Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Outlines of zoology / by J. Arthur Thomson. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. The original may be consulted at the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh.

223/748 (page 185)

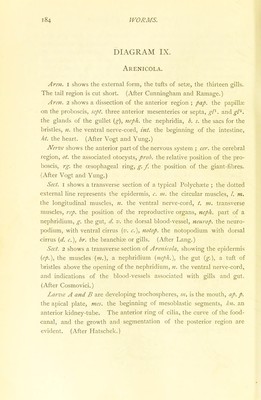

![General Survey of Chcctopoda. I. Oligochicla. Of Lumbricus there are many species, e.g., the common earthworm Z. terrestris, the dunghill worm L. fivtidus, and L. communis or trapezoides, whose ova usually form twins. We may conveniently include under the title earthworms a great array of animals more or less like Lumbricus, and usually described as terricolous Oligochceta. The senior student should make himself acquainted with the four groups—-Lumbricini, Geoscoi.ecini, Acanthodrilini, and Euurilini, and with the divergent branch MoNiUGASTRES, but it is enough for us to notice here that the modern classification is mainly based on the modifications of the excretory system. The largest earthworm is a Tasmanian species — MegascoUdcs gippslandicits—measuring alDout six feet in length, said to make a gurgling noise as it retreats underground. To these must then be added a number of families, Tubificidic, Enchytneidic, etc., which live in mud and water, and are often called limicolous Oligochreta. Of these a very common representative is the little river worm Tnbifcx ri7;uloruin, often found in the mud of brooks, and well suited in its transparency and small size for microscopic examination. Also notable is the fresh-water Nais, with remarkaljle powers of asexual budding. The advanced student should take note of the leech-like Branchiobdclla, which is parasitic on the crayfish, and apparently an abnormal Oligochtete. The two sets of which Liunbricus and Tubifcx are ty]3es, are united as Oligochceta, i.e., with few seta;, in contrast to the marine Chxtopods where the bristles are numerous, the Polychasta. II. Polychala. Living in surroundings usually very different from those of the more or less subterranean earth- and mud-worms, the marine Polychteta have richer development of external structures, and a more complex life- history. From the sides of the body-rings distinct outgrowths form the first genuine legs. These, known as parapodia, bear bundles of bristles, and are typically divisible into a firmer ventral neuropodium, often used for creeping, and a more leaf-like dorsal notopodium often respiratory. Special outgrowths of skin, on which lilood vessels are spread out, form the first genuine gills, and soft processes or cirri are present on some or all of the rings. The head is equipped with antenna.' and other tactile organs, and not unfref|uently with eyes, ear-sacs, and other sensitive structures. The sexes are usually separate, and the develop- rnent includes a metamorpliosis. the larval Irochospherc being (ptite different from the adult worm. (a) Some of these marine I'olycluvtes lead a free and more or less active life, crawling between tideniarks or on (he sea-bottom, burrr)wing in the sand, or swimming in the open water. These Errantia have well- developed appendages, and a large |)re-oral segment, and are generally furnished with eyes and well-(levclo])ed antennx. Gills are usually associated with the dorsal parts of the parapodia. Most of them feed on](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21958671_0223.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)