Researcher Jude Seal examines the evidence for signing in Medieval Europe and reveals a long history of communicating with hand signs among both deaf and hearing communities.

I have studied deafness in the Middle Ages for over a decade, and one of my most frequently asked questions is how people with hearing loss communicated in the past.

In some senses, deaf history has been shaped by the preconceptions of late 19th- and early 20th-century researchers and educators who largely ignored evidence of deaf communication in past societies and dismissed the value of non-verbal communication such as sign language.

Medieval definitions

Medieval texts used Latin terms for deafness and mutism, often interchangeably. Some texts might be titled 'mute' while the entry referred to the person as deaf, and vice versa. Some authors made distinctions between people who were speechless or deaf from birth and people who lost the ability to hear or speak later in life.

While we cannot ascertain whether these individuals align with modern definitions of deafness or mutism, the texts offer insight into medieval understanding and definitions of hearing loss.

For example, the Latin word ‘surdus’ generally refers to deafness, but in ‘Etymologies’ by Isidore of Seville (c. 560–636 CE) – a combined dictionary and encyclopaedia – the term specifically refers to deafness caused by a blockage of the ears.

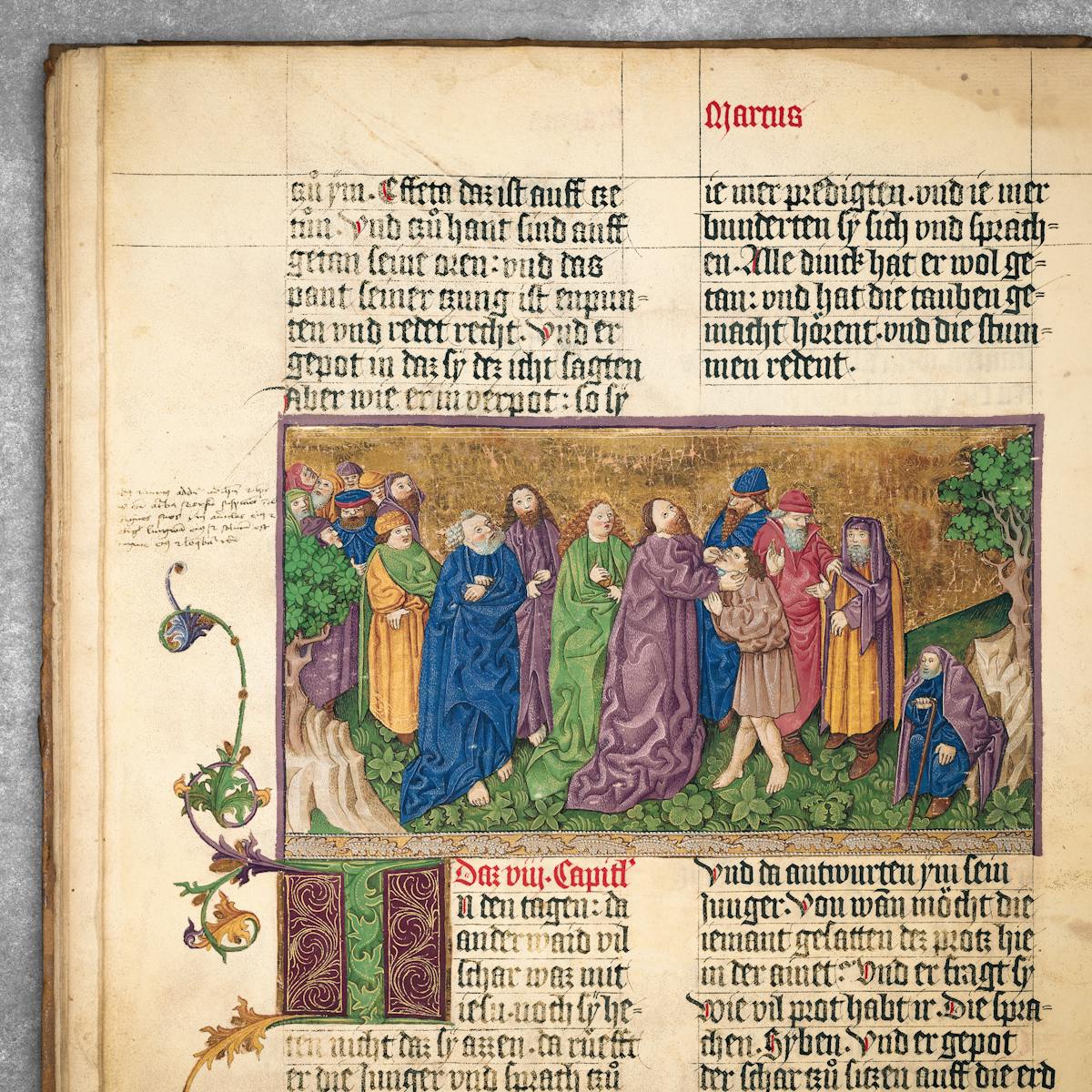

A 15th century German bible illustrating Christ healing a deaf person.

Insight into medieval understanding of deafness can also be gleaned from miracle collections - records of miraculous healings bestowed by saints. The notion that deafness resulted from blocked ears may explain why many records describe the expulsion of matter (usually blood, sometimes worms) from the ears by a saint to restore hearing.

Evidence of deaf communication

The most common descriptions of communication by deaf or hard of hearing people were gestures, facial expressions, movement and sign language.

In one of the earliest sources I studied, the ‘Miracles of St Martin’ by Gregory of Tours (538–94 CE), there are several references to people with deafness and mutism communicating using “three tablets strung together”. Gregory provided frustratingly little detail about this practice, only describing it as an imitation of someone begging.

The phenomenon appears more than once in Gregory's accounts of separate incidents, suggesting that it was a way of drawing attention, perhaps by making noise, to allow for further communication.

Page from a collection of texts relating to St Martin of Tours from the 11th century. The manuscript includes two excerpts the miracles of St Martin by Gregory of Tours.

These communication methods were not widely understood, and deaf people faced many of the same prejudices as today, such as the assumption that limited communication meant a lack of intelligence. In the miracle collection of Gilbert of Sempringham, the author relates the healing of a poor woman named Kenna, who:

"...had long been weighed down by deafness, became so confused from the loss of sensation in her ears that she was considered stupid by some people."

Everyday communication

As is often the case with medieval sources, we know very little about how individuals with hearing or speech loss viewed themselves, and written evidence is constrained to the appearance of deaf people in narratives written by others. However, miracle collections contain numerous references to groups of deaf individuals travelling together and implied they communicated among themselves.

This suggests that there were systems of signed communication in use, with the caveat that such systems were highly localised and would not meet the criteria for formal sign language today. Yet they meant that these individuals were able to communicate and make themselves understood by others, especially members of their own families and local communities.

An illustration from an 11th century manuscript showing a pilgrim setting off on his journey.

In cases when an individual lost their hearing after a specific event, narratives often describe their families bringing them to a shrine for healing, or the individual themself requested such visits, often specifying which shrine. These cases usually refer to gesture and expression as the main means of communication. However, where an individual had been deaf for some time, a form of informal sign language had often developed within the family. This is similar to the phenomenon known as ‘kitchen sign’.

Sign languages

The best records of signed communication in the Middle Ages concern the ‘silent orders’ of monks and nuns, particularly those of the Cluniac traditions. While they do not fit the modern-day stereotype of those who have taken a ‘vow of silence’, these orders placed extreme restrictions on the circumstances in which speech was acceptable and developed broad lexicons of signs in order to go about their day-to-day business.

There is debate over whether these monastic systems were true sign languages or systems of gestural communication. Regardless, they testify to established systems for signed communication which were used by both hearing and deaf individuals.

Concecration of the high altar of the Cluny abbey church by Pope Urban II, 25 october 1190.

The earliest example of monastic sign language comes from Cluny in the 10th century CE. Cluniac monks used signs for bread, fish, water, clothing, bedding, as well as specific books and liturgical objects. It may have been possible that deaf individuals learned these signs from monks and nuns themselves, or were drawn to these institutions, perhaps joining the order themselves.

This language was largely the same across Cluniac houses as they spread throughout Europe, allowing communication between individuals who spoke different languages. While surviving lexicons can only be understood in the context of other monastic records, they demonstrate that sign systems were formalised during the Middle Ages.

The earliest reference to signed language in England is from the marriage of Thomas Tillseye in 1575. The parish register of St. Martins, Leicester, states that in February 1575, a deaf man, Thomas Tillsye, married a woman named Ursula Russel (who was probably hearing), and describes how he made his vows in sign:

"The sayd Thomas, for the expression of his minde, instead of words of his owne accord used these signs: first he embraced her with his armes, and took her by the hande, putt a ring upon her finger and layde his hande upon her harte, and held his handes towardes heaven; and to show his continuance to dwell with her to his lyves ende he did it by closing of his eyes with his handes and digginge out of the earthe with his foote, and pulling as though he would ring a bell with divers other signs approved."

There is clear evidence that the history of sign language goes back much further than many 19th- and 20th-century scholars of deaf education assumed. While we have only fragmentary evidence at this time, further studies are increasing our understanding of the lives of deaf people in the past.

1880 THAT: Christine Sun Kim and Thomas Mader

Discover more about how the recent history of sign language inspired artists Christine Sun Kim and Thomas Mader to create the exhibition '1880 THAT!' at Wellcome Collection. Scroll down to the end of the exhibition page for more stories about sign language and deaf peoples' experiences.

About the author

Jude Seal

Jude Seal is a PhD student at Royal Holloway, University of London, researching the cultural perceptions of blindness, deafness and mutism in English miracle literature between 1070 and 1450. Their research explores the intersection of the histories of medicine and magic, and the archaeology of disease. They also write on living with a brain injury and chronic pain, and in their spare time are involved in disability sport.