Aegina is a Greek island surrounded by sea but starved of freshwater. Mirela Dialeti reveals how locals survive on tanker deliveries and bottled water, all while hoping a new underwater pipeline will change everything. But old habits and doubts run deep.

It took me some time to answer. It was the kind of question not even a child can address without pausing. “What are you most afraid of?” my mother asked, bathing me with bottled water as I wept beneath the pistachio trees. I was five.

She’d ask this while washing me with the good kind of water, the kind we were meant to drink. I cried because I knew it was precious. I cried because she was pouring it over my head instead of into my mouth. So then, when she asked again, “Why are you crying? What are you afraid of?” I finally had my answer.

Thirst.

The weight of water

Aegina, a small island near Athens, has long struggled with water scarcity despite its proximity to the sea.

In ancient times, water was supplied to the city via an aqueduct system. It gathered rainwater from surrounding mountains and tapped into groundwater from natural springs, storing it in a central reservoir before channelling it to the city. The entire island was riddled with underground passages from which water was carefully managed and distributed.

Later, in the 19th century, the island’s villages relied on cisterns that captured rain, 30-metre-deep pits, or natural springs for water. In the town, water flowed through an aqueduct and was distributed via public fountains – open only a day or two each week until the 1950s. You lined up with your jug and waited your turn. Water was not just a utility but a ceremonial routine.

By the 1960s, boreholes had spread across the island. They provided expensive, salty water, fit for tomatoes and goats, but rarely for mouths. Tankers filled the gap.

“The island smelled of pistachios and sunshine.”

‘Nerouládes’ – or water men – shipped water in large tankers from the mainland, often from the Peloponnese. Their arrivals defined summers as much as ferries from Piraeus: ships docked, hoses snaked ashore, barrels emptied into municipal storage. It was an economy as much as an emergency: water bought, sold, delivered, counted. A lifeline, but one you paid for. Dependence hardened into routine.

Between pistachios and plastic: Growing up on Aegina

My childhood summers in Aegina were framed by this paradox of abundance and scarcity. The island smelled of pistachios and sunshine. I spent endless days at the beach, enjoying siestas that left my skin sticky with salt, epic bicycle races, and nights dipping into the sea under a cooling sky. Water was everywhere – it grew the trees, carried us in the sea, gave us our playground. It shaped our lives, comforted us, held us, and gave us immense joy. We were strong swimmers, nimble divers, children of its salt and play.

But here lies the contradiction: in Aegina, water was also what we lacked. At least, not the kind we could drink. The taps, when they flowed, carried water that was good enough for tomatoes or sheep, sometimes good enough for washing, but never good enough to consume. So, locals developed a set of rules: don’t open your mouth in the shower, don’t trust the taps, don’t touch the springs. That’s how it was – and, in many ways, still is.

Every summer began with the supermarket pilgrimage: crates of bottled water stacked higher than we were tall. Tourists breezed through checkouts beside us, oblivious that the clear plastic in our carts wasn't a convenience, but our lifeline. Behind hotels, plastic bottles ballooned into informal monuments – bright graves for a resource we could not trust from our taps.

A pipe dream

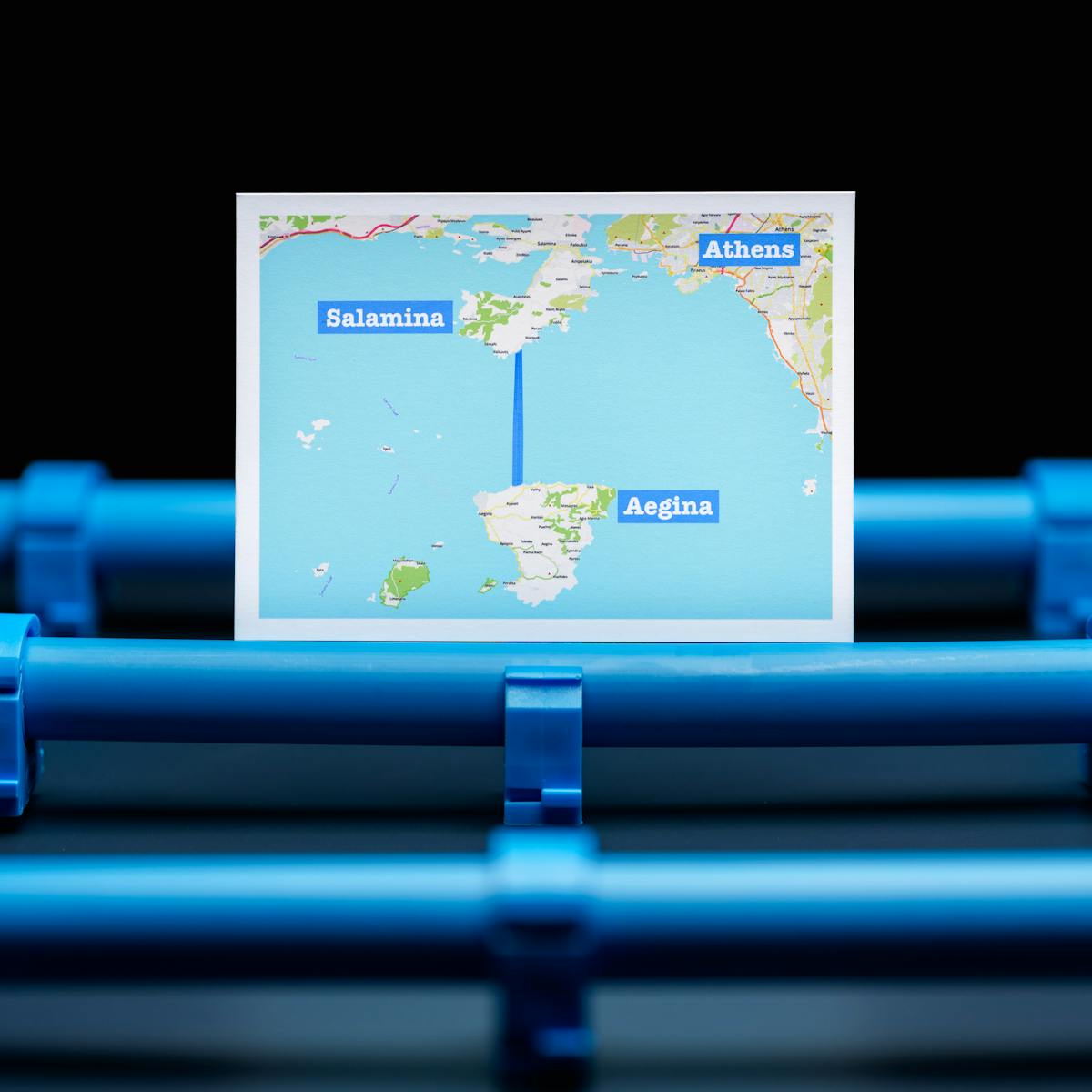

In 2020, Aegina installed what felt like a lifeline: a nearly 15-kilometre undersea pipeline from Salamina, lying 94 meters beneath the Saronic waves. It was hailed as “one of a kind” for Greece – a technological feat finally delivering drinkable water directly to our taps from the mainland. For locals, it promised something long overdue: an end to summer pilgrimages for bottled water, the beginning of water independence, and relief from the plastic tide.

“My childhood summers in Aegina were framed by this paradox of abundance and scarcity.”

But the pipeline’s promise would soon be tested. Since its inauguration, the pipeline has suffered multiple ruptures. The first occurred during construction in 2020 – holes drilled as though in a protest, delaying completion. Then came two more blows in 2022: one explosive crater near Salamina, another at depth – planted, divers say, far from shore, deliberate and precise.

And just when the hope seemed real, in early 2024, the pipeline failed again. Attica’s regional governor, Nikos Hardalias, called it the fourth “act of sabotage” and asked prosecutors to investigate, while delivering 13.5 tonnes of emergency bottled water to the most vulnerable. These disruptions have fuelled suspicion of interference by the nerouládes who profit from shipping water in large tankers from the mainland to the islands. While Aegina’s mayor offered a different explanation (brittle materials, perhaps poor installation – not sabotage), islanders have been quick to point the finger at the nerouládes who may be unwilling to surrender their lucrative position without a fight. Even with the pipeline operational and all damages repaired, trust has been slow to follow.

“I still don’t touch the tap”, says my friend J., a lifelong resident in his late thirties. “Even when I travel abroad, or when I visit Athens, I carry bottled water with me – it’s a habit from childhood.” Many others share his caution. In restaurants, when asked whether they want tap or bottled water, they laugh and always choose bottled, the old rules lingering in their habits.

A local hotelier quietly keeps a tanker on standby “just in case”, even though the pipeline now promises consistent delivery. “You can’t change decades of caution overnight”, he admits. This cautious approach mirrors a broader sentiment among residents: the infrastructure may have improved, but trust is a slow creature.

The plastic tide

The dependency on tanker-delivered water indirectly fuelled plastic use. Islanders often transferred the tanker water into smaller bottles for daily consumption, reinforcing a broader, persistent reliance on bottled water.

But that wasn’t the only reason plastic entered daily life. Water from the nerouládes was often distrusted and seen as unreliable for drinking. What began as a response to genuine quality concerns slowly became habit, fuelling reliance on bottled water that gradually replaced the island’s traditional sources – cisterns, springs and boreholes. Whether drawn from tanker water decanted into bottles or purchased from shops, bottled water became the default for drinking. And with it came the swell of plastic.

“The infrastructure may have improved, but trust is a slow creature.”

Greece produces roughly 700,000 tonnes of plastic waste each year – about 68 kilograms per person – with tourist seasons pushing that figure up by as much as 26 percent. It is the sixth highest consumer of bottled water per person in the EU, which is significantly greater on the islands than in the country at large where tap water is mostly drinkable. On Aegina alone, the scale of consumption is striking: a single taverna can go through around 25,000 plastic bottles in a month. This pervasive presence of plastic bottles serves as a constant reminder of how intertwined our daily survival is with the complex environmental legacy we inherit.

Beyond Aegina

Aegina isn’t alone. Across the Aegean Sea, islands like Patmos, Serifos, the smaller Cyclades and even parts of Crete still rely on water ships while hoping for more permanent infrastructure solutions. Geography makes them dry; tourism makes them thirsty; politics keeps them waiting. Tankers fill the gap, and with them comes a quiet but inefficient economy that no one is in a hurry to give up. Business contracts are extremely lucrative, and local intermediaries also profit. Dependence has its beneficiaries.

There are other solutions – desalination, draining water from cisterns during Mediterranean storms – but these remain more promise than practice. It is easier to roll in the tanker, easier to stack the bottles, easier to keep things as they are.

Standing barefoot on the island today, I reach for a bottle of water that I trust because it has been sealed, packaged, transported. Below, the pipeline whispers a promise of water flowing freely, unbroken, untainted. Above, on the island itself, life still leans on plastic bottles stacked like small fortresses, each one a concession to habit and doubt. I lift the bottle to drink and feel the tug of decades of scarcity in my hand. The sun above Aegina is the same as it was 20 years ago: relentless and warm. Somewhere between the pipe below and the bottle in my hand, hope and reality intertwine. Each sip a quiet negotiation between the freedom promised and the waiting game of reality.

Water surrounds us, shapes us, sustains us, controls us. Yet still, we reach for it.

About the contributors

Mirela Dialeti

Mirela is a Brussels-based legal and communications professional from Greece with a background in journalism and investigative reporting. Her work focuses on EU policymaking, digital rights and bias in emerging AI technologies, democratic participation, and arts and culture.

Steven Pocock

Steven is a photographer at Wellcome. His photography takes inspiration from the museum’s rich and varied collections. He enjoys collaborating on creative projects and taking them to imaginative places.