When we bring someone in hospital a bunch of grapes, we don't expect the grapes to work a miraculous cure upon them. But several times in history, wondrous healing powers have been attributed to the humble grape. Follow the history from ancient Greece, to early modern treatises on why we should drink wine instead of water, to early 20th-century luxury health resorts where nothing but grapes were served.

Today, if we describe something as bacchanalian, we are implying that it’s a drunken party and definitely not that it might be healthy. But the religion of Dionysus (as Bacchus was known by the Greeks) emphasised the importance of consuming the correct amount of wine to ease suffering. The idea that wine or grapes can keep us well or even cure us has cropped up many times since.

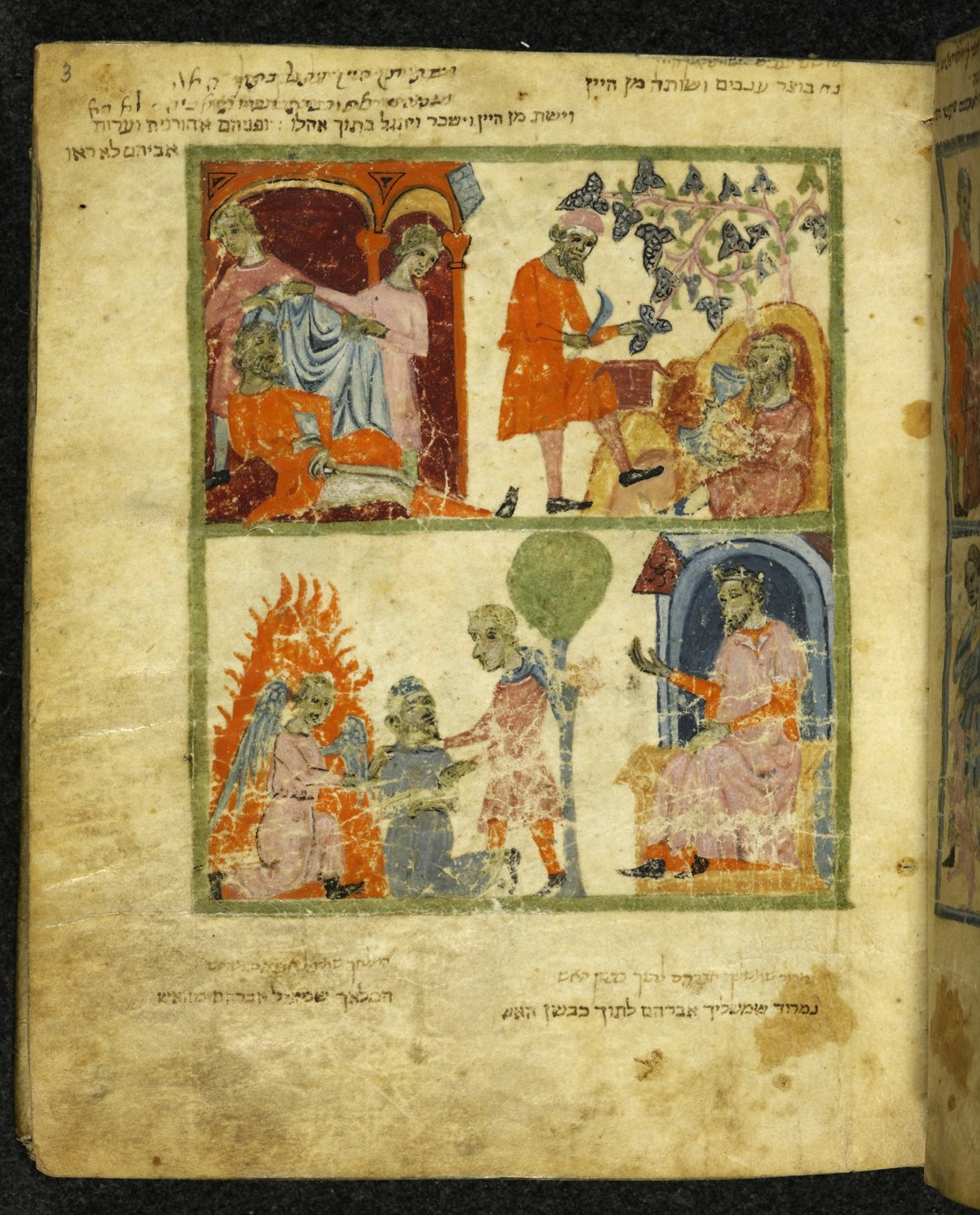

In 1638, a “Doctor in Physick of London” called Tobias Whitaker sought to prove “the possibilitie of maintaining humane life from infancy to extreme old age without any sicknesse by the use of wine”. He used humoral theories and ancient philosophers like Aristotle and Galen to make his case, as well as the Bible: Whitaker claimed that Noah lived to be 950 years old and the first thing he planted after disembarking the Ark was a vine, therefore wine must be important to longevity.

A century later, Enlightenment ideals were fashionable. Peter Shaw (1694–1763) of the Royal College of Physicians reflected these ideals in his writing, where he emphasises the logic of drinking wine as a “grand preserver of health”. Shaw explains that the time to recognise wine has come, as people are becoming disillusioned with more elaborate cures made from less familiar ingredients “if Reason will not warrant the use of it”.

By the 19th century, scientists were beginning to break down foods and measure constituent parts, like sugars. Based on this sort of study, French doctor Jean-Charles Herpin stated that grape juice “is a kind of vegetable milk, the chemical composition has the greatest analogy with that of woman's milk”. He believed that people should consume almost exclusively this “herbal tea sweetened by nature herself”.

Capitalising on such claims about the miraculous health properties of grapes, trendy resorts in Germany, France and Italy offered their wealthy clients summer-holiday “grape cures”. The Kurhaus in Baden-Baden is a glamorous resort formerly favoured by wealthy and famous visitors like Fyodor Dostoyevsky and Marlene Dietrich. This photograph shows waiting staff and plates piled high with grapes for guests to partake of the Traubenkur, as it was known in Germany.

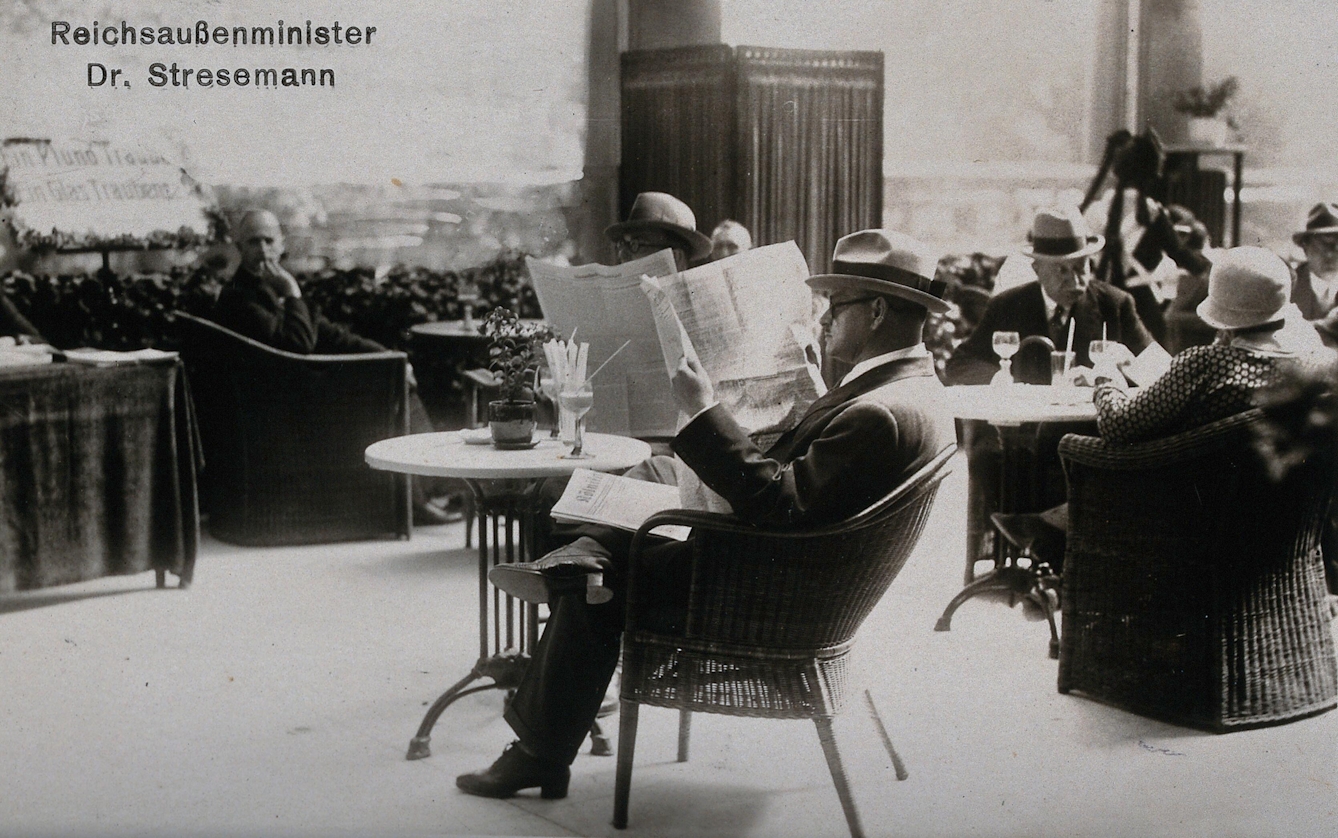

Grape-cure resorts attracted some notable clients. Nobel Prize-winner Gustav Stresemann, Chancellor and later Foreign Minister of Germany, is pictured enjoying a newspaper on the terrace in this 1920s photograph of a Baden-Baden resort. Stresemann often took his summer holidays in the area, but his health problems persisted, and he died in 1929 aged 51. Some historians have speculated whether, had he lived, he might have been able to limit the rise of Hitler – if only the grape cure had worked!

Not everyone was impressed by grape chemistry. Thomas Linn wrote that the health benefits of grape cures have “been exaggerated” and their nutritive value was not great. More alarmingly: “Some two pounds daily are the usual treatment, but this is not so agreeable as it might seem. The fruit irritates the gums and mouth so that a weak solution of soda has to be used after eating them.”

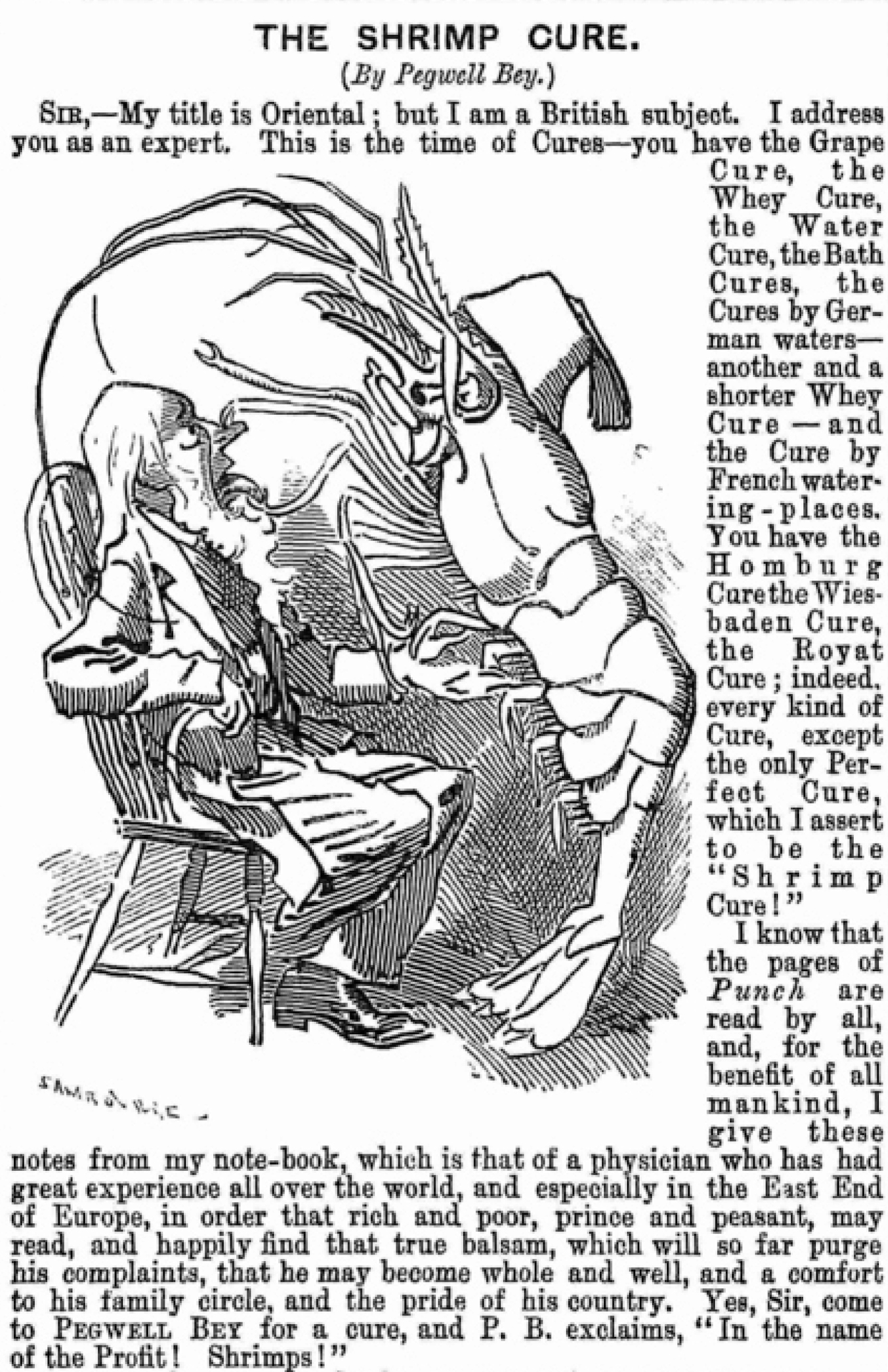

Punch magazine declared 1887 “the time of Cures” and mocked people’s gullibility for following food-limiting fads like the grape cure. Mocking anecdotes of “miracle cures” (and their often worse side-effects), the article describes a duke who had tinnitus and migraines but then took the “shrimp cure” and consequently began assaulting people and eating his newspaper, “But I fancy the noises in his head have disappeared.”

In the mid-20th century, with greater availability of imported foods, grape cures came within reach of people trying to cure themselves at home. In 1927, Afrikaner Nationalist and spy Johanna Brandt wrote ‘The Grape Cure’, in which she claimed to have had stomach cancer and to have cured it by eating nothing but grapes. Various legal rulings went against the organisation she set up, but companies hoping to profit from people’s hopes by selling grape juices and extracts continued to promote the book.

Brandt’s ideas were picked up by fans of physical culture (what we might today call health and fitness) and in 1950 bodybuilder Bernarr Macfadden offered $10,000 to anyone who proved that grapes could not cure cancer. However, within a year his foundation had stopped selling either Brandt’s book or their own grape pamphlet. Noting that “quacks cause deaths” by offering such false promises of miracle grape cures, the American Cancer Society investigated repeatedly and found no evidence of any benefit to following the grape cure.

Others were more modest about the grape itself and endorsed the lifestyle the grape represented. In 1951, Dr von Hartungen, a doctor from a dynasty of spa physicians, advised eating a bunch grape by grape as an antidote to hurried meals. He hailed grapes as a cure for the urban problem of obesity, especially when combined with the “Oertel cure” of hiking and climbing. Reflecting his atomic era, Hartungen said that “radio-active” Merano grapes and local hikes were especially rejuvenating.

Grapes and wine continued to be associated with healthy lifestyles. In the 1980s and 1990s, the “French paradox” was often in the media: French people appear to have low levels of coronary artery disease despite a high-fat diet. An episode of American TV show ‘60 Minutes’ suggested that red wine was the main reason and sales of red wine in the US soared, despite a lack of evidence.

In the 21st century, grapes are still promoted as a cure for modern life. The Times reported in 2002 that health gurus said the humble grape could “neutralise the free radicals generated by smoke and pollution” and prevent skin ageing. Grape seed is used in anti-ageing pills (non-irradiated, unlike von Hartungen’s radio-active grapes!) and fashion magazines promote grape-cure resorts as places to ‘detox’ and lose weight. Explanations are now different, but the ‘prescriptions’ are remarkably like those given for hundreds of years.

Today, researchers are studying the potential of chemical substances within grapes to treat cancer and cardiovascular disease. We may yet have a legitimate “grape cure” one day, but studies haven’t yet reached human trials; they are currently only looking at cells and rodents. In the meantime, if you know someone unwell, a traditional bunch of grapes is a nice gesture: the NHS advises that fruit makes a good gift for convalescing patients.

About the author

Alice White

Alice is a digital editor and Wikimedian for Wellcome Collection. Before joining Wellcome, she researched frogs, moustaches, psychiatry in World War II, and British science-fiction fans.