Absinthe has a mixed reputation. From its role as a supposed cure for ringworm to inducing madness, David Jesudason charts how the controversial spirit made from wormwood, anise and fennel has both healed and harmed.

The trouble with absinthe

Words by David Jesudason

- In pictures

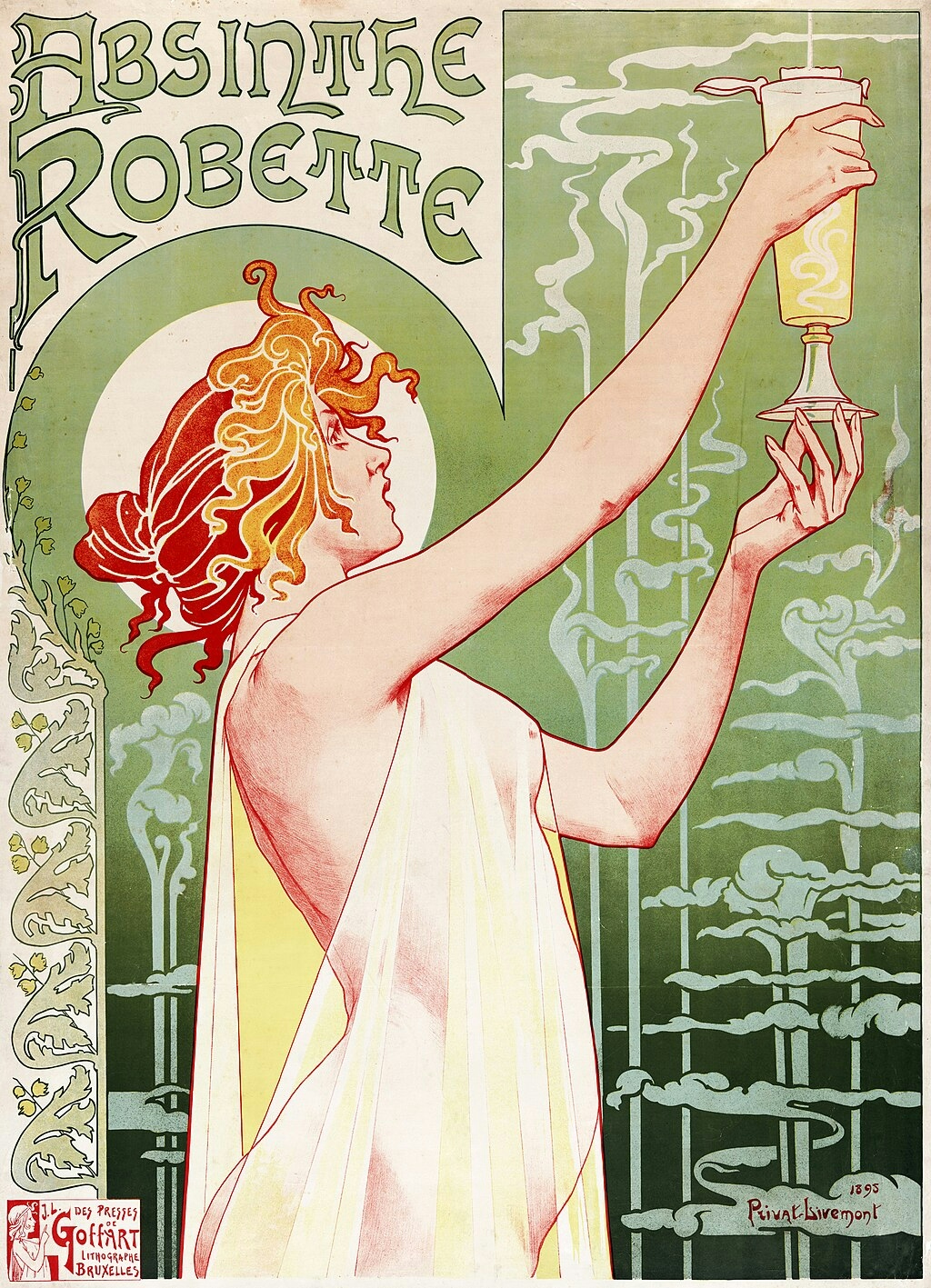

With its distinctive green colour and high alcohol content, absinthe is a spirit that has fuelled imaginations and controversy. Its high proof leads people to believe it’s dangerous, and it has become infamous for getting drinkers into trouble. Absinthe is often described as tasting of liquorice, which overlooks its subtle complexity: its flavours usually include fennel, star anise, herbs (such as coriander) and other botanicals. It’s fallen in and out of favour – and variously been banned – but can still be found on contemporary cocktail menus. The Absinthe Parlour in east London invites drinkers to try an avant-garde elixir “notoriously favoured by the rebellious minds of art and literature”.

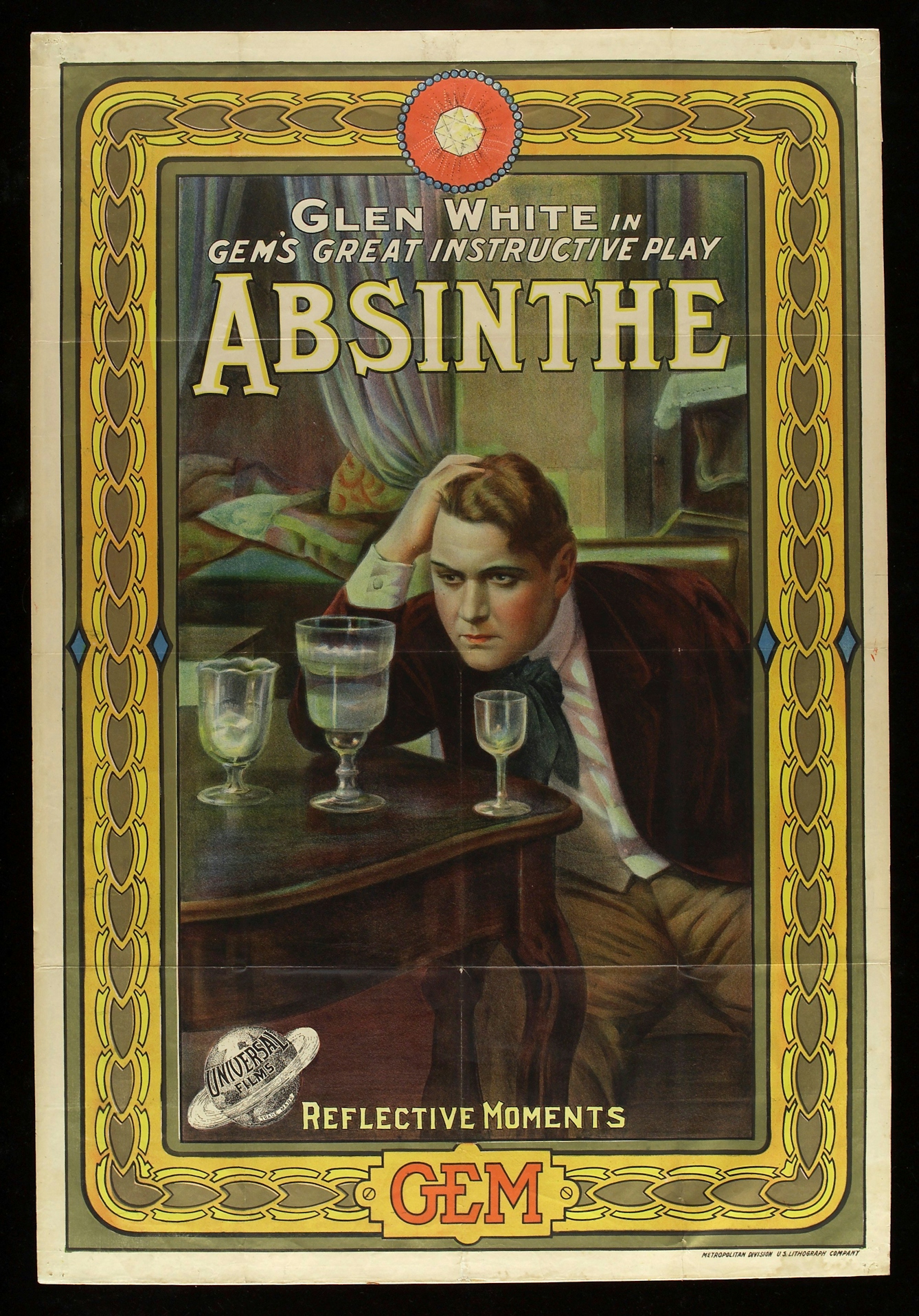

Is absinthe’s notoriety justified? Maybe we should look at the case of Frenchman Jean Lanfray to make up our minds. On 28 August 1906, he shot his pregnant wife in Switzerland after a drunken binge, which was dubbed “a classic case of absinthe madness”. Lanfray went on to murder his two daughters (aged four and two) before shooting himself in the jaw. But what’s often forgotten is he had also drunk six glasses of cognac, two coffees with brandy and two crème de menthes before his two glasses of absinthe.

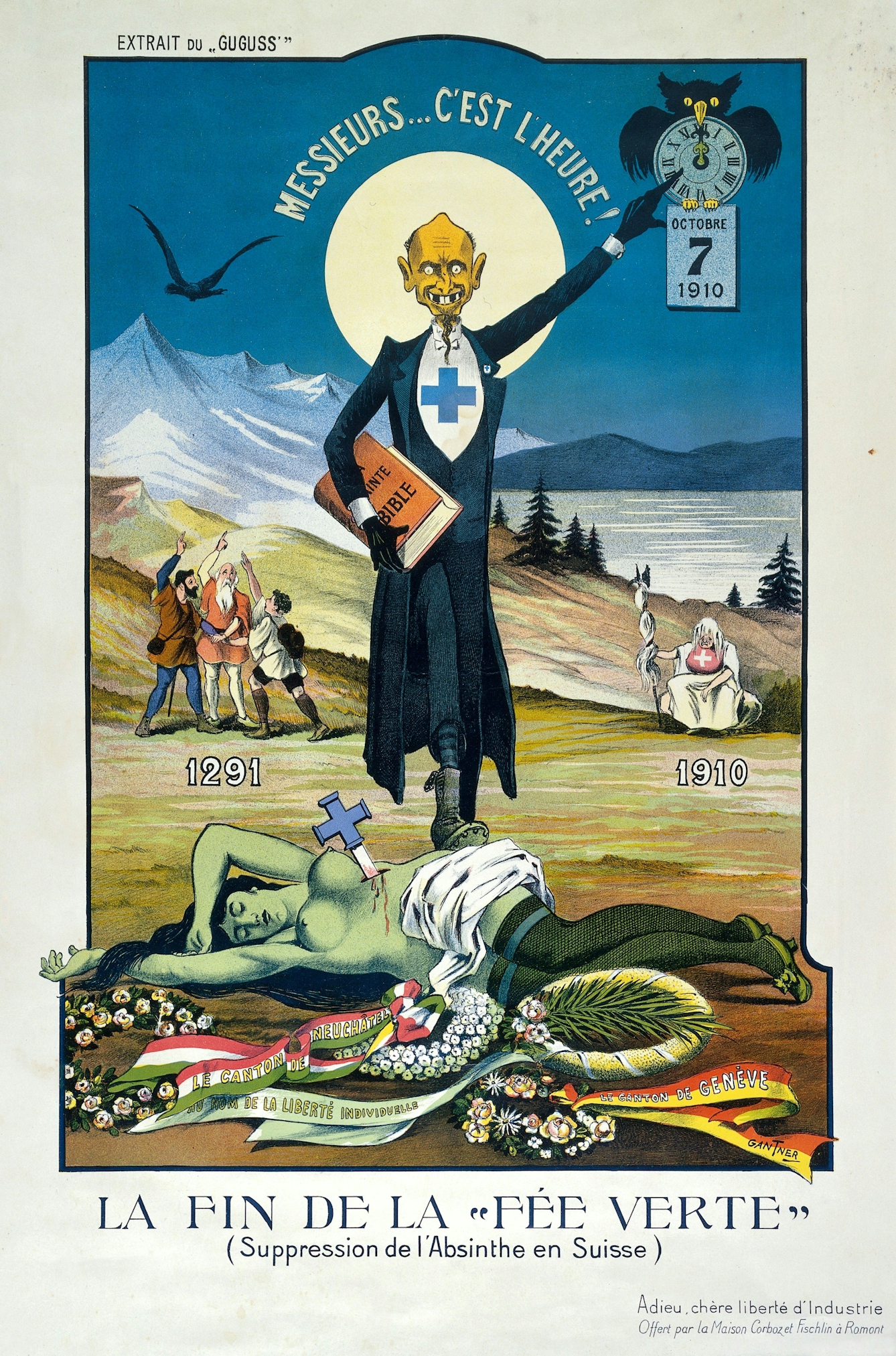

After the Lanfray murders, petitions were signed across the world calling for absinthe to be banned. Switzerland was the first to ban it in 1908. The US soon followed, making it the first alcoholic drink to be singled out there for prohibition. It would have come as a surprise to the French artist Édouard Manet, who had helped popularise the drink in Paris in the previous century. That said, Manet’s ‘Absinthe Drinker’ (pictured) was not met with widespread acclaim when it was displayed in the 1850s. His former master, Thomas Couture, believed his protégé had lost his “moral sense” by depicting such a squalid scene.

Absinthe had been popularised in London during the same period by another French artist, Edgar Degas. His painting ‘L’Absinthe’ gained notoriety for its realist depiction of degradation and moral decay, and shocked Victorian Britain. But, ironically, one of absinthe’s ingredients is life-enhancing: the wormwood plant (Artemisia absinthium) is said to help with digestion, pain management and the reduction of swelling. Wormwood got its name because it was used historically to treat parasitical worms, and wormwood drinks were seen as medicinal until the nearest relation to modern-day absinthe was patented by French doctor Pierre Ordinaire in the late 18th century.

Absinthe came to be prescribed for gout, dropsy and even for those working in hot conditions, such as bakers and glassblowers. It was also used by colonialists, with wormwood supposedly quelling fevers, preventing dysentery and warding off insects. Invading French troops in Algeria used absinthe as a cure for ringworm, mixing it with wine to give it more of a kick and curb some of its bitterness.

Absinthe was used medicinally by European invaders with white supremacist views, which was inconvenient for fellow racists, who had concocted a conspiracy about Jewish people and absinthe. French antisemitic author Edouard Drumont claimed that absinthe was a nefarious “tool of the Jews” because Arthur and Edmond Veil-Picard (who had purchased a stake in Pernod, a commercial absinthe producer) were half-Jewish. The only time Drumont showed any self-awareness was when he wrote: “I feel my heart more capable of hatred than of love.”

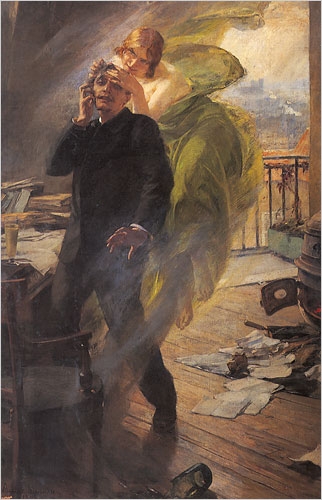

By 1880, absinthe had become known in French slang as “une correspondence”, which was short for “une correspondence pour Charenton”, which translates as “a ticket to Charenton”, an asylum on the outskirts of Paris. This was because absinthe was thought to cause harrowing hallucinations – the famous “green fairies” which were said to appear to some drinkers. These visions were most likely caused by the drink’s poisonous adulterants, such as impure alcohol and the colouring used to keep it bright green.

Absinthe had been banned during the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71) and the Pernod factory at Pontarlier, near the Swiss border, turned into a field hospital. Many in France blamed absinthe for their defeat in this conflict and for “the poisoning of the population”. Despite this, by 1910 France was thought to be consuming about 9.5 million gallons of absinthe every year. During the First World War, absinthe got the blame for enlisted soldiers’ poor health. It was once again banned in France in 1915.

Absinthe continued to be made in some parts of the world, including Eastern Europe, but most countries didn’t start lifting their bans until the 1990s. Absinthe’s demonisation had particularly suited winemakers in France. Then, in 2001, Kylie played the Green Fairy in the Baz Luhrmann film ‘Moulin Rouge’, appearing when a young poet and his bohemian friends drink a glass of absinthe. Twenty years later, absinthe is being distilled in Scotland and London. It was once believed to be a devilish brew, but many drinkers today seem to find it heavenly.

About the author

David Jesudason

David Jesudason is a freelance journalist who covers race issues for BBC Culture, Pellicle and Vittles. He was named Beer Writer of the Year in 2023, after his first book ‘Desi Pubs, A Guide to British-Indian Pubs, Food and Culture’ was hailed as “the most important volume on pubs in 50 years”. David also writes ‘Pub Episodes of My Life’, a weekly newsletter about the drinking establishments that serve marginalised people.