Report of the Commission appointed to Inquire into the Decrease of the Native Population, with appendices.

- Fiji. Commission appointed to Inquire into the Decrease of the Native Population.

- Date:

- 1896

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Report of the Commission appointed to Inquire into the Decrease of the Native Population, with appendices. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Library & Archives Service. The original may be consulted at London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Library & Archives Service.

296/442 (page 18)

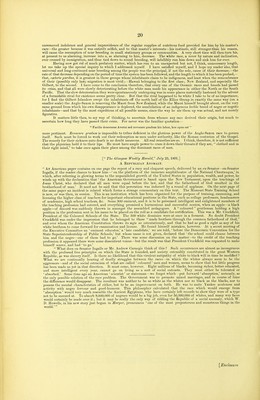

![work wonders ; will sometimes restore the lost vitality to such a degree as to enable us to continue the process of evolution (brought to a stand-still for want of it), on the same lines and in the same manner as before. A breeder, therefore, when required to solve the Pacific Population Problem, would inquire—■ 1st—On what system were thej' bred ? 2nd—How were they, and how are they fed ? 3rd—Are they possessed of sufficient versatility to derive benefit rather than take harm from the changes they have undergone formerly or are encountering now ? Having ascertained these particulars he proceeds to determine whether any important rule in the application of them has been violated ; and if such be the case, he can at once put his finger on the cause of the mischief. Let me now in this light review the facts connected with the inquiry I have undertaken. I find then that on every island in every group of Oceanica where any sort of reliable census is possible, the coloured population is found to be steadily decreasing. I thin]£ that, with the exception of the Gilbert Group, I am justified in assuming that where no census is possible, other data point to the fact that the same is the case. Further, that though greater in some places than in others, the difference is not important anywhere, while everywhere the evil is absolutelj' disastrous. Some of the natives seem to have become aware of their perilous condition ; but as that apprehension was roughly contemporaneous witli the intrusion of the white man among them—to that intrusion they have naturally enough ascribed the evil, which they then for the first time became aware of. Many inquirers have accepted their view of the case ; some going so far as to hold that there is a mysterious malign influence surrounding the white man like a poisonous atmosphere, which stifles every coloured race encountering it. I think this view is manifestly wrong. I believe it can be conclusively shown that the decrease is not materially, if, indeed, any greater in islands where the white population bears a large proportion to the colovu-ed, than it is in those where that proportion is infinitesimal. I am pretty certain for instance, from personal observation, that in the Marshall Group, where there are only a few traders, it is quite equal to that found in Fiji where the whites form quite an appreciable percentage of the whole population. Again, statistics show us that the negro who cannot in his own country hold his own against the manifestly (?) poisonous white man, is, in the United States where, in a decided minority, and of course subjected to all the supposed evils of white contact, we would expect his speedy extinction, nevertheless, increasing so fast as to utterly outstrip, in this particular, the destroyer (?) liimself. Here I cannot refrain from quoting some expression on this point printed by Governor Eyre in 1845, referring to the Australians. Year by year, he says, the melancholy and appalling ti'uth is only the more apparent; and as each multiplies upon us it becomes too fatally confirmed, until at last we are almost, in spite of ourselves, forced to the conviction that the first appearance of the white man in any new country sounds the funeral knell of the children of the soil. Mr. Moffat, at about the same date, and sj^eaking of the African Bushmen, says : I have traversed those regions in which, according to the farmers, thousands once dwelt, but now alas ! scarcely a family is to be seen. It is impossible to look over those now uninhabited plains and mountain glens withovit feelings of the deepest melancholy. The Bushmen referred to by Mr. Moffat, a missionary of the highest standing, only second to Livingstone himself, are, if not absolutely negroes, near enough that breed to justify me in assei-ting that what woidd or has affected the one would or has equally affected the other, and that either for good or evil. Let then any one wlio asserts the evil infl.uence of the white man per se fairly face the facts of the case, which are undoubtedly these,—that while the negro breed in question is rapidly fading away before him in the Cape Colony, in Natal, and the Transvaal, it is in its turn threatening to as effectually oust him from Louisiana, Alabama, and Texas. Armed with these pregnant facts I sav, emphatically, no connection between white contact, qua contact, can be made out; and further, that neither European disease, European vice, clothes, food, firearms, prostitution, fceticide, monogamy, rum, nor true religion, either separately or all together, all of which have been warmly upheld by various persons as undoubted factors in the evil, do really effect it in the least. For while the difference between the jiresent state of these two breeds of negroes is enormous, I do not believe that between an average Cape colonist and an average American planter to be appreciable. Furthermore I hold it only reasonable to think that the obliteration of the negro, which is attributed to his contact with white men on the soil of Africa, was very much more likely to overtake him in America, if we are to accept the theory as correct, and, therefore, I say, and still more emphatically than before, that the reason of the rapid increase of the one branch of the family, while the other is as rapidly dying out, is not to be sought for in any outside influence at all, but depends entirely and solely on a difference produced between them by the different manner in which they have been bred and fed; that different manner arising from the fact that the American master bred and fed his slave with better judgment and more according to rule than the free African bred and fed himself. The latter following too closely the vicious in-bred system forced on him by his situation, his feeling, and ancestral customs; the former practising that which has evolved Lady Suffolk, Dexter, Maude S, Bay Middleton, Flying Dutchman, and Stockwell, out of the horse which carried a jiack from York to London for our ancestors. In American hands, the African negro has become the longest-lived, almost the strongest, and far away the most prolific man we know; and if he only acquires the mental qualities of courage, pugnacity, and endurance which theoretically he is likely to acquire, then I fancy our cousin will find to his cost that out of the sickly and dying elements put into his hands he has managed to construct a Frankenstein, who will very shortly give him much more trouble and anxiety than he at all bargained for. With that trouble and anxiety we have happily nothing to do, but with the way it has been brought about much. The American planter, man-breeder if you will, has already, unconsciously perhaps, revealed the cause which I proposed to search for in this article ; and the outcome of his successfully aj)plied remedy seems to encourage us to go and do likewise. His hete noire his Frankenstein—could we only create his Oceanic counterpart—is just the man to repopulate the Pacific. Let me, therefore, endeavour to trace the man-breeder's method—noting with what he began, how he proceeded, how ended ; what difficulties he met, and how he met them ; where he was successful and where he failed. Then when we are more or less conversant with the history of the case, let us endeavour to see how far and with what chance of success it can be applied by us to the inhabitants of Oceanica, and more particularly to those of Fiji. Before proceeding to do this, however, it seems to me needful to clearly define the terminology of which I am about to make use—and this for two reasons. The first is, that breeding having been hitherto conducted by men as a ride, more ]5ractical than scientific, it has not as yet acquired concise terms for many of its processes ; secondly, the vague terminology which has acquired an uncertain recognition from breeders is ])artly unknown to me. I will therefore set down here the various terms of which I intend to make use, with the exact meaning I attach to each, premising that many are entirely empirical, and none of any value in their restricted sense beyond this pamphlet. A qualification Is any property of the mind or body possessed or acquired, by which development is facilitated. Potver Is a qualification of the body. Virtue Is a qualification of the mind. A disability Is a property possessed or acquired, by which development is retarded. Weakness Is a disability of the body. Vice Is a disability of the mind. To evolve Is to produce new properties. To develop To evolve new qualifications. To deteriorate Is to evolve new disabilities. A Characteristic](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b24399401_0296.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)