An 18th-century trade card reveals a lot more than its owner might have intended.

The chymist’s trade card

Words and poetry by Julia Nurseaverage reading time 4 minutes

- Serial

Imagine entering the shop of chymist (the word ‘chemist’ was not used until 1790) Richard Siddall, as it appears on his trade card from around 1750. If the representation is at all accurate, it must have been an enticing experience, with its stuffed specimens hanging from the ceiling, mysterious potions cooking in a furnace and shelves lined with jars of exotic substances. Regardless of the authenticity of the depiction, unravelling its rich imagery reveals a lot about the origins of pharmacy.

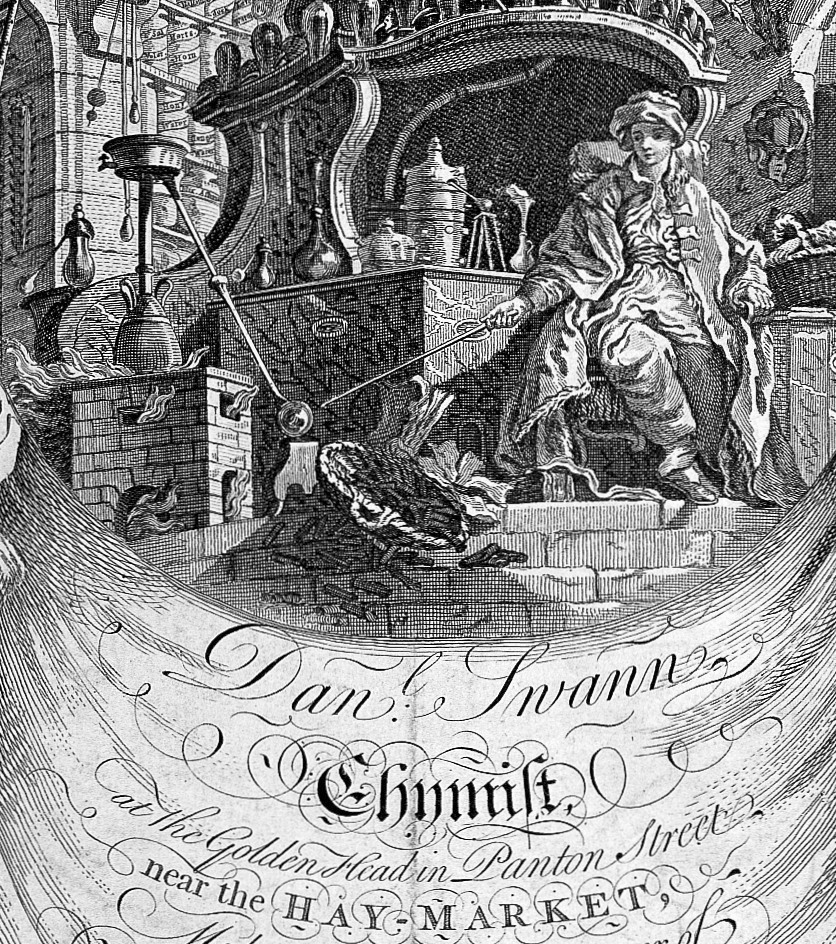

Thanks to the burgeoning 18th-century print industry, traders like Siddall no longer had to rely on their street signs to attract customers. Small, portable graphic prints promoted their wares well beyond the high street. There are many examples of Siddall’s card in historic collections today, proof that it was widely distributed – and kept! Siddall passed his business and brand over to a Daniel Swann who, seeing no reason to change a good thing, simply replaced Siddall’s name with his own and continued using the same design for another 20 years.

Looking at the card more closely, rococo decorative flourishes dominate. This fashionable graphic style, characteristic of the 18th century, was first introduced by the French type founder Pierre-Simon Fournier (1712–68). He pioneered not just the ‘type family’, a series of typefaces of the same design but with differing stroke weights, but also a wide range of decorative ornaments and florid fonts. The architectural features and swathes of the fringed curtain on the card, as well as the varying fonts, were all inspired by Fournier’s designs.

Rococo graphics

A close-up of Daniel Swann’s trade card, which was identical to Richard Siddall’s in every detail except the name.

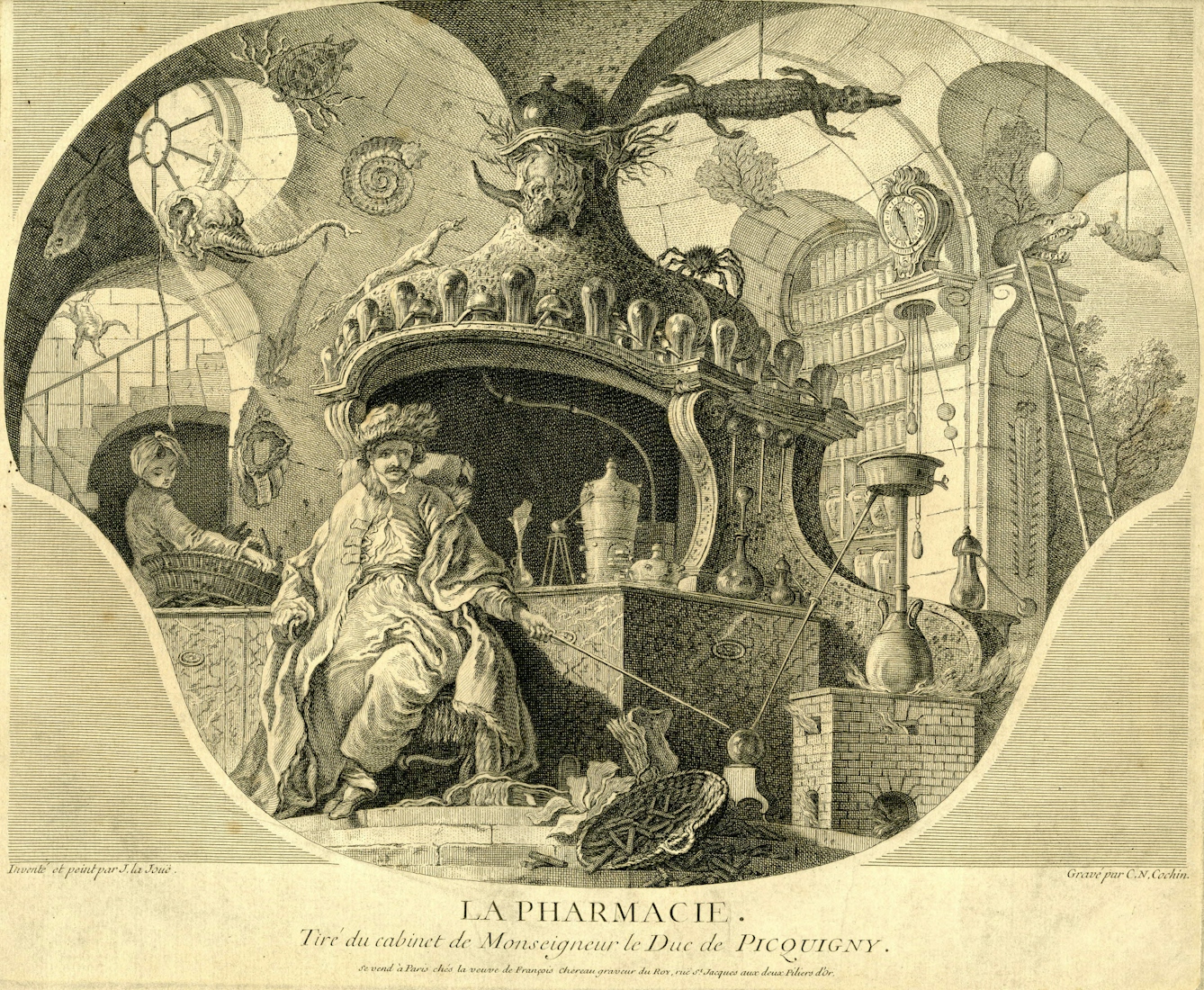

‘La Pharmacie’, engraved by Charles Nicholas Cochin, after Jacques de Lajoue’s painting of the same name, 1738.

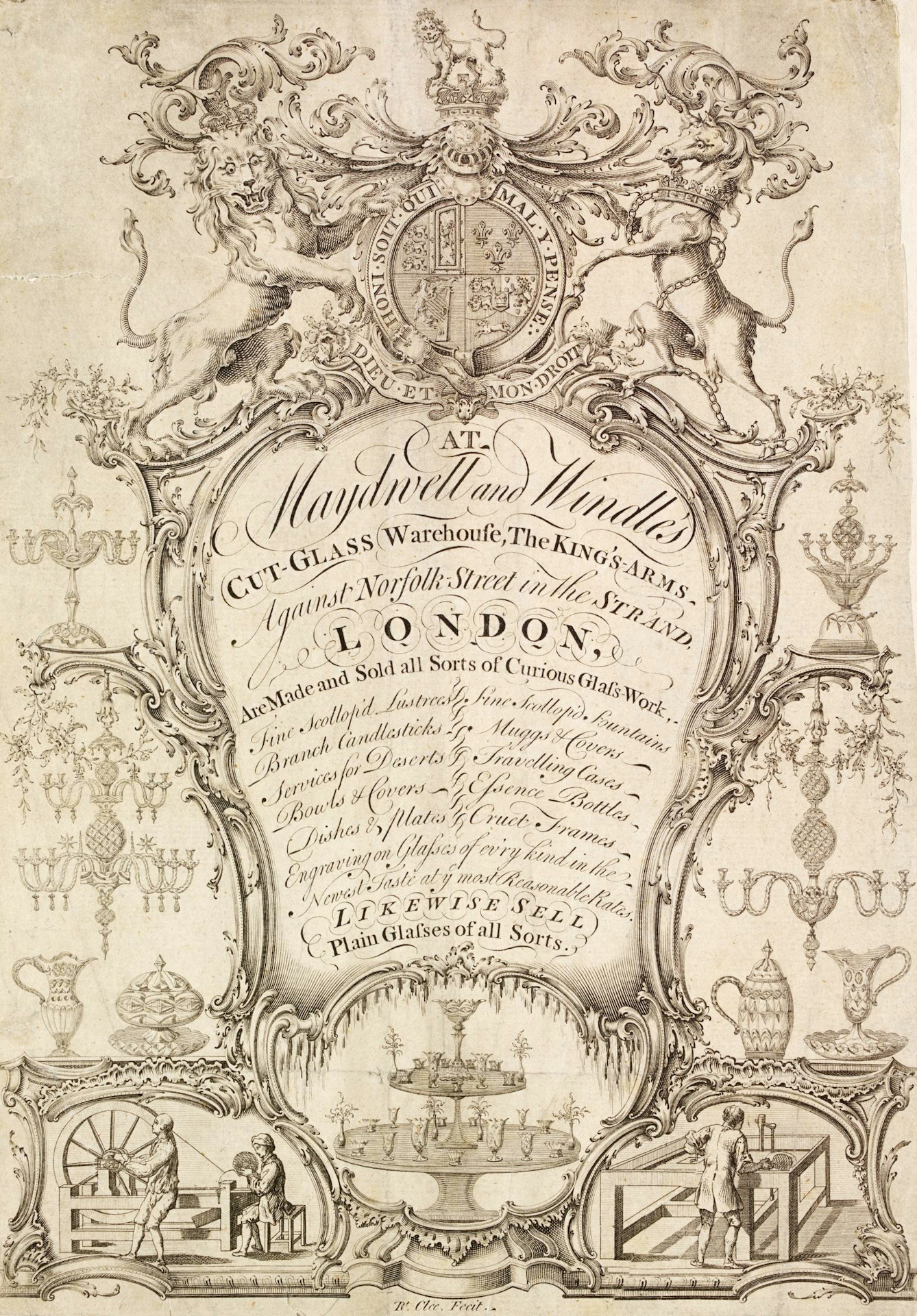

Robert Clee, who engraved Siddall’s card, produced a trade card for his own business in Panton Street, London.

Trade card for Maydwell and Windle, cut-glass manufacturers and retailers, engraved by Robert Clee. The lower half shows scenes from cut-glass manufacture and various cut-glass products including chandeliers, candelabra and glasses. 1750–56.

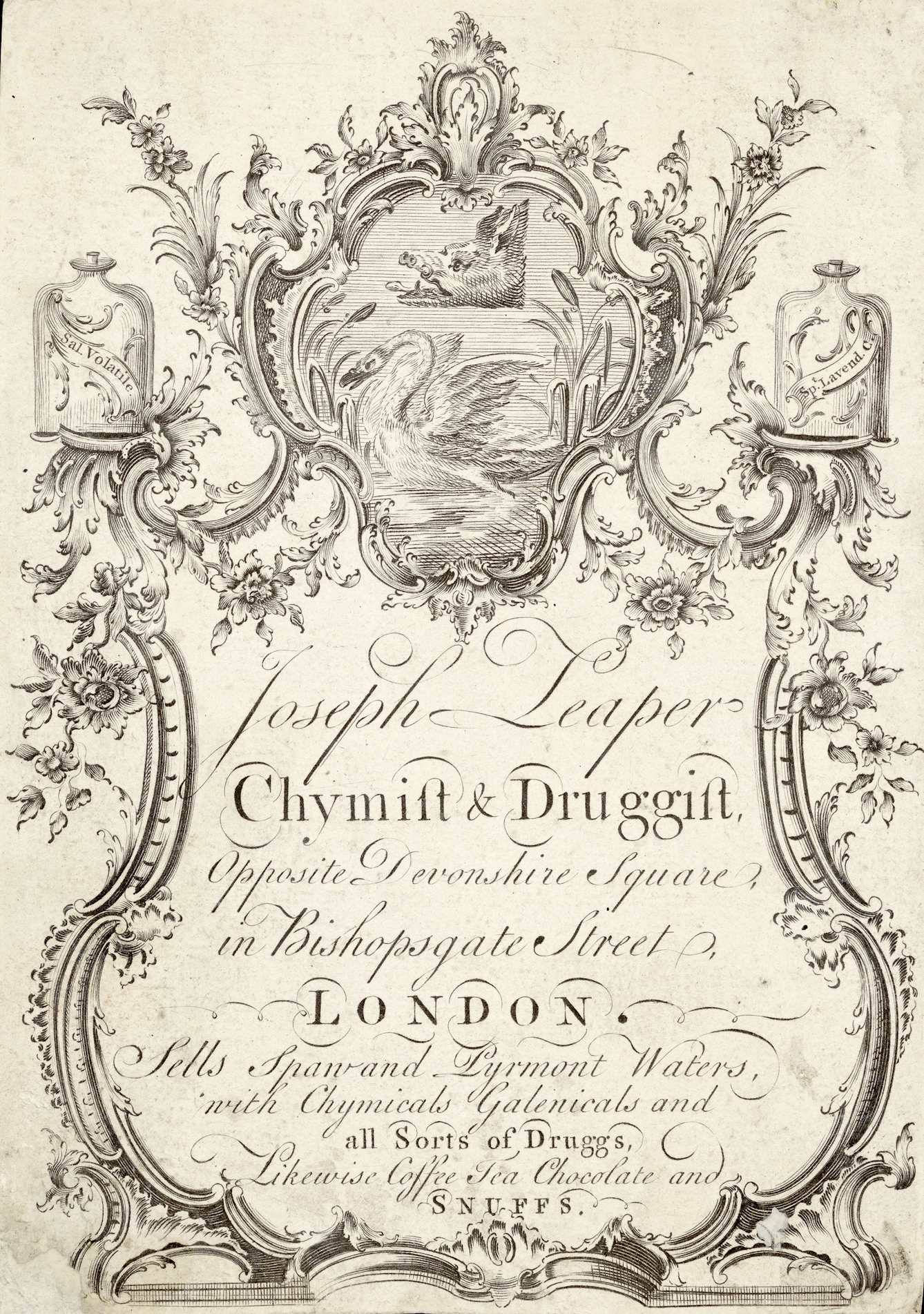

Another chemist, Leaper’s trade card features a swan at the centre, which references his high-street location and former street sign. Leaper sold snuff, a popular pick-me-up, along with coffee, tea and chocolate.

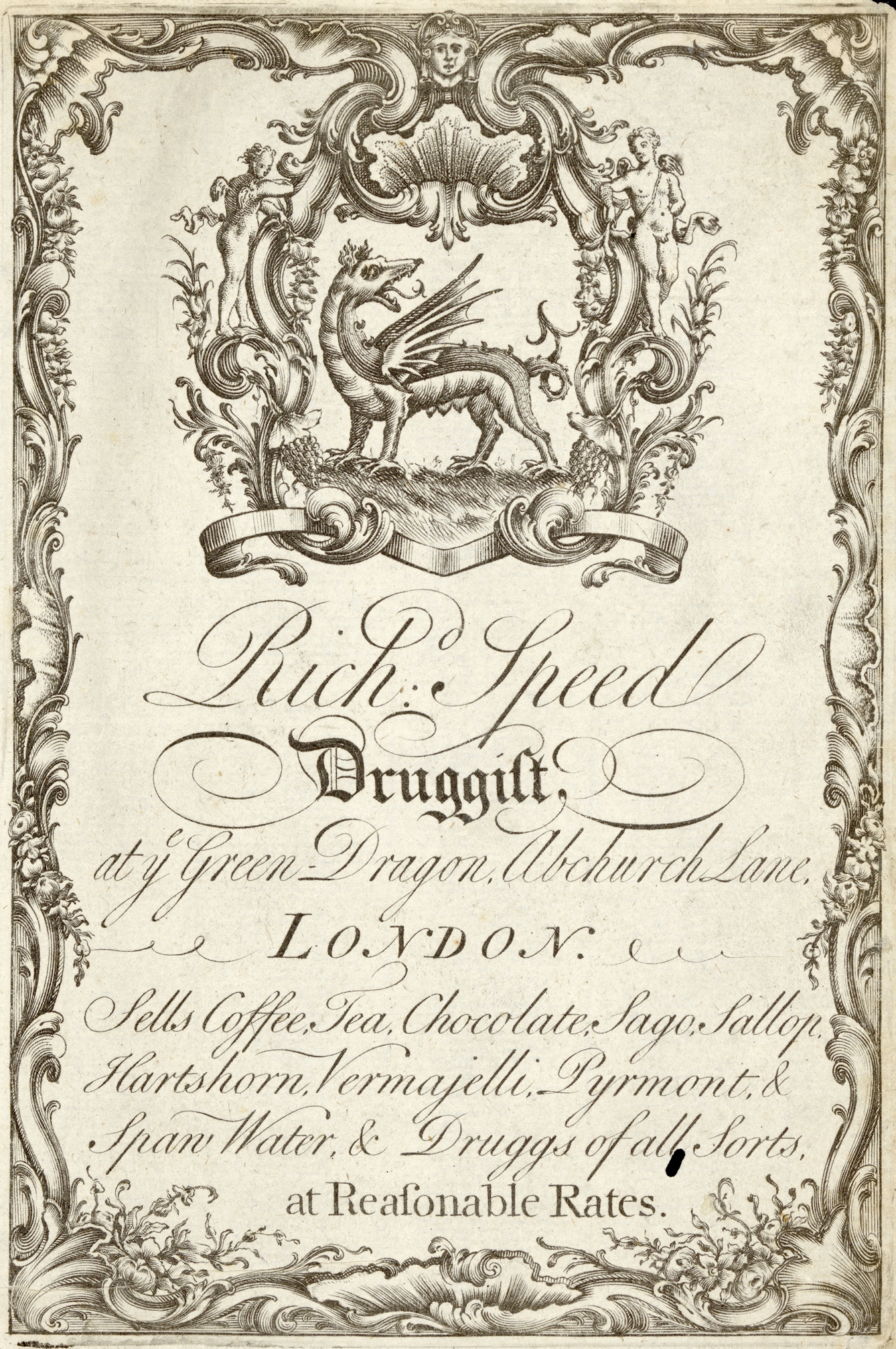

Richard Speed’s trade card has a winged dragon or wyvern, an emblem harking back to the origins of alchemy. Speed calls himself a ‘druggist’ and sells hartshorn, spa water and “druggs of all sorts”.

Robert Clee, who engraved Siddall’s card, also produced cards for neighbouring silversmiths and cut-glass manufacturers in London. Clee himself was well connected. He worked for Charles-Nicolas Cochin, an influential French engraver and designer to Madame de Pompadour. Clee’s design appears to have originated from Cochin’s print version of a fashionable painting entitled ‘La Pharmacie’. This work was one of a series of three by Jacques de Lajoue (1687–1761) on the hot science topics of the day, the others being ‘L’optique’ and ‘L’astronomie’.

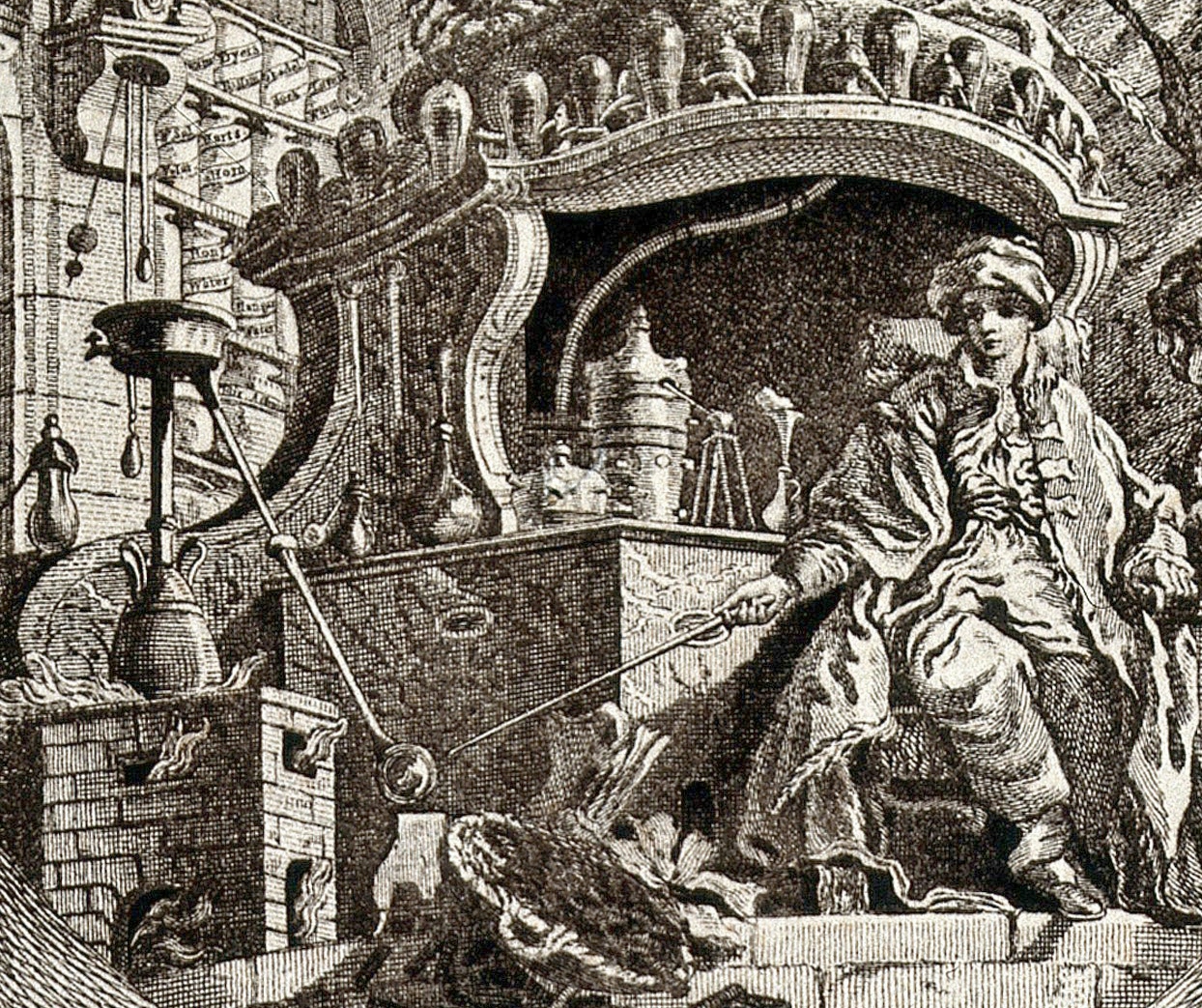

The ‘chymist’ on his throne in Siddall’s trade card.

In Clee’s version, the youthful ‘chymist’ takes centre stage on an architectural throne edged with pharmaceutical vessels. On the surrounding shelves are numerous labelled jars, among them one containing ‘hart’s horn’, a popular ingredient at the time, sourced from the male red deer. This ingredient was used to treat diarrhoea, fever, sunstroke, and insect and snake bites, as well as being a useful detergent and a leavening agent in baking. Next to this is a jar marked ‘sal’ – salt-based remedies remained popular into the 19th century. The second-century physician Galen gazes down on the proceedings as a mark of the chemist Siddall’s learning. Galen was an early practitioner of medicinal recipes – called ‘galenicals’ after him.

Alchemy

This 17th-century painting of an alchemist’s laboratory is similar to Clee’s illustration of the chymist’s laboratory, with a prominent furnace and jars everywhere. Oil painting by a follower of David Teniers the Younger.

Historians like Lawrence Principe have argued that alchemical apparatus (such as this distillery equipment) is a significant connection between alchemical and chemical practices. Alchemy manuscript, 1782.

The alchemist is warned by a young woman, probably Prudentia, not to waste his money on the “fallacious art of alchemy”, which deceives many. One of a series of four prints of the elements, this one portrays fire. Engraving by C. de Passe after M. de Vos, 16th century.

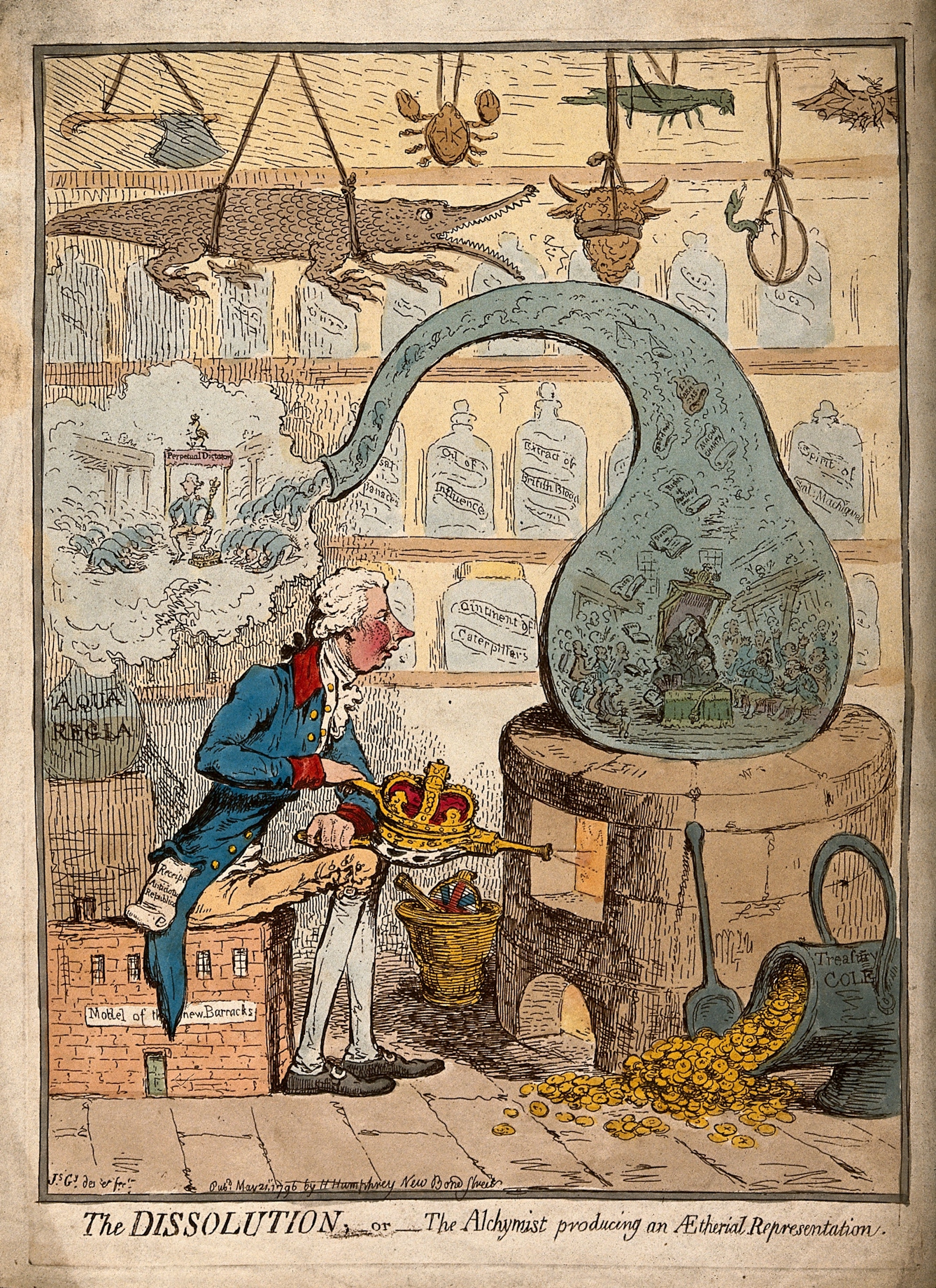

Caricaturists such as James Gillray used the alchemist’s shady practices to satirise questionable behaviour in society. In ‘The dissolution, or the alchymist producing an aetherial representation’, 1796, Prime Minster William Pitt is shown ‘cooking’ the House of Commons, representing the dissolution of parliament.

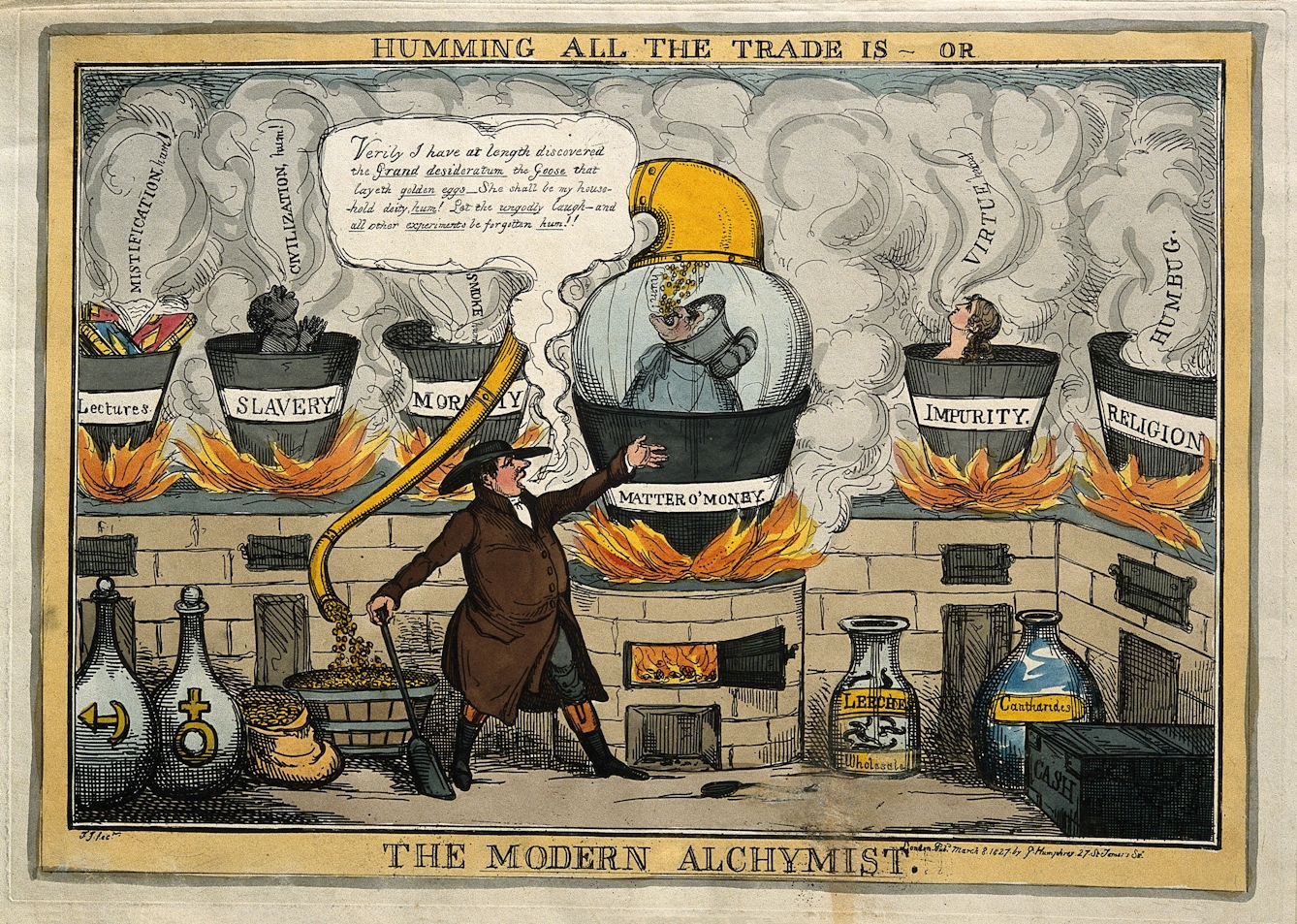

In this caricature, pharmacist William Allen is depicted as an alchemist who has obtained money for nothing (a satire on his marriage to a rich widow). ‘The Modern Alchemist’ by Thomas Howell Jones, 1827.

Other alchemy satires punned on ‘dissolving’: in this case, Britain and its allies are dissolving Napoleon’s control of German states. ‘Political Chemist and German Retorts’ by Thomas Rowlandson, 1813.

Siddall’s trade card also points to the alchemical origins of pharmaceutical practices, as both relied on melting and distilling substances, represented by the brick furnaces and alembic vessels littering the scene. Originally, alchemy was a secretive activity, with its own complex and mystical imagery. By the 1740s it had become distinct from chemistry, and alchemists were popularly regarded as charlatans.

A woman with a basket in the background of Siddall's trade card.

A woman holding a basket serves as a reminder that, traditionally, the art of distilling was the domain of women. It was a skill that involved techniques similar to those used in cooking, as suggested by the title of Sir Hugh Plat’s book ‘Delightes for Ladies to Adorne their Persons, Tables, Closets, and Distillatories’ (1602).

Women working in a distillery. Image from ‘Georgica Curiosa Aucta …’, published in Nuremburg, 1716.

As chemistry overtook alchemy in the mid-18th century, the field of pharmacy widened and drug makers of all kinds proliferated. While apothecaries, licensed by the Royal College of Physicians, dominated the official manufacture of pharmaceutical products, there were plenty of experienced and unqualified tradesmen who practised as chemists and druggists. These shifting boundaries between alchemists, chemists, apothecaries and druggists in the mid-18th century are encapsulated in the design of Siddall’s trade card.

About the author

Julia Nurse

Julia Nurse is a collections research specialist in the Research team at Wellcome Collection with a background in Art History and Museum Studies. Her work focuses on the pre-modern period, especially the interaction of medicine, science and art within print culture.