Genetics of resistance to bacterial and parasitic infection / edited by D. Wakelin and J.M. Blackwell.

- Date:

- 1988

Licence: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

Credit: Genetics of resistance to bacterial and parasitic infection / edited by D. Wakelin and J.M. Blackwell. Source: Wellcome Collection.

254/308 (page 240)

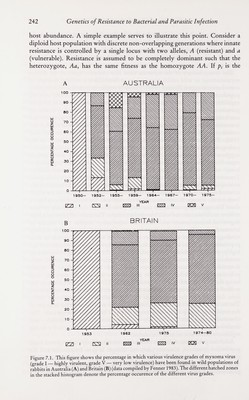

![240 Genetics of Resistance to Bacterial and Parasitic Infection hosts. An example is provided by the simple model of the population dynamics of a directly transmitted microparasitic infection defined in equations (1) - (3). There exists a critical host density [Xj, see equation (4)] below which the pathogen is unable to persist within the population. As such, the infectious disease will exert a selective pressure if host density is above this critical level but will have no impact on the fitness of resistant and vulnerable genotypes if host density lies below the threshold value. Early studies of frequency-dependent selection in host-pathogen interactions make the assumption that considerations other than the pathogen under study ultimately determine the magnitude of the host population (Hamilton 1980). Recent studies, however, have begun to address the question of how frequency- and density-dependent selection processes interact in associations in which the parasite influences the numerical abundance of its host (May and Anderson 1983). Such studies attempt to combine theories in population dynamics with theories in population genetics, but the resultant models are complex in structure and present many problems for analysis and interpretation. However, despite these problems, a number of generalities emerge. First, and most importantly, polymorphism is unlikely if a host genotype can evolve resistance with no associated fitness cost. Even when resistance carries some cost, it can be that resistant and vulnerable genotypes coexist, or that one always excludes the other, or that either genotype can 'win' depending on their relative densities (initial conditions) when either the resistant or vulnerable gene is introduced into the population. The outcome depends critically on the trade-offs between transmissibility and virulence of the parasite in the different genotypes. This issue is of direct relevance to the widely accepted view that 'successful' or 'well adapted' parasites evolve to be harmless to their hosts, and are, therefore, unlikely to exert any regulatory influence on host abundance or affect the genetic constitution of the host population. Theory contradicts this dogma and suggests that many coevolutionary paths are possible, depending on the relation between virulence and transmissibility of the parasite (Anderson and May 1982). Support for these theoretical predictions is provided by our current understanding of the sophistication and complexity of the vertebrate immune system. It is difficult to believe that such sophistication would have evolved, and been maintained, if parasites were and are not of major importance to the fitness of the host. Population geneticists, in contrast to parasitologists and ecologists, have held this view for some time (Haldane 1949). When confronted by the sophistication and hostility of the host's immune system, the parasite is constantly battling to survive. In this fight, the ability to multiply rapidly within the host and produce large numbers of transmission stages (both attributes are often directly correlated with the parasite's pathogenicity to the host) will often be beneficial to reproductive success even if the host is eventually killed by the virulent parasite. This is clearly the case if the host's immune system is able to suppress and eventually eliminate a slowly multiplying parasite, but is overwhelmed by the rapidly reproducing individual. The relationship between host and parasite will, therefore, coevolve in a very dynamic manner driven by the antagonism of the association. The life-style of](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b18032151_0255.JP2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)