Historically, prostitution has been punished, sometimes tolerated and only rarely accepted in society. The stories around sex work have been told mostly by researchers, artists and other academics. But today, mapping the different ways in which sex work has been perceived helps us to understand, and to look beyond stigma.

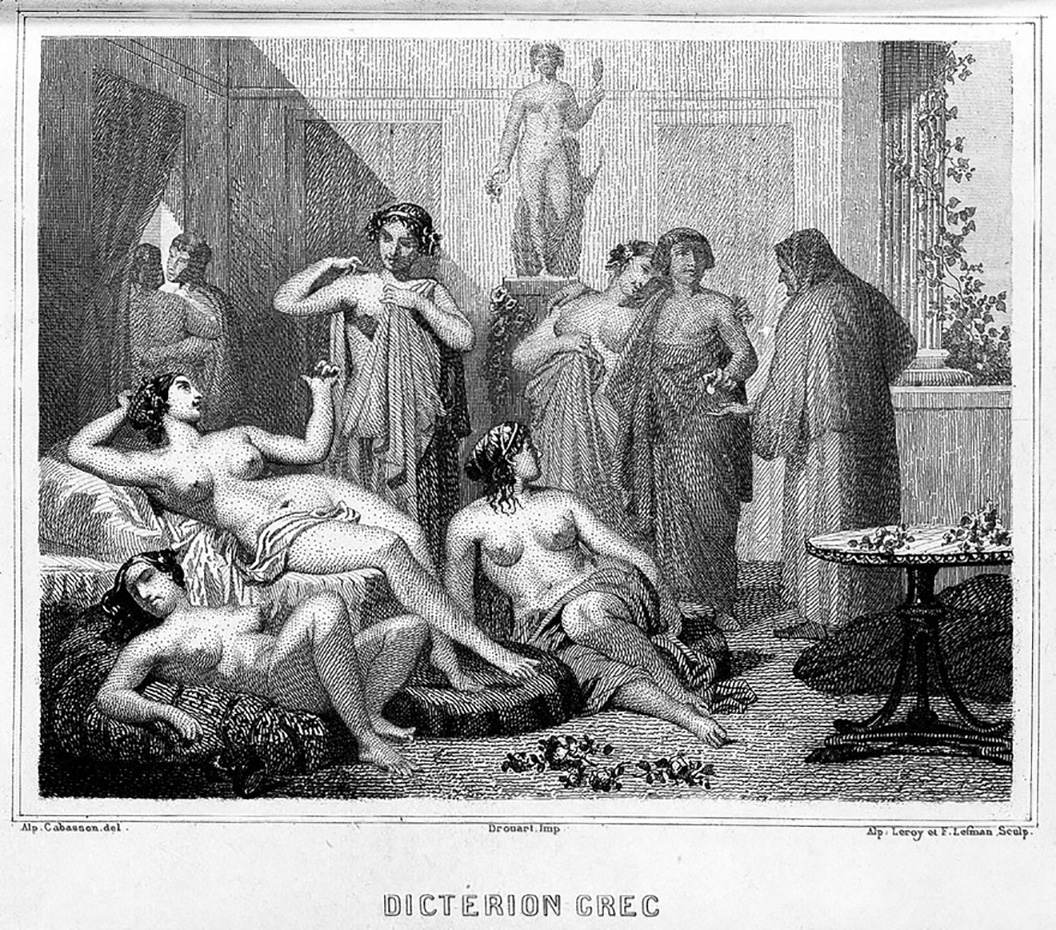

In Greece and Rome, brothels were established institutions, but sex work was often performed by slaves. These women were called pornai or ‘free women’. However, the adjective ‘free’ wasn’t really related to their social status, since these individuals were not allowed to get married or take part in public ceremonies. The very first public brothels in Greece had a precise social function: to prevent homosexuality between young men. These houses were often marked with a red phallic painting on the door and illuminated with a lamp, giving rise to the term ‘red light’ district today.

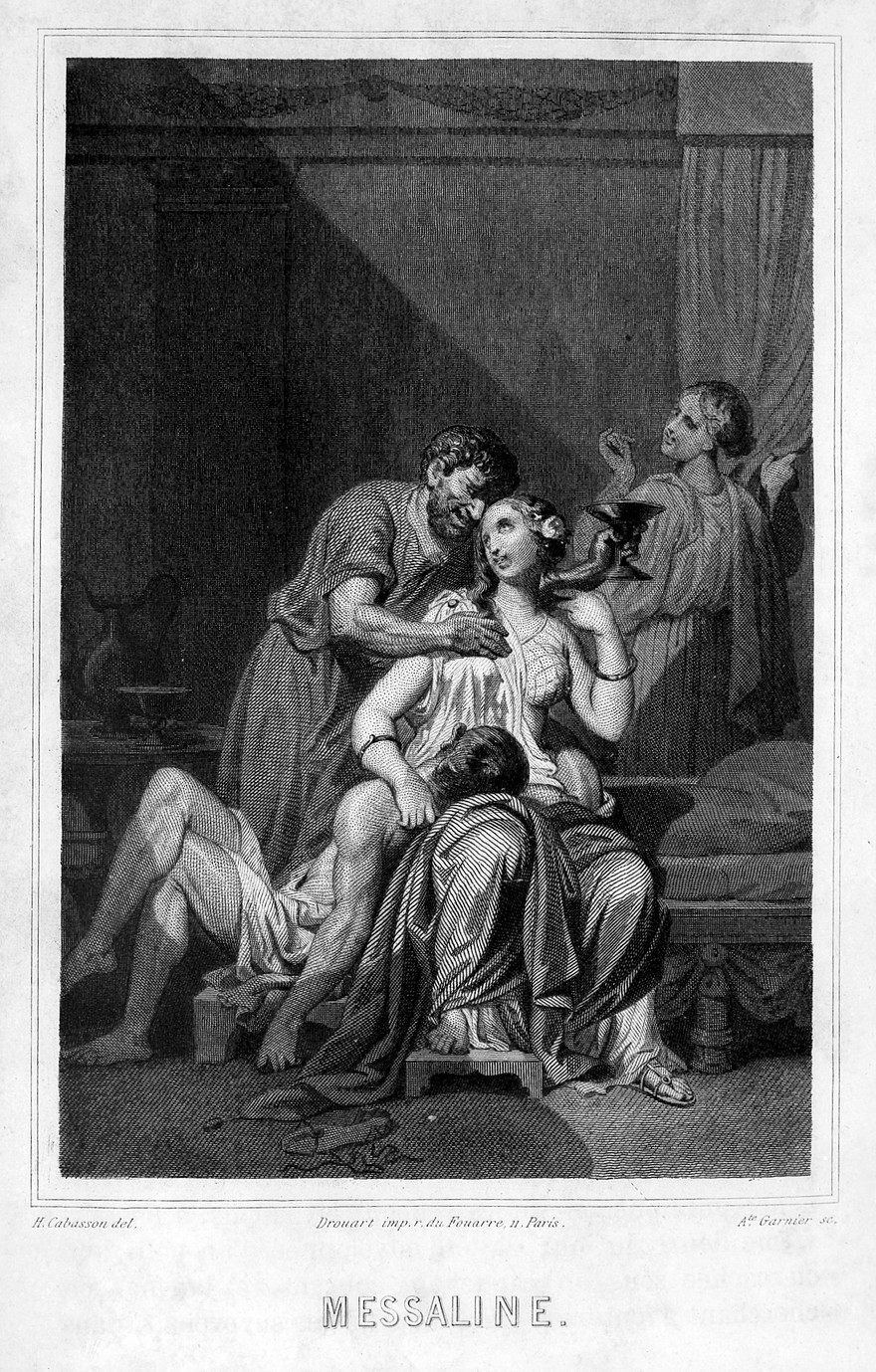

Women of the aristocracy were sometimes attracted to brothels, not for money but for pure enjoyment, the most famous being undoubtedly Valeria Messalina, third wife of the Roman emperor Claudius. It is said that when evening fell, the beautiful Messalina ran at great speed to the lupanare (brothel), where she enjoyed herself in the trade, adopting the name of Licisca. According to a story by Pliny the Elder, she once challenged the most famous sex worker of the time to a race and won, having 25 intimate encounters in one night.

The word ‘brothel’ comes from the old French bordel, a variation of the word borde (small house or hut), but is also connected to the fact that in French cities the brothel quarter was always located on the banks of the river (bord de l'eau – at the border of the water). Historically, brothels have been considered places of chaos, where violence wasn’t unusual. This may also explain why the term bordello in Italian also means noise or mess.

Mary Magdalen is undoubtedly one of the most powerful women mentioned in the Bible. While much has been said about her, very little is known about this influential woman. It has been suggested that she was a disciple of Jesus, or even his wife, or perhaps a courtesan/prostitute. This last is supported by representations showing her with long, curly hair (more respectable women of the era would have had their heads covered) and wearing yellow, a colour traditionally symbolising shame and madness.

Most religions have traditionally frowned on sex as a form of pleasure, promoting the act as sacred and reserved for reproduction. Despite ‘sacred prostitution’, sexual intercourse as a fertility rite, performed as part of religious worship, “the contest between the spirit and the flesh” is still a loud contemporary discourse. In 2019 the book ‘Donne crocifisse’ by Priest Aldo Buonaiuto, with a preface written by Pope Francis, describes prostitution as “a disease” of humanity.

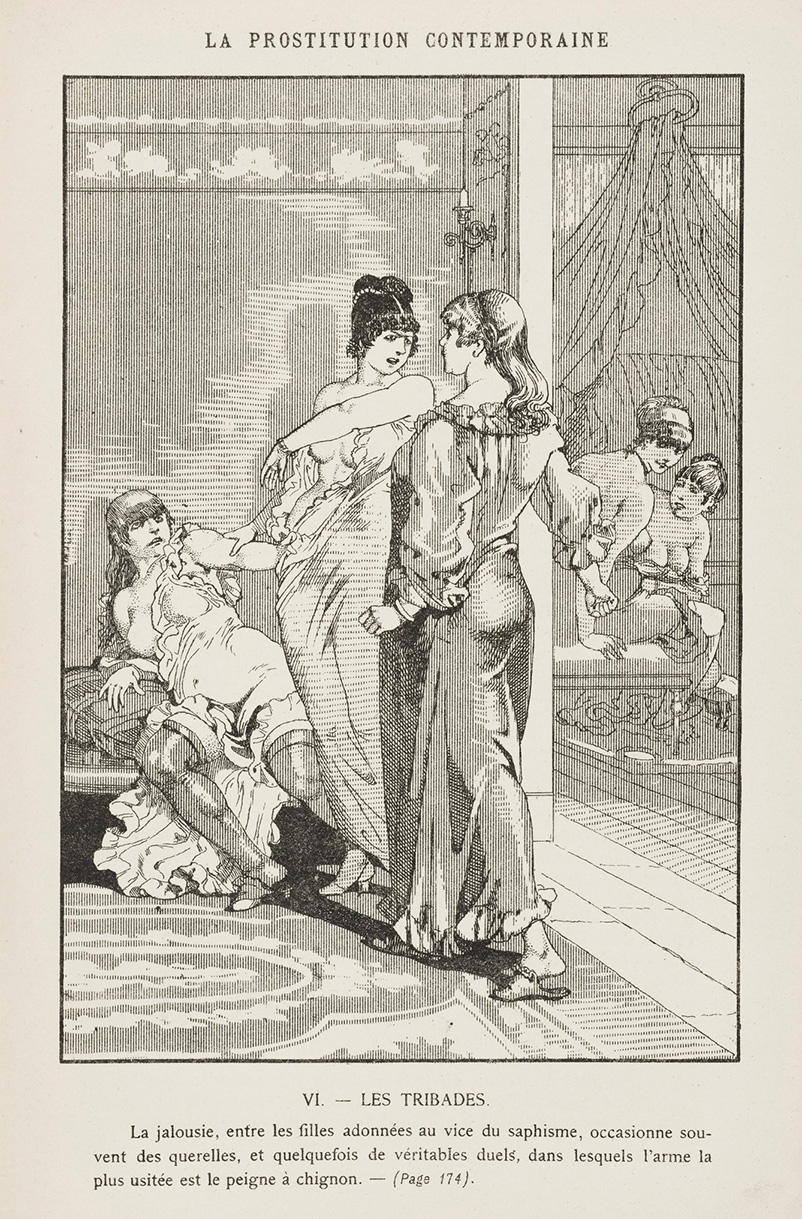

Male sex workers are commonly seen as engaging in sex work out of their own free will and for enjoyment, while female sex workers are often perceived as victims. The 1889 Cleveland Street scandal saw numerous aristocrats identified as attending a male brothel in Fitzrovia (London). At a time when sex between men was a crime in England, the scandal encouraged the attitude that homosexuality corrupted young people of the lower classes.

Since its arrival in Europe at the end of the fifteenth century, syphilis has been mainly associated with prostitution and its horrific symptoms interpreted as a Divine punishment for promiscuity. The belief that women were the main carriers of the disease is the reason that syphilis is often personified as a woman in sexual health adverts, with men being the victims in danger. Women selling sexual services were demonised, obliged to pay a tax, banned from cities and isolated in specialised hospitals.

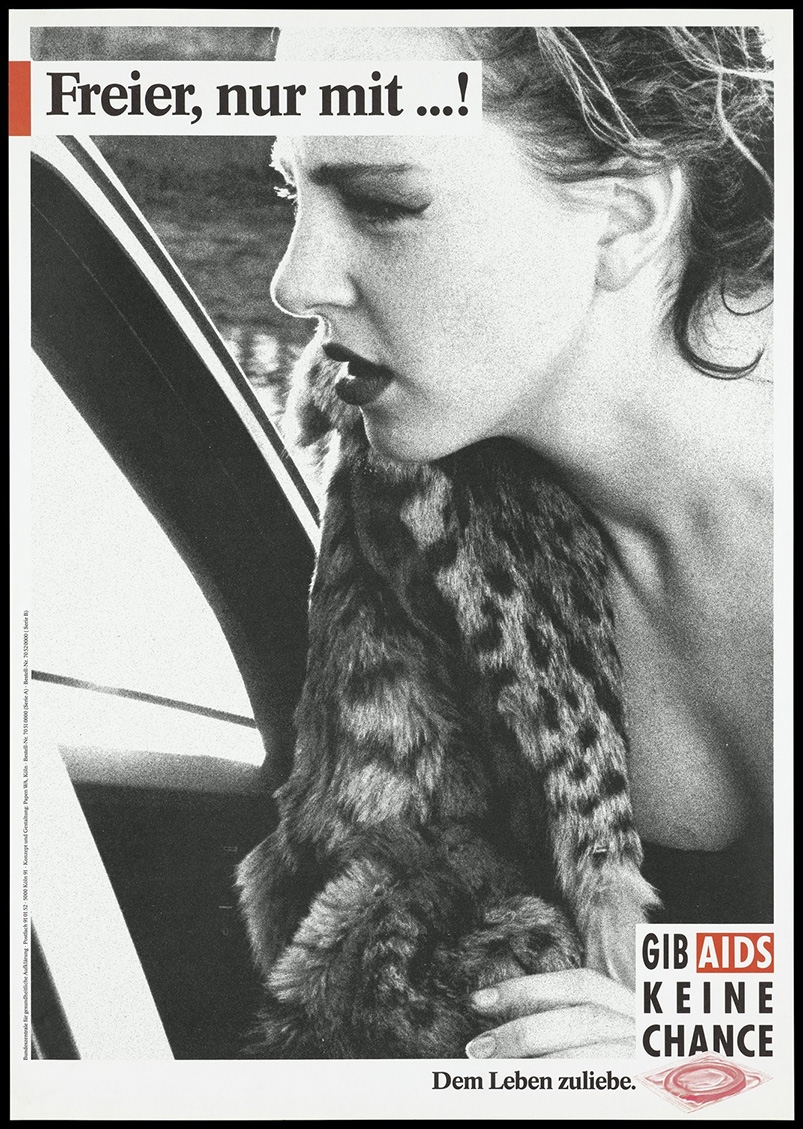

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s sex workers were often the central focus of AIDS and safe-sex campaigns. Empowerment and decriminalisation of sex work through legislative reforms and government funding of sex workers’ organisations has been the main aim of the German Aidshilfe campaign, “freedom of choice”. The campaign reinforces the importance of using condoms as well as the need to give sex workers appropriate healthcare.

Tart cards, as they were colloquially known, were used to advertise the services provided by sex workers. Placed in telephone boxes or dropped in the streets, they were not simply advertisements, but wonderful examples of self-representation, allowing historians to chart the sexual services fluctuating in the industry and eventually revealing the migration of sex workers in towns and cities.

Self-representation continues in Sex Worker’s Opera, a collective of sex workers and friends. Based on the experiences of its members – from escorts, strippers and brothel workers to webcam models and underground migrant workers – the award-winning show breaks stigma and stereotypes through arias, jazz, hip-hop, spoken word, sound art, projections and poetry.

About the author

Agnese Reginaldo

Agnese Reginaldo is an art historian whose work focuses on the intersection between art and social sciences. Her practice focuses on public-engagement projects aiming to create a more effective connection between the public and contemporary art in museum and gallery settings.