Human genetics : minutes of evidence, Wednesday 8 February 1995 ... / Science and Technology Committee.

- Great Britain. Parliament. House of Commons. Select Committee on Science and Technology

- Date:

- [1995], ©1995

Licence: Open Government Licence

Credit: Human genetics : minutes of evidence, Wednesday 8 February 1995 ... / Science and Technology Committee. Source: Wellcome Collection.

15/40 (page 85)

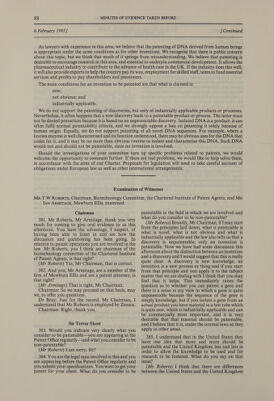

![8 February 1995] [Mr Batiste Cont] will be different from the one before it and the one after it. In looking at each individual case we have to have regard to practice round the world, what is being granted and what is not, the views of judges in particular in this country as to what should be granted and what should not be granted and to what Parliament says, so that you have in effect a circular system in this country and one which is global, and within that we try to slot each application in a moving situation where, as I said, 25 years ago you had one situation and today it is different and ten years hence it will be different again. Perhaps Derek Wood has something to add here. (Mr Wood) Mr Chairman, the measurement as far as we can do it is done against what is already known in that particular art itself. 357. If, for example, very sophisticated computer programmes are designed to try to eliminate alternatives and to come out with what the probable function of the gene is, quite clearly there may or may not be protections—if the programme is patented there would be and if it is not there would not be— and it may not in itself be directly patentable, but once that sort of programme is running the application of the programme itself would then eliminate the inventive element because there would be a known technology for discovering the function of a gene and once you have reached that point you would move forward and say that the mere discovery of the function of the gene would not be patentable. (Mr Hartnack) It might be worth bringing in one of the concepts of the patent which is that whatever the applicant is seeking a patent for must not be obvious to someone who is skilled in the art. Now clearly as science moves on more people become skilled in the art and therefore obviousness is the test in this area; so that what is obvious today was certainly not obvious in 1980. That is the judgment that the examiner has to make. Chairman 358. What would be the average life of a patent in this area? (Mr Hartnack) In this area, Mr Chairman, it depends on the amount of money that it is making. The system is about money. The average life of a patent is about 11.2-11.3 years. If they are making a lot of money they could last for 20 years; and if they were in the pharmaceutical area they might be eligible for a supplementary protection certificate. Dr Bray 359. Your limitation of consideration to what is of commercial and industrial interest, excluding the philosophical and moral considerations, is in danger of including also logic and equity. For example, you argued, Mr Wood, that the presence of introns in some way differentiated the gene under consideration from the gene as it is patented. It is rather like saying that the railway timetable which has got a fly stuck in the middle of it is different from a pristine railway timetable without the fly. Is that not totally irrelevant? (Mr Hartnack) What we are trying to do is to take account. It is our practice—it is the practice of all [Continued patent offices—to tend to err in favour of the applicant and we do that because, as I say, our function is to try to foster innovation. Now in erring in favour of the applicant we know that all of our decisions are challengeable in the courts. We also know that in almost any area of technology there will be competitors so if we were to err in favour of one pharmaceutical company in this country and the competitors of that company thought that we had gone too far, then they would challenge that decision in the courts; so indeed would other interests, people who— 360. Yes, but with respect an individual scientist on a £20,000 research programme who is grossly overspent already could not possibly afford to contest a patent filed by some pharmaceutical company which is knocking out his whole area of research. (Mr Hartnack) If that scientist worked for a university presumably he would be being funded by the Medical Research Council, and if the Medical Research Council felt that its ability to pursue fundamental research in this country was being prejudiced, then the Medical Research Council would take up the case and other interests would take up cases. 361. But you are really making it extremely difficult for us in wanting to provide the maximum possible incentive for the pharmaceutical industry to find effective applications of genetic concern to define their interest in such a way that it does not unduly limit the pursuit of the research phase. Do you not have an obligation also, not to the person who applies for the patent but the person who would otherwise use the information if it were not patented? (Mr Hartnack) That is not the way that Parliament has seen it hitherto, and I can only repeat that the basic mapping of the genome is largely funded by government in this country, so as far as the fundamental science is concerned government has taken that on precisely because it is, if I may use the term, blue skies science. What the Patent Office addresses itself to is science in this area where as of today we are not talking about genetic sequences of unknown utility. Therefore it is much more applied science and less likely. Chairman: For commercial purposes. Mr Batiste 362. You have already said that in your view things having developed to the point that they are now a gene of unknown utility is not patentable. Would it be possible subject to protection from the law of copyright? (Mr Hartnack) 1 have pondered that at great length. The difficulty is that even if it were —and the 1988 Act talked about copyright protection for tables or compilations so I suppose from that point of view it might be regarded as complementary, but that does not really help because no one would want actually to print copies of the genome and sell them to someone. You see the difficulty? Mr Batiste: Yes.](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b32230175_0015.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)