The great generator of confusion, rumours have not spared human health from their chaos. These images from our collection reveal how false information has materialised in print and publication and spread misinformation. From alleged plague-carriers and quacks to superstitions about immunisation and the first ever anti-vaxxers, this topic has a rich visual history.

Superstition, contagion and medical rumour

Words by Sarah Meillon

- In pictures

The word ‘gossip’ was originally contracted from “god-sibling”, the term used for the godparent at baptism. In time, the word was extended in usage and applied to any close friend, and, more frequently, for a woman’s closest friends that assisted at the delivery of her baby. However, for royal women childbirth was no private event. A horde of spectators were necessary to prove to the court that the baby was from the royal woman’s womb and not a changeling swapped in a bed warming pan.

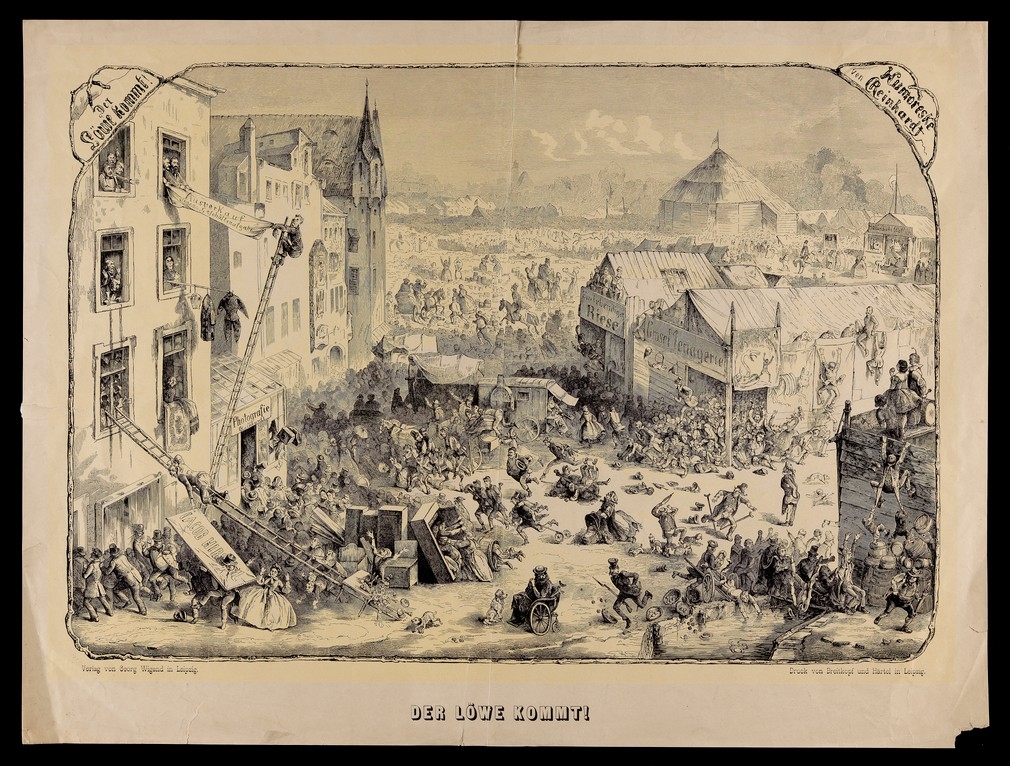

This 1860 German lithograph is entitled ‘The Lion is Coming’ and illustrates the chaos caused by rumours. In this case, the rumour that a lion escaped from the local zoo or circus has caused mass panic. In the 19th century, it was argued that panic itself could be the cause for the propagation of diseases .

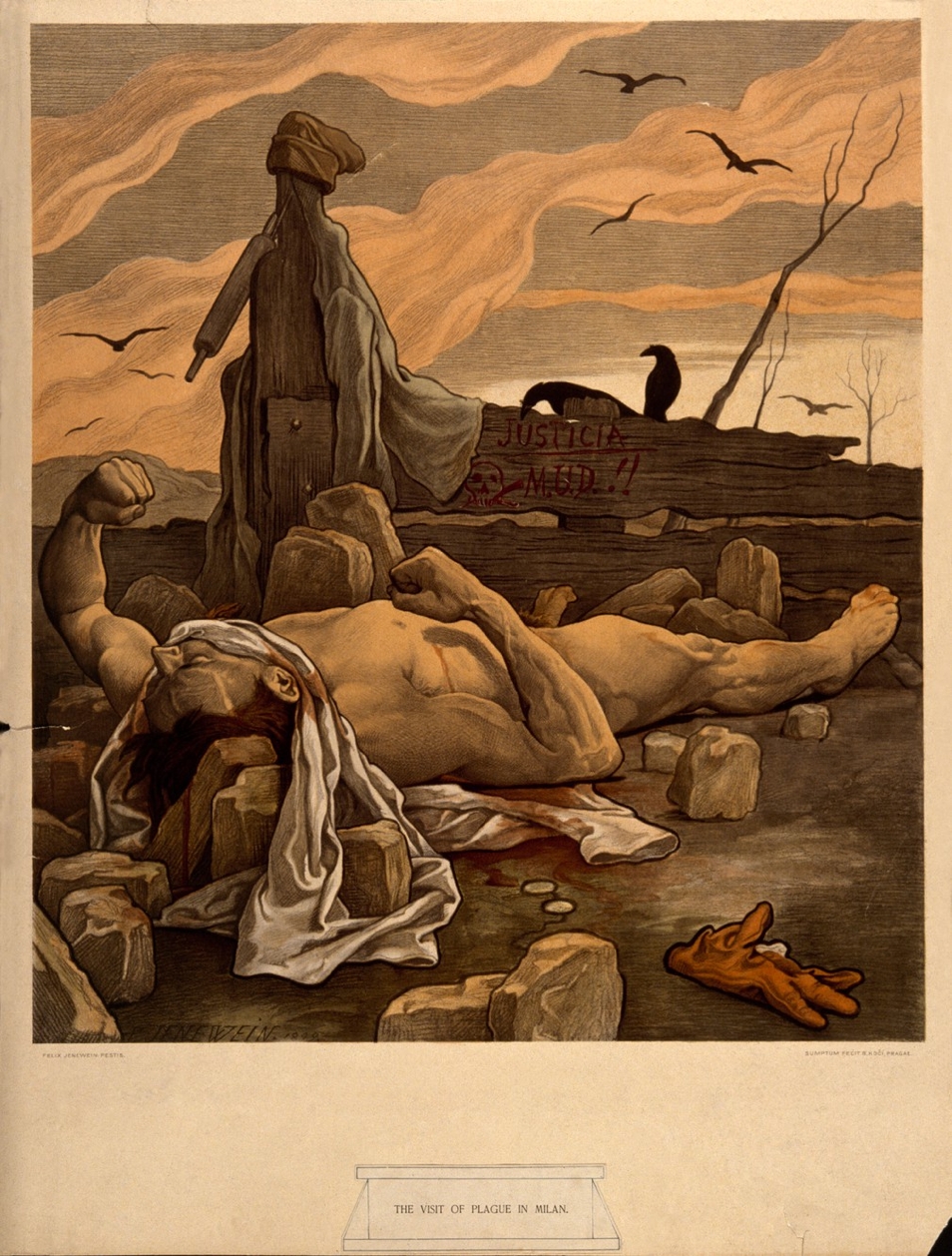

Epidemics can be a breeding ground for uncertainty and the proliferation of mass panic. Historian Karel B Mádl commented on this print: “Men... in their frenzy seize anyone, whom they suspect of spreading the poison, and who is unable to afford them help. The Black Death used to be followed by bloodshed. Here lies one victim of it.”

Having blind faith in physicians is no new phenomena. In this mezzotint from 1772, to prove his faith in his physician, Alexander the Great is seen swallowing his physician’s draught despite allegations that the contents were poisonous.

This satirical print from 1832 illustrates the contemporary belief that miasmas, or ‘odours’ caused disease. The man wears a ‘cholera preventive costume’, which involves carrying a range of ‘protective’ odorous equipment, from acacia trees to perfumed teas. The caption warns: “By exactly following these instructions you may be certain that the cholera… will attack you first.”

Satirical imagery was an outlet for expressing mistrust in physicians and criticisms of the medical authority before the post-truth era of fake news and social media. This print from 1826 warns people against blind faith in doctors. Here, a juror informs the coroner that the alleged deceased is in fact still alive, to which the coroner answers that, since the doctor already proclaimed him dead, “he must remain dead.”

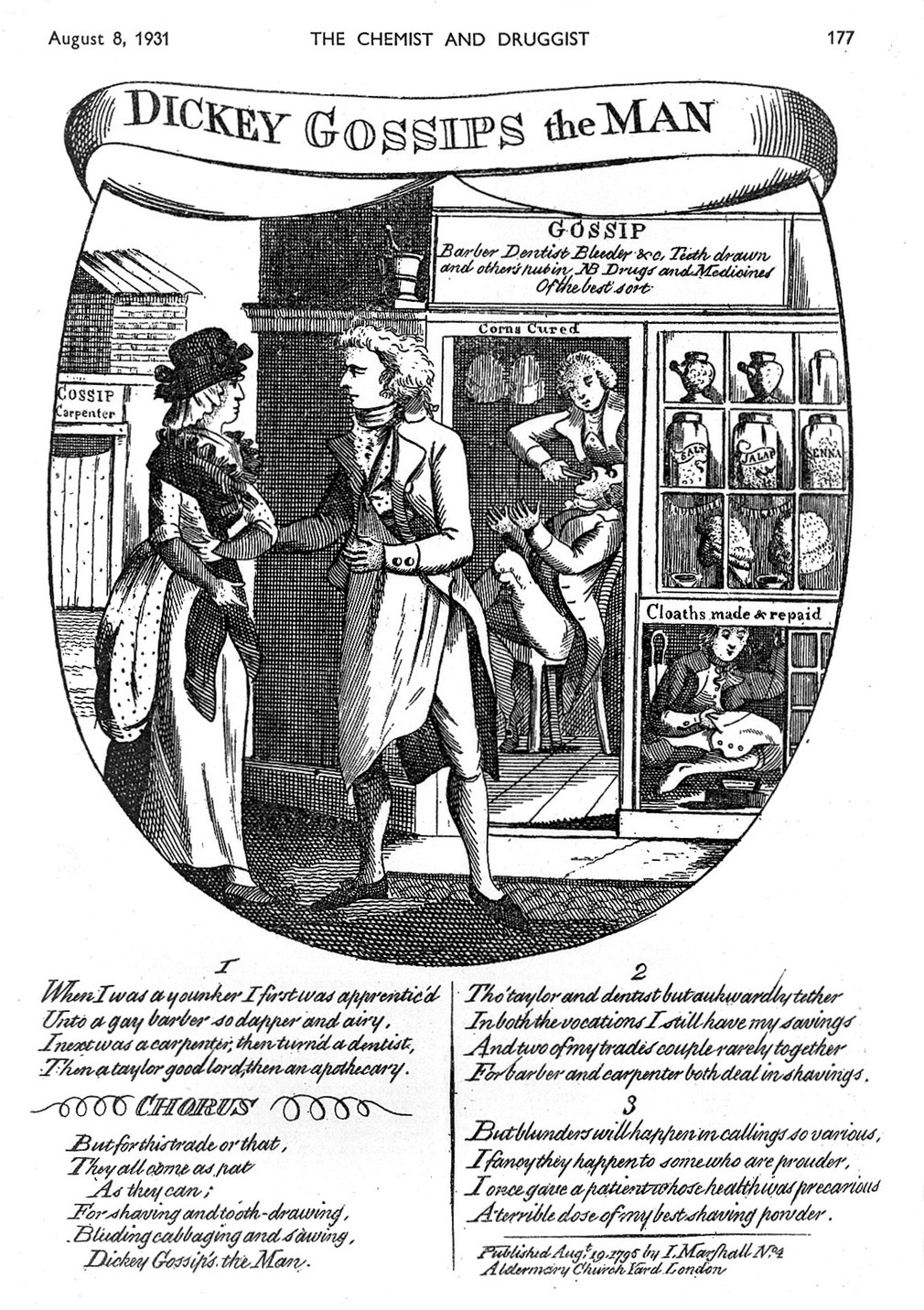

A quack doctor dupes his customers into believing his credentials and the ‘remedies’ he sells. The ‘Gossip’ sign on the façade of the establishment suggests his products are only rumoured to work. The song at the bottom of the print confirms this: “I once gave a patient whose health was precarious a terrible dose of my best shaving powder”.

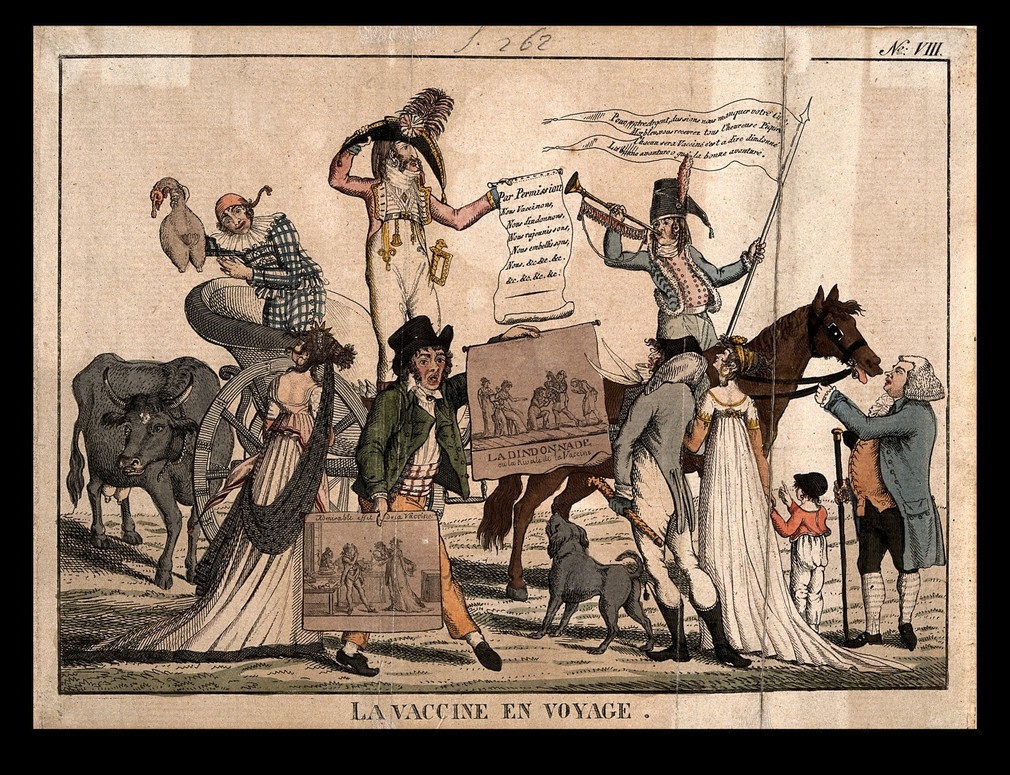

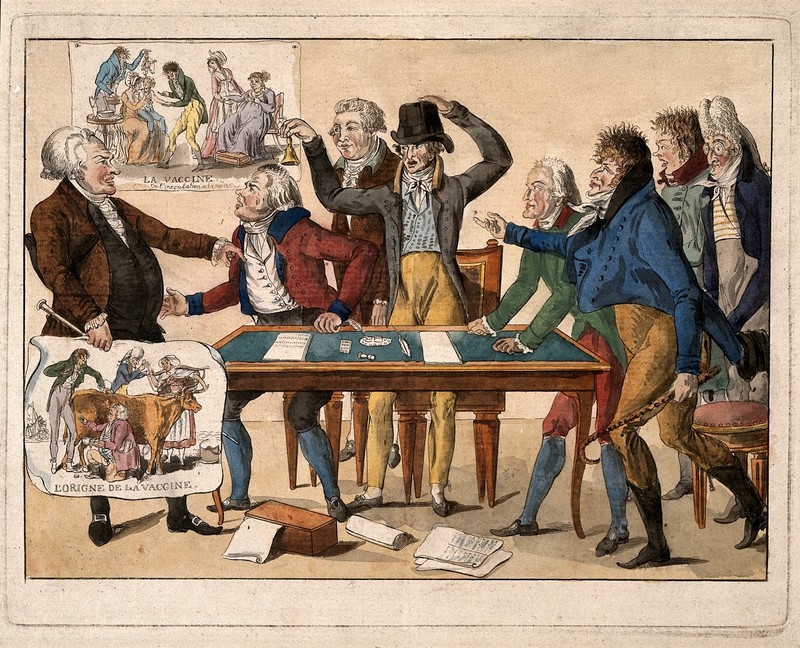

Following the development of the smallpox vaccine in 1796, rumours spread through 19th century France that the vaccine was an expensive form of British quackery. This satirical print shows a procession of health workers promoting the vaccine. They carry a poster on which the word ‘dindonnade’ is written, which relates to both the French word for turkey (dindon) and to dupe. The Depeuille publishing house published many similar satirical prints which reflect general wariness surrounding vaccination.

Countering rumours has always been a challenge. In this illustration, seven members of the French committee on vaccination are shown shouting at a health officer. The health officer maintains that vaccines are “une pure charlatanerie”, in other words, quackery in its purest form. This etching shows him defending himself from the committee members by holding in front of them a print from the Depeuille publishing house, while another one is hung on the wall in the background.

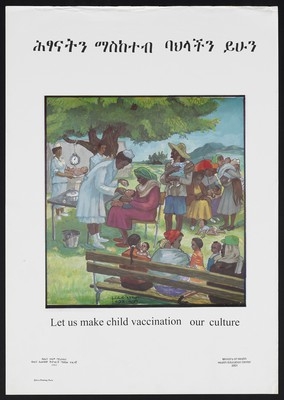

This poster was released by the Ethiopian Ministry of Health in 1993 to combat societal opposition to vaccination. It urges for child vaccination to become integrated into Ethiopian culture. In 2018, the Wellcome Global Monitor report revealed that 79 per cent of people believe that vaccines are safe and 84 per cent agree that they are effective.

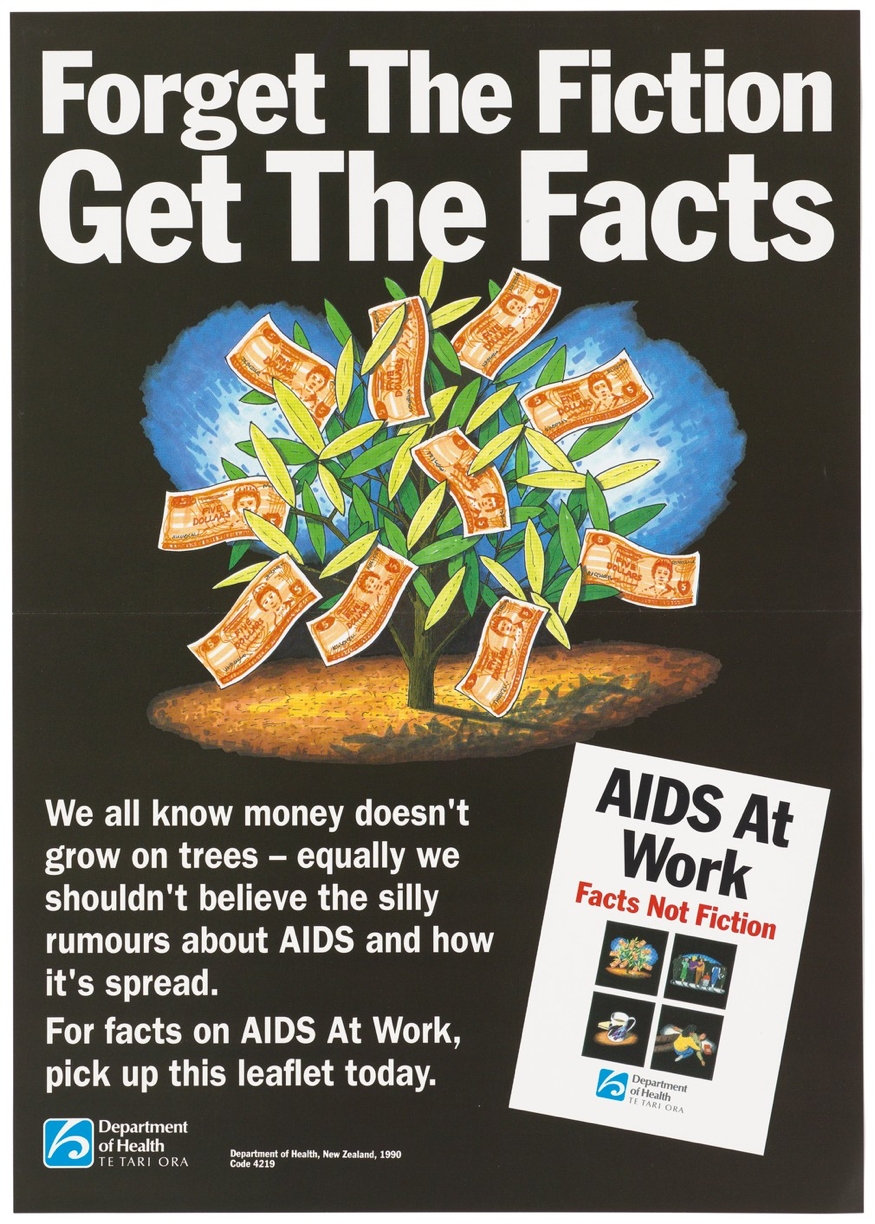

In the 1980s the AIDS crisis served as a hotbed for medical misinformation owing to lack of knowledge surrounding the virus and its modes of transmission. Posters attempted to better inform people about the disease by directly addressing these rumours.

About the author

Sarah Meillon

Sarah is a Research Development intern at the Wellcome Trust. She studies Social Anthropology at LSE. Her interests include ethics of care and welfare, narratives of illness, and community medicine.