Europe after Maastricht : interim report : report, together with the Proceedings of Committee, Minutes of Evidence, and Appendices : first report [of the] Foreign Affairs Committee.

- Great Britain. Parliament. House of Commons. Foreign Affairs Committee.

- Date:

- 1992

Licence: Open Government Licence

Credit: Europe after Maastricht : interim report : report, together with the Proceedings of Committee, Minutes of Evidence, and Appendices : first report [of the] Foreign Affairs Committee. Source: Wellcome Collection.

77/96 (page 61)

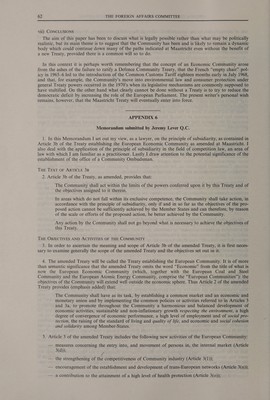

![tem of central banks) by the same method, although the existing case-law on delegation of powers sug- gests that it would not be possible to grant such a body power to issue binding Community legislation of the types defined in the Treaty. Similarly, if secondary legislation has already created the ECU, can it not further define its role as a currency? Such legal theorising should however be tempered by the need for economic convergence, as was realised by those who drafted the Maastricht Treaty. iv) SOCIAL POLICY The Maastricht Protocol on Social Policy does, of course, purport to allow eleven Member States to act together through the Community institutions. However, the present author is one of those who has doubts as to how far it would be used. It refers to continuing “along the path laid down in the 1989 Social Charter” (also signed by eleven Member States). That Charter declared expressly that its imple- mentation “must not entail an extension of the Community’s powers as defined by the Treaties”, and listed in detail the existing provisions which could be used. Legislation has in fact been issued under gen- eral Treaty powers which expressly states that it is intended to implement the Social Charter, such as Directive 91/533 on contracts of employment, which, since it was made under art.100 which requires una- nimity in the Council, must at the least not have been opposed by the United Kingdom minister. This pattern has been repeated in Council Directive 92/56 on collective redundancies. The present author remains of the opinion that most of the Social Policy Protocol may be achieved under existing Treaty provisions. Vv) OTHER POWERS The present writer has gone on record elsewhere with the view that most of the “new” powers in the Single European Act represented Treaty recognition of developments which had already taken place under general Treaty powers, in particular arts.100 and 235, in areas such as environmental law. The same approach could be taken with regard to the Maastricht Treaty: when it was signed there was already Community legislation on, for example, consumer protection, tourism, energy policy, European networks, health protection and (to a limited extent) education. Whilst many current EEC provisions may only be used to the extent “necessary” for the achievement of the Community’s objectives, failure to ratify the Maastricht Treaty will mean that there will be no express reference to subsidiarity. To some extent the political objective of requiring the Community leg- islative institutions to bear that consideration in mind would appear already to be being observed; for example, Council Decision 92/421 on tourism policy expressly refers in its recitals to the “need to comply with the subsidiarity principle”. On the other hand its legal effects may be doubted. In this context it is worth recalling the long-estab- lished case law on the the judicial review of a Community institution’s discretion. Where “the evaluation of a complex economic situation” is involved, the Court must confine itself to examining whether the exercise of the discretion contains a manifest error, or constitutes a misuse of power, or whether the insti- tution did not “clearly” exceed the bounds of its discretion!. Since this case-law was developed in the context of the exercise of delegated powers by the Commission, it would seem highly unlikely that the Court would wish to exercise a greater degree of control over the exercise of original legislative power by the Council of Ministers. vi) INSTITUTIONAL REFORMS What cannot be done without a treaty amendment, however, is to change the legislative procedure under which Community measures are adopted. Nevertheless, while it is in the institutional and procedu- ral area that the failure to ratify Maastricht would be most noticeable, certain provisions do no more than to consolidate the case-law of the European Court, notably the revised art. 173 of the EEC Treaty with regard to the status of the European Parliament as applicant and defendant in actions for annul- ment, and the reference to respect for fundamental rights “as general principles of Community law” in art.F(2) of the “Common Provisions”. On the other hand, it is difficult to see how reforms of legislative procedure, in particular the co-decision mechanism between the Parliament and the Council, can be introduced into existing areas of Community competence without a Treaty amendment agreed by all the Member States; indeed, while it may be possible for eleven Member states to operate new procedures agreed by them in new areas of competence which apply only to them, it may be submitted that a serious problem even with the Maastricht Protocol on Social Policy (if it comes into force) is the overlap of cer- tain of its substantive provisions with unrepealed provisions of the present version of the EEC Treaty. Finally, it may be observed that Protocols on such matters as the Irish constitution and the interpreta- tion of the European Court’s judgment in the Barber case will disappear if the Maastricht text does not enter into force. With regard to the latter Protocol, it may be wondered what effect it will have even if the Maastricht text does eventually enter into force if the European Court delivers another judgment tak- ing the matter further in the intervening period. ' Case 55/75 Balkan v. HZA Berlin-Packhof [1976] ECR 19 at p. 30.](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b32218977_0077.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)