We often talk about how well we are working, of feeling sick of work or even of being worked to death. As Eoin O’Cearnaigh explains, while such comments are not generally meant literally, they still point to a complex relationship between health and work.

Working well or sick of work?

Words by Eoin O’Cearnaigh

- In pictures

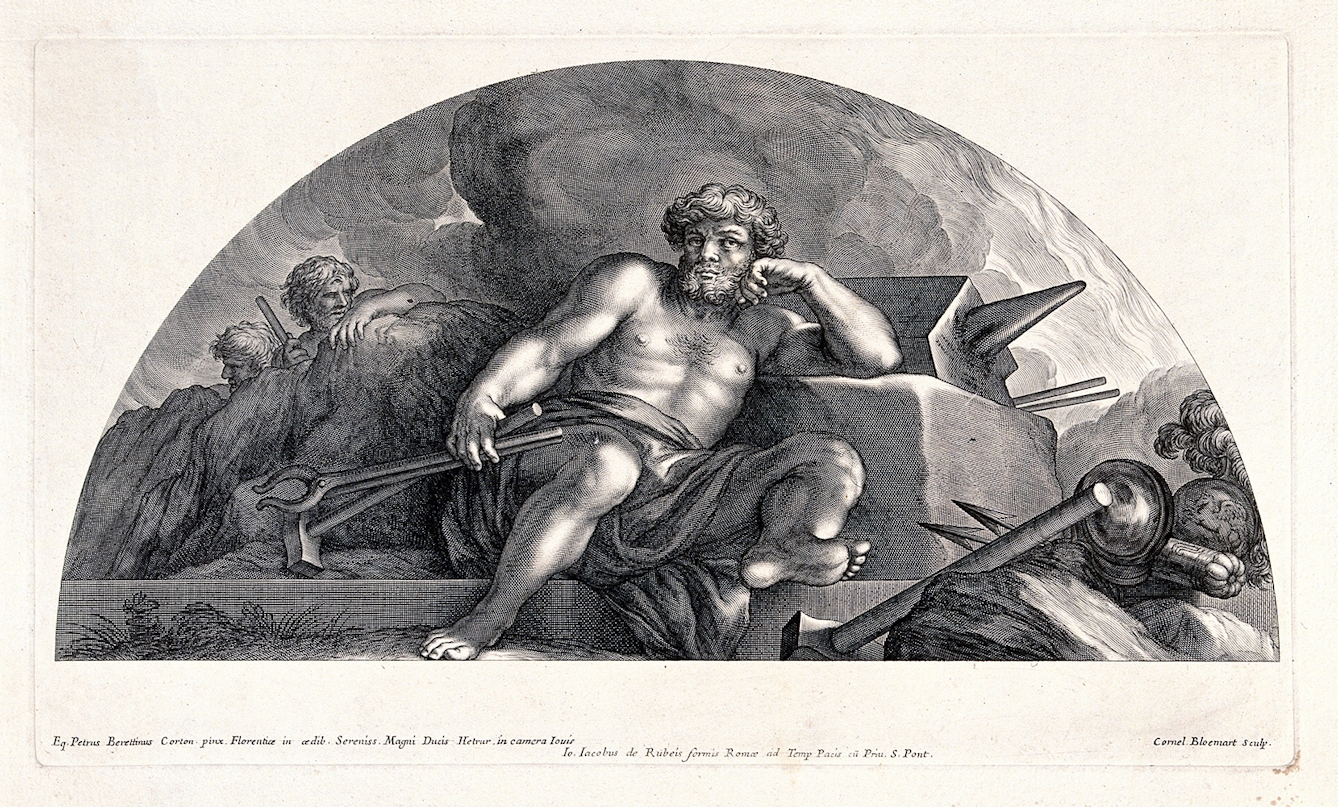

The ancient Greek god of blacksmiths, Hephaestus – or Vulcan, as the Romans knew him – was often shown with his anvil and tools. He was also traditionally depicted as having a physical disability. Archaeological evidence shows that Bronze Age metalworkers were exposed to the highly toxic heavy metal arsenic. Representing Hephaestus as disabled may have represented the symptoms that ancient metalworkers suffered.

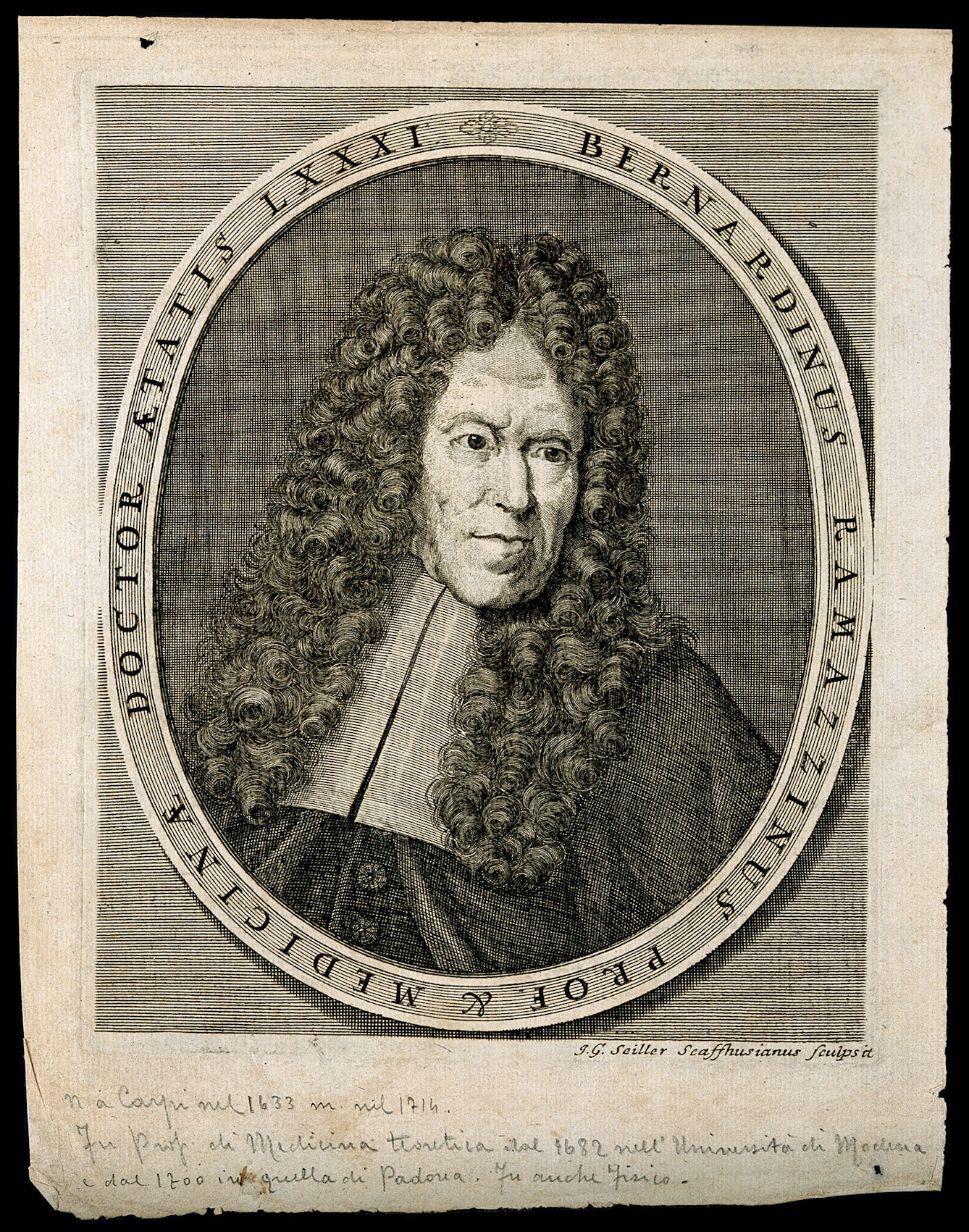

The first comprehensive study of occupational health was written by the Italian physician Bernardino Ramazzini in 1700. His book ‘Diseases of Workers’ was written after his experience of treating employees in the workshops of the Italian city Modena. Alongside trades such as glass workers, potters and painters, the first edition also featured men of learning.

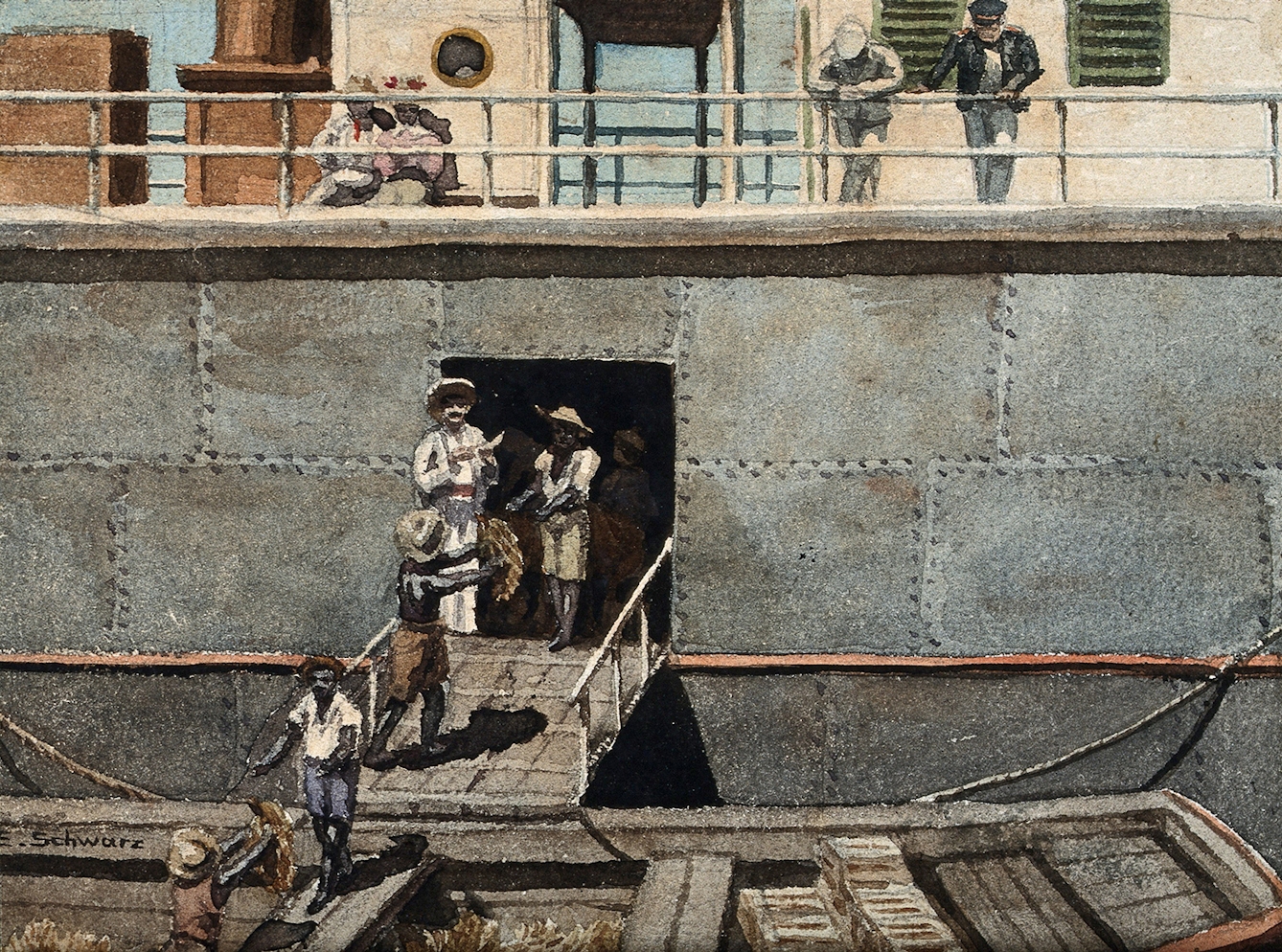

The slave trade used medical knowledge of the time to justify the transportation of Africans to the Americas. A key aspect of medicalising blackness was doctors’ argument that Africans were immune to yellow fever, which meant that Black people were put to work where the fever was endemic. This continued long after slavery was abolished, as shown in this 20th-century painting of Afro-Caribbean workers loading bananas onto a ship as white supervisors watch from a distance. Lettering explains that “infected stegomyiae [yellow-fever mosquitoes] may be introduced with the bunches of fruit”.

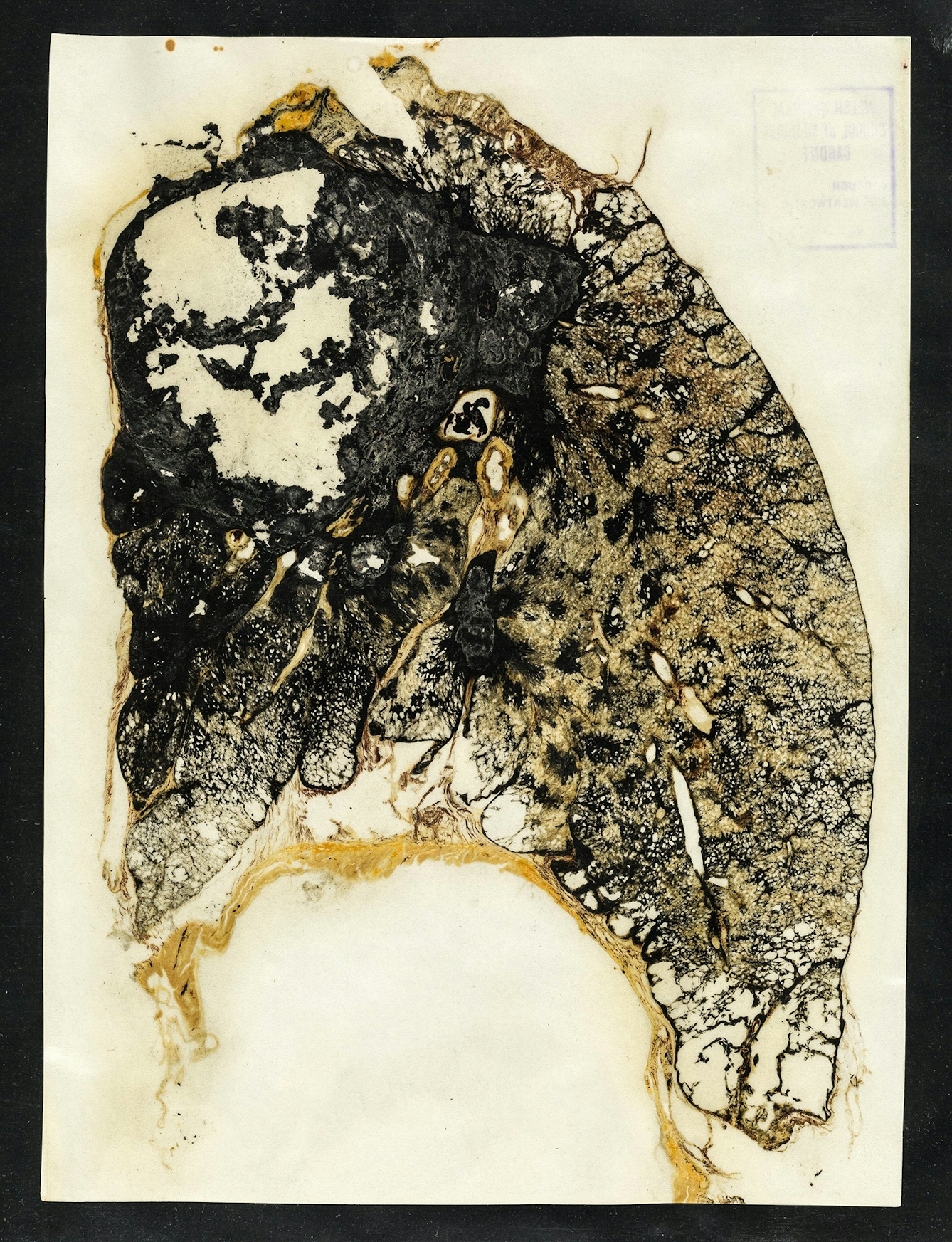

The risks of working in the mining industry have been known for a long time. The American Professor H A Lemen wrote the first paper on coal workers’ pneumoconiosis, also known as ‘black lung’, in 1881. He used the fluid coughed up by one of his patients as ink. It still took until the 1970s for US miners and their supporters to finally secure federal compensation and protective legislation against the disease.

Despite the risks of many kinds of work, work itself has also been endowed with healing properties. At Auguste Rollier’s clinics in Leysin, Switzerland, patients recuperating from tuberculosis were encouraged to spend time in the workshops. Although the development of occupational therapy was bound up with a variety of disputed assumptions about the inherent value of work, healthcare professionals today still recognise the benefits of treatments involving meaningful activity.

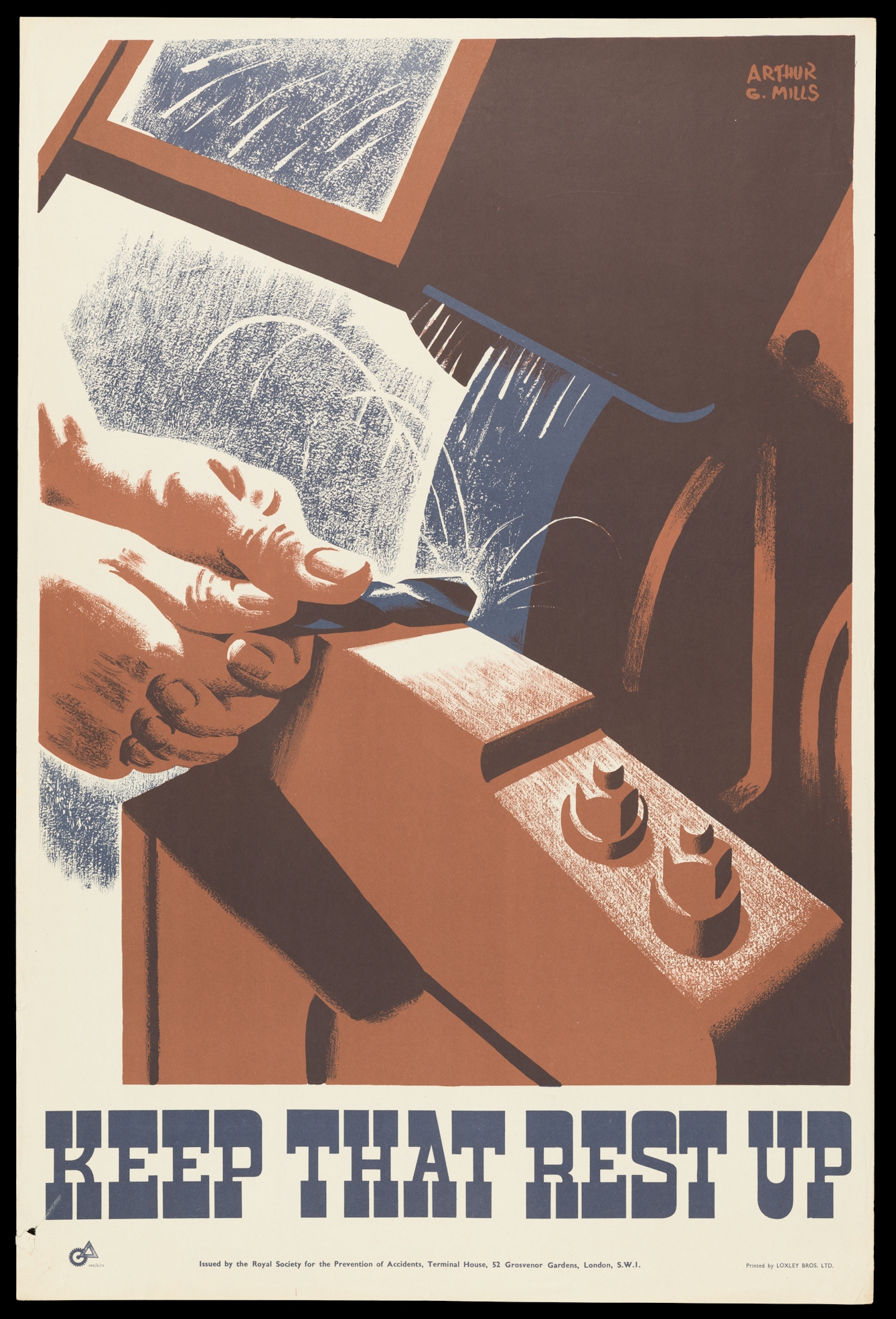

One of our main health and safety organisations, the Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents (RoSPA) initially emerged in the 1910s in response to an increase in traffic accidents caused by the growing number of cars on the road. RoSPA went on to campaign on workplace safety too, conveying their messages with eye-catching posters produced using modern graphic-design techniques. Health and safety became an important tool for challenging dangerous working conditions in the late 20th century.

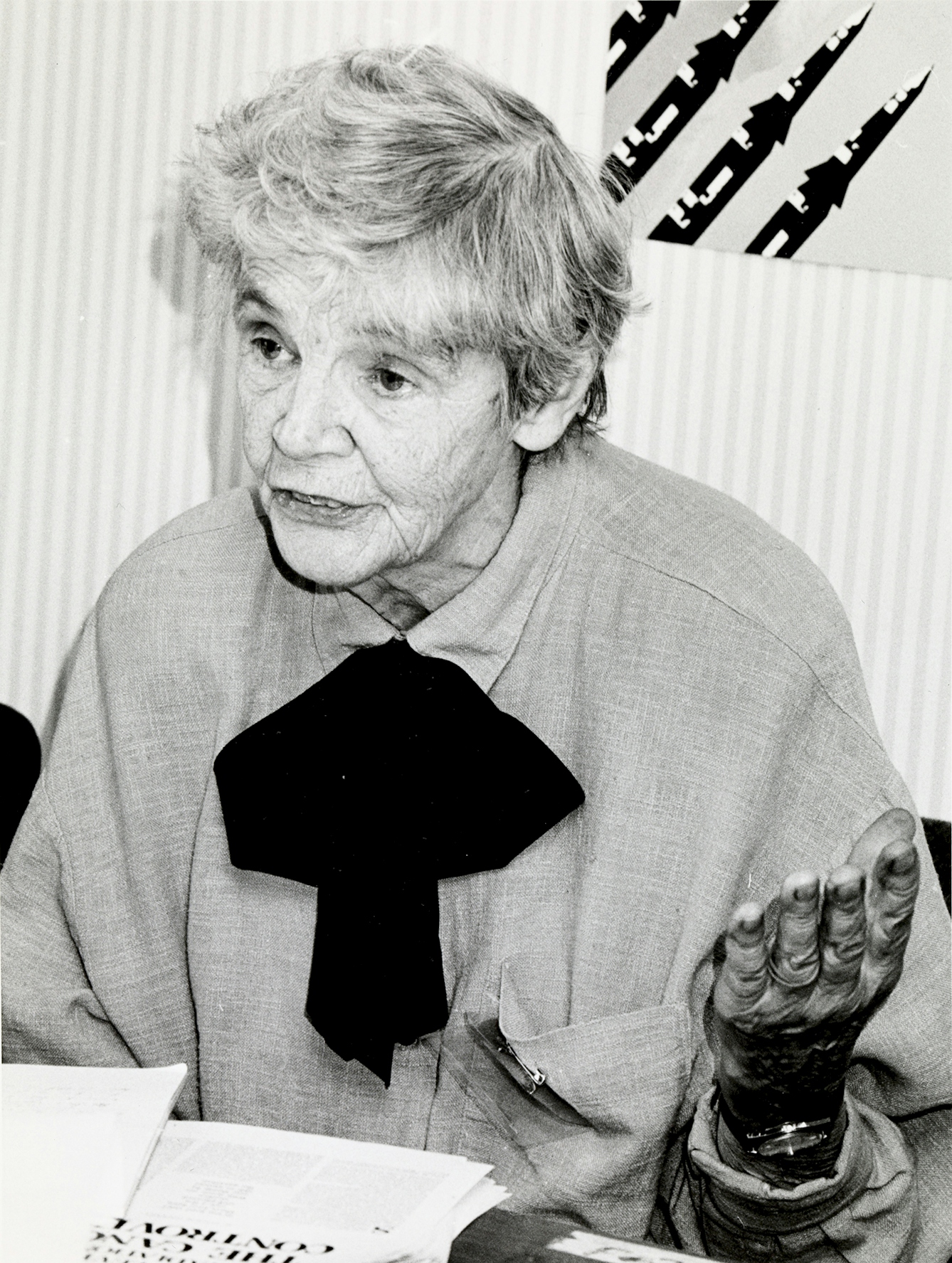

Occupational health increasingly used medical research to reveal the dangers of certain forms of work. The pioneering epidemiologist Dr Alice Stewart demonstrated the risks associated with exposure to low-dose radiation for workers in the nuclear industry. She also highlighted the risk to the foetus caused by routine X-rays of women during pregnancy, as well as to the radiographers who X-rayed them. Despite these achievements, her career was hindered because she drew attention to nuclear hazards at the height of the Cold War.

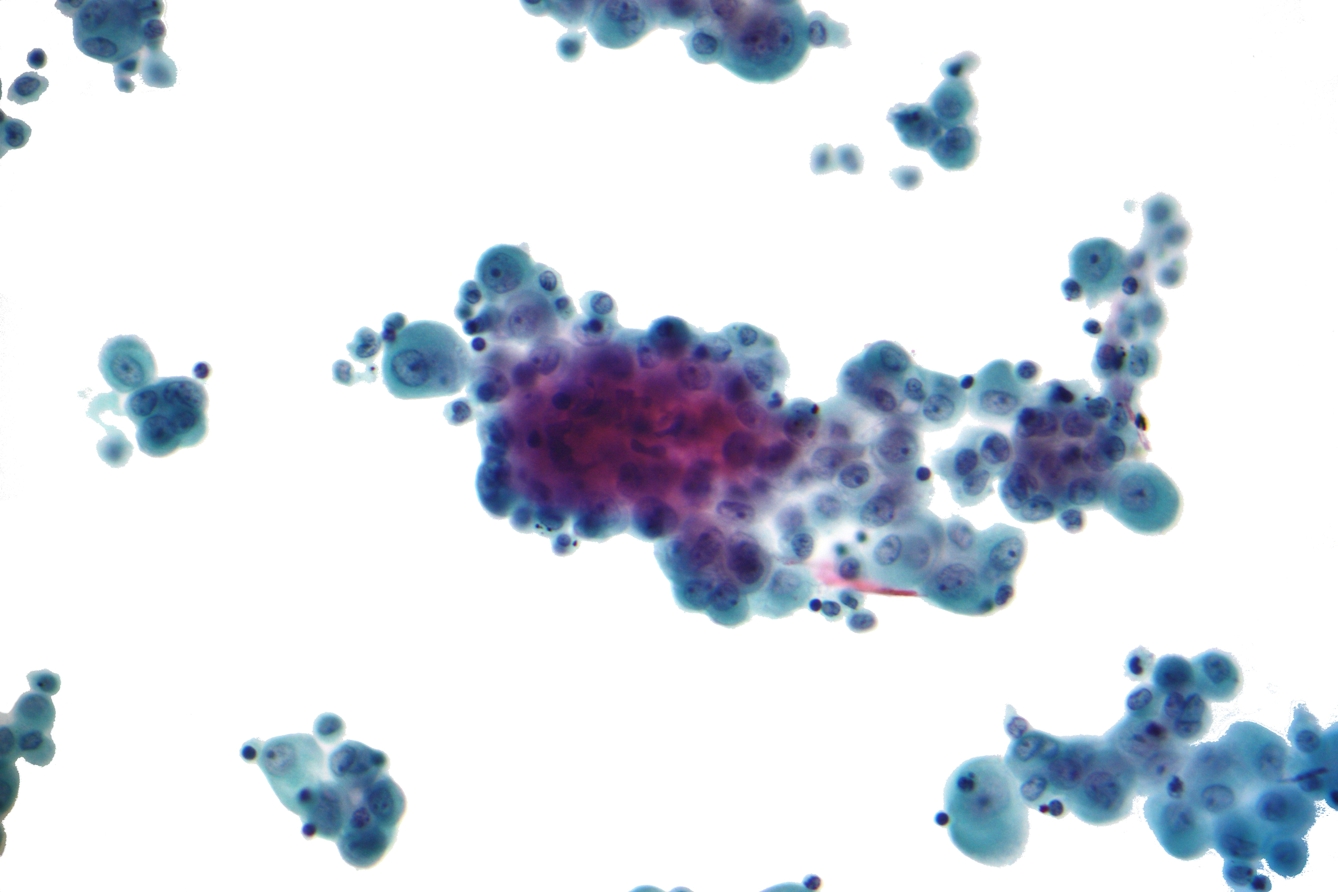

Major health issues remain linked to the world of work today. This microscope image of fluid from a patient’s lung shows signs of mesothelioma, a form of cancer associated with inhaling asbestos dust. While the exposure of workers in Britain to asbestos was at its height between the 1950s and the 1970s, a time lag before symptoms appear means that deaths from the disease have only peaked now.

About the author

Eoin O’Cearnaigh

Eoin is a research development specialist for Collections and Research at Wellcome Collection.