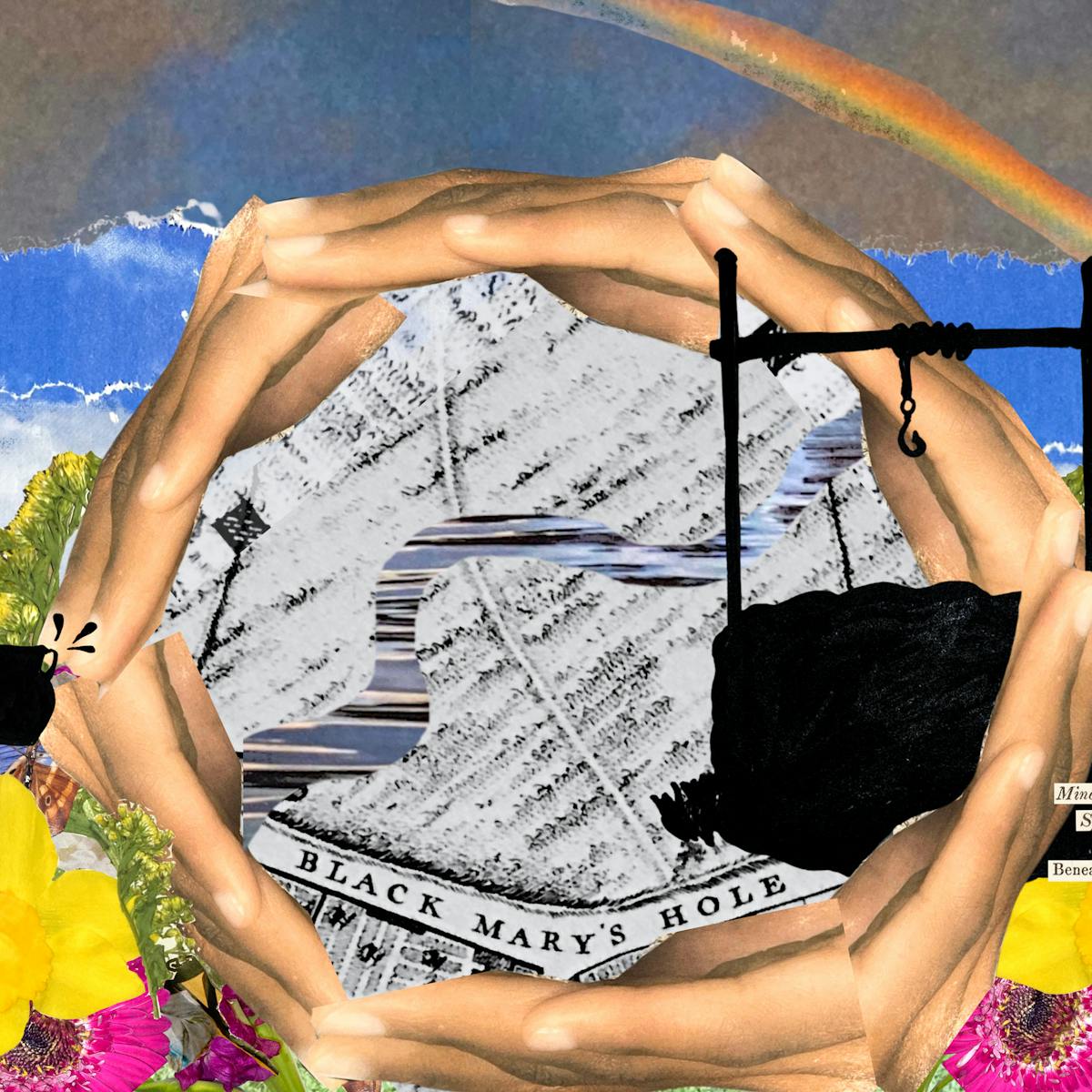

In this extract from the anthology ‘Thirst’, Gaylene Gould uncovers the story of Black Mary, a 17th-century Black woman healer who sold water from a now-lost well.

In search of Black Mary

Words by Gaylene Gouldartwork by Funmi Lijaduaverage reading time 8 minutes

- Book extract

I’ve been without water or heating for three days now and it’s the dead of winter. My whole block is without water, in fact the entire street. Thames Water are desperately trying to fix a slew of problems – from a broken valve in Brixton to air bubbles in the pipes that had turned our water suspiciously cloudy – and have now staunched the flow entirely.

My neighbours and I are filling buckets with water from an outside standpipe to flush our toilets and scouring shop shelves for bottles of water to drink. We are huddling in our single rooms around electric heaters and I’m grimy from not having washed properly for a few days.

I’m extraordinarily lucky that throughout my lifetime water has been available at the turn of a tap and I’m confident that this situation will be short-lived – so why am I gripped by a primal sense of terror?

Thames Water, and other water companies, have been trending of late. Stories of failing infrastructure, pollution pumped into rivers, and a company on the brink of financial collapse have kept London’s primary water company in the headlines.

There are many roots to this cataclysmic situation, including higher levels of rainfall flooding the system. However, private ownership is clearly not helping. The profits that should be spent on necessary upgrades are being split with shareholders. I realise that my growing sense of alarm is not for this situation alone but in anticipation of a future of forced thirst.

The lost rivers and healing wells of London

London’s landscape, its rises and falls, is shaped by the memory of its rivers, many of which flow unseen. The River Fleet is one such.

Since Roman times, the Fleet has run from the north of the city, now Hampstead, issuing into the Thames at Blackfriars. Today the Fleet continues to flow down this route as part of the sewer system and beneath generations of concrete.

Outside a pub on Clerkenwell Road you can still see, hear and feel the power of the rushing river through a grate in the pavement. This river was once known as the River of Wells because it fed healing water wells along its banks. The healing water, or chalybeate, came about by the river water mingling with the dense, mineral-rich London clay.

In the 1600s there was a well fed by these healing waters, known as Black Mary’s Well, situated in a marshy rural area, now modern-day King’s Cross.

“A 17th-century Black woman healer who sold water from a now-lost well—her name embedded into the landscape long after she disappeared.”

The eponymous Mary is a legend. There are many conflicting accounts of the mysterious woman whose name was embedded into the landscape long after she disappeared. The best description can be found in Thomas Cromwell’s 1828 book ‘History and Description of the Parish of Clerkenwell’:

“Beneath the front garden of a house in Spring Place, and extending under the foot-pavement almost to the turnpike-gate called the Pantheon Gate, lies the capacious receptacle of a Mineral Spring, which in former times was in considerable repute, both as a chalybeate, and for its supposed efficacy in the cure of sore eyes. [. . .]

About one hundred and forty years since, it was the occasion of giving the elegant epithet of Black Mary’s Hole to a small old house on this, and a few others on the opposite side of the road, from the following circumstance. In the single house eastward of the road [. . .] immediately contiguous to the fountain, lived a black woman named Mary Woolaston, who rented this spring, or conduit, of Robert Harvey, Esq., and made a living by the sale of its water to the citizens.”

There are sightings of Mary Woolaston, or Black Mary, in other historical records. Some question her existence. The trail quickly runs cold. There are descriptions of the healing wells – but most from 100 years or so after Mary’s era, when the wells had become a commercialised part of London’s social fabric.

The wells seemed to have served the mixed function of a place for healing and a lively social hangout. They were accessible places for everyone – rich and poor – and were often lively and rambunctious.

Given that the well-keepers would have held space for a broad community of people with physical, mental and social needs, the work must have been fascinating. Yet there is little on record about their lives. We do know about the men who profited from the waters, however. Their lives are well documented.

The most prestigious ‘man of water’ of the time was undoubtedly Hugh Myddelton. In 1613, Myddelton opened London’s first water station, right behind Mary’s spring at around the time she was alive.

The New River Head miraculously pumped clean water into London via a conduit from Hertfordshire, an engineering feat spearheaded thanks to Myddelton’s powerful connections.

“The wells seemed to have served the mixed function of a place for healing and a lively social hangout, accessible to everyone—rich and poor alike.”

To fund the New River Head, the Myddeltons created one of the first joint-stock utility companies, basically a company led by shareholders, which turned water into a capitalist venture for the first time.

While it’s nigh impossible to find information about the independent working well-keepers like Mary Woolaston, there are multiple streets, squares and statues in honour of Hugh Myddelton.

And the New River Head? Well, that became the Metropolitan Water Board, which in turn became Thames Water.

Who was Black Mary?

I’d first read about Mary Woolaston in my friend Nana Ocran’s 2003 guide ‘Experience Black London’. Today such a guide would be researched and shared online. But this was a few years before the internet had become a global archive. It was also many years before historian David Olusoga would appear on primetime TV popularising Black history.

Now, when I read the small paragraph that captivated me back then, it’s hard to fathom why this section stuck. “‘Black Mary’s Hole” was a lonely spot on the road from London to Hampstead near Cold Bath Fields. The place was named after “a Blackamoor woman” called Mary, who lived by the side of the road in a small hut built with stones.’

There were mentions of the extraordinary freedom-fighter Olaudah Equiano and Henry VIII’s court musician John Blanke, but it was the image of this mysterious Black woman, living freely by the side of a road named after her, that seeped into me.

Over the next twenty years, I continued to search for traces of Mary. The more information I unearthed, the more my obsessions were compounded.

There were healing water wells in London and one kept by a Black woman? Who was she? Where did she come from? What drew her to this place and work?

Rediscovering Black Mary’s Hole

It was a bright and brisk November day in the wake of the pandemic when we went in search of Black Mary’s Hole. Recovering the memory of public healing spaces now felt like an urgent and vital endeavour. The world was in need and it was time to find Mary.

“Running beneath us... was a small stream that seemed like an impossibility in this time and in the place that London has become. And yet here she was.”

We had scoured the internet for clues as to where the well might be and Zaynab, my friend and project producer, had sketched out a potential route that might lead us there.

We started at Farringdon Station, a surprisingly bustling area in the heart of old London. Pret a Manger eateries were jammed up against 400-year-old pubs, leaving us disoriented in time. This is the inner city, parched, traffic-clogged, with some of the worst air pollution in London and with absolutely no evidence of water, healing or otherwise.

Farringdon Road became King’s Cross Road – a main north–south artery, and one of the most noise-polluted. At times we had to raise our voices to be heard above the thundering lorries as we walked beside each other. Even though I’ve lived in London for over thirty years I’ve never got used to the constant racket of the city, so when Zaynab led us off the main road on to the surprisingly quiet Conduit Street I was relieved.

There were clues. The shift in quiet on Conduit Street, the soft bend of the road, like a river might make. We spoke about the way in which the memory of water marks our contemporary landscape in street names like Conduit and look, there! Wells Street.

I didn’t know then that the Fleet was running beneath our feet, and maybe it was this that was causing me to tremble. ‘She was close to here,’ I said, surprising myself. ‘I can feel it.’

We allowed our instincts to lead us on, rounding the corner on to Calthorpe Street, a tidy strip of Georgian houses, an inexplicable sense of excitement growing.

As we turned down the street our attention was pulled to the left, towards an inconceivable patch of green. As we walked through the impressive red and black wooden entrance emblazoned with the name Calthorpe Community Garden, the tingling began to settle into another feeling which could only be described as knowing.

We stopped on the wooden bridge that links this timeless garden to the outside. Running beneath us, through a rough and wild sunken garden shielded by tall, cool trees, was a small stream that seemed like an impossibility in this time and in the place that London has become. And yet here she was.

‘Thirst’ is out now.

About the contributors

Gaylene Gould

Gaylene is a socially-engaged artist who affects social change through artistic projects that build communities of care. She is the Lead Artist of The Black Mary Project.

Funmi Lijadu

Funmi Lijadu is a writer, artist and publicist with an interest in social issues, identity and surrealism. She has been commissioned by clients including the Tate and Tinder. Her articles are wide-ranging and tackle issues surrounding culture, gender and climate justice. Her work has been published in Cosmopolitan, gal-dem, Metro UK and many more.