Before ‘patient rights’ became common language, one small group in London was already fighting for it. Leona Letts uncovers the story of Needle, the grassroots organisation that gave patients a louder say in their treatment.

Needle(view in catalogue) was a magazine “produced by health workers for health workers”, active from 1970 to 1973. It was started by a group of medical students and doctors who in December 1970 took part in protests against proposed cuts in social and health spending. The group decided to make a magazine to explore innovative ideas in health. Likely influenced by an outpouring of activism in the 1960s and 1970s, Needle held a socialist perspective, reimagining health in a more progressive, person-centred way. Needle was part of what we now call ‘the radical science movement’, which sought to create a new type of science that was more inclusive and democratic, and to protect it from co-option by powerful groups. The movement challenged the prevailing idea that science was neutral and interrogated power dynamics in science.

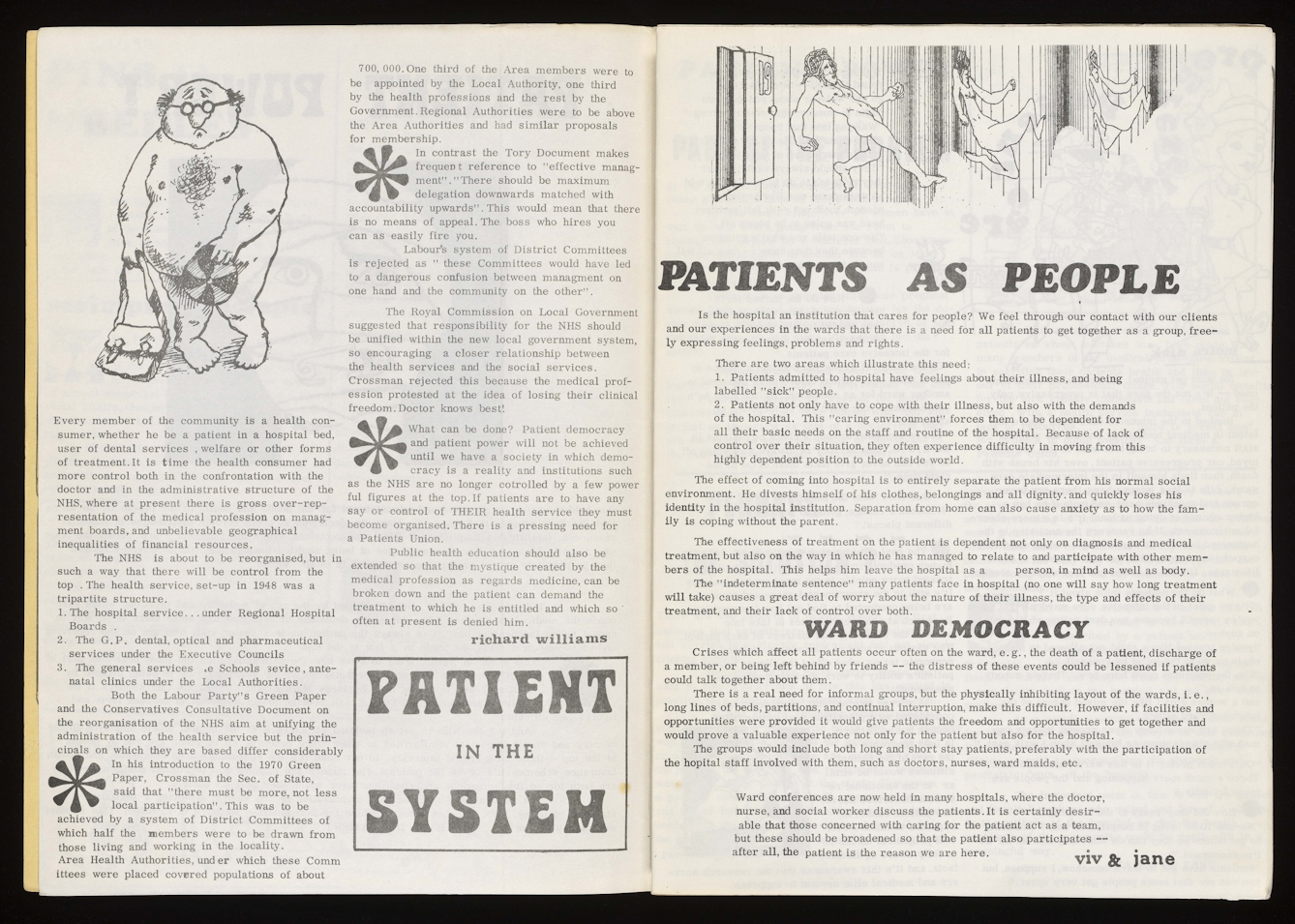

The magazine was produced by a collective of nurses, students, technicians and doctors, who met on Thursday evenings at 27 Pearman street, SE1 in London. It was published roughly every six weeks and was sold quite affordably with a DIY feel. While Needle didn’t have a huge reach, with a circulation of 3,000 people, the magazine is a great window into the creative and radical thinking of health workers in the 1970s. The magazine covered a range of issues such as women’s health, the privatisation of the NHS, racism, mental health and health workers rights. Across the magazine, an emphasis is frequently put on the need for everyday people to shape health services rather than elite groups. For Needle, treating patients with dignity and respect – regardless of their background – and protecting their agency was paramount.

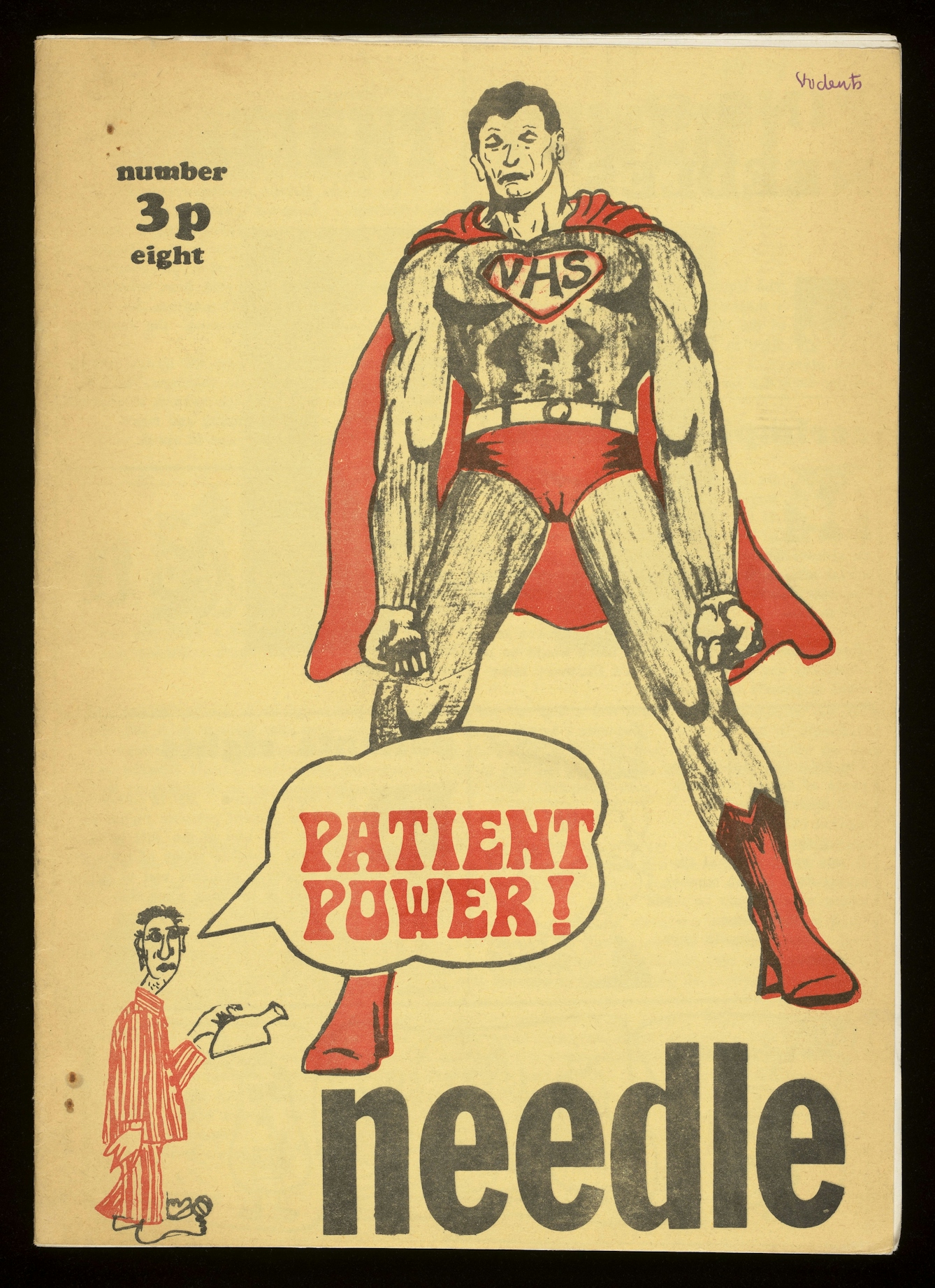

Medical scandals in the late 1960s and 1970s put patient rights in the spotlight – poor-quality care experienced by the elderly and mentally ill at Ely Hospital and Farleigh Hospital hit the headlines. There was also increasing awareness that NHS patients were routinely being used for medical trials without their consent. These high-profile failings prompted action to address the injustices faced by patients. Groups were formed, like the Patients Association, to advocate for better conditions for patients, and assert the rights of the patient as a consumer. As a grassroots group, Needle took a more radical point of view, which was set out in the eighth issue, ‘Patient Power!’ They plainly rejected medical hierarchy and asserted that patients should be the ones driving the direction of health services. This echoes the rallying cry of the disability movement: ‘nothing about us without us’. Needle similarly demanded patients be taken seriously and have a proper say in the care they receive.

In the 70s, it was particularly difficult as there weren’t any legal protections for patients. Attempts to establish a Patients’ Rights Bill failed, and the Patients Charter (which gave patients rights) was only introduced in 1991. As a magazine made by health workers, it’s powerful that Needle gave a platform for patients to talk about how they truly felt when their voices were too often ignored and dismissed. In ‘Patient Power!’, patients described being kept in the dark about their medical treatment, being treated like children, observed by medical students, and treated as a “mere clinical object”. For many people now, these experiences still ring true. I’ve been hurt and disillusioned on behalf of my friends – many of whom are women of colour – who have had their voices and rights as patients disregarded.

While at this time, patient rights activism focused more on the rights of the patient as a consumer, Needle had a strong emphasis on the need to engage patients, health workers and the community in decision-making. For Needle, the exclusion of these groups, and the need to resist their marginalisation, were a connected struggle. Needle explored this at ‘The Controlling Voice’, a conference held at Middlesex Hospital Medical School on 5 and 6 February 1972. Attended by 250 hospital workers across Bristol, London and Leeds, the conference explored democracy in healthcare and highlighted the need to centre patient and public voices. Vocal participants expressed anger at the absence of community control, with a participant pointing out that her “regional hospital board has three knights and two company directors on it”, while another participant questioned “how many MPs will go to a chronic sick ward and listen to complaints?” For Needle, health decisions had to be shaped by the people they directly impact – their needs and perspectives had to be prioritised for better health.

Although patient rights groups were on the rise, a big shift in the NHS in the early 1970s failed to properly engage with such bodies. The 1973 NHS Reorganisation Act changed the NHS – it was now under the control of the Home Secretary. Yet there weren’t any clear routes for patients to feed into this reorganisation of the health service. Before the Act was introduced, only 10 weeks were given for the ‘consultation’ by selected bodies – and this didn’t include patient groups or the public. While patients were shut out, management consultants McKinsey played an influential role in shaping the Act. Needle spoke up strongly against this. For them, this showed that the voices of people who “actually have to suffer the experience of being shuffled through the NHS themselves” were being eroded at the expense of influential groups. Needle’s worry that powerful groups were having too much of an influence on health still has relevance today. Attempts to centralise NHS patient data has led to concerns by community groups and patients that their agency and power is under attack.

As it seemed the government weren’t listening to patients, Needle put forward the idea of a patients union. Likely influenced by the 1972 strikes of miners and ancillary health workers, Needle urged patients to organise among themselves and demand better conditions. From the five issues we have of Needle in our Collection, it does not seem that the patients union came to be. But this proposed solution shows Needle’s fervent belief that patients should have greater control over the health service. Needle not only took inspiration from strikers, but they were also influenced by community-based clinics set up in the United States. Such clinics were staffed by health workers and members of the public. They had a patient committee too, where patients could make decisions on clinic policy. This was a big shift away from the status quo where doctors were the sole experts and key decision-makers, to a more democratic form of organising. Needle urged patients in the UK to take inspiration from across the pond and put patients in the driving seat so they could meaningfully reshape the health service.

Needle strongly advocated for the importance of patient involvement in health decision-making, a principle we now see as integral to good healthcare. While it is unclear whether Needle were able to set up patient groups or a patient union, their ideas and efforts to circulate them gave a voice and platform to patients. Needle were a short-lived group, largely because of disagreements around their collective purpose – was the group a forum for left-wing discussion or a political organisation capable of mobilising local activism? While this conflict was unresolved, Needle’s disruptive power was unquestionable. The magazine served as a hub for progressive, radical ideas in health, and its members passionately argued for a healthier future for all.

About the author

Leona Letts

Leona is a Senior Policy Officer at the NHS Race & Health Observatory, where she works to tackle ethnic inequalities in healthcare. She previously participated in the Wellcome graduate scheme and studied History at the University of Warwick. She is a Trustee of the social mobility charity Career Connect and volunteers with Sistah Space, a grassroots charity that supports Black women who have experienced domestic abuse.