Fertility treatment is physically and emotionally arduous, with no guarantees. Artist Jessa Fairbrother’s options hadn’t run out but her capacity for uncertainty and grief had. It was time to let go of the idea that motherhood would make life more meaningful. Here Jessa describes the decision not to have IVF and the complexity of living with that choice.

Let me tell you the ending straight away: there is no baby. After several miscarriages, some related fertility treatment, a lot of prodding from medical professionals and the death of my mum, I decided not to go through with IVF. This decision was not because I’d run out of options. I chose not to have treatment and to get on with my life instead.

A few years earlier…

In late 2010, my husband and I decided to stop using contraception and “see what happened”.

I got pregnant after a couple of months but had an early miscarriage. The baby stopped growing at some point between zero and seven weeks (formally noted as six weeks plus five days).

I analysed every moment. I'd drunk alcohol and danced energetically; I’d gone for a pathetically slow jog; I’d moved heavy objects and accepted a flu jab. I thought these things made it my fault. I'd done this to myself and our baby.

A year passed without another pregnancy. I began hassling my GP, who finally stopped telling me to relax and did some referrals.

Around about then, my mum had a strange pain in her side. After an X-ray and ominous talk of shadows and sclerotic tissue, I arrived for the weekend to take her for a CT scan, realising I might also be having another miscarriage. I did a pregnancy test and a weak positive appeared, which was followed by a heavy period.

I didn’t know whether to tell my GP about the miscarriage. I was frightened they wouldn’t continue to refer me for fertility investigations. I didn’t have time to process any of it anyway because it turned out my mum had lung cancer and was going to die.

I moved 180 miles to care for her, filtering out information she didn’t want to hear about all sorts of things. On a walk, she asked me what names I liked for babies and told me one she liked. I knew she was trying to place herself in a future part of my life that she wouldn’t see.

I couldn’t bear how long it took to transfer information about my fertility between health authorities. I started making enquiries while living in Sheffield but had since registered at the same GP surgery as my mother in Bristol and hoped they’d be able to pick up the investigation process.

I paid privately to have my uterus scanned to see if there was anything that might show why I wasn’t conceiving. It didn’t. I tried acupuncture. I counted out the months in which it might be possible, if I got pregnant, that my mother would meet my baby. One by one they slipped past and I knew that she wouldn’t.

My mother died when I was 37 and a half. My father had already died from cancer 11 years earlier. I know they were meant to go before me, but not so soon. Not when I couldn’t conceive and become a parent myself.

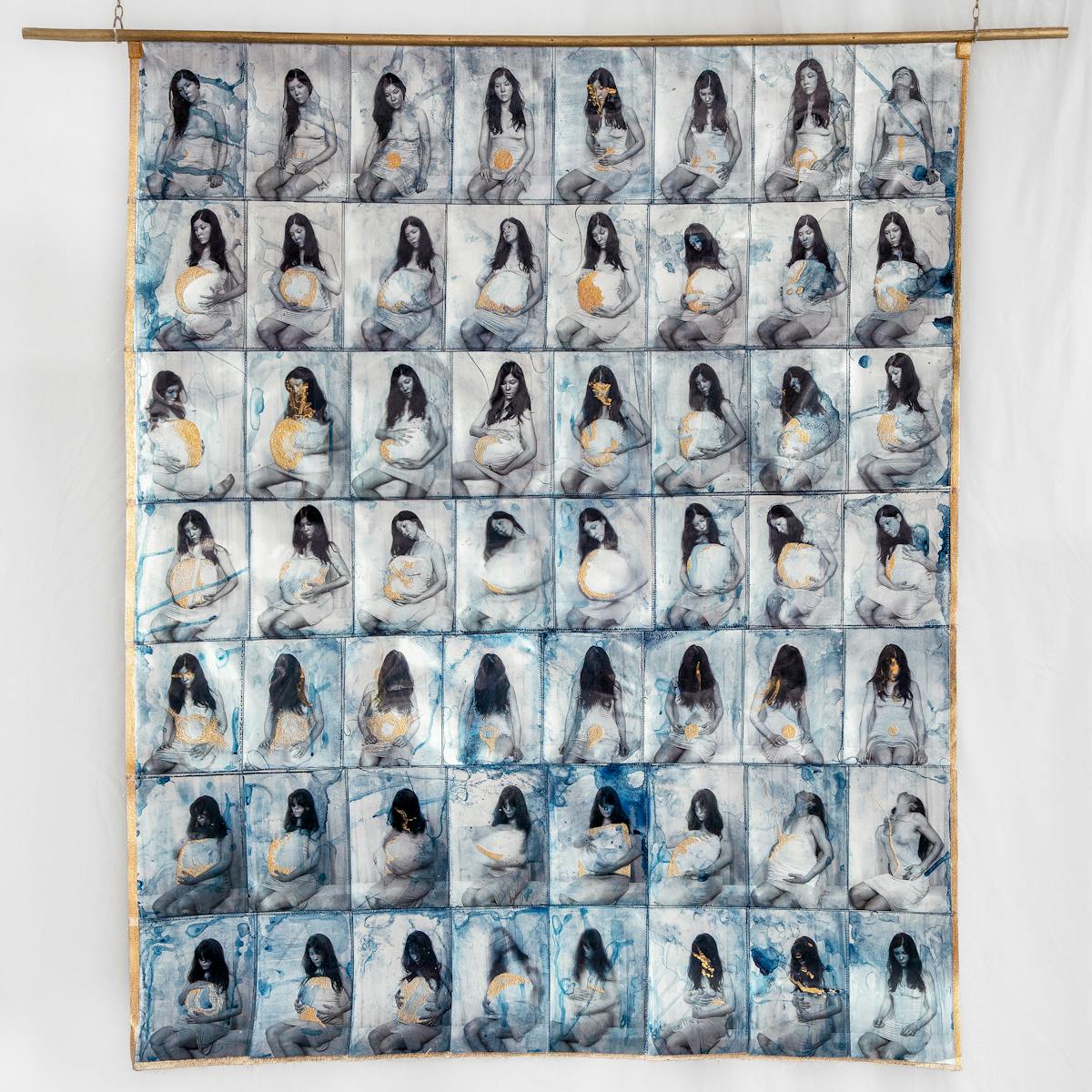

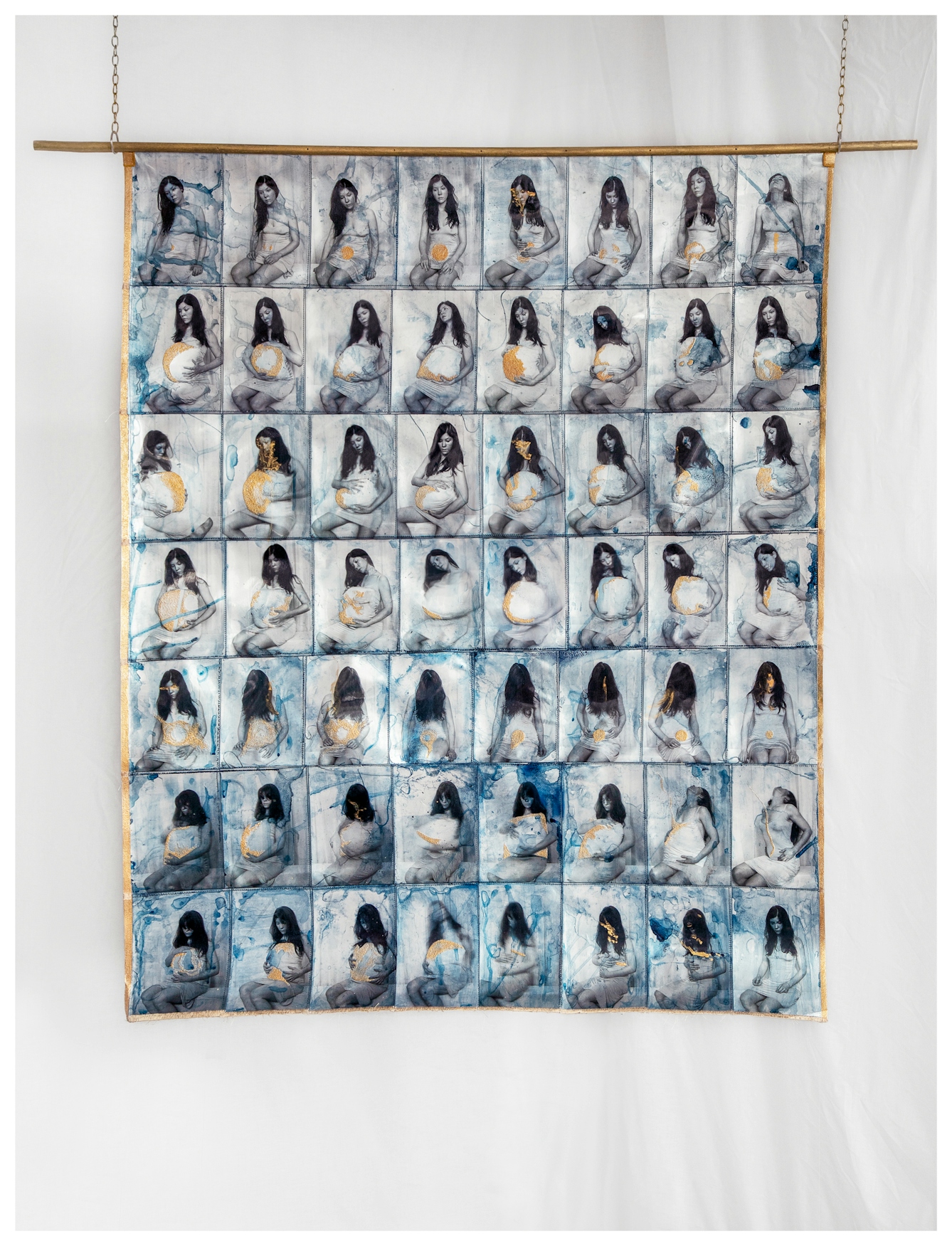

Detail from ‘Role Play (Woman with Cushion)’ by Jessa Fairbrother.

The fertility treatment gamble

In my new postcode we qualified for one cycle of NHS-funded IVF and three rounds of less invasive intrauterine insemination (IUI). I was nearing the age limit for funded treatment, and it didn’t feel like I could put it off to grieve for my mother. Two weeks after her funeral – on Christmas Eve – I was in hospital having both a hysteroscopy (a look inside my womb) and laparoscopy (a type of keyhole surgery). They found a polyp in my uterus but nothing that explained why I couldn’t get pregnant.

The next few months were extremely hard. I was consumed by anxiety and grief, but I didn’t have time to wait out bereavement. The consultant said I could go straight to IVF, but I thought it would be a waste of a ‘go’ and opted for IUI first. I took hormones, did some injections, had my ovaries scanned a few times and my husband’s sperm inserted through a catheter into my uterus.

Fertility treatment involves a lot of internal scans. I stared at the ultrasound screen many times over this first round of IUI, fascinated by little white dots representing hopes, dreams and disappointments.

I scoured the internet for information, reading sad stories about journeys to parenthood: forums of women keeping and sharing detailed records of temperatures, fluids, twinges and emotions. I lost myself in it all, searching for similarities, things to explain what was happening to me.

Immersed in other people’s misery, it was literally beyond my understanding how anyone got pregnant at all. The NHS offered three free fertility counselling sessions. It’s hard to remember but I think maybe I went to one. I felt like I had nothing to say except, “This is truly awful.”

The first round of IUI failed. Then, the second round. And the third. I’m still not really sure what the point of IUI is for women like me. It just felt like medicalised turkey basting with variable odds.

We were sent to an information evening where a fertility consultant explained the minutiae of the IVF procedure. We sat in a room with lots of other couples. No one really looked at each other. It was a room of sadness, desperation and hope.

By now I was 38. I had found the IUI treatments emotionally draining but couldn’t work out if it was because I was sad about my mother or sad about myself – or a mixture of both. I was less and less able to think about the idea of IVF. I wasn’t about to start putting my efforts into funding further treatment if the first round of treatment failed. I was already sure I wasn’t going to gamble tens of thousands of pounds and years of my life on a quest for a baby.

The last chance saloon

I was never particularly maternal as a younger woman. I hadn’t yearned for kids through my twenties. When I reached my mid-thirties, I knew I had a lot of love to give to a child, as my mother had given me. Somehow I’d been seduced by the myth that parenthood would make me feel fulfilled.

I kept crying about my own mother. I cried for her touch, for her laugh. I cried because she would never be a grandmother. She’d never bounce my baby on her knee, and we’d never push a pram around the park together. I felt angry when I saw other women doing that. I was jealous.

Detail from ‘Role Play (Woman with Cushion)’ by Jessa Fairbrother.

My husband and I worked out that we had a small amount of time in which we could forget about IVF. We went on a summer holiday, pretending it was the last proper break we’d have for 20 years, both of us secretly hoping I would get pregnant naturally.

I contacted the clinic that autumn and discovered we’d left it so long we’d have to have a range of tests again. We were frustrated but had the required samples taken and results recorded.

And then, eventually, we were given permission to start this final precious IVF treatment. The process started with fertility drugs designed to suppress and take over my hormonal system. I was given instructions on how to use the combination of carefully timed nasal sprays and injections to stimulate my ovaries to a controlled timetable.

This took its toll both physically and emotionally, narrowing my daily activities to anti-social basics. I barely went out. I refused invitations from friends. I was petrified of catching a cold – anything that might stop the treatment from working.

After a certain number of days, I was expected to have a ‘bleed’ – something that has to occur before starting injections that force your ovaries into overdrive, so they produce lots of eggs at once. Except I didn’t have a bleed.

I went to the clinic. They said to ring a few days later if I still hadn’t had one. I spent a day with terrible backache and, with a hunch, did a pregnancy test. It was positive.

Having tried timed intercourse, peeing on sticks, hot water bottles, putting my legs above my head, acupuncture and attempts to ‘forget about it’, here I was in a last-chance saloon conceiving while taking hormones to suppress my system.

And then, 10 days later, I lost it.

I felt the familiar cramps and knew straight away what it was. Two days after that it was over.

Fertility specialists said I could just start the cycle again as I had not begun my final injections – technically it had not been a ‘confirmed’ pregnancy, so it did not affect my funded treatment. I pointed out this was the third miscarriage in a row. Shouldn’t they check something before I did the final injections? Shouldn’t they do it right away because I wasn’t far off being 40?

I made a fuss. I highlighted miscarriage number two, so early I hadn’t bothered reporting it in great detail to anyone at the time, distracted as I was by my mother dying. I was sent to another clinic for more tests including the one for chromosome abnormalities.

Detail from ‘Role Play (Woman with Cushion)’ by Jessa Fairbrother.

I waited. I rang every medical secretary I could get hold of in various clinics, with no success. I tried to get booked in for IVF before the results came back, now feeling certain they’d show nothing at all and reasoning that at least I’d be in the system so there would be no delay. The secretary at the clinic wouldn’t do it, citing guidelines, ethics and plain queue-jumping morals.

I cried on the phone and said, “If I can’t do it now, I’m not going to do it.”

And the woman on the other end of the line said, “That’s your choice.”

I knew I was being over the top but she was right. It was my choice. I didn’t have to do it. It was what was available. But that’s not the same as it being the right thing. I knew, deep down, I didn’t want to do it anymore – whatever the test results said.

I stopped hassling for information, eventually getting a hospital letter saying nothing was wrong. There was no reason why I couldn’t get pregnant.

By then I had thought about it so much, and I was in so much grief, I decided I didn’t want to put myself through any IVF cycle. I was obviously depressed but there was no help for that. I staggered along on my own. It seems ridiculous looking back.

I rationalised. I told myself it was highly unlikely IVF would work anyway. I would either not get pregnant, or I would get pregnant and lose it, or maybe I would get pregnant and have a baby with additional needs because I was an older woman.

And then I realised something even more painful: I didn’t want to get pregnant because I just couldn’t bear it. Something in me had changed when this little speck left my body. It felt like biologically giving birth wasn’t going to be part of my story – that I had a different story ahead of me.

Choosing not to start

It wasn’t until some months later that I realised none of the doctors ever asked me if I still wanted to do the IVF. I wish they had. Do all doctors assume that, if you have got so far, you must really want it? Do they stop asking you in the consulting room because they offer fertility counselling adjacent to your treatment instead? Who’s meant to ask you? Are you just meant to know?

It feels increasingly strange that the only time I had any aspect of that type of conversation – in medical terms – was my brief, frustrated exchange on the telephone with an anonymous medical secretary. I have often thought about how much impact that had. I am sure she will have had no idea. But that was the contact. That was it.

‘Role Play (Woman with Cushion)’ by Jessa Fairbrother.

I have always felt a crucial difference between choosing not to take a treatment and it failing after trying. When my parents were told they were going to die from cancer, 11 years apart, they each accepted offers of chemotherapy. I watched as they lost their hair or themselves in sickness, nausea and despair.

It was the standard treatment and they were striving to live. It didn’t mean it was the best thing for them to do. They were both still going to die. I personally think chemotherapy made the end more awful for them. But they chose it. They decided that it was right to take the treatment and that was their choice to make.

I thought about this in relation to the IVF that was offered to me. It was an available treatment but not necessarily what I should be doing. I didn’t want to sit in hospital waiting rooms anymore. Being pregnant and holding a biological creation of my own was not validation for my life.

The complexity of loss

There is such complexity surrounding the journey to motherhood – one that may or may not result in a child. It’s amazing how little we talk about it, even with close friends. I continue to feel huge sadness about my own.

At the time, I took the position that changing my mind was preferable to the experience of IVF failing, even though the outcome would have very likely been the same. I want to believe it was definitely ok to change my mind. I did not have to live with another loss; I could just live.

There are so many stories about baby loss that are heartbreaking. You are more than likely sitting next to someone on the bus or perhaps standing next to a person in the supermarket who holds the most incredibly sad experience in their heart.

I wish I could just let go of a lot of my own stories. It feels very hard to describe the effect of miscarriage and subsequently not having children because there is no ‘thing’ to mourn. No one can visualise the complexity of that loss because there is no physical evidence for it. It is even harder to explain how, on top of that, you changed your mind as well.

There is only a shape of something in my thoughts of what was or wasn’t there, like a small shadow that slips out of view when the sun dips behind the roof. The most positive part of these last ten years has been embracing that I had the power to choose. Which I did.

About the artwork

Following extensive medical investigations and three miscarriages, I reconsidered IVF. I initially tried expressing my emotions through art, mimicking pregnancy with a cushion and wearing my grandmother’s dress, but I stopped due to the emotional strain. After my mother’s death, I found photographs from 1975 of her pregnant, which inspired ‘Role Play (Woman with Cushion)’. In this work, I performed pregnancy for the camera, exploring my connection to my mother and grandmother through hand-stitched art.

About the author

Jessa Fairbrother

Jessa Fairbrother is an award-winning artist concentrating on themes of yearning and the porous body. Initially training as an actor, she later completed an MA in Photographic Studies, amplifying her knowledge of how artwork and audience collide. Jessa uses embroidery, performance, photography and writing in her work. The artist’s book of her work, ‘Conversations with my mother’, is held in collections including Tate Britain and the V&A, London. Her companion piece, ‘Role Play (Woman with Cushion)’, is part of ‘Acts of Creation: On Art and Motherhood’ – a Hayward Touring exhibition curated by Hettie Judah.