German physician Georg Bartisch (1535–1607) was both ahead of his time and a product of his time. On the one hand he was a knowledgeable surgeon who closely observed the human body; on the other he believed that disease was a punishment from God.

Bartisch wasn’t academically trained in medicine, but started his career as an apprentice to a barber surgeon when he was 13. He travelled with his work and grew in renown, finally settling as oculist to Duke Augustus I of Saxony.

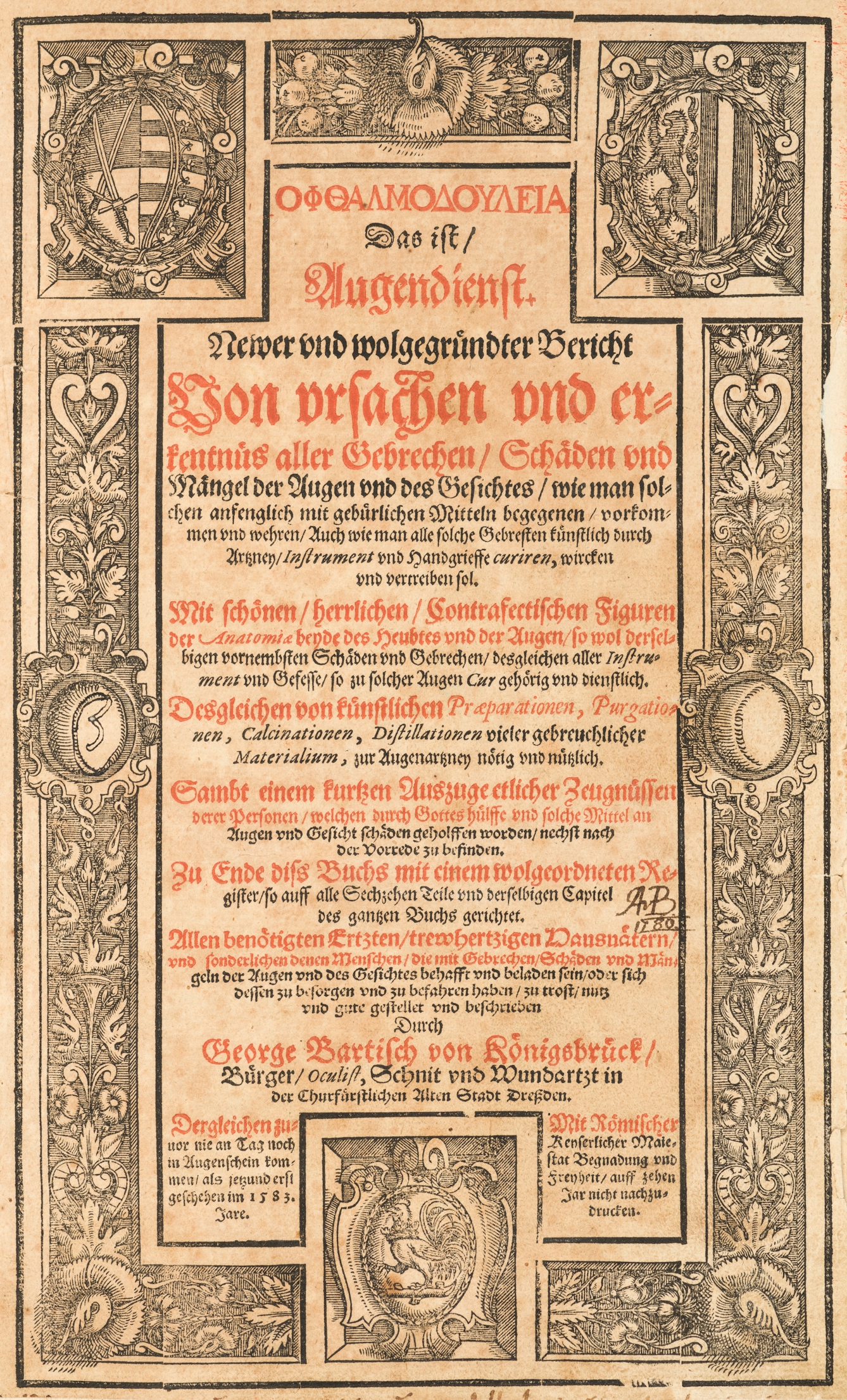

Based on his specialist knowledge of the eye, Bartisch published ‘Ophthalmodouleia’, the first known Renaissance manuscript on ophthalmic disorders and eye surgery. The publication is the reason he is remembered in the world of ophthalmology, and he seemed quite aware of his work’s significance even at the time. In the manuscript’s title page, he wrote: “The likes of this have never appeared until now in the year 1583.”

Bartisch is not particularly sympathetic to his patients’ complaints. “Some patients are so fine, soft, and squeamish when they are blind or otherwise have poor sight. They want nothing done to their eyes,” he says. When you look at the gorgeous but gruesome woodcut pictures printed alongside the text, it’s not hard to understand why a patient would, in Bartisch’s words, “whimper and whine about the cure and the medicine”. Especially with no anaesthetic.

Bartisch regularly alludes to stories from the Bible, explaining that only Christ could have used the method that his patients seem to want – just a word or a touch. How could he, a mere mortal, offer such a cure? Bartisch believed that eye disorders – like other illnesses – were caused by God, stating, “Such earthly and physical punishments happen and are enacted. These are diseases or afflictions of the body.”

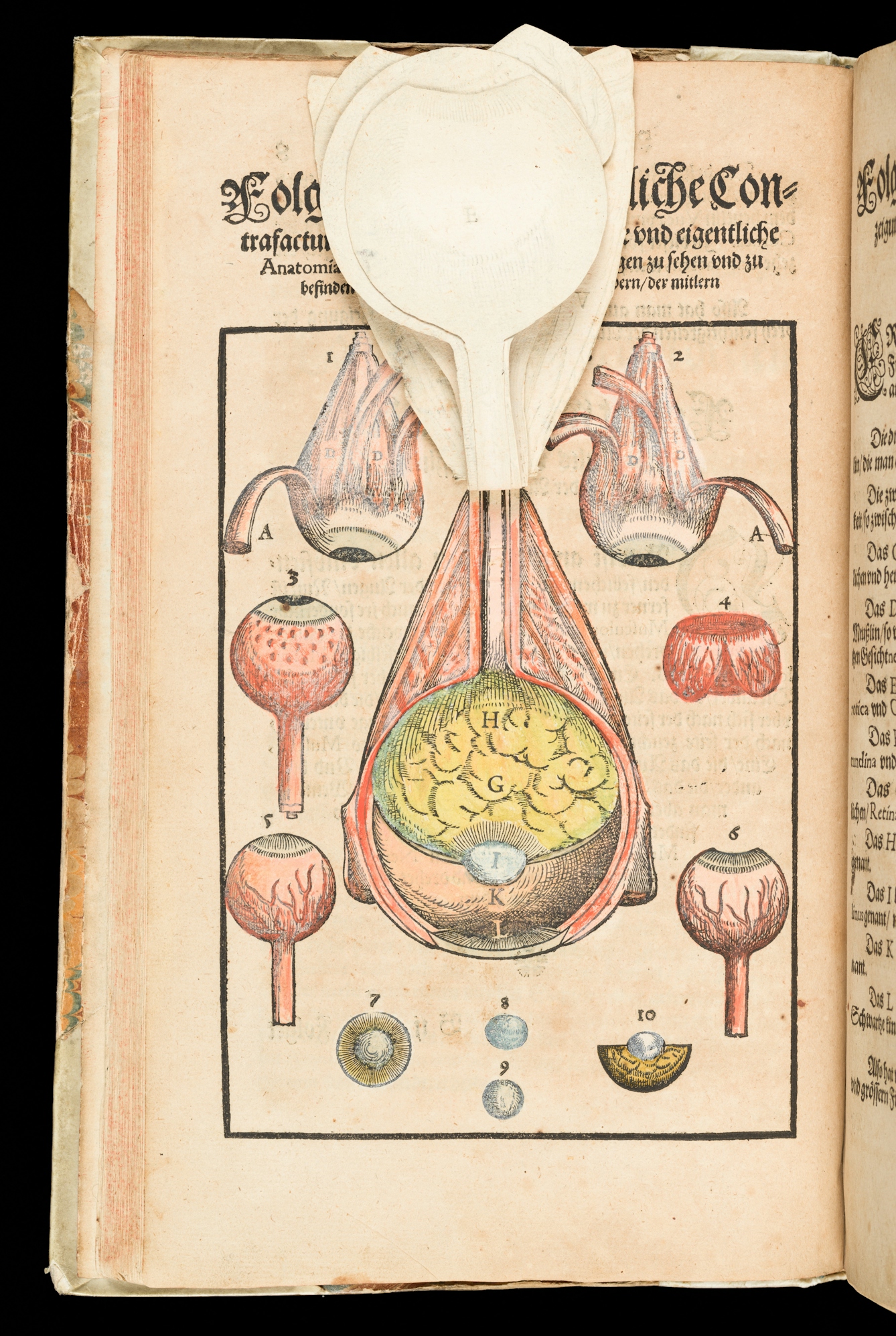

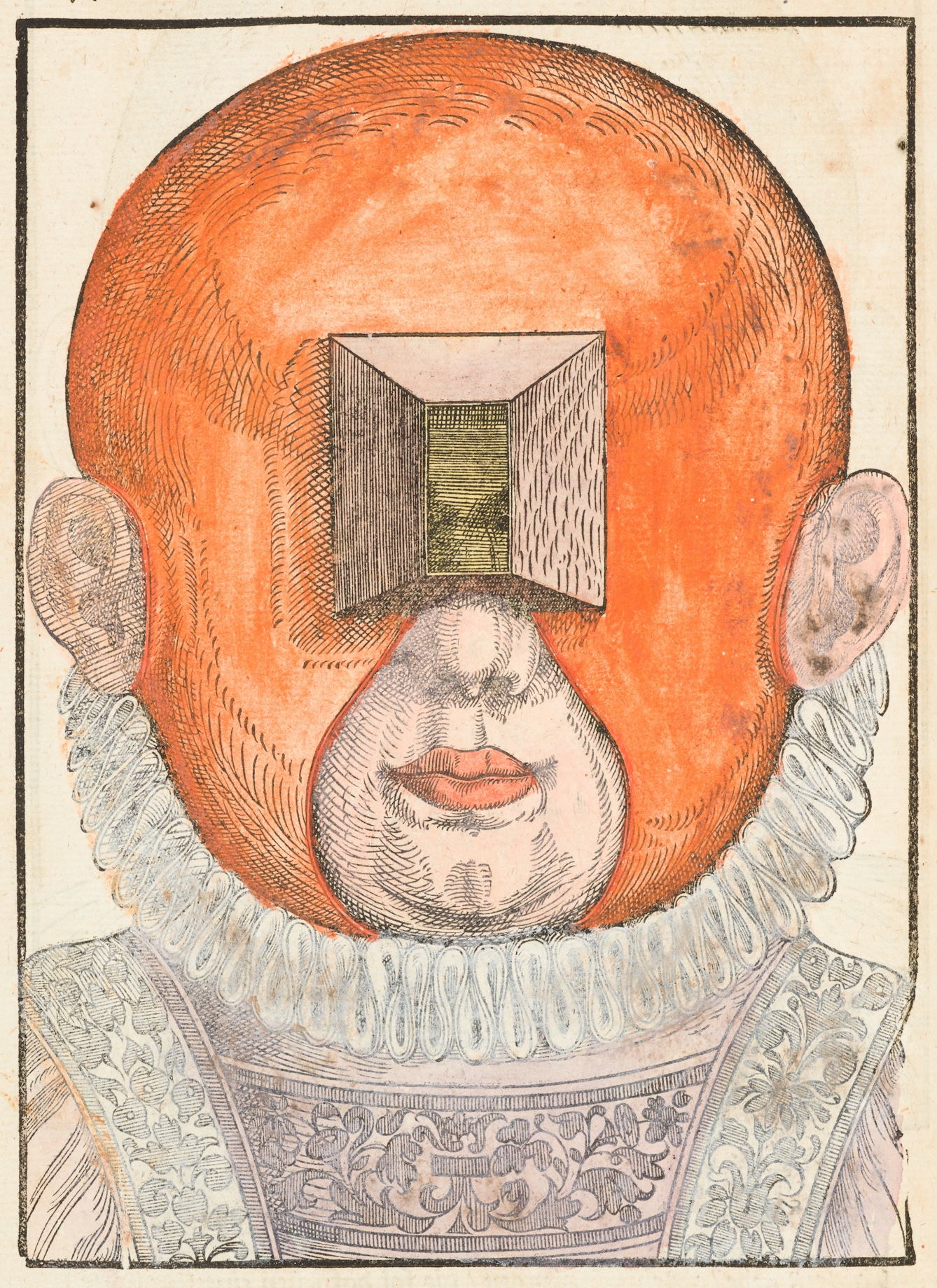

One of the manuscript’s most striking features is the illustrations, some of which include flaps that you can move away to reveal layers underneath. Bartisch comments on an image of one of his treatments, but it could apply to any of the images in his work: “This following representative figure shows this in a way that is easier to see and understand than if one were to write three or four full pages.”

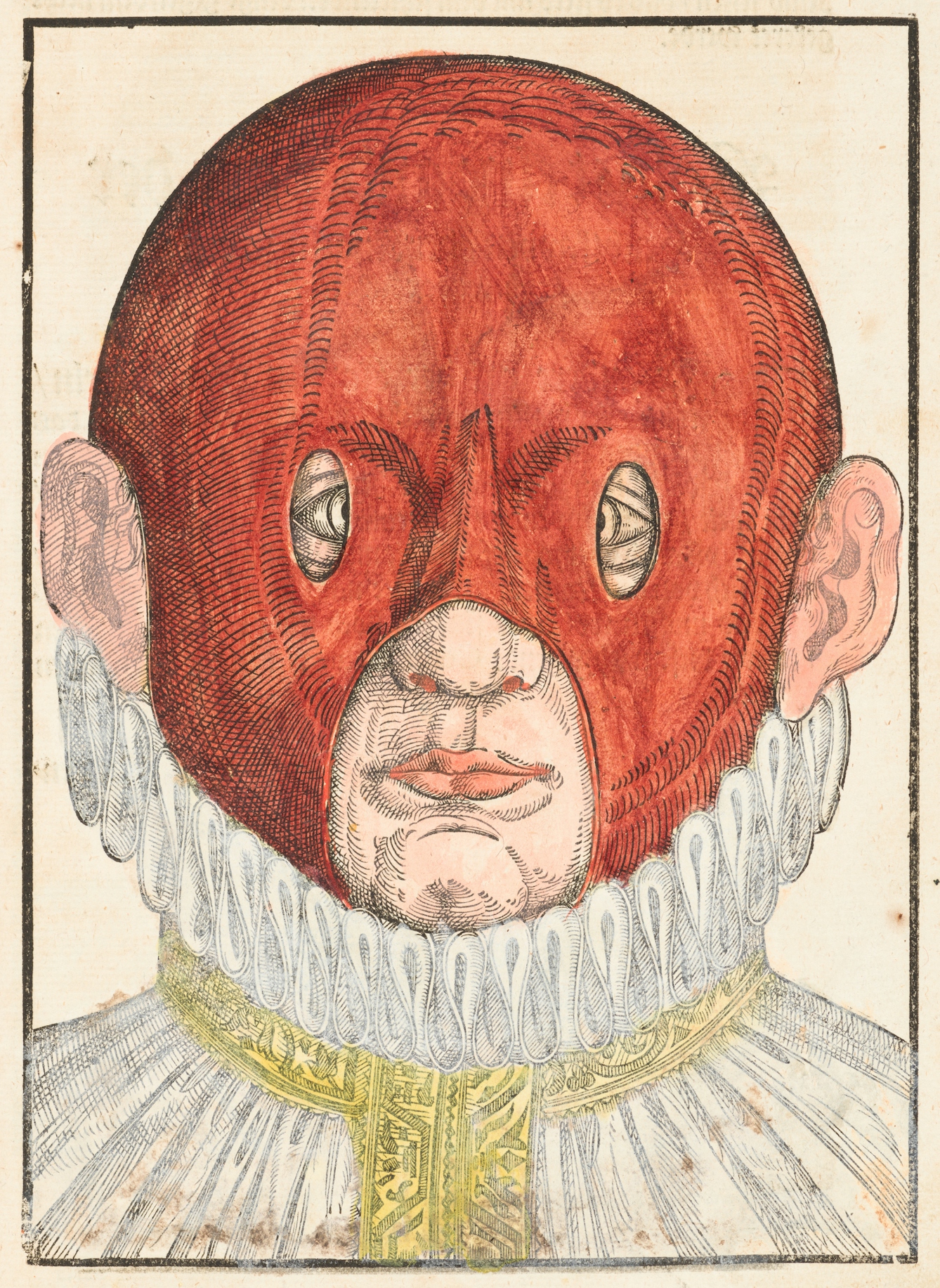

Bartisch discusses treatments for conditions such as strabismus, which is often referred to as ‘crossed eyes’. We know now that family history can affect someone’s likelihood of developing the condition, but Bartisch’s interpretation is much more extreme. According to him the condition is caused in children “through waywardness of the mother”, who could be distracted by “shiny exposed wares, fire and storms, lightning, gunshots, sun reflecting in the water”.

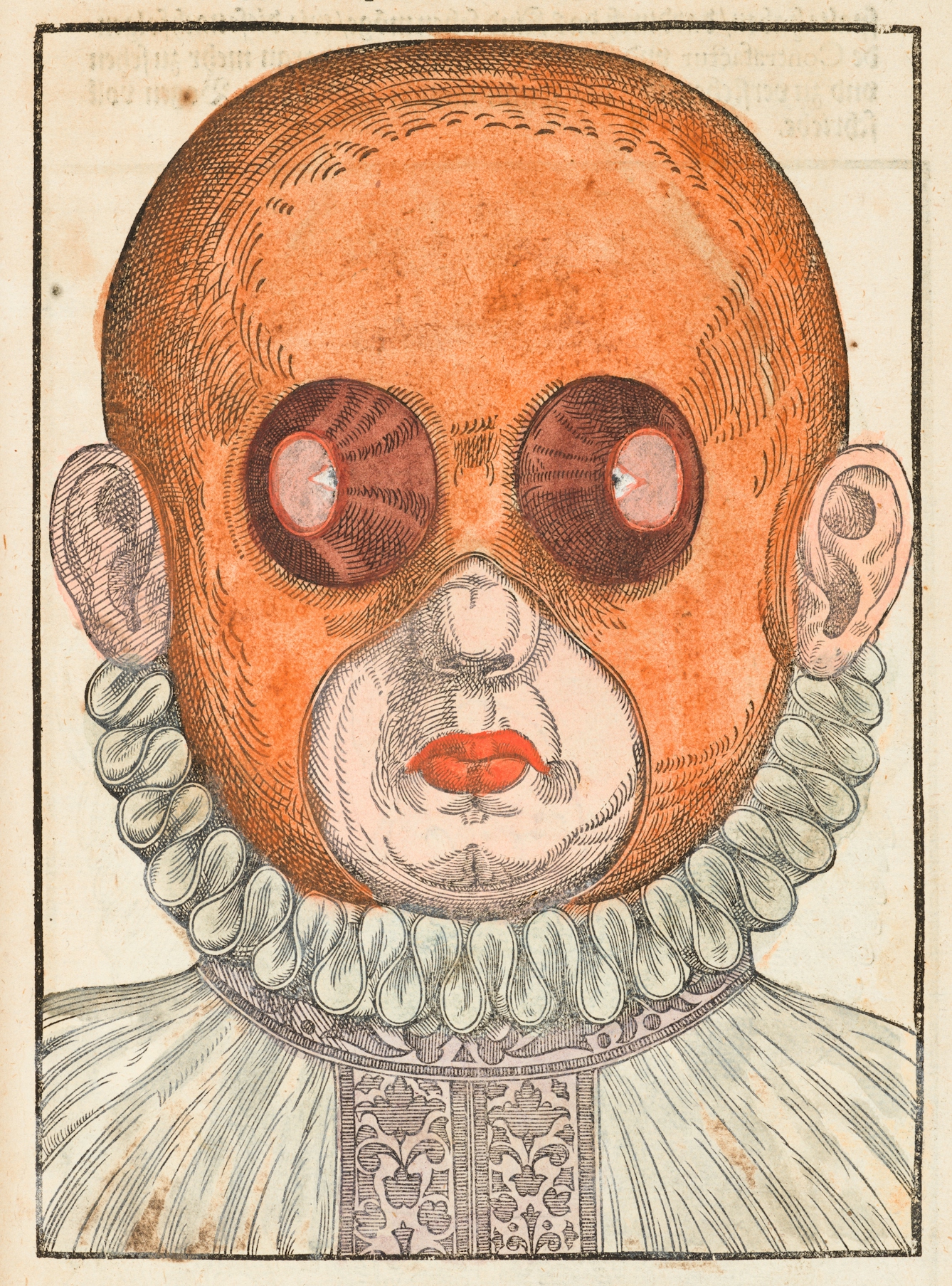

To cure strabismus, Bartisch suggests training the eye through wearing a corrective mask, as the image shows. The mask is different depending on whether the sufferer turns their eyes outwards towards the ears or inwards towards the nose. This is not very different from a vision-therapy course that a doctor might prescribe today.

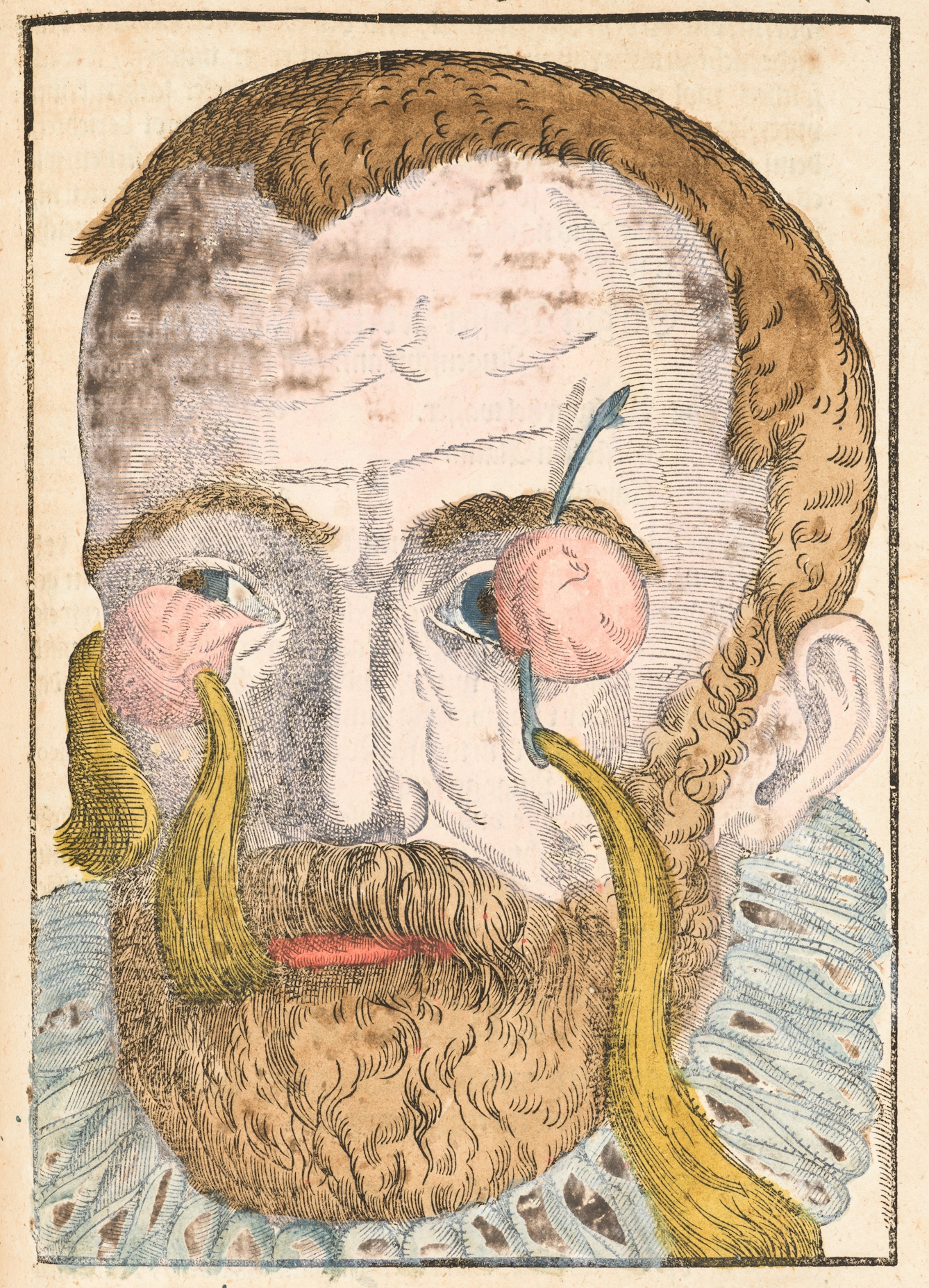

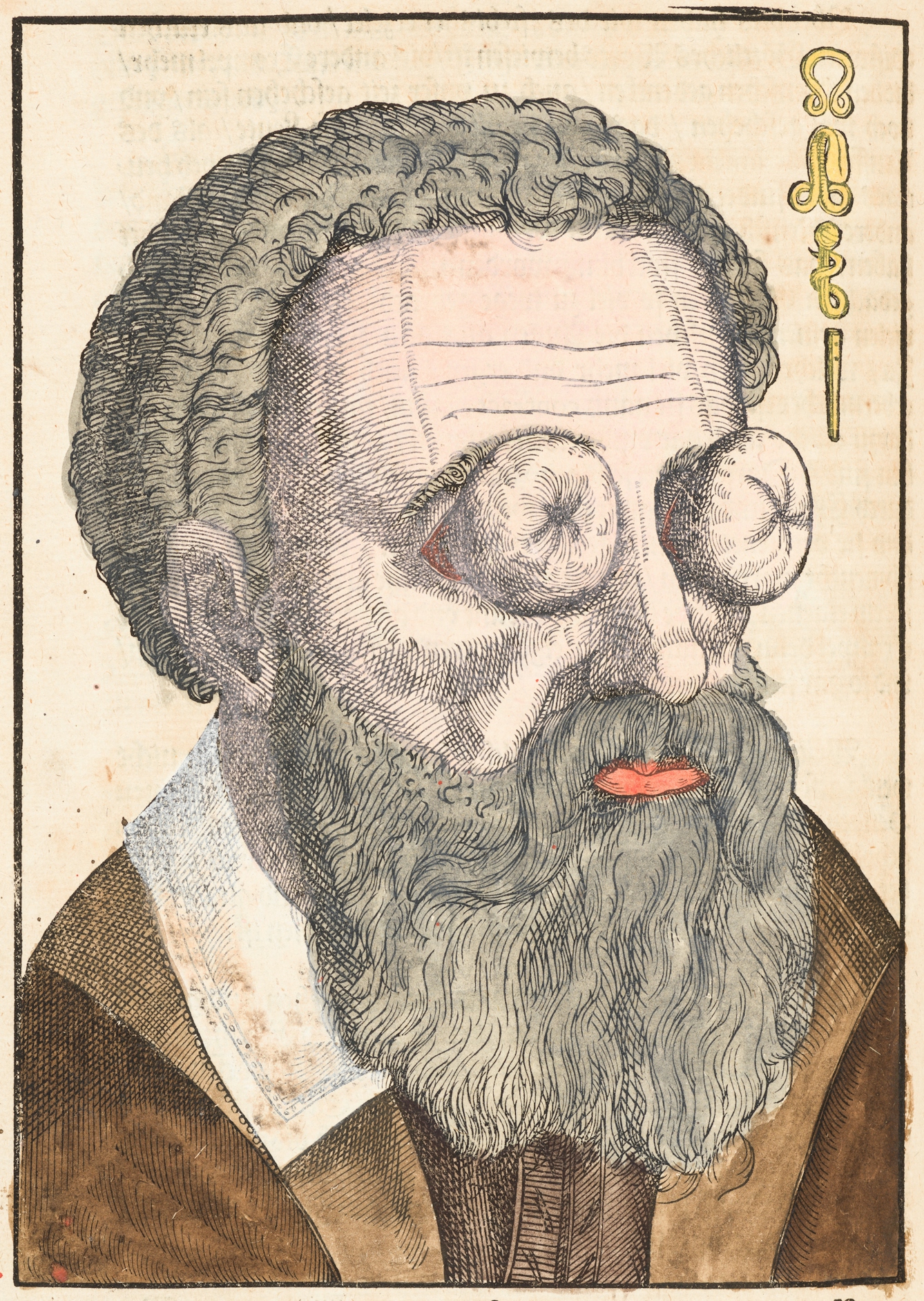

‘Ophthalmodouleia’ ends with a long section on witchcraft, which includes the image of a man whose eyes resemble two squash-like vegetables. “Who can or may say that this is supposed to be natural and not from witchcraft?” Bartisch asks. He goes on to explain that “the primary and best help for this affliction and defect is the protection of God”. Fortunately, God bestows the world with people like Bartisch, who know the best remedies. In this case it was “a noble head wash for hot eyes”, made from ingredients such as great figwort and columbine herb, chopped up fine and cooked in water.

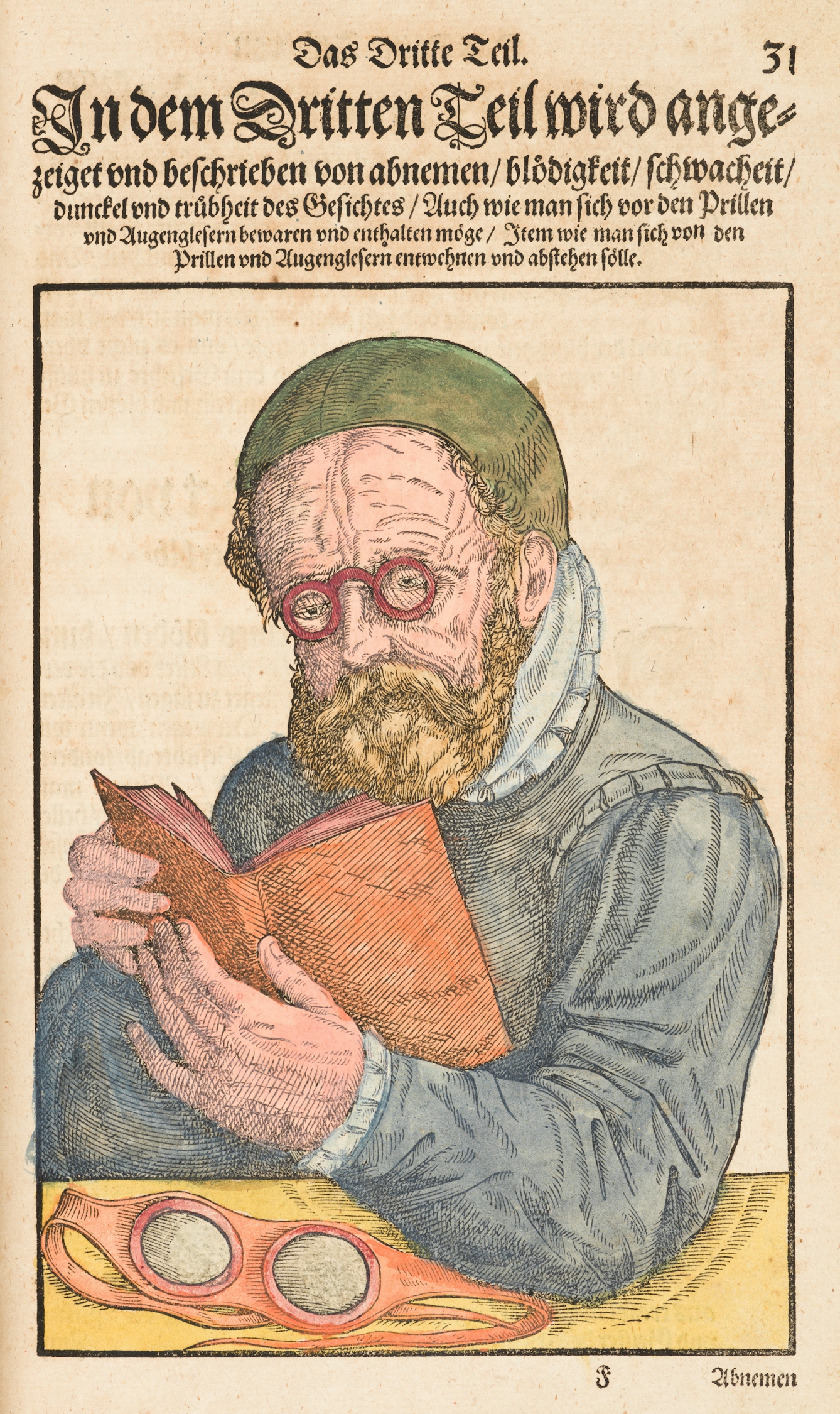

Though he promoted ocular health, Bartisch was against wearing glasses or spectacles; for him it was insulting to suggest the use of glass could improve the function of such an intricate organ.

Bartisch’s text was influential, not only because of what he wrote but also how he wrote it. He used the more widely accessible vernacular German rather than Latin, which was at the time the typical language for academic publications. Ultimately, his idiosyncratic but detailed knowledge about eyes and how to treat them have survived thanks to ‘Ophthalmodouleia’. This is why he’s remembered today as the father of ophthalmology.

About the author

Kate Wilkinson

Kate works at Pushkin Press. When not submerged in a book, she can be found walking or practising Spanish. Sometimes both at once.