Practical hydropathy : including plans of baths and remarks on diet, clothing, and habits of life / by John Smedley.

- Smedley, John.

- Date:

- 1861

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Practical hydropathy : including plans of baths and remarks on diet, clothing, and habits of life / by John Smedley. Source: Wellcome Collection.

450/530 (page 442)

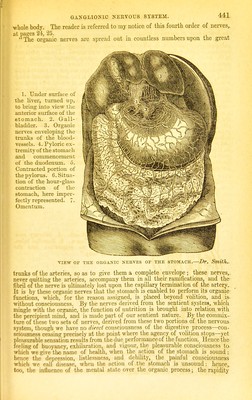

![and perfection with which the stomach works when the mind is happy when the repast is but the occasion and accompaniment of the feast of reason and the flow of soul • the slowness and imperfection with which the stomach works when the mind is harassed with care, struggling against adverse events or is in sorrow and without hope; when the friend that sat by our side, and with whom wc were wont to take, sweet counsel, is gone, and therefore 'one that which made it life to live. Renovation is the primary and essential office of the stomach, and its organic nerves enable it to supply the ever-recurring wants of the system. Gratification of appetite is a secondary and subordinate office of the stomach, and its sentient nerves enable it to produce the state of pleasurable consciousness when its organic function is duly performed. By the double office thus assigned it, the stomach is rendered what Mr. Hunter named it, the centre of sympathies.—Br. Smith The Muscles op the Body are the agents by which its different efforts'and movements are performed. In ordinary language they are known by the name •of flesiL _ Flesh is muscle. A muscle is a compound structure, made up of ■cellular tissue for its basis, which encloses it in its areole fibrine as the essential constituent. _ Tendinous fibres are superadded in most muscles, particularly at their extremities, forming the means of attachment to the perisotum and the bones. When we look at a muscle dissected, it evidently appears made up of fibres arranged in a defined direction; several of these are observed to be aggre- gated into bundles, each of which is detached from the rest by a thin lamilla of delicate cellular- tissue. Each bundle again admits of being separated into fibre, and these into fabrilla; and the separation may be continued until we at length -arrive at some so minute as to be incapable of further division. The muscles thus formed of bundles or groups of fibres, cither singly or in various combina- tions, draw upon the different parts of the skeleton to which they are attached, and put them in motion or steady and fix them as circumstances require. The skeleton of man contains more than two hundred separate pieces, and the muscles about two hundred and twenty pairs.—Quain and Wilson. Muscles. (Lardncr.)—The apparatus by which the bones are held together being described, it remains to show how those movements of which they are severally susceptible are imparted to them. The bones themselves are merely passive instrumentsand the ligaments by which they are connected, the form's given to them at the joints, the cartilaginous coatings, and synovial apparatus, are provided respectively for facilitating, but not at all for originating, their motions. The apparatus by which the motions are immediately produced are fibrous bands and masses of flesh called muscles, which constitute that part ot the animal body which when used for human food is called merit. With the visible fibrous structure of the muscular tissue every one must be familial-. Muscles consist of fibres ranged generally side by side, parallel to each other. They are extended between the bones, to one or both of which they are intended to impart motion; or, as in the face and eye, one end only is attached to bone. The muscle itself, however, is not immediately connected with the bone. At its extremities it gradually takes the form of tendinous fibres, totally different in their physical character from the fibres of the muscle itself. Tendons.—These tendinous fibres are sometimes collected into a single cord called a tendon, which is inserted in the bone so firmly that before it can be detached from it the bone itself would be broken.—Larduer. Muscular. ]foBCE.—Anatomists and physiologists have not determined with certainty the mechanical change by which muscular contraction is produced. When tlie muscular tissue is submitted to a microscope of moderate magnifying power, one, for example, of live or six times the linear dimensions, each fibre is found to consist of a number of fasciculi, each similar to the original fibre. The contractile power of the muscles which have been described can, in general, only be called into action by the dictate of the will. Hence thej are called voluntary muscles, and examples of them arc presented by the muscles](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b20398700_0450.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)