On 5 July 2018, Britain’s National Health Service celebrated the 70th anniversary of its founding. Discover how an abstract ideal was made reality by the determination of a postwar Labour government.

The birth of Britain's National Health Service

Cal Flynaverage reading time 7 minutes

- Serial

Over the past seven decades the NHS has weathered two monarchs, 15 prime ministers, 29 health secretaries, countless changes in policy, and controversies and crises of all kinds – during which time it has come to occupy a unique position in national culture and identity.

It is more popular than any other British institution – more so than the royal family, the armed forces or the BBC – and for the grand majority of those now living, the NHS has been a constant presence throughout their lives. It has assisted in their birth, nursed them through ill health and will tend them on their deathbed.

Formation of the NHS

The NHS as we know it today grew out of a government report composed during the darkest days of World War II. Written by the economist Sir William Beveridge, this 1942 report reimagined the role of the state in a postwar nation, setting out to combat the five “great evils” of society: want, disease, ignorance, squalor and idleness.

“A revolutionary moment in the world's history is a time for revolutions, not for patching,” wrote Beveridge. To a country ravaged by war – a “bankrupt nation”, in Winston Churchill’s words – it was a bold and distant vision of a better future.

Healthcare before the NHS

In 1945, shortly after the war in Europe had drawn to a close, Clement Attlee led the Labour Party to a shock landslide victory over Churchill’s Conservatives, and set about transforming Beveridge’s vision of a welfare state into reality. A major component of this was the creation of a universal health service, available to all and for free. Aneurin Bevan, a prominent socialist and the son of a miner, was tasked with spearheading its creation.

Up until this point, healthcare had consisted of an uneven patchwork of services that varied widely by region.

‘Voluntary’ hospitals, aimed at the ‘sick poor’, provided the bulk of emergency care and relied largely on charity. They were staffed by physicians and surgeons who donated their time and expertise while making a living from their private practice. Municipal hospitals, a vestige of the old workhouse hospitals created under the Poor Laws, were run by local authorities.

Upper- and middle-class patients were barred from these public wards on the basis that it was an abuse of charity, and expected to pay. In return they received greater privacy and a higher standard of care. Some hospitals ran more successfully than others, but by the 1930s hospitals across the country were facing financial crisis and growing waiting lists.

The cover of A J Cronin’s book The Citadel, which contrasted private Harley Street medical practices with the socialised system in the mining town of Tredegar.

A hunger for change

Public hunger for change was building. Back in 1937, the bestselling novel The Citadel had presented a searing indictment of prewar health provision, based on the author A J Cronin’s experiences as a doctor in London and the mining villages of south Wales. In it, he contrasted the corrupt, immoral private practices of Harley Street with a socialised system he had worked for in Tredegar, Blaenau Gwent. The book’s enormous success has been credited with laying the groundwork for a universal health system in popular opinion.

There were other cases from across the country that gave some indication as to how a national health service might function. In Scotland, an ambitious state-funded health service had served the dispersed, rural population of the Highlands and Islands since 1913. Then, during World War II, the government had taken unprecedented control of hospitals under the Emergency Medical Service in anticipation of tens of thousands of air-raid casualties. Both systems demonstrated how much could be achieved when health services were centrally administered.

For Aneurin Bevan, however, the inspiration would come from closer to home.

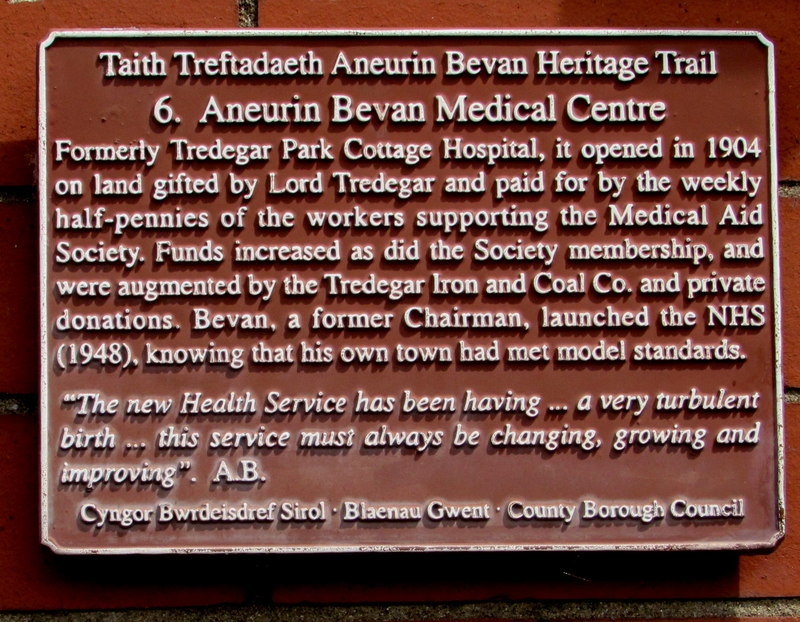

A plaque commemorating the Tredegar healthcare system and the National Health Service it inspired.

Aneurin Bevan and the NHS

Bevan himself was born in Tredegar, and was intimately aware both of the efforts his local community had made to preserve themselves in ill health, and the danger of going without adequate care. One of ten siblings, of whom only six had survived into adulthood. he had also lost his father to pneumoconiosis (‘miner’s lung’) in 1925.

The Tredegar Workmen’s Medical Aid Society, where Cronin had worked and where Bevan’s father had been treated, had been formed in 1890 by a merger of local benevolent societies. It was intended to provide medical benefits and funeral expenses to miners, steelworkers and their families – and later the whole community. Members made weekly financial contributions, which collectively enabled them to employ doctors, a surgeon, and to maintain a hospital.

This would become Bevan’s model as he worked on the National Health Service project. As he would explain to the country in 1948: “All I am doing is extending to the entire population of Britain the benefits we had in Tredegar for a generation or more. We are going to Tredegarise you.”

Around this time Bevan made clear the key principles that underpinned this new service: it must “universalise the best”, not simply provide a safety net for the poorest; it must be “free at the point of delivery” – that is, the patient does not pay at the time of treatment; and it must be provided according to need, not the ability to pay.

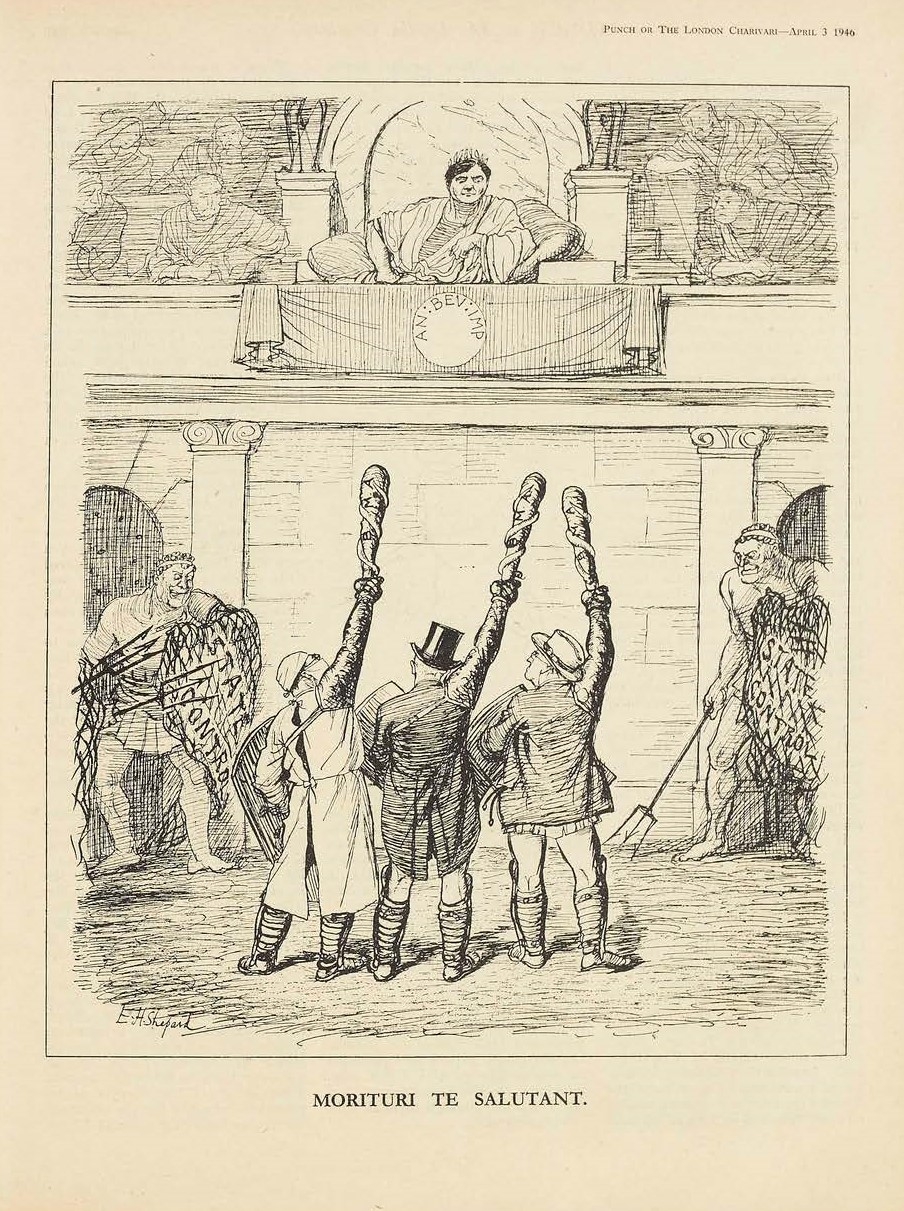

A Punch cartoon illustrating the doctors' defeat by Bevan.

Opposition to the NHS

Bevan faced a big job. Not only was a huge proportion of the country’s hospital stock war damaged, but many doctors were still in army service. Of those who remained, a large proportion was still to be convinced. Many of them had established practices and were resistant to change.

Between 1945 and the launch of the NHS, Bevan engaged in furious battle with the British Medical Association (BMA), the doctors’ union, over the terms of service offered to doctors – specifically the issue of whether they should be directly employed on set salaries.

In 1947, the BMA threatened to boycott the new service and the row became increasingly public: one letter in the British Medical Journal described Bevan as “a complete and uncontrolled dictator” and cooperative doctors as “quislings” (after the head of the puppet government in Nazi-occupied Norway). For his part, Bevan accused the BMA of engaging in “a squalid political conspiracy” and “organising sabotage of an Act of Parliament”.

Finally a deal was brokered in which GPs would retain the power to run their practices as small businesses, and consultants could both work for the service and retain their private patients. As Bevan put it bluntly, he “stuffed their mouths with gold”.

Introducing the National Health Service

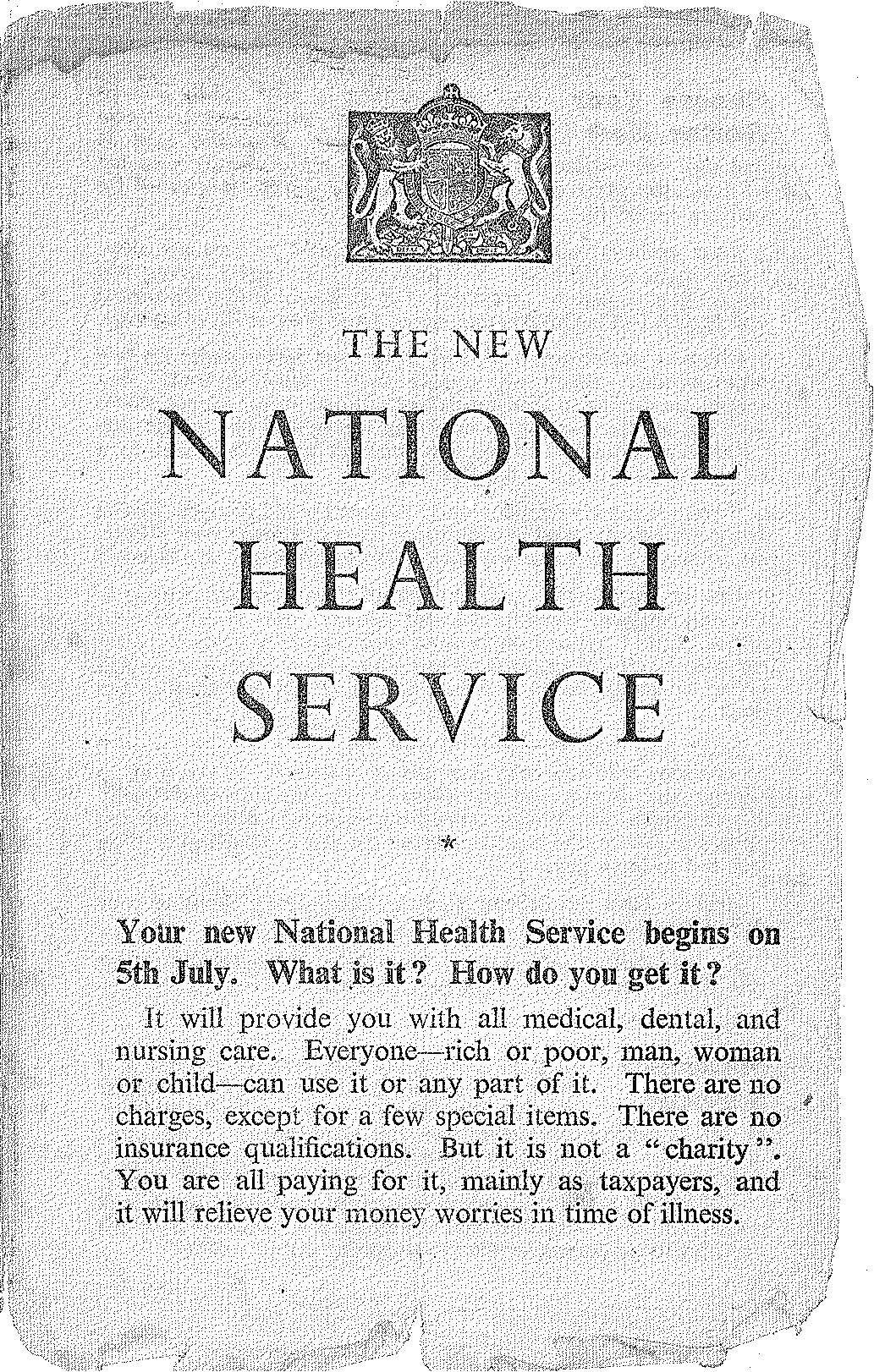

Pamphlets explained the workings of the new National Health Service and answered questions such as "What is it? How do you get it?"

Leaflets were produced for different areas – this one advises how the NHS would work in Scotland.

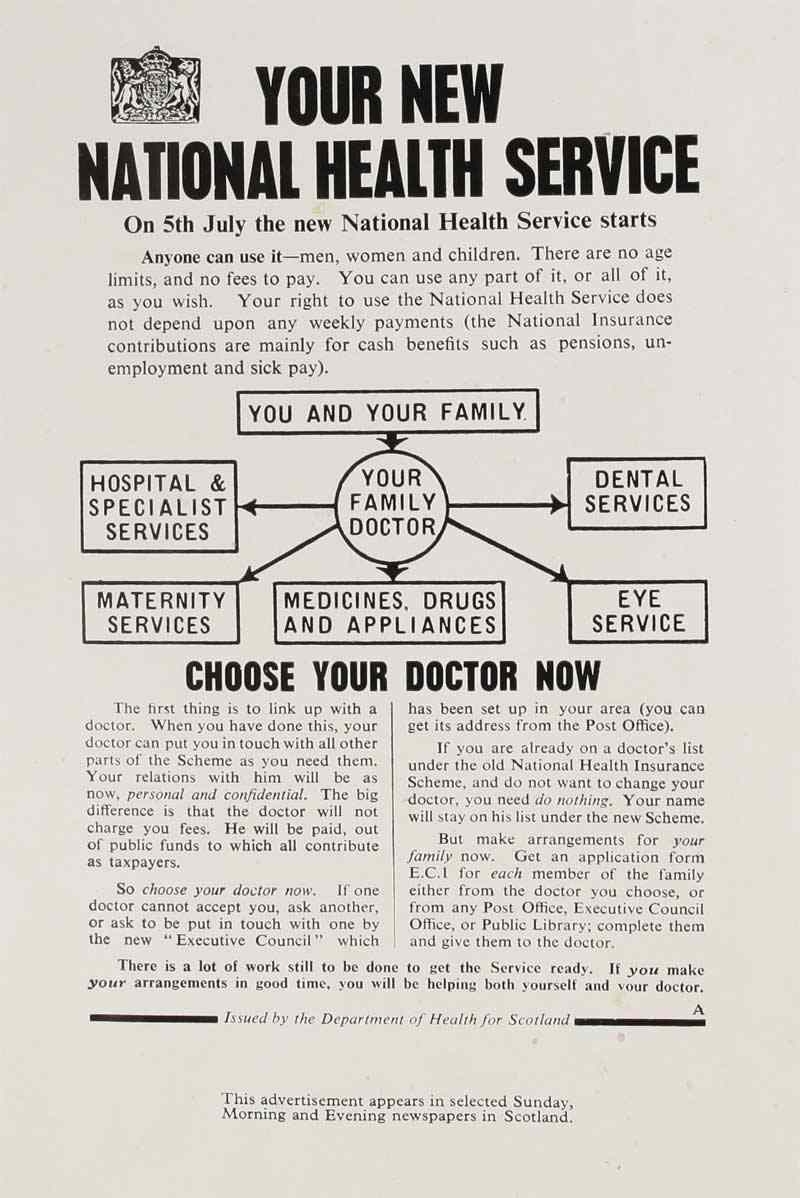

The new NHS was explained through diagrams such as this one, advising patients to "choose your doctor now".

The “appointed day”

Britain’s National Health Service came into existence on 5 July 1948. It was the first universal health system to be available to all and financed from taxation. It was also, Bevan admitted, “the biggest single experiment in social service that the world has ever seen”.

Ethel Armstrong, now aged 88, was then a student of radiology at the Royal Victoria Infirmary in Newcastle. “It was just unbelievable. You couldn’t believe that whatever it was that you needed, that required medical attention, was going to be given to you totally free of charge. Before then, it was very much a two-tier system. If your parents had money, you could pay for care. Large families were struggling… Today we take everything for granted.”

Ethel had a high-flying career in radiodiagnosis and radiotherapy, retiring in 1990 only to immediately join the NHS Retirement Fellowship, a charity that supports retired NHS workers – “the small cogs which turn the big wheel that is our NHS”. She is now a life patron. In March she was awarded a MBE recognising 70 years’ service that have spanned the length of the health service itself. “My passion, enthusiasm and commitment to the NHS have never waned,” she says.

Faces of the NHS: 1940s

Ethel Armstrong recalls her interview to go and work for the NHS: "I walked through the oak-panelled doors with Queen Victoria's portrait standing at the front, with my shiny shoes and half a crown in my pocket. Until then, I had never, ever, walked through the door of any hospital... because it was not a free service until 5 July 1948, so you had to pay for your care, so I did not know what to expect."

Peter Tonks first began work as a hospital clerk in 1946, before the NHS. He remembers, "When I went for the interview... there were two patients scrubbing the floor on hands and knees." Under the NHS, he said, "We realised that we could improve the environment for the benefit of the patients." One of the improvements Peter made was to introduce paid domestic staff.

Joyce Thompson was training as a nurse when the NHS was created. Joyce said, "I decided to go into nursing, I feel, through my father, who was a big St John's Ambulance man. When I was little, there was no such thing as the NHS, and there were doctors' bills to pay... there was always knocking at our front door for father to look at cuts... he did a lot of that kind of work and I always went to the door behind him to see what was happening."

Ethel is not alone in her strong feelings for the NHS. Historian Jenny Crane from the People's History of the NHS project observes that: “Over the late 20th century, members of the public, campaign groups, and politicians alike have positioned the NHS as fundamentally entwined with and imbued by 'British values'.”

By one means or another, the NHS cares for us in sickness and in health, from the cradle to the grave, in the home, clinic and hospital.

About the contributors

Cal Flyn

Cal Flyn is a writer and reporter from the Highlands of Scotland. She writes across the British press, including the Guardian, the Sunday Times, the Daily Telegraph, Prospect and New Statesman. Her first book, ‘Thicker Than Water’, was published by William Collins in 2016, and selected by the Times as one of the best books of that year.