Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: A text-book of anatomy / edited by Frederic Henry Gerrish. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by The University of Leeds Library. The original may be consulted at The University of Leeds Library.

25/930 (page 19)

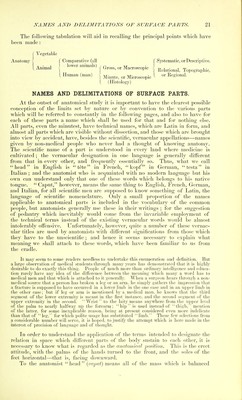

![anatomy also can be acquired in this way; but a very modern method has revealed a multitude of facts in this connection which were previously unknown, and are incapable of demonstration by dissection alone. This new method is that of plane sections. The sections are made in the following manner : a body is frozen so hard that a. saw, in cutting through it, encounters no more resistance in bone than in muscle. Cuts with a saw are made in any direction which one chooses, but the most common are the horizontal, the vertical sidewise (also called coronal or frontal), and the vertical fore-and-aft (known also as sagittal). The cut having been made, the saw-dust is very carefully cleared away from the surfaces, and the relations of the parts which have been brought to view are studied. As an elevation of temperature above the freezing-point will impair the fixity of the specimens, and as it is manifestly out of the question to maintain such a degree of cold permanently or to study the specimens com- fortably during its continuance, it is usual to photograph them, or immerse them in a preservative fluid in flat vessels covered with plain glass, or to adopt both of these devices for continuing the study. Students are not expected to do this work, which involves great labor, skill, and, for interpretation of the appear- ances of the sections, a high degree of anatomical knowledge ; but they can avail themselves of the results of this method by studying the actual sections or casts of them in their medical schools, or, what is sometimes better because more intel- ligible, pictures of sections made from photographs and labelled in detail. Minute or viieroscopic anatomy deals with those features of structure which are too small to be recognized by the unaided eye. It can be studied only with the assistance of a microscope. A branch of microscopic anatomy is histology (the name coming from the Greek word for textux'c), which is the science of the tissues. But the name histology has been much used synonymously for microscopic anatomy, the whole getting its designation from a part, as in many other cases in our language. Histology is sometimes called general anatomy, because the tissues are distributed to all parts—are general to the various organs. A homely illustration will serve to make the difference between these various subdivisions of anatf)my clear. We may use the word anatomy with refer- ence to artificial structures, as, for instance, the anatomy of a steam-engine or of a watch or of a house. Let us, then, regard a house from the points of view successively of the systematic anatomist, the topographic anatomist, and the histologist. The first of the trio considers the house as made up of sets of organs, a series of apartments devoted to alimentary purjioses, as the kitchen and dining-room ; another set used for sleeping—the Ijcd-chambcrs ; one for study—the library, and so on ; a system of tubes conveying water to various parts of the establishment ; another lot bearing illuminating gas to every room ; a third sujjplying steam or hot air for raising the temperature ; and still another carrying off liquid waste materials; large, vertical pipes by Avhich injurious products of combustion arc conducted away ; a quantity of wires adapted to the conveyance of electricity for various pur])oses within the house, and a set of rods designed to keep electricity out of it. Thus he finds whatever organs go to com- pose a house, and describes each set by itself, so that a person who desires to know about any system of apparatus—as, for example, that used for heating or that for sewerage—can learn about it by consulting the recoi'd of the investi- gator's observations. The topogra])hic anatomist approaches the question of the structure of the house in an entirely different way. He examines the building by such means that, without actually cutting it into slices, he is able to make drawings which show just what these plane sections would display if they were made. He does not concern himself with any separate system of rooms or rods or pipes or wires, but he studies the relations which obtain between all of the objects which he sees in each of his imaginary sections. For example, he observes that the parlor is related to the cellar below, to a bed-chamber above, to a library behind,](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21506620_0025.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)