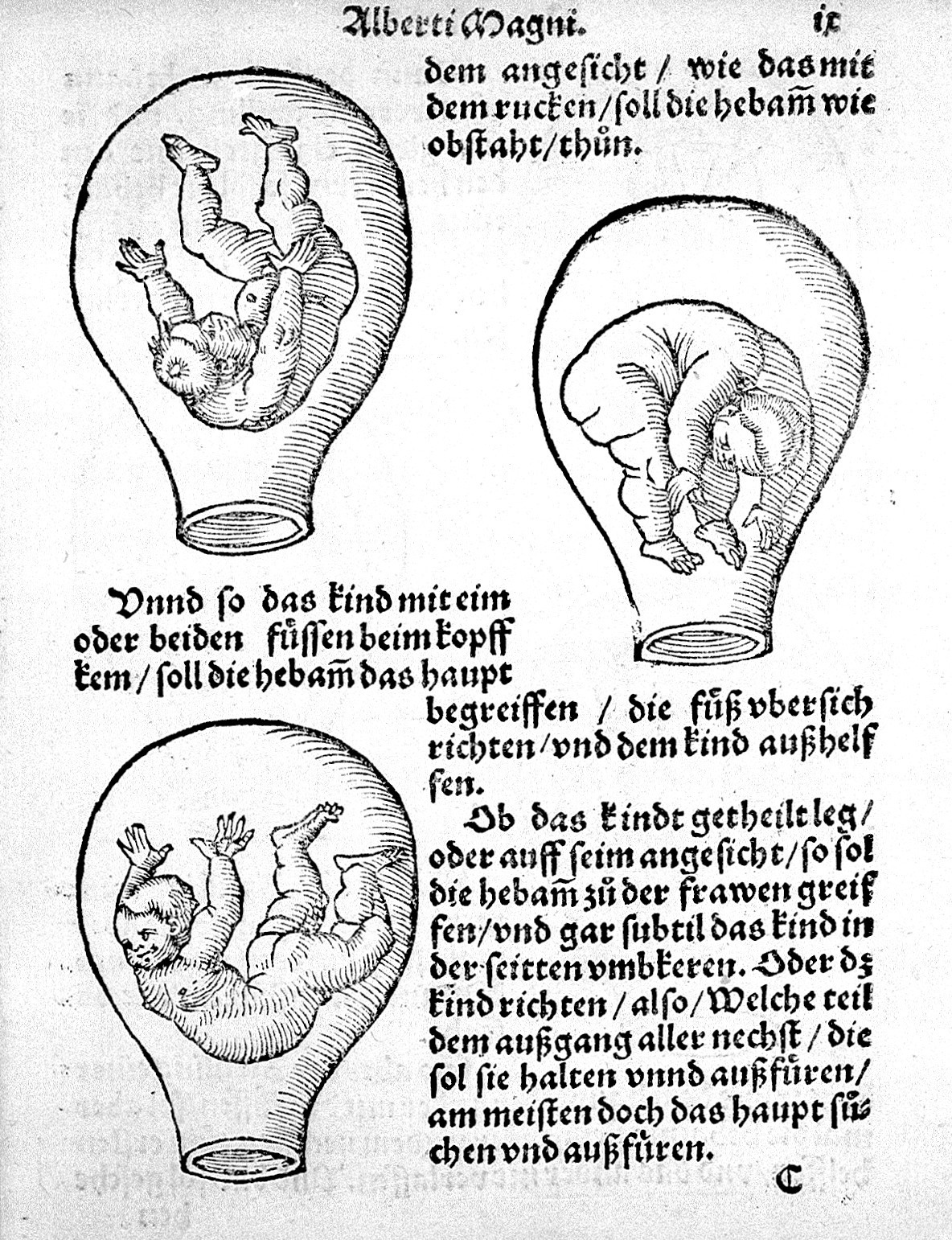

These pictures show the foetus utterly in its own world, free-floating in the uterus. The woman is not pictured, suggesting her uterus is just a vessel for the foetus. The sense of freedom and space for the foetus shown is probably based on women’s descriptions of foetal movement. By the 16th century, ‘textbooks’ about pregnancy and birth were appearing across Europe, as woodcut-printing technology meant images could be easily reproduced. Near-identical pictures of the foetus appear in books across several centuries and countries.

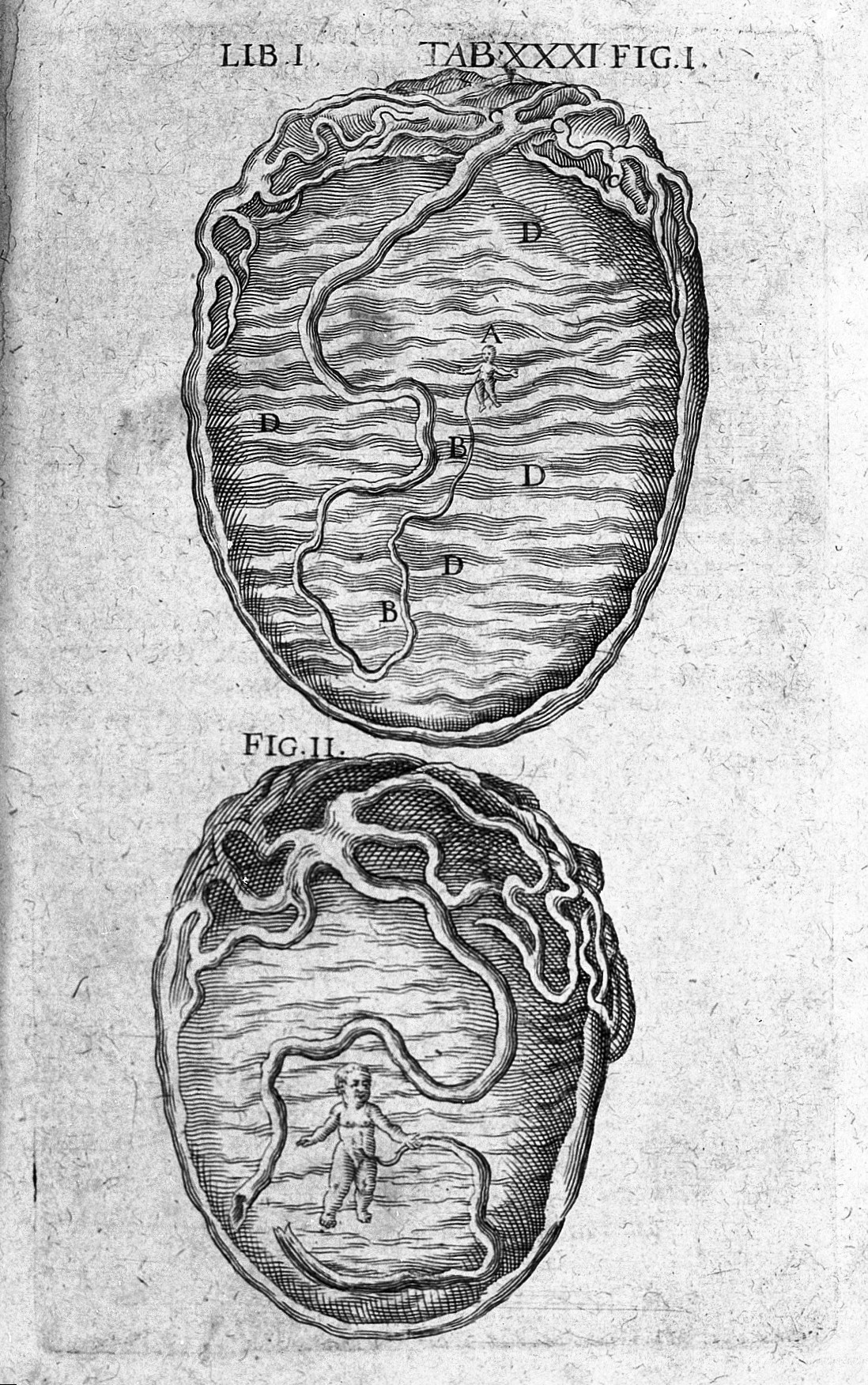

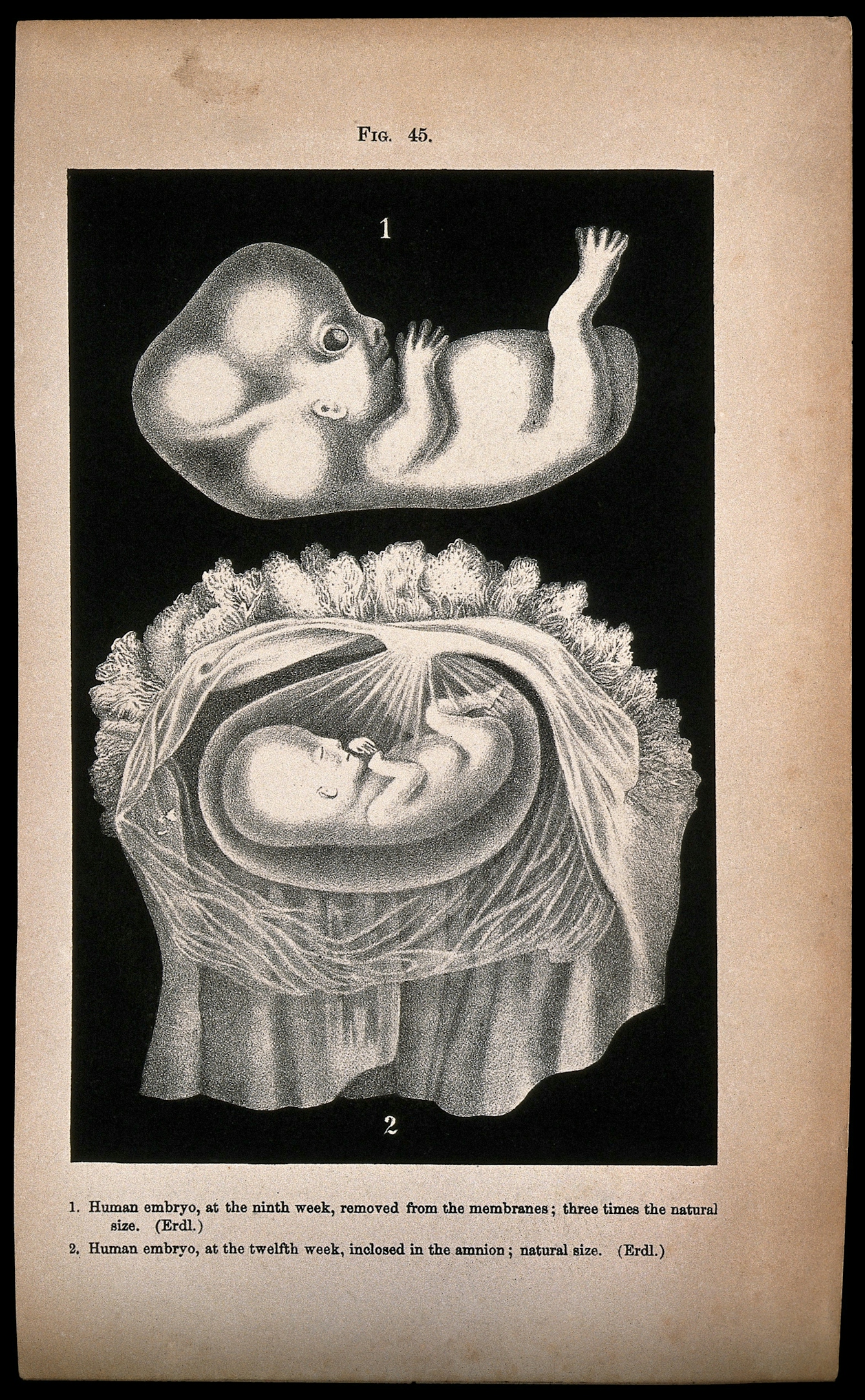

Birth doesn’t just the deliver the baby, but other contents of the uterus too, including the placenta, umbilical cord and amniotic fluid. Earlier drawings and woodcuts showed the foetus alone in the uterus; it was not until the 18th century, with the growing use of dissection, that these hidden elements of pregnancy could be explored in detail. This image from 1778 demonstrates that the foetus is nourished by a blood supply. The foetus is still seen as a very small being in its own world, partly because the image represents early pregnancy: the uterus was thought to be a static vessel, rather than an organ that would grow with the foetus.

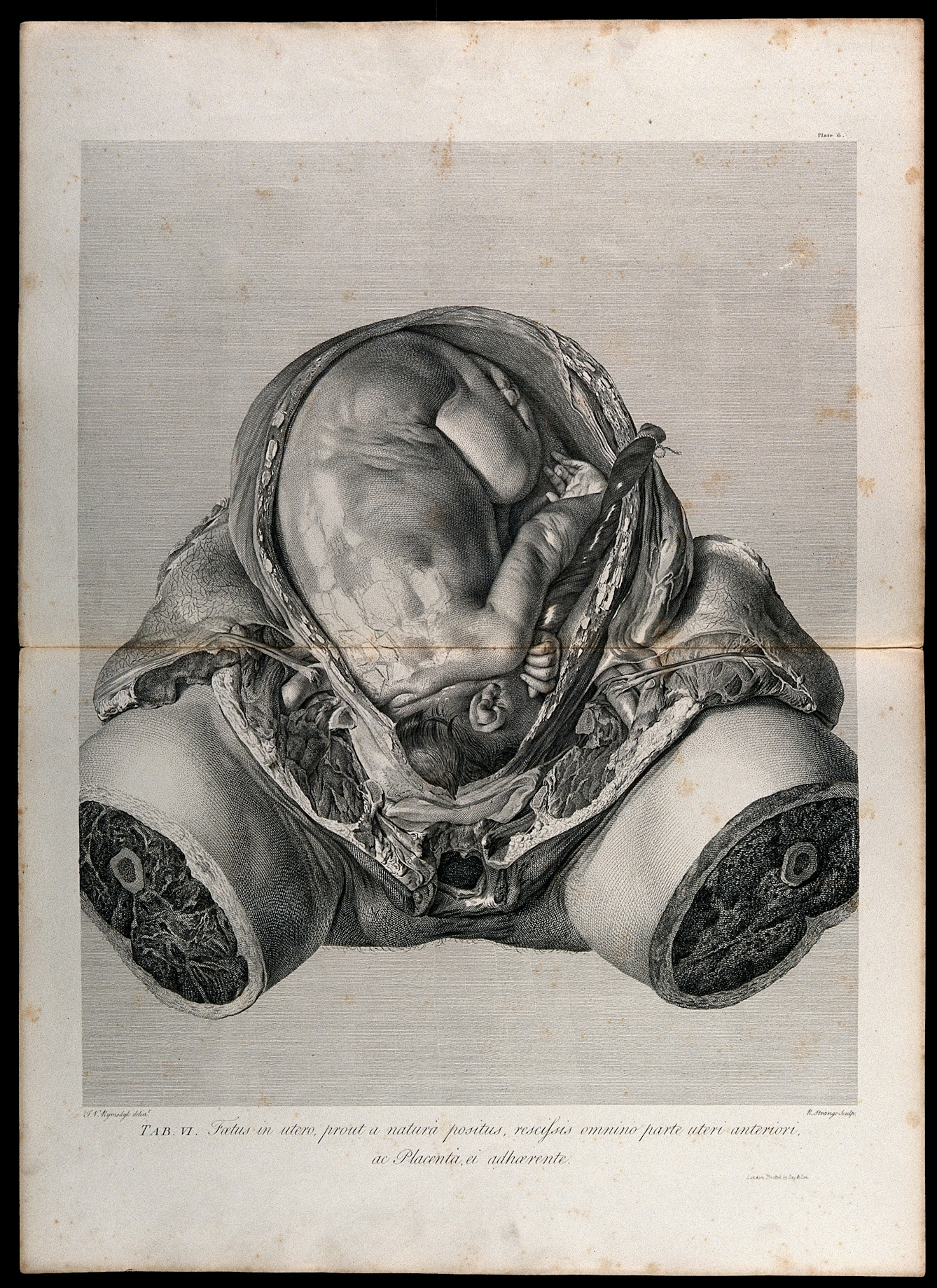

Pregnancy and birth could be risky times for women. The bodies of women who died in pregnancy or during childbirth became subjects of study during the 18th century, when dissection was becoming a more accepted form of discovery. The dissection of women’s bodies at various stages of pregnancy enabled the foetus to be tracked from the earliest stages. This image of a nine-month-old foetus contrasts with the earlier images of free-floating figures and shows the cramped conditions in which it lived. It also places the foetus and uterus in the body of the woman.

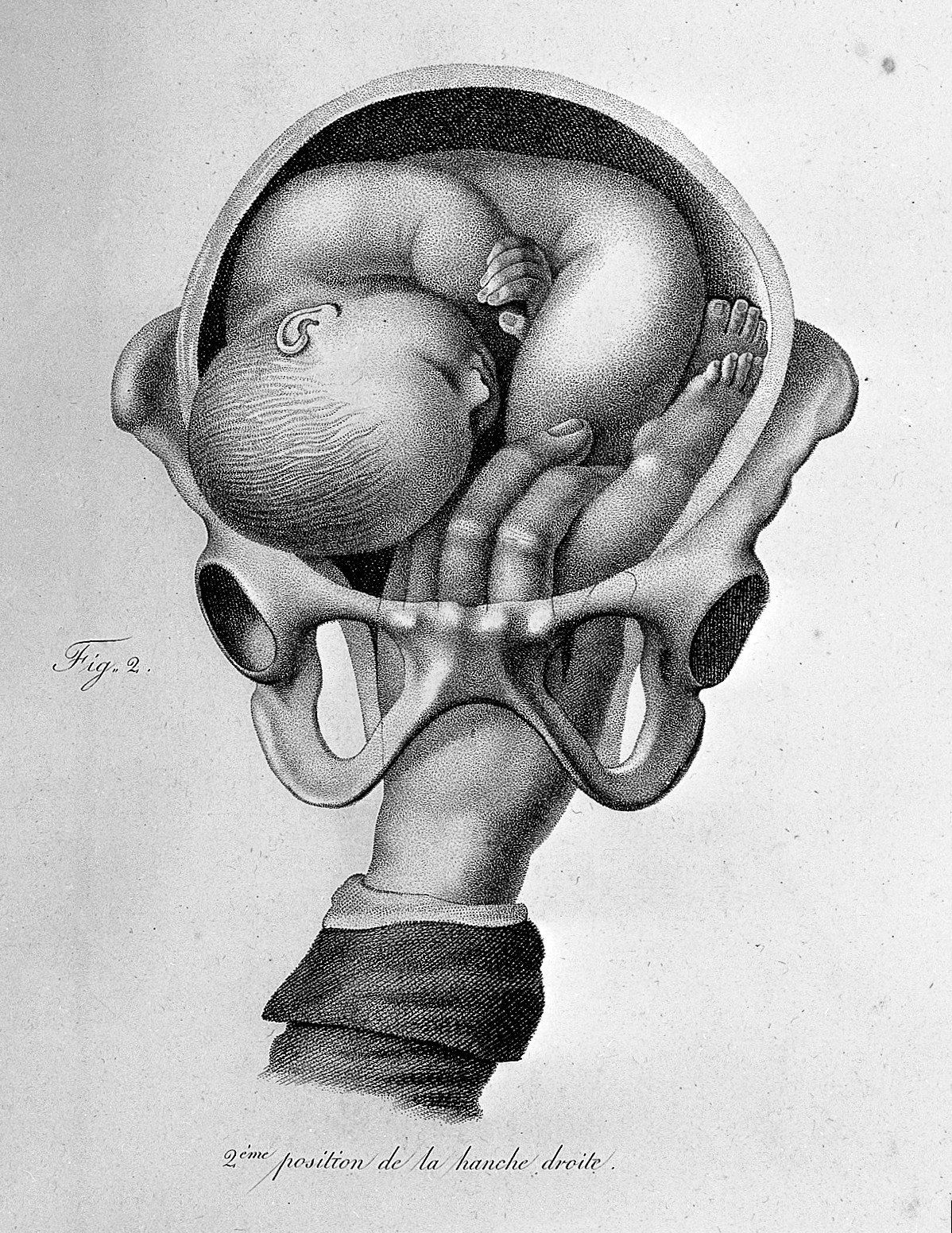

For most of history, pregnancy and birth have been “women’s work”. The mysteries of pregnancy were the exclusive province of women, through their connection with their own bodies and those of the women they cared for during labour. By the early 19th century the involvement of men (initially called man-midwives) in childbirth became more commonplace. Imagery of the foetus inside the uterus helped devise and teach different techniques for delivering babies. This French engraving shows the caregiver grasping the knee of a foetus to pull it down so it can be delivered feet first.

Images of the unborn foetus were not only used for teaching or scientific discussion: the foetus became visible in a range of ways – including this classically inspired relief from the early 19th century. It is a curious mixture of anatomy and romantic imagery. The partially dissected breasts and uterus contrast with the classical hairstyle and flowing drapes. The public were used to seeing naked bodies from the Greek and Roman periods, so putting a modern view of pregnancy in classical garb may have made it more acceptable than the sight of a contemporary pregnant body.

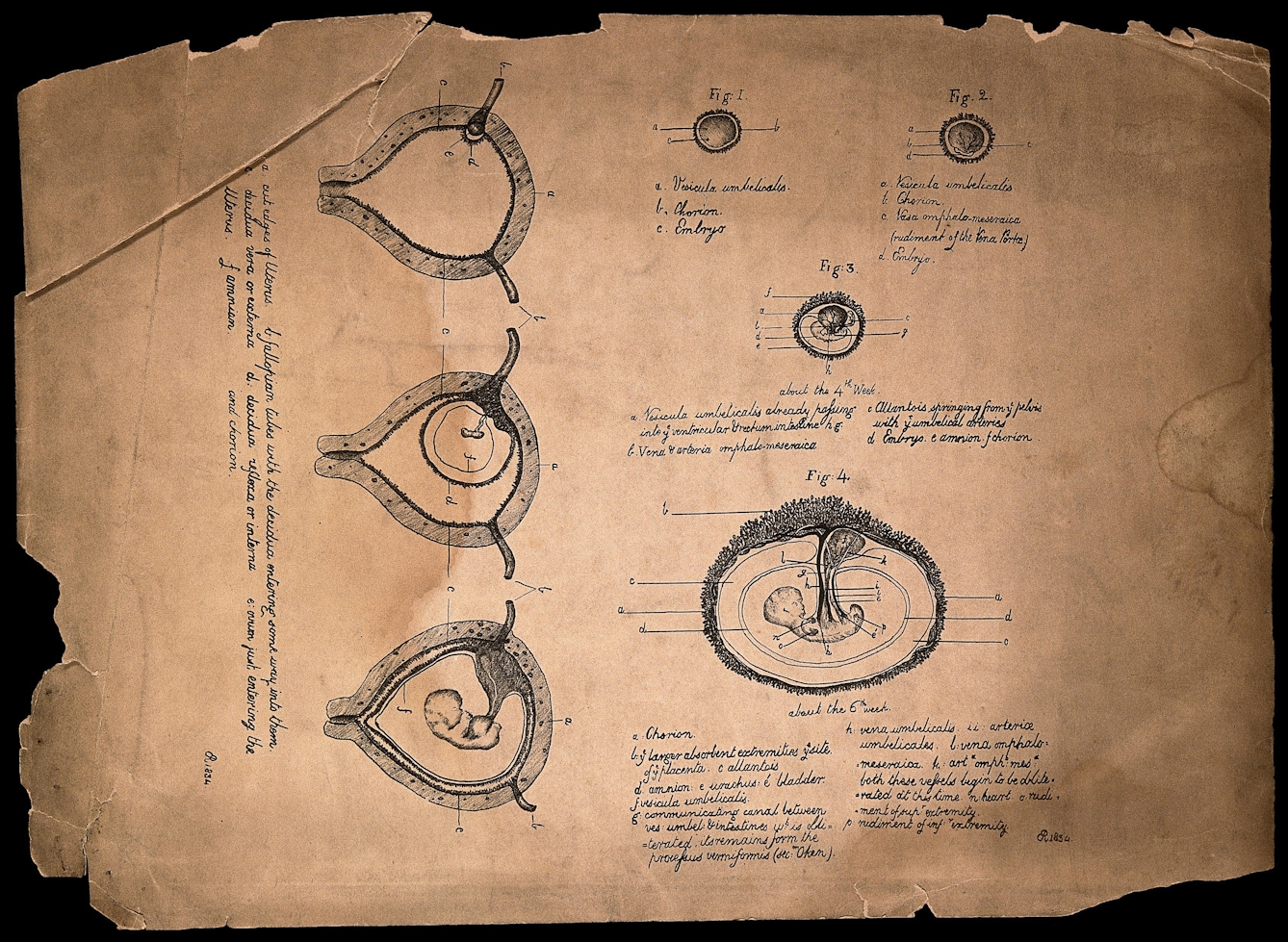

When images of the foetus relied on dissection for their accuracy, it meant that pregnancy could only be observed when it was visible to the naked eye. The development of increasingly accurate microscopes and lenses meant that the study of the foetus could be pushed back to its earliest embryonic phases. This image from 1834 shows the early embryo in its yolk sac embedding itself in the wall of the uterus. These changes, happening in the first few weeks of pregnancy, would be before most women even knew for certain they were pregnant.

Women’s diaries, letters, novels and poems across the centuries have often referred to the unborn baby as “the little stranger”: the person in their bodies, invisible and hidden, was largely unknown. In early pregnancy the idea that a baby was there at all had to be taken on trust. Increasingly, however, scientific instruments allowed early pregnancy to be rendered visible. This meant not only the use of microscopes, but of stethoscopes to hear the foetal heart and, from 1896, the use of X-ray to ‘see’ the living foetus.

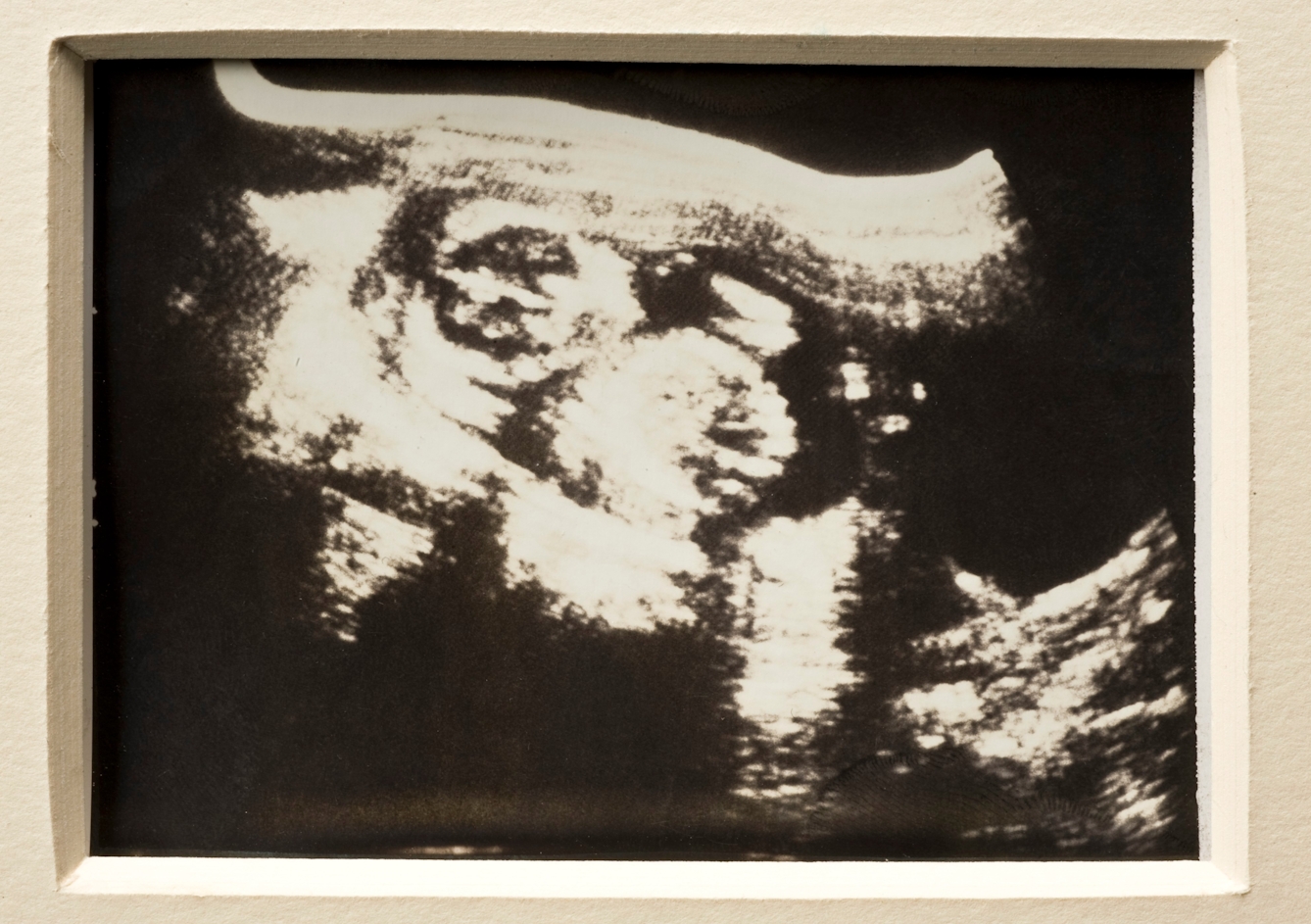

This hazy black-and-white ultrasound image taken in 1981 has nothing like the clarity of 18th-century engravings or even of 16th-century woodcuts. Ultrasound for use in pregnancy was developed in the 1960s and became a “window into the womb”. Initially developed without a clear idea of how it might be used, ultrasound became popular with doctors for deciding how advanced the pregnancy was, estimating the probable date of birth, assessing the number of foetuses, and for observing major abnormalities. For many families since the late 1980s, one of the main advantages of the scan is to tell them the sex of the baby before birth.

The modern familiarity of the foetal form is used in a variety of different ways, including this anti-smoking public health aid. The model of the foetus is used to illustrate the effects of smoking to pregnant women, telling them that their behaviour can make the uterus a place of danger. The image makes explicit the idea that the uterus is no longer just a vessel for the foetus, but that the intrauterine environment can have an impact on foetal health.

We have become used to the visibility of the foetus in the 21st century. Ultrasound scans have become part of routine pregnancy care, and pregnancy announcements are often made by putting scan pictures on social media. As these images remind us, people have always sought to ‘see’ the foetus before birth. They have done this for many reasons, including education, considering how best to help the baby into the outside world, and scientific curiosity. More recently, ultrasound scans have been used by obstetricians for diagnostic purposes, and by women and families for reassurance, bonding and planning.

About the author

Tania Staras

Tania Staras is a midwife and historian currently based at the University of Brighton, where she teaches student midwives. Her research interests focus on histories of midwifery and childbirth.