The Hindu concept of darshan means “divine revelation”, but it’s also about the multilayered ways in which we see the world around us. Adrian Plau explains how a deceptively simple image in a Panjabi manuscript relates to darshan, and why it’s one of the most striking images he’s ever encountered.

The eye of darshan

Words by Adrian Plauaverage reading time 5 minutes

- Article

If you think, my lord, that I may see your true form,

Then, master of senses, show me your endless self.

These words are spoken by the warrior Prince Arjun to his charioteer, Krishna, in one of the most famous divine revelations in all of literature: the Bhagavadgita (Song of God).

At this moment when Krishna reveals his divine form, Arjun receives darshan – the experience of glimpsing a deity or anyone deemed holy. In Hinduism, ‘taking darshan’ is a central part of visiting a temple to view its deities. The moment of darshan also suggests the many realities underlying the world as it appears to us. As such, darshan presents a subtle idea of how every one of our waking moments is layered with many ways of seeing.

When Arjun speaks of seeing in the Bhagvadgita, the Sanskrit words for ‘see’ draṣṭum, and ‘show’, darśaya, are derived from the same verbal root: dṛś. It expresses ‘seeing’, but also ‘glimpsing’, ‘intuiting’ and ‘realising’, and points towards the fleeting but revelatory nature of any insight. These and many other nuances are captured in the word darshan.

Panjabi manuscript 255.

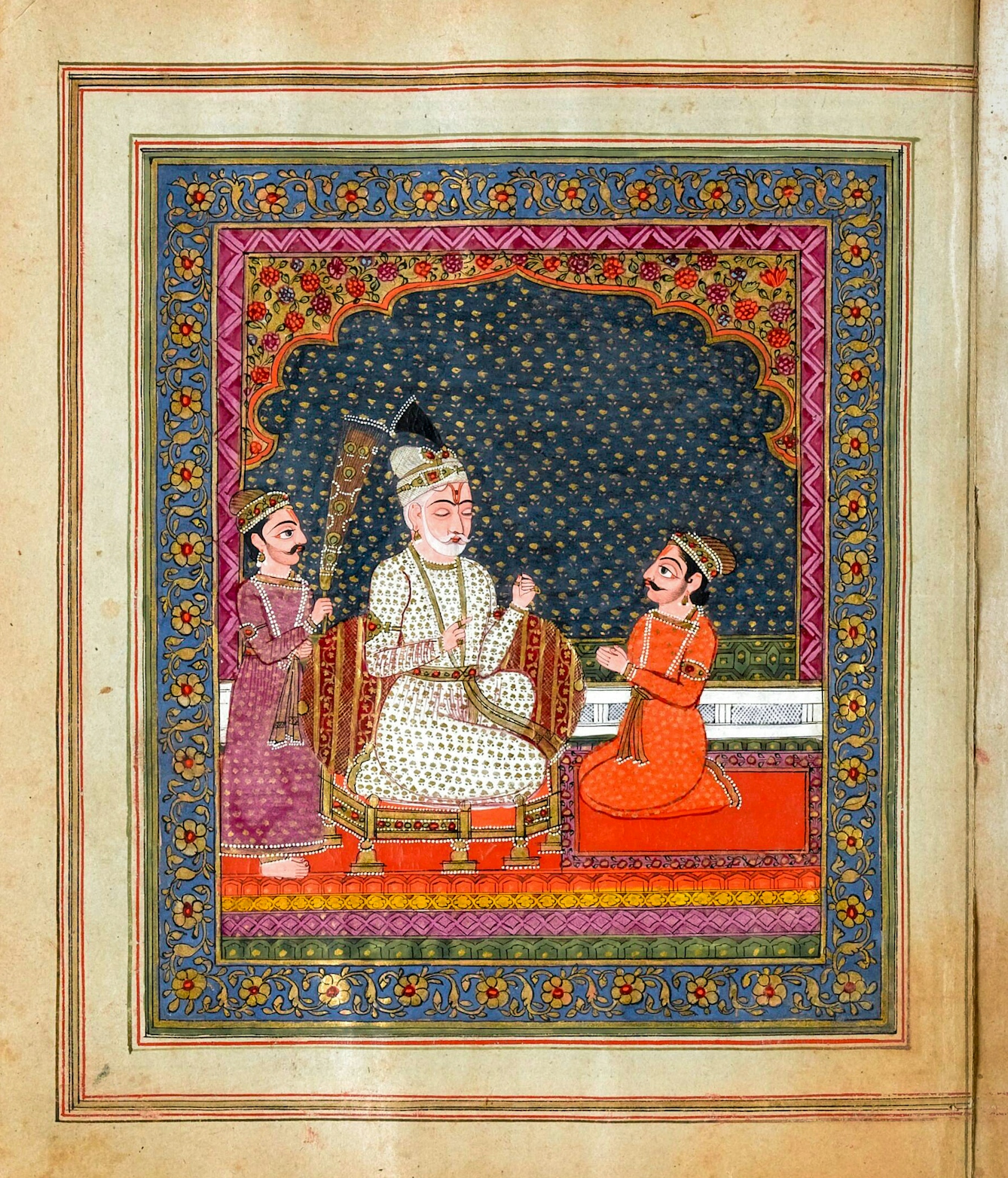

This image from an elaborately illustrated manuscript of the Bhagavadgita (Wellcome Collection MS Panjabi 255) shows King Dhritarashtra seated on his throne, eyes shut, fanned by a courtier to his side, and apparently listening to Sanjay, another courtier, kneeling before him. But this is a deceptively simple scene once you understand what is happening.

Dhritarashtra’s advisor Sanjay was given the gift of ‘far sight’ by the sage Vyas. Thanks to his ability to see things at a distance, Sanjay provides Dhritarashtra, who is blind, with live updates and commentary on everything that is happening in the distant war involving Dhritarashtra’s sons. This war is at the heart of the Hindu epic the Mahabharata and it is in the midst of this war that Arjun receives the Bhagavadgita from Krishna.

What we see in this image is the moment when Sanjay describes Krishna’s divine revelation to Dhritarashtra. When Krishna reveals his awe-inspiring divine form, he asks Arjun to “Behold!” (paśya), subtly shifting to another verbal root for ‘sight’, with far more assertive connotations.

It is through the third eye of darshan that you receive insight, and hence wisdom.

To sum up this image, a blind man is listening to a farsighted man describing how another man was temporarily given a ‘third eye’ so that he might witness a divine revelation that human sight alone simply could not fathom. In other words, the three men, Dhritarashtra, Sanjay and Arjun are ‘seeing’ the events unfold, each in their own way.

The stillness and deep concentration on Dhritarashtra’s face hints at the enormity of what is being revealed, but it is significant that for all the many vivid images of Krishna’s divine life in this manuscript, the artists who created it did not provide a single illustration of the actual revelation. That moment of darshan transcends ordinary vision.

The difference between seeing and knowing

The tension between the seen and the unseen pervades discourses around darshan. In a rare manuscript (Wellcome Collection MS Hindi 314) of the 19th-century treatise ‘On English People, the Servants of Jesus’, the Jain mendicant Ratanchand challenges the rational stance evident in the critiques of Asian philosophies and religions by Christian missionaries in British India.

Orientalist perspectives have been quick to present South Asian culture in overly mystifying ways. In his text, Ratanchand implies that darshan, as a philosophy of seeing, did not develop in the absence of an empirical understanding of vision, but as something that enhances and goes beyond human sight:

“You ask of me how it is that the holy Mount Meru stands one hundred thousand yojana tall and yet we cannot see it?” writes Ratanchand. “We don’t see it through the mirror of the eye, but through wisdom. Eyes can only see like telescopes do, but the light from Mount Meru shines in our wisdom.”

Empirical understanding, by relying on the senses alone, Ratanchand argues, can only take you so far. It is through the third eye of darshan that you receive insight, and hence wisdom.

The blind poet’s revelation

Darshan as insight, then, is something that is potentially accessible by anyone – whether they are sighted or blind or farsighted – if they seek it.

There is perhaps no better encapsulation of the tension between failing eyesight and deep insight than the influential North Indian blind poet and singer Surdas, who is thought to have lived in the first half of the 16th century. Surdas is himself the subject of myriad stories and traditions, and his poetry is imbued with an almost unbearably keen sense of a reality that is simultaneously worldly and visionary.

In his late poems, Surdas ruminates on his life, his mortality, and his relationship with God. A beautiful 18th-century manuscript written in Nastaliq (a Persian/Urdu script) containing a large compilation of his poetry (Wellcome Collection MS Hindi 369) gives an example of his later reflections on God and darshan, and what truly it means to see:

I have travelled so far to see you, for your darshan,

And I forgot that you rule everywhere.

Thoughts, words, deeds cannot reach you.

That is the image that I did not think about seeing.

Sometimes you have to be able to imagine a thing in order to see it.

You can see the image of King Dhritarashtra being told about Krishna's divine revelation from manuscript MS Panjabi 255 at the exhibition 'In Plain Sight' at Wellcome Collection until 12 February 2023.

About the author

Adrian Plau

Adrian Plau is Manuscript Collections Information Analyst at Wellcome Collection, and a recent Headley Fellow with the Art Fund. He holds a PhD in South Asia Studies from SOAS.