Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: A text-book of pathology / by Alfred Stengel. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. The original may be consulted at the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh.

87/868

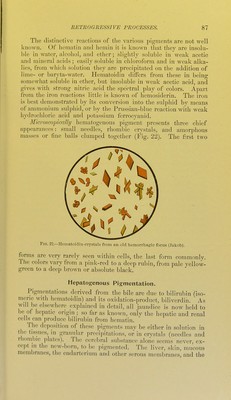

![following which it is deposited largely in the spleen, liver, intes- tinal mucosa, and kidneys. In these cases the mucous membranes from the lips downward may be more or less pigmented. Pigmentation through the alimentary ti-act is best illustrated by argyria following the excessive ingestion of soluble salts of silver. The depositions seem to consist of a reduced form of a silver albuminate. In the skin the pigment lies directly under the epithelial layer, between the cells, and in the intercellular tissue and lymph-spaces. The gastric and intestinal walls are deeply affected. The liver and kidneys are usually involved ; in the former the deposition is periportal, in the latter the glomeruli and the corticomedullaiy boundary contain the pigment; in both the cells are free. Among the rarer sites are the choroid plexus, the various glands of the body, and the walls of the blood-vessels. Pigmentation by cutaneous absorption apart from tattooing is problematical; it has been alleged to occur in workers in copper. Hematogenous Pigmentation. This concerns the deposition of pigments derived from the hemoglobin, of which there are two groups, the siderous and the non-siderous. The chief siderous pigment is hemosiderin, which has, however, many modifications; the non-siderous pigments are derivatives of hematin—hematoidin, hemofuscin, melanin, etc. In the course of time the siderous pigments may lose their iron. Probably all formation and further elaboration of these pigments are the result of specific cellular activities. T^vo groups of hema- togenous pigmentations may be distinguished, (1) those in which the hemolytic agents act in the circulating blood or the associated organs, and (2) those in Avhich the reductions occur in local tissues. _ 0) To the first group belong the general hemolyses. In per- nicious anemia and leukemia, in malaria, in severe cachexias, in occasional infectious and septic jn-ocesses, in poisonings (as by pyro- gallic acid, chlorates, arscniuretted hydrogen, by some mollusks, by pyridin and tuluylendiamin, etc.), the hemoglobin is set free in the circulation. It is i)romptly excreted by the kidneys, and to a hmited extent by the intestines; much is converted into bile in the liver, some little passing into the bile unchanged. A certain amount is reduced by the tissues (apparently by the liver) to the two before-mentioned series of pigments, which are then carried in the Jympliatic and vascular circulation and by means of cellular carriers and deposited in various ])laccs. As time passes, these pigments seem to become reduced, the iron being excreted by the intestine and the remainder by the kidneys as urobilin. In the •liver the depositions are largely in the perij)hery of tlie lobule; in the spleen, in the regions of the follicles; in the kidney the most marked collections are in and about the glomeruli and the tubules.](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21981668_0087.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)