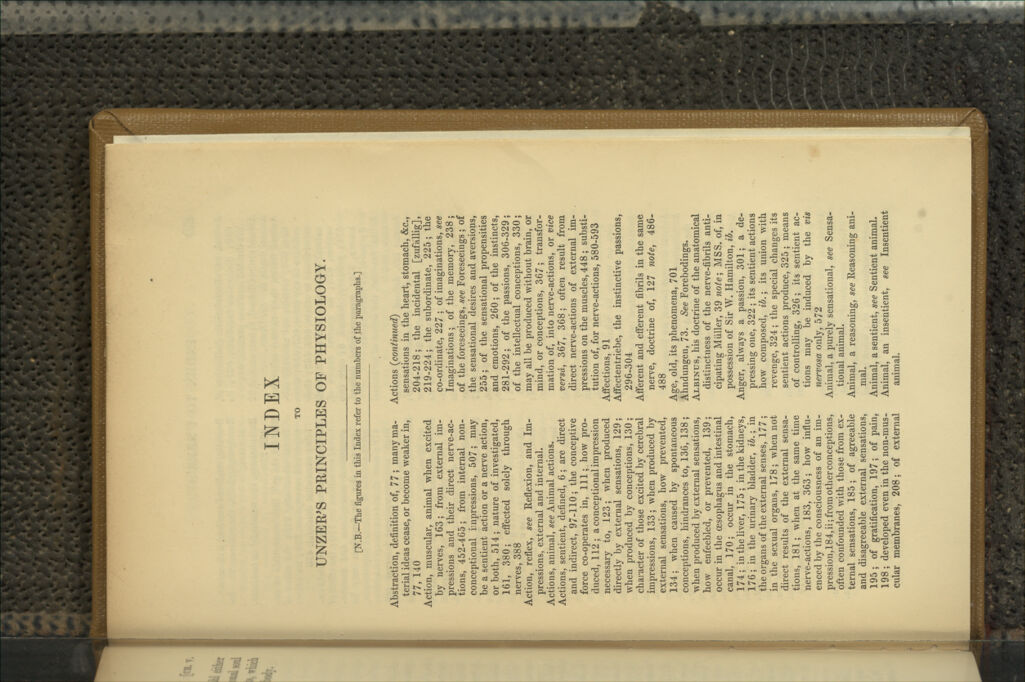

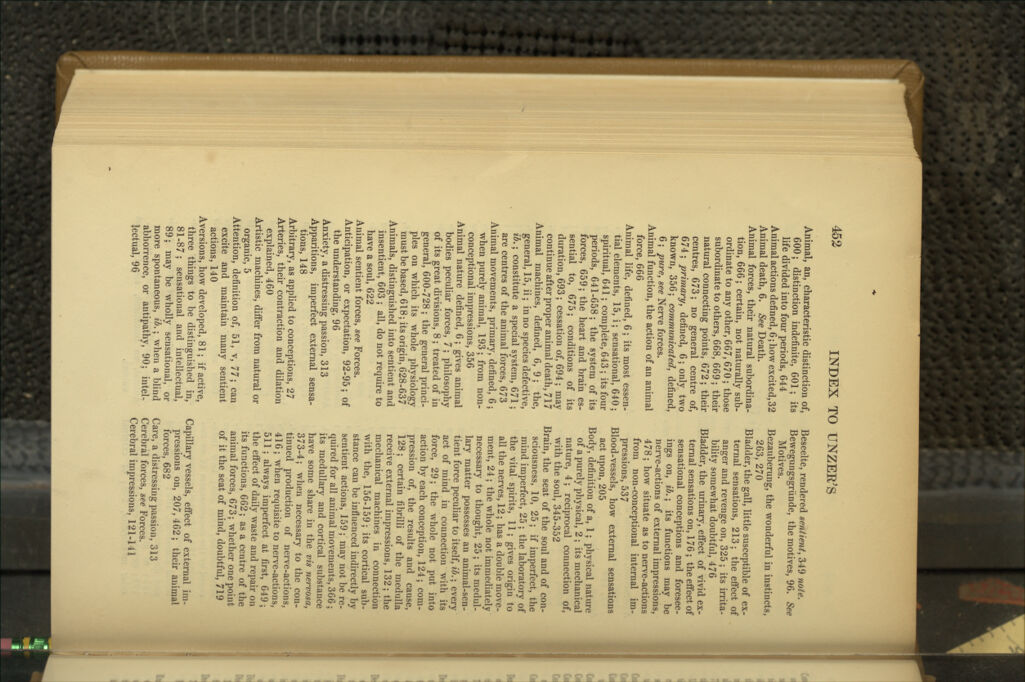

The principles of physiology by John Augustus Unzer; and A dissertation on the functions of the nervous system, by George Prochaska.

- Unzer, Johann August, 1727-1799.

- Date:

- 1851

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: The principles of physiology by John Augustus Unzer; and A dissertation on the functions of the nervous system, by George Prochaska. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by the Gerstein Science Information Centre at the University of Toronto, through the Medical Heritage Library. The original may be consulted at the Gerstein Science Information Centre, University of Toronto.

482/504 (page 448)

![some body applied to the nerves. Whence, therefore, it is manifest, that those movements ought alone to be termed animal which depend upon the untrammelled control of the soul, and which it produces or restrains by its own free will; on the other hand, those which in no degree depend on the will, but are performed when the mind is unconscious or un- willing, cannot be termed animal, but are purely mechanical and automatic. Observation teaches, that there are some muscles in the human body over which the mind has no control whatever, and the movements of which are purely automatic during the whole of Ufe; these are the heart [the ventricles], the auricles, oesophagus, stomach, and intestinal canal; with these may be mentioned the motion of the iris. There are other muscles which are ordinarily subject to the control of the will, and for this reason are termed voluntary, such as the muscles of the limbs, trunk, head, face, eyes, tongue, genitals, and the sphincter of the anus and urinary bladder. It sometimes happens, however, that all these muscles renounce the authority of the miud, and while it is either unconscious or unwilling, are violently agitated by some preternatural mechanical stimulus, as is seen in hysterical, epileptic, or infantile convulsions, or in those affected with St. Vitus^s dance; and these movements, although performed by muscles designated voluntary, can only be termed automatic. In the foetus in utero and in the newly- born these muscles are not moved voluntarily, but for the most part automatically, for at that age the cerebrum is not as yet capable of thought, until the organs of the faculty of thought being gradually evolved, the mind learns to think, and to use the muscles subjected to its control. The raising of the hand and the application of it to the head in apoplexy belong also to the class of automatic movements, also the turning of the body in sleep, and partly even somnambulism itself, which, however, it would seem is partly also to be ascribed to obscure sensations and vohtions which the mind instantly forgets. In the third place, there are muscles which continually act in- dependently of the will, being excited thereto by a mechanical stimulus only, but over which the mind possesses voluntary command, and can at will accelerate, or retard, or entirely stop their movements for a time; the action of these is termed](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b20995465_0482.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)