Formal deaf education in Britain didn’t begin until the end of the 18th century. Historian Jaipreet Virdi describes how the first free school for deaf children came about.

The Asylum for the Support and Education of the Deaf and Dumb Children of the Poor was the first institution in England to offer free education to deaf children. It was a charitable venture that came about after 18-year-old John Creasy, who was deaf, and his mother attended a sermon at the Jamaica Row Church in Bermondsey, delivered by the charismatic and energetic Rev. John Townsend.

Mrs Creasy told the Reverend that her son had attended the private Academy for the Deaf, run by a Scottish teacher called Thomas Braidwood and she lamented the fact that most deaf children could not benefit from the same formal education as her son because of the cost. It was this conversation that inspired John Townsend to found the first free school for deaf children.

The private academy

Before the mid-18th century, deaf children in Britain had little to no access to formal education. Common opinion held that deaf individuals were incapable of language, thought, or learning. However, many families with deaf children did create their own ‘home signs’ for communication, and wealthy families sometimes challenged this view by hiring private tutors for their children.

In 1760 Edinburgh wine merchant Alexander Shirreff, enlisted Thomas Braidwood to educate his deaf son Charles. Braidwood devised a method to develop speech that broke down words into syllables. He used a silver rod upon the tongue to help articulation. He also incorporated signing with gestures and fingerspelling. The method proved remarkably successful for teaching, leading Braidwood to establish the Braidwood Academy in Edinburgh in 1769, the first private school for deaf children in the country. The ‘Braidwoodian method’ eventually laid the groundwork for what came to be known as the Combined System – the foundation of modern British Sign Language.

The manual alphabet used in the ‘Braidwoodian method’ was the forerunner to the modern British Sign Language alphabet.

Braidwood’s Academy served affluent families whose children needed formal education for inheritance, social status or public life. Graduates like Charles Shirreff (a portrait artist), John Goodricke (an astronomer elected to the Royal Society at 21), and Francis MacKenzie, the 6th Lord Seaforth (MP and governor of Barbados) demonstrated that deaf children (particularly boys) could achieve remarkable intellectual and professional success.

Access to such education came at a steep price. Ten years at the academy cost upwards of £1,500, roughly £240,000 in today’s money. The Braidwood family guarded their techniques closely, requiring prospective instructors to undergo lengthy internships and share profits. Despite occasional gestures toward charity, the academy remained exclusive to those who could pay.

A new charitable institution

Twenty years after Braidwood’s Academy, Rev. Townsend, spurred on by Mrs Creasy, set about creating a charitable institution that would provide a similar standard of education for the deaf poor but without the expense.

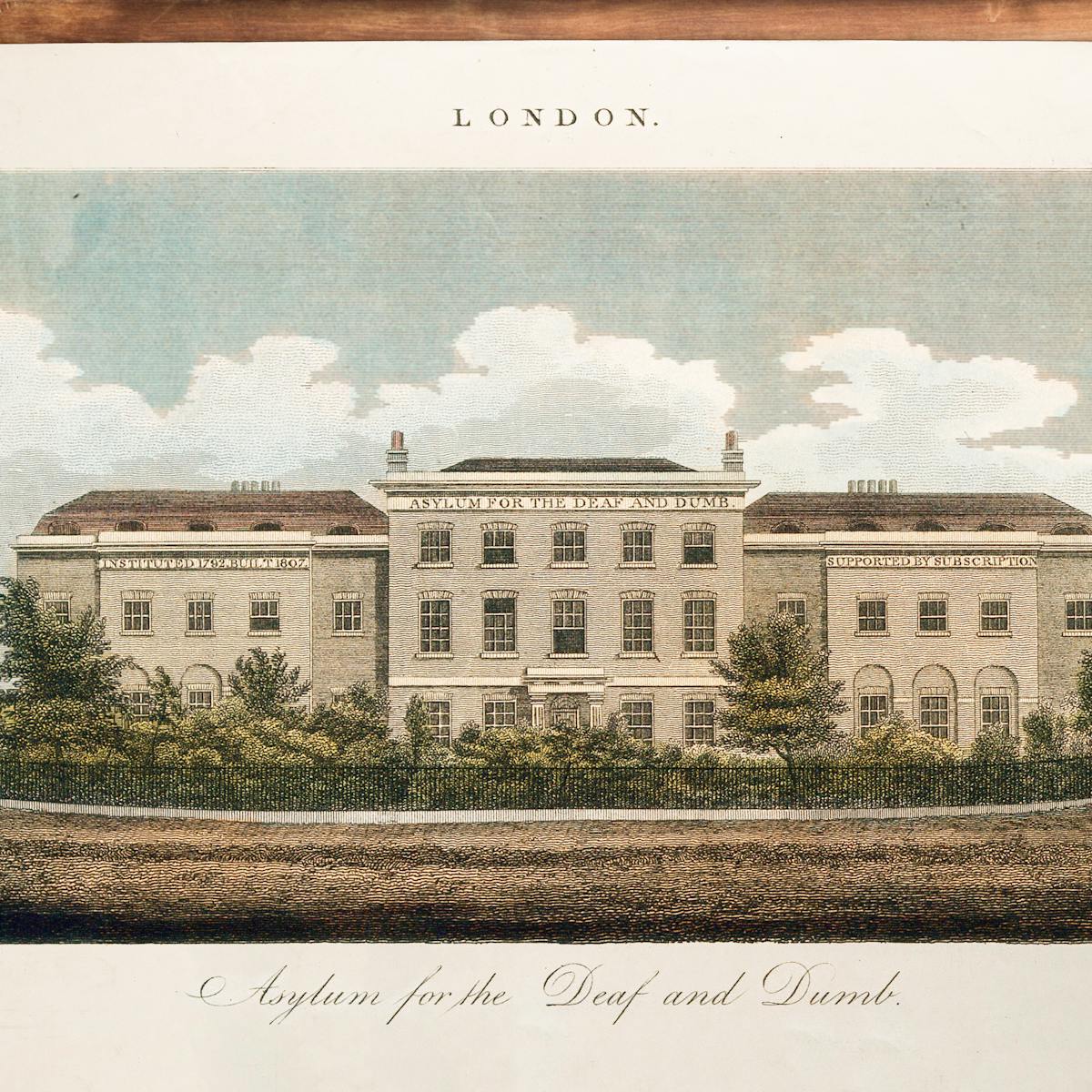

On 12 November 1792, the London Asylum for the Deaf and Dumb opened its doors at Grange Road in Bermondsey, southeast London. A combination of private philanthropy and public donations provided the students with clothing, food, teaching, vocational instruction and apprentice fees.

Braidwood’s nephew Joseph Watson, who was trained in the Braidwoodian method, was hired as headmaster and John Creasy was enlisted as a teacher.

Eligible children were aged between nine and fourteen and either born deaf or became deaf before learning to speak. They also had to be of “sound mind”, and thus capable of learning. An admissions committee met twice yearly to select new pupils. Families were expected to contribute towards school fees according to their means.

Reverand John Thomas, founder of the London Asylum, organised fund-raising and support for the charitable school.

Founded during a period of evangelical social reform, the London Asylum for the Deaf and Dumb was grounded in religious benevolence. For Townsend, the school’s mission was clear: to raise “so many forlorn, and helpless, and suffering beings, to feel a communion of interests, a participation of enjoyments, a power of becoming useful citizens”.

For many pupils, the Asylum offered an escape from overcrowded and deprived areas of London. Although its dormitories and classrooms were cramped and subject to outbreaks of illnesses like smallpox, the school was often safer than the homes they left behind and provided a community of other deaf children.

A growing demand for deaf education

As the school’s reputation spread, so too did the demand for places. By 1820, over 200 pupils were housed in the Asylum under the care of four hearing and eight deaf teachers. Larger premises were built on Old Kent Road to accommodate the growing population.

With limited places, the governors regularly rejected applications, leading desperate parents to press for admission for their child(ren). A petition for 10-year-old William Thompson, one of seven children was printed in the ‘Leeds Intelligencer’, pleading with the governors to accept him. William was finally accepted after repeated petitions from his father, a shoemaker.

The enlarged premises for the Asylum for the Deaf and Dumb on the [Old] Kent Road in Camberwell, London.

Children with perceived “intellectual deficiencies” were sent to the workhouses or asylums for the “feeble-minded”.

The Asylum governors – who voted on children’s admittance – also debated on how much classroom time could be spared before the pupils were sent to the manufactory for vocational training so that they could earn a living for themselves.

Life at the London Academy

Charity pupils often arrived at the school with their own rudimentary ‘home signs’ – used to communicate with their families, so classroom instruction included a mix of finger spelling and formal sign language to create a cohesive language among all students. One of the students, Sarah Smith, in her diary, makes several references to the common use of signs and finger spelling. In one entry, she “asked Martha Slater by the fingers if she could say her lesson of the meaning of verbs”. Yet, the Asylum’s speech training remained the ultimate goal, especially for the wealthier pupils, with the aim of creating a “distinct literate and well-to-do deaf class”.

Private pupils lived and studied under Watson’s supervision, while charity pupils divided their time between classroom learning and work in the vocational manufactory in training for roles in factory or domestic service.

A page from the vocabulary book used at the London Asylum familiarised pupils with different trades and prepared them for vocational work as part of their education.

The moral framework of charity demanded constant public justification for the existence of the school and governors and donors expected to see results. Like many institutions, annual reports and fundraising events became central to the Asylum’s operations.

Charity pupils were required to recite prayers or demonstrate their ability to sign or speak in front of visitors. While these acts may have helped to secure donations, they also reinforced the children’s status as objects of benevolence.

The children themselves actively contributed to the success of the school and hence secured their own safety and education. Sarah Smith acknowledged her situation as a pupil in such a unique school, reflecting in her diary: “I think when people see this house, they want to come and see the children in this school.”

Sign language versus speech training

By the 1850s, the Asylum began to engage with medical professionals, reflecting a greater cultural shift towards oralism – the belief that deaf children should be taught to speak and lip-read, not sign. Though charity pupils continued to receive less speech training than their private counterparts, by this period all pupils were required to learn to speak "artificially", although this practice was often ineffective and confusing for those fluent in sign language.

Watson remained committed to the combined method of articulation and signing, believing that speech training helped charity pupils to secure employment after graduation. Eventually this method would fade to be replaced by oralism in deaf schools with the goal of assimilating deaf people into ‘normal’ society.

John Watson, first headmaster of the London Asylum developed and shared the Braidwoodian method in his book, encouraging deaf education to spread.

Following Thomas Braidwood’s death in 1806, Joseph Watson, who had been bound by secrecy from revealing the Braidwoodian method, published his book ‘Instructions for the deaf and dumb(view in catalogue)’, encouraging educators across the country to implement the method in their own institutions and make deaf education more widely available. The success of the London Asylum led to similar institutions being established in several British cities throughout the 19th century, marking the transition of deaf education from private privilege to public benevolence.

In its early decades, the London Asylum crucially transformed public perceptions of deafness by proving that deaf children could learn, work and thrive. Yet it also reflected the problems with a charity model built on moral obligation and public scrutiny. The Asylum empowered students through education but only within the confines of wider class divisions. A reminder that even well-intentioned systems can reproduce inequality when access is limited and dependent on goodwill alone.

About the author

Jaipreet Virdi

Dr Jaipreet Virdi is a historian of medicine and disability based at the University of Delaware. Her first book, ‘Hearing Happiness: Deafness Cures in History’ is available where books are sold. She is currently working on her next book, ‘An Invisible Epidemic: The History of Endometriosis’.